An appreciation of Westerhall rum

The Editor usually is not enamored of white or light rums; instead of the intense tones of their darker cousins, light rums tend to exude a kind of sickly aura. Not Westerhall Plantation Rum. Our first sample of Westerhall appeared free of charge after a late dinner at the Star Top in Chicago.

The owners and their crew billed themselves as ‘alcoholists’ rather than alcoholics, a flimsy distinction. The liquid certainly did fuel the enterprise, and yet its off-center culinary style was none the worse for it. One of the owners apparently was, however, for sadly neither he nor the Star Top survives.

On the night of the Westerhall inaugural he had brought little cheese glasses to our table and filled them with the chilled rum before adding a grind of coarse black pepper to each drink. The shards floated to the base of each glass and the peppery rum became fiery ice. We still drink Westerhall that way when we can find it; nothing feels better after rich and feastly food.

We have not been able to find either the distiller’s Westerhall Vintage, a darker rum, or its ‘Superb Light,’ also, perversely, a darker product than the flagship ‘Plantation’ brand.

The rum, from Grenada, is produced in two steps. Westerhall distills a ‘flavour foundation’ from the juice of crushed pure cane in small copper kettles before adding a rum that is gold from aging in oak. It is not a single batch product: According to the company, “[l]ike cognac makers, we vary the proportion of our ingredients to achieve a certain flavour standard with every batch.”

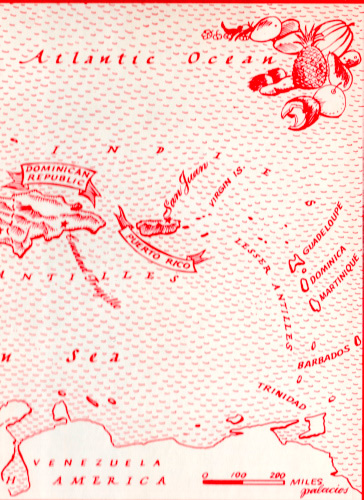

For our money, Westerhall defeats all the newly fashionable rhum agricoles from the French Caribbean, including Ten Cane (which, however, is not bad for light rum). It is cheaper too, usually running to under $25 for a standard 750 ml bottle.

The distillery itself has a colorful history. The Westerhall Estate was named early in the eighteenth century by Sir William John Stone, after his ancestral holdings in Dumfrieshire in the Scottish Borders. The estate originally produced bananas, cocoa, coconuts and limes in addition to cane, and distilled rum from the start. Cane mills, steam engines, iron water wheels and boilers imported from Glasgow still exist onsite. Despite this pedigree, however, Westerhall began bottling its rum only in 1974. Before then, all of its production shipped in bulk or cask.

Back in Chicago, the Star Top took its name from the shape of the burners on its commercial stoves. They were a wild and clever bunch. We miss them.