The minor mystery of ‘dolphin cheese.’

While conducting research about the foodways of Atlantic Canada, the Editor encountered a passage about the consumption of cheese in Quebec during the eighteenth century. It is from A Taste of History by Marc Lafrance and Yvon Desloges. The authors note that Quebec then imported a variety of cheeses from England, but not Cheddar until the end of the 1800s. They list the usual suspects like Cheshire and Stilton, but also more obscure varieties including Wiltshire, North Wilton and Dolphin.

Dolphin cheese was a mystery. Why the name, and where did (does?) it come from? The questions are not so easy to answer, although it was indeed an English product. Writing in 1745, William Ellis appears to place the product in “the Vale of Alesbury,” or Aylesbury, but it is not clear whether people made it anywhere else.

It may have been unique to the Vale because, although proving a negative is difficult, it apparently has not been described by anyone other than Ellis. That could make sense; Aylesbury, located in Buckinghamshire below the Chiltern Hills, has been long famous for its cattle, including “milch cows.” (Gibbs 662-65) Ellis found “plentiful crops… of Cheese” and other profitable commodities in there. (Ellis 22) According to a local nineteenth century author, “[t]he beeves here pastured reach gigantic proportions; the sheep are not excelled in any part of the world….” And Buckinghamshire itself produced more milk than any other county in England. (Gibbs 663)

By 1745 Dolphin cheese had become a curiosity. Ellis wrote that “of late Years it is much in disuse” and congratulates himself for introducing his reader to such a “Matter of Novelty.” (Ellis 98) No writer that we have encountered chronicles its revival.

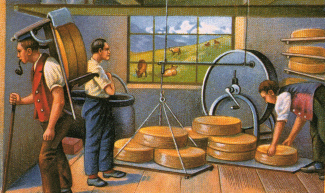

The Dolphin cheese that Ellis describes was anything but an export commodity. Instead, they were produced individually to celebrate the birth of a child in dairying communities, where the women made a special cheese for the occasion, decorated with the relief of a dolphin. The image resulted from

“a Cut of the Figure of a Dolphin-fish in the wooden Mould, wherin the Cheese is press’d, it receives the Impression of the Dolphin on only one side of the Cheese, in as full Proportion as the Length of it will admit; and that it may have the greatest Length, these Cheeses are generally made in a square Fashion…. ” (Ellis 97-98)

A Dolphin cheese was as much symbolic as practical, an item

“much esteemed as an Ornament, as well as a Service to a lying-in Woman’s Chamber, where the Gossips were wont to cut a Piece on the outside of the Dolphin’s Figure, in order to preserve the Sight of it to the last; for some would take a Pleasure to see this Figure so made on the Outside of the Cheese, with the very Scales of the Fish.” (Ellis 98)

Ellis reports that Dolphin cheese required more labor than conventional round cheeses. Because of its shape, the cheese had a greater susceptibility to mold and rot, and therefore required frequent rubbing and cleaning. To some extent it therefore was impractical, a proverbial labor of love. Dolphin molds were scarce; “the Mould, or Vat, was used to be lent from one Neighbour to another, throughout a Town,” incidentally making commercial production even unlikelier. (Ellis 98)

From the facts presented by Ellis, Deborah Valenze concludes that the practice of making Dolphin cheese “positively enhanced the co-operative spirit that existed within rural communities” and “served the multiple purpose of communicating neighbourly goodwill, female art, and material assistance at times of need.” (Past & Present 158)

This view of the rural past appears more than a little rose tinted and overblown, and maybe making Dolphin cheese was just a kind of generous fun; as Ellis intoned, an opportunity to gather and gossip, something like throwing a baby shower or dressing up to trick-or-treat for Unicef. An element of anachronism may have crept in as well, for it is difficult to picture an eighteenth century farmer, woman or man, with any concern about the transmission, let alone concept, of ‘female’ art.

Valenze’s analysis, however, does contain a certain truth. Eighteenth century accounts describe entire villages that shared the work of milking cows regardless of their ownership. In an era before industrialized agriculture, these people produced “their great cheeses,” meaning big ones, by organizing what is fair to describe as informal cooperatives. (Past & Present 158, 158n32) As Valenze observes, “[o]ne need not idealize the eighteenth-century farming community to find practices which, according to rational considerations, benefited the entire community rather than the individual dairy farmer. Here quality and commercial success were compatible with customary methods.” (Past & Present 158)

If Valenze may have a point about the relatively communal, even benign aspects of preindustrial rural life, she does take liberties. She offers no citation for her assertion that the production of Dolphin cheese was “a widely acclaimed custom” and Ellis, her only authority on the subject, makes no such claim. Valenze finds the placement of a dolphin on the cheese itself significant, as “symbolizing rescue from peril and resurrection from death.” (Past & Present 158) Ellis, however, adds that the dolphin was not the only image in the dairy; “some Dairy-maids have a Mould cut in the impression of a Plaice-fish on a Cheese, others in the figure of a Pompion.” (Ellis 98) It is unclear whether these molds also served to celebrate childbirth and assist the new mother, but if so it would be difficult to ascribe much mystical resonance to a big flounder or pumpkin.

None of this, of course, has gotten us any closer to eighteenth century Quebec. In the absence of any new revelation, the only conclusion has to be that the reference by Lafrance and Desloges to the importation of Dolphin cheese into eighteenth century Quebec is a mistake or canard.

Sources:

William Ellis, Agriculture improv’d: or, The practice of husbandry display’d (London 1745)

Robert Gibbs, Buckinghamshire: A History of Aylesbury with its borough and hundreds (Aylesbury, England 1885)

Marc Lafrance & Yvon Desloges, A Taste of History; The Origins of Quebec Cuisine (Quebec 1989)

Deborah Valenze, “The Art of Women and the Business of Men: Women’s Work and the Dairy Industry c. 1740-1840,” Past and Present No. 130 (February 1991) 142-69