Arawak, African & English settlers on Barbados: The origins of Bajan food.

1. ‘Little England.’

Barbados, unlike just about every other island in the Caribbean, belonged to only one empire during its centuries of European and African habitation. It was the second Caribbean island occupied by the English after St. Kitts (technically St. Christopher, since defrocked) and in turn became a base for colonizing other territories. As the best historian of the English in the Caribbean explains, this process of settlement makes a “fascinating, sometimes incredible” story tinged with “a sad and somber side.” ( No Peace 4) Carl Bridenbaugh is disciplined and humane enough to recognize both the genius of the English who succeeded in the islands, a somberly small proportion of the settlers, and to decry the misery they inflicted on their slaves from Africa and indentured servants from the British Isles.

Queen’s flag, Barbados

Thus for example the great planter Richard Drax (incidentally someone who had an abiding interest in husbandry and food) “exhibited nearly every quality of the English country gentleman of the seventeenth century, the pioneer, and the founder of an empire: high intelligence, ambition, initiative, driving energy, courage, persuasiveness, and leadership.” ( No Peace 137) He also owned some 200 slaves in 1654, and probably had accepted the contracts of indentured servants ‘barbadosed,’ or shanghaied from the British Isles against their will before then. (Dunn 69)

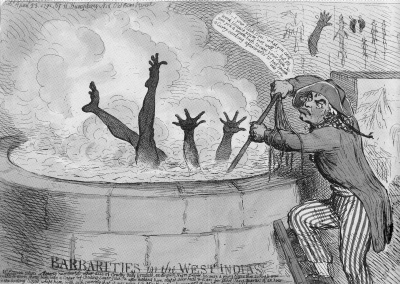

As Richard Dunn explains, Drax and other slaveholders “came from a society with no slaves but plenty of servants, domestic drudges, and farm laborers who spent their lives toiling for their betters in exchange for minimum requirements of food, clothing and shelter.” (Dunn 73) The step from that hierarchical society in seventeenth century England to the slave economies of the Caribbean was not steep. “The rape’s progress was fatally easy: from exploiting the English laboring poor to abusing colonial bondservants to ensnaring kidnaps and convicts to enslaving black Africans.” (Dunn 73) In such an atmosphere the acquisition of slaves was, in Winthrop Jordan’s words, an “unthinking decision,” as demonstrated by the dearth of apologia for the practice in any surviving records.

Drax

Barbados initially was named “Little England,” and Bajans consistently delighted in the nickname at least as recently as 1973--over a decade after independence. (Trollope 205; No Peace 101; Tree 1) In 1996, Jinx and Jefferson Morgan still could comment that “[t]here are those who say that Barbados is more English than England.” (Morgans 244)

None of the island histories discuss the origin of ‘Bajan’ (native whites, who are Bajan like everyone else, also are called ‘Bims’ and the island itself ‘Bimshire’) but the term apparently is a mere contraction of ‘Barbadian,’ an awkward mouthful shortened first to ‘Badian,’ then all the way to the ‘j.’

2. Spicing up Barbados.

It should not surprise us, therefore, that British foodways form the foundation of an island cuisine leavened with the influences of its climate and peoples. “The result,” in the judgment of Jessica B. Harris, “is a style of cooking that mixes the heartiness of British fare with the spiciness of things African, one that combines the bounty of local fruits and vegetables with the wealth of local waters.” ( Juice 31) While this description reflects the worn misperception that traditional British food lacks punch, the African influence on Barbadian food is indeed palpable. Harris should, however, also have included another early culture of Barbados, for although the Arawak people of the island have disappeared, their influence on its food endures. (Sworder iii; Wolfe 36-45) Chinese, Indians and Madeirans, who reached the island as indentured servants following the abolition of slavery in 1838, would later add to the culinary mix, if in lesser proportion than on other Caribbean islands. ( TLS )

When the first English settlers arrived on Barbados with their slaves and a company of Arawaks in 1627, the island was uninhabited, and may have been uninhabited for centuries. The Arawaks had petitioned the English to join them “ as free people ” (emphasis in 17 th century original) and the English obliged in exchange for the agreement of the Arawaks to teach them how to cultivate seeds and cuttings of foodstuffs native to the region but alien to Europe. The Arawaks upheld their part of the deal and the English enslaved them. “Few more outrageous displays of man’s ingratitude to man are recorded in the sad annals of English colonization.” ( No Peace 30)

It was a good thing that the settlers arrived with their seeds and cuttings because, even though they found dense jungle literally “to the water’s edge,” Barbados “was destitute of all food-bearing plants.” ( No Peace 42, 44; Town 9, 10) From the outset the settlers were successful in cultivating bananas, cassava, corn, lemons, limes, melons, oranges, pineapples, plantains, pulses, sweet potatoes and yams on patches of hastily cleared land. They also brought fowls and “soon the 170 or more white, red and black inhabitants were producing food enough to sustain themselves.” ( No Peace 44; Town 11)

A century earlier the Portuguese, who probably named Barbados after a strange indigenous tree, the bearded fig “whose branches throw out strange antennae that ultimately root in the earth,” (Town 10-11) had left a couple of pigs on the island. Unmolested by natural predators, the pigs had proliferated and grown to enormous size; some of those encountered by the English weighed 400 pounds: They slaughtered the pigs with indiscriminate abandon. ( No Peace 44-45)

A pig in paradise

This was a brief brush with paradise, for few of the settlers had had the means to eat much meat in England, but by gorging themselves on pork and wasting much more of it they promptly rendered the feral swine extinct. “Thus did Englishmen, with brutal thoroughness, make their first assault on the ecology of the Caribbean islands.” ( No Peace 45)

3. The pull of tradition.

The colonists also had tried unsuccessfully to grow wheat and other foodstuffs, illustrating the grip that traditional foodways held on them. As Bridenbaugh explains:

“One obvious trait perceivable in all colonists is that no matter how advanced or unorthodox in opinion or customs they may be, when it comes to diet they want food such as they had in their childhood. Even the most radical or obstreperous men yearn for pie like mother used to make. In food and drink they invariably turn out to be conservative; no human characteristic is more ingrained, and one must take cognizance of this fact in trying to understand the settlers’ intransigence in adapting themselves to conditions in their island homes.” ( No Peace 43-44)

But adapt they did, at least for a time, and the early Bajans were such successful farmers of cassava and other “unfamiliar grains” that by 1634 a Father Andrew White wrote that Barbados was “the granarie of all the Charybbies.” ( No Peace 44) Taught by the Arawaks to leach the poisonous moisture from cassava, settlers combined it with corn to make bread and other baked and griddled goods. ( No Peace 47-20)

4. Adaptation and integration.

During the initial years of settlement Barbadians added bonavist, a variant of kidney bean, along with cabbage, figs, guava, pawpaws and of course capiscum both hot and mild. By 1631 they were raising chickens, cows, ducks, peacocks, domestic pigs, pigeons and turkeys, a bird originally native to the Americas but first brought to the islands via England in the seventeenth century. ( No Peace 46)

The monotonous subsistence diet shared by all islanders regardless of social station during the earliest years does not much interest us, but distinctive dishes soon emerged. Amerindian influence contributed to Bajan specialties that include cassava pone (essentially a pancake and mentioned in print at least as early as 1657), coucou, jug jug, mock apple sauce and pepperpot. (Sworder iii)

The most enduring Amerindian legacy, however, is barbecue, a word and technique derived from the Arawak barbacoa . The barbacoa itself was “a grating of thin green sticks upon which meat was grilled above an open fire…. The Indians sliced their meat into thin strips, laid it upon the barbacoa and cooked it slowly, exposing it to the smoke of the fire below, which was constantly enhanced with the fat of the animal.” (Wolfe 39) Smoking the meat cured it and imparted the precise flavor we associate with all manner of slow cooked barbecue today.

Barbados, however, was not culinarily isolated after the earliest years. “Trade with North America, Europe and Africa brought a variety of foodstuffs which made living easier for the inhabitants. Probably the most important being salted fish which, to this day, remains a favourite on the Island [sic]…. ” (Sworder iii) In fact saltfish, called “poor John” ( No Peace 48) by seventeenth century settlers, usually cod but sometimes mackerel, was the most significant food import. In contrast to wet preserved stores like cured meat, saltfish was cheap, and would become not only a staple fed to slaves (Town 26-27), but also the foundation of various foods eaten by the entire population.

This was a place both tolerant and horrifying. Henry Whistler wrote in 1655 that Barbadians “have that liberty of conscience which we so long in England have fought for, but they do abuse it.” (Breen 153) Dutch, French, Irish, Scottish and even Portuguese Jews at the Indian Bridge inhabited the island in the early decades of settlement, and Barbados was “the first successful English colony in America to develop a society based on the large-scale employment of African slaves.” (Breen 153) Black and white men, for the island was overwhelmingly male in its first decades, died in droves from pathogens native to the Caribbean and transplanted from Africa with the slaves.

Most of the Irish were indentured servants despised by their masters more than the enslaved Africans, who were regarded as more valuable and therefore were better treated. Barbadian planters considered Irish immigrants “worthless” and passed a law, honored in the breach, barring them from the island in 1644. There were a lot of them in the seventeenth century Caribbean, over half of all white settlers, “who, incidentally, bequeathed a pronounced brogue [if no culinary influence] to English-speaking West Indians.” ( TLS )

Slaves ate variants of African dishes; “pounded poached corn” or more usually millet (‘sansam’), saltfish boiled with chilies and thickened with cassava or other flours (‘acra’), addictive calalu, a crab and okra stew made with pork fat and coconut. (Town 26)

5. What, no flying fish?

Fresh fish was another matter. Fried flying fish in particular is a Bajan specialty today, but such was not the case in the seventeenth century. It found its way to the streets of the port, called The Indian Bridge (now Bridgetown, the capital), but not to what quickly became the center of island life, the great plantations.

“Although the waters around Barbados teemed with many varieties of edible fish, it is astonishing to learn that they were seldom used for plantation food.” Why not? Is the absence of fish evidence of Englishmen unwilling to adapt, or of an oversight? The question has vexed historians, but not the perspicacious Bridenbaugh. It is hot in Barbados, so “fish spoiled within six hours of being caught and fishermen hastened to sell them to the taverns in the Indian Bridge rather than risk peddling them to the plantations that still could not be reached by path or road.” ( No Peace 48) It was the only town to develop anywhere in the Caribbean during the seventeenth century and for decades stood as the only safe harbor in the English islands. Elsewhere ships anchored offshore and took their chances.( No Peace 108)

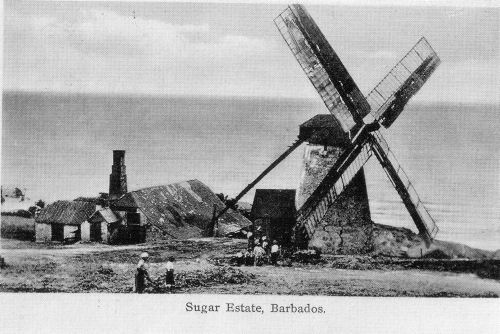

6. Sugar and spice…

If The Indian Bridge set Barbados apart, its plantations quickly dominated the rest of the landscape. Within several decades the island was deforested in favor of their crops, with profound effect upon its ecology: “Nearly all of the plants of Barbados today… are introduced species; virtually none of the original vegetation survives.” ( No Peace 271-72)

The growth of the colony was rapid, and Barbados had reached “about the same population size as Massachusetts or Virginia by 1640.” (Dunn 55) The sugar planters “were the wealthiest men in English America in 1680 and by the end of the century Barbados had become “the richest and most populous of the English colonies” (Dunn 26, 85) Its land was so fertile and its planters so enterprising that a visitor had written in 1676 that “there is not a foot of land in Barbados that is not employed even to the seaside.” In 1681, Sir Richard Dutton was astounded to find that “as for the Countrey, it is one great City adorned with gardens.” ( No Peace 293n3)

This clearance of the entire island had the unintended consequence, salutary for the planters and unsalubrious for their slaves, of denying fugitives any place to hack maroon settlements out of the wild. As Austin Clarke explains in Bajan dialect,

“Most o’ the other islands have hinterlands and jungles and bush. And in these islands they used to have a lot o’ slave rebellions. Barbadians didn’t have tummuch o’ these uprisings because we didn’t--and don’t--have hinterlands…. So, as Barbadians, we’re always a lil embarrassed through lack o’ forests and jungles and rebellions. Other Wessindians, like the Jamaicans and Guyanese, does sneer at we and say, ‘All-you don’t have no hinterlands. All-you don’t have no history. No slave revolts. What the arse-all you have?’” ( Pig Tails 174)

The answer, of course, was sugar. Cane would envelop the landscape during the eighteenth century, and it would make Barbados, or rather its planter elite, rich. It also would displace other crops, including foodstuffs, so that by the eighteenth century Barbadian grandees planted little food by volume other than sweet potatoes and yams (for their slaves) and so required imports from the British Isles and North America to feed them. (Dunn 67)

Trollope would report in 1860 that “every inch” of Bimshire was under cultivation with cane. (Trollope 193) The planters constituted “a tiny ruling oligarchy” that “ordered all human affairs in its own interest. They held that what was good for them was good for the colony…. These planters formed the only nearly complete social group in the Lesser Antilles.” ( No Peace 129)

In common with other Caribbean cuisines, sugar finds its way into a substantial number of savory dishes in Barbados. Contrary to received wisdom, however, cane did not crowd out all other crops from the outset of colonization. No society in the Caribbean had created a monoculture by the end of the seventeenth century, although the “Barbadians still produced more sugar in 1690 than the planters of any other Caribbean island.” ( No Peace 295, 346) They also cultivated significant yields of annatto, cotton, ginger, indigo and tobacco.

7… and everything nice.

Ginger, which for good reason features even in early recipes, brought substantial profits to Barbados. From 1681 through 1683, for example, Barbados and the Leewards exported “a remarkable total of 1,250,640 pounds of raw and preserved ginger.” ( No Peace 284) Similarly, during two months in 1690, Bridgetown (as it already had become) merchants shipped nearly 60,000 pounds of cotton to other colonies and over 60,000 pounds of it to England. ( No Peace 283)

The diet of white Barbadians had become “slight” by the 1640s; starvation was a real threat avoided only by outmigration. Servants, for example, subsisted on “peas, potatoes and roots” because a burgeoning white population outgrew the local produce and all those pigs had gone the way the carrier pigeon would go. In 1647, however, culinary conditions changed following the arrival of a remarkable visitor. “Richard Ligon was exceptional in his interest in diets, good eating, and wide knowledge of how to cook and prepare foods.” ( No Peace 47) He was, according to Bridenbaugh, “[ u ] n gastronome veritable (and a very early one) and dietician combined” who “taught the richest planters and merchants the pleasure of appetizing and well-prepared food” including “Fricases,” “Quelquechoses” and “Excellent Stews.” ( No Peace 49, 138)

Ligon did not confine his attentions to the tables of the wealthy: He not only improved the fare of inns at The Indian Bridge but also persuaded planters to supplement the rations of their indentured servants and slaves with fresh meat and salt fish. He took a close interest in the improvement of husbandry. Ligon learned from an old Arawak woman how to process cassava flour for mixing with corn to bake bread and pone, and even “acceptable cassava pie crusts.” ( No Peace 47, 47n20, 49; Dunn 273)

“Of his many contributions to the bettering of West Indian life, Ligon’s almost single-handed accomplishment in aiding both the whites and blacks to adjust their tastes to new world foods was the greatest and most lasting, and what he imparted to the Barbadians was quickly picked up by the planters of the other islands.” ( No Peace 49-50) Among these foods were bonavist and sweet potatoes; by the time Ligon left Barbados in 1650 the importation of both salt fish and “powder’d Beef” had increased substantially.

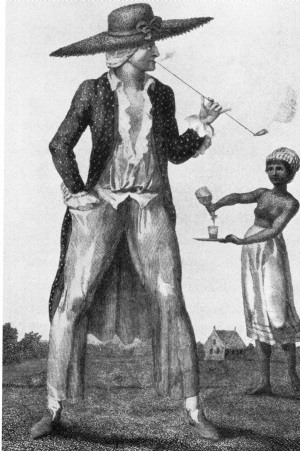

By the 1640s the confident planters’ elite had evolved a lavish reciprocal hospitality that endured into the nineteenth century, when Trollope marveled that “one meets with unbounded hospitality” throughout an island where “[n]o people ever praised themselves so constantly….” (Trollope 198, 205)

Planters kicking back.

8. The culinary court in the (tropical) country.

The amount and variety of food served at one banquet held in 1650 by Drax, “The First Gentleman of Barbados,” would be astonishing in any place at any time, and seems nearly unimaginable on a remote island outpost during the seventeenth century, a setting in which the expense of these banquets must have been colossal. Barbados and the rest of the English Caribbean, however, was an eccentric place. According to Dunn, Whistler found everything in the “fast-living, fast-dying” colony “lurid and bizarre.” (Dunn 77) “For the English and peoples of continental Europe, the seventeenth century was not fundamentally a materialist age; for the inhabitants of England’s Caribbean colonies, it was little else.” ( No Peace 35)

These were people looking for the main chance, people willing to gamble and willing to act with ruthless abandon. The society they created with their instant wealth was ostentatious, “boisterous and volatile.” (Dunn 79) “As Abbe Biet said bluntly of the ruling clique in Barbados, ‘They all came here in order to become rich.’” ( No Peace 35) When money is the sole means of keeping score, display, in matters culinary and otherwise, acquires a salient position in defining the social order.

Dunn has noted that the preferred English “diet of bread, beer and beef was not easily transplanted to the Caribbean,” (Dunn 273) but it would seem that at least some of the English some of the time managed to accomplish the feat. The dinner at the Drax plantation began with fourteen different dishes of beef, variously baked, boiled and roast; tongue and tripe pies seasoned with currants, herbs, suet and spice; an olio; a pork fricassee and collops; turkey, rabbits, ducks, doves, capon and boiled chickens; a potato pudding; suckling pig with a brain sauce found in English cookbooks from the seventeenth until early twentieth centuries; “a Kid with a pudding in his belly;” bacon; and tongues.

Preserved foods brought to the island included anchovies (always an English favorite), bottarga, caviar, olives and pickled oysters. The plantation itself made preserves including banana, guava and plantain. There were fraizes and tansies and more, and ten different tropical fruits to eat with custards and creams. There was everything alcoholic imaginable, from island drinks called beveridge made with sugar and orange, and mobbie made with fermented sweet potatoes that matured literally overnight and “tasted much like new Rhenish wine,” to “all spirits that come from England” along with wines from the Canaries, France, Germany, Madeira and Spain; and there was, of course, Kill-Devil (rum to twenty-first century drinkers) too. ( No Peace 50-51, 420-21)

This is a style of cooking that might have been called Tropical English: The prepared dishes reflect both the elegant ‘court’ and sturdy yeoman cookery of seventeenth century kitchens. Versions of the more elaborate preparations appear in Robert May’s Accomplish’d Cook of 1660: The Bims were up to date.

9. On to the future.

Nothing remains the same, and so Barbadian cuisine evolved to embrace such disparate influences as the poor and the chili. The national dish, a Saturday night standard like hot dogs and beans in New England, is pudding and souse. It incorporates ancient English technique and humble island ingredients. The pudding of yam or sweet potato is steamed; the souse is a brawn or headcheese of pork offcuts.

In Sky Juice and Flying Fish, Harris describes souse as “a spicy mixture of pig’s feet, snouts and tails (and more) served in a lime juice marinade along with green bell peppers, cucumber, onion slices, and fiery hot capiscum chillies [sic].” ( Sky Juice 31) She does not, however, provide a recipe, and there is little evidence of Barbados in this Caribbean cookbook: The few ‘Barbadian’ recipes are not at all unique to the island. Tomatoes ‘Atlantis,’ for example, are merely sliced, buttered and broiled; a clubland standard in London. Harris does provide a recipe for souse in Beyond Gumbo: Creole Fusion Food from the Atlantic Rim , but in her typically exasperating way does not include pig’s feet, snouts or tails in it.

10. Into the kitchen with Bajans.

No matter; other authors give us a good sense of the Bajan. Four in particular invite comment.

The first is not a cookbook at all, but rather a ‘culinary memoir’ from Austin Clarke, the exuberant Bajan scholar and novelist. His introduction provides a vivid description of Barbadian foodways during the 1930s and forties that descend unmistakably from seventeenth century sources.

The interwar landscape of Barbados looked much like it did to Richard Ligon and Anthony Trollope in earlier centuries. Where Clarke grew up outside of Bridgetown, most of the people were “[p]oor as a bird’s arse” and labored as field hands on the Wildey Plantation. “It was pretty as a postcard, with fields o’ sugar cane stretching to the horizon and beyond…. The Plantation was a pristine panorama of English pastoral beauty” where fig, plantain and banana trees grew amidst fields of sweet potatoes and tomatoes. ( Pig Tails 69) Wildey was a relatively humane employer by contemporary standards who nonetheless worked its laborers nearly to death. They, naturally, considered the plantation their enemy and stole what foods they could. ( Pig Tails 69-70) It was a specter from “an age of elegance, colonialism and oppression.” ( Pig Tails 185)

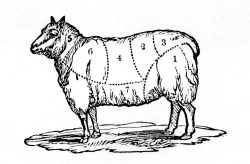

Like their ancestors and the planters who oppressed them, the Clarkes “kept ducks, along with fowls, sheep, a goat and pigs. And we kept turkeys.” ( Pig Tails 29) His mother “always made baked pork” in the English style, “with the skin done in a rich, golden crispy crackling, and she served it with peas and rice, sweet potato, cucumber ‘prickle….’” ( Pig Tails 30) Her fresh fish, purchased from hawkers in Bridgetown as it was in 1650, was “seasoned deeply with thyme, black pepper fresh from the tree, ginger and eschalots” for frying; salt cod became a “friggazee” that would be recognizable to Hannah Glasse or Eliza Acton. She made blood pudding too, and Bajan souse, with feet, ears and snouts. ( Pig Tails 8)

Clarke’s mother always made mutton soup on Wednesday. Hers was a hybrid of Scottish and Bajan ingredients; the lamb of course and a sheep’s head for texture and flavor, barley and dumplings; but also eddoes and salt pigtail and, “if it was the season for reaping corn,” yellow meal would supplement white flour to give those dumplings “a tantalizing heaviness.” ( Pig Tails 35-36) She cooked cassava pone and shopped for pickled fish: Salt beef flavored her vegetable stews and hearty soups.

Clarke himself is an enthusiastic and authentic Bajan cook who, in time honored vernacular style, disdains measurements and precise instructions. Like his mother, he takes some classic British dishes and alters them to reflect the Bajan taste for salt, spice and sugar.

His pea soup, for example, starts out as recognizably English but adds beef braised with lemon, the salt pigtails ubiquitous to Barbados, both sweet and “English” potatoes, and a jolt of grapefruit juice. The finish of cream and Sherry may be another English touch, but the dumplings that Clarke always simmers in the soup are seasoned with nutmeg and vanilla, and could include cassava flour. ( Pig Tails 164-72) The addition of meat and the potatoes is characteristically Barbadian; LaurelAnn Morley, a chef on the island, does the same thing but uses chicken instead of beef. (“ Old & New” 29)

This food is rich, even heavy for a hot climate, but nonetheless appealing and does confer a certain benefit; it is, as Clarke notes,

“the kind o’ food fit for a working man. For a lighterman. A man who does pull oars in a barge…. And more than that. It does make you perform good good in bed.” ( Pig Tails 164, 165)

Clarke cooks souse, a pepperpot with Amerindian origins and another recognizably Anglo-Bajan dish, oxtail with mushrooms and rice. He also is privileged to eat Privilege with the president of Barbados. Privilege is, unequivocally, “slave food,” that slaves and, later, ‘free’ plantation workers could “cut and contrive” from cheap imported foodstuffs along with the produce of their “two-by-two” garden plots. They grew chilies, garlic, okra, onions and thyme, and purchased rice, salt beef and… salt pigtails from “Away.” Much of their food came from abroad because even into the 1940s Barbadian planters cultivated sugar to the exclusion of little else. ( Pig Tails 60-65) These enumerated “ingreasements,” in Clarke’s Creole, combine to make Privilege. It is not unlike lobscouse with the addition of chili and rice. This and other ‘slave food’ became fashionable, but only in the 1960s, “when things got better, politically, financially and socially” in Barbados. Then, if “you was an artist or an intellectual, you would serve it to impress people that you remember your cultural roots.” ( Pig Tails 66)

The Barbados Cookbook is one of those spiral bound compilations beloved of Junior Leagues in the American south, and it is a good one, in this case published to benefit the Barbados Military Cemetery Association. Culinary historians consider these spiraled cookbooks reliable bellweathers of the food that people actually eat, especially if the book in question has been popular enough to sustain multiple editions, because cooks submit their families’ favorite recipes. By 1998 The Barbados Cookbook had entered its sixth printing, a more than respectable run for a volume sold only in as small a market as Barbados.

Although the book includes recipes found in any such volume of its time anywhere--moussaka, chicken piccata--they are a decided minority, and most of the preparations are remarkably consistent with Clarke’s narrative. Many dishes display both a pronounced British pedigree and the willingness to supplement original preparations with tropical spicing and ingredients. Peas soup appears here, in simpler mien than described by Clarke or Morley, but also fortified with something new, in this case pumpkin.

“Captain’s chicken” is a country captain, with raisins, along with “Southern Kedgeree;” both could have entered the island straight from the kitchens of the American south via the British Raj. An “Irish Special” is a simple variation on britishfoodinamerica’s beef Guinness. There are quintessentially British cheese straws, equally beloved at cocktail time throughout the wealthier precincts of the Caribbean, fish pie, potted meat, “Bimshire Bubble and Squeak” and brawn. Adaptation appears everywhere; “Sam’s Potted Chicken,” for example, grills instead of simmers the meat before mincing it to pot with flavorings of lemon juice, parsley and pepper instead of mace and cayenne: the bubble & squeak combines yam instead of potato with cabbage, a crop that has proliferated on Barbados since the English introduced it in the first third of the seventeenth century.

A third exemplar is from the set of TimeLife culinary essays accompanied by recipes covering the foods of the world back in the 1960s and seventies. Although a few factual errors creep into the text of The Cooking of the Caribbean Islands, the series in general displays a level of scholarship unequalled by Harris and most subsequent writers who have addressed Caribbean foodways. It also is a demonstration of how far the popular press has fallen in the intervening years.

The Cooking of the Caribbean Islands does not have much from Barbados, but what it has is good, including a suckling pig stuffed with olive and thyme rather than traditional sage and onion dressing; a “corn pone” that is not, but rather a cornmeal dessertcake made with cherries, raisins and vanilla; and a pepperpot attributed to Trinidad.

11. A singular chef: LaurelAnn Morley at The Cove.

The most comprehensive contemporary source of Barbadian preparations is Ms. Morley’s Caribbean Recipes “ Old & New .” It looks like a coffee table book with its full-page, full color food porn, rainbow page borders and lavish reproduction of original watercolors painted by her father. Do not be mistaken: This is a serious cookbook with interesting and accessible recipes, and does not even strive to promote her restaurant, The Cove on the eastern coast of the island.

Morley is no wordsmith, but the occasional awkward phrasing, sentence fragments and typographical errors only lend a certain charm to this obvious labor of love. It is something like a sunnier, decidedly less edgy but equally personal and authentic Caribbean version of Martin Picard’s acclaimed Album from Au Pied de Cochon in Montreal, his celebration of Quebeçois cuisine old and new.

The comparison is not as foolish as a superficial glance at the books might suggest. She is sunshine and wavy palms; he is bloody guts and rustic urban grit, but that would be beside the point. Both authors own working restaurants, and unlike celebrities elsewhere actually work there. They both self-published their manifestos, and that has freed them from conventional commercial constraint. Like “ Old & New ,” Pied de Cochon appears in large format to accommodate lots of photographs and artwork, and to give rein to its author’s whimsy. Some of Morley’s recipes include prefatory notes; others do not, and many of the watercolors have nothing to do with food. Morley strays off to other islands as she pleases betwixt her celebration of Bajan foodways, and we welcome the excursions. There is a heartfelt eulogy to her father and a ‘Pre-Chat’ on Caribbean foods, including a glossary incongruously illustrated with ‘Light Houses of Barbados.’ It coheres though, and as in Picard’s book, it all conveys a compelling sense of place. We want to visit The Cove, to chat with Ms. Morley and try her food.

Unlike Picard, whose technique can be complex and technical, Morley favors the vernacular; her recipes are succinct and simple. The Editor’s favorite part of Recipes “ Old & New ” are the chapters on one pot meals and “The Black ‘Buck’ Pots,” although she also returns repeatedly to the other sections of the book.

Buck pots are cast iron pans, pones and skillets as well as pots, and as beloved of Bajan cooks as their Yankee and Cajun counterparts. Like them, home cooks from Barbados will cook anything in cast iron to good effect. The favorite chapters include (of course) pudding and souse, pepperpot and suckling pig, but also roast beef with Yorkshire pudding, roast potatoes and pan gravy; a marinated Bajan variation on steak & kidney pie; chicken laced with Angostura, English herbs and Worcestershire; and a rabbit stew flavored with orange juice, zest and liqueur, Creole style.

A discernable cuisine emerges from these Barbadian books. They all include their own iterations of oxtail stew, pepperpot (originally Guyanese, as even the proud Clarke concedes, but enthusiastically adapted by him and other Bajans) and souse, all of them make extensive and imaginative use of salt cod, and they all cook with Sherry and rum. The food is hearty, just short of, and miles from, stodge. Like the food of Louisiana, this highly spiced Creole cuisine from a blistering climate is, oddly enough, suited to dark and wintry days too.

12. Island keepers of the flame.

The Barbadian books display something that bfia previously has noted in connection with foods like spiced beef; the widespread retention elsewhere of traditional recipes nearly lost to the British themselves. A noteworthy example from the Caribbean in general and Barbados in particular may be the proliferation of one pot dinners built around cowheel, a part of the steer anathema to mainstream America and unknown in Britain outside a few retrograde kitchens in the hardscrabble North.

Its unpopularity is understandable if misplaced: Cowheels are homely, even ugly ingredients. The otherwise broadminded Laura Mason provides a horror film description of them, “inelegant, long rags of pale creamy-white skin and gristle, usually with the bones showing.” (Mason & Brown 188)

There in the north of England cowheel lingered, particularly in Lancashire, into the late twentieth century. In 1954, Dorothy Hartley included recipes for a north country brawn and a stew; Mason and Brown explain that because of its ugliness, cow heel “was probably mostly left to the poor,” as it originally was in the Caribbean. (Hartley 80; Mason & Brown 189)

The Caribbean poor still relish it, as did the lesser sort of Victorian Londoner. In The Old Curiosity Shop, Dickens has an innkeeper describe a dish made with cowheel:

“‘It’s a stew of tripe,’ said the landlord, smacking his lips, ‘and cowheel,’ smacking them again, ‘and bacon,’ smacking them once more, ‘and steak,’ smacking them for a fourth time, ‘and peas, cawliflowers, new potatoes, and sparrow-grass, all working together in one delicious gravy.’”

Dickens was, despite his reputation as a reformer, no admirer of the workingman or his culture, so it is unclear whether or not his description of so proletarian a stew was intended to appall his middle class audience, but the description sounds enticing to the Editor--as it should to any tradition minded Bajan.

Cowheel appears in recipes up and down the Antilles for good reason. The connective tissue melts with long, slow cooking to give a viscous, almost silken and ungreasy texture to soups and stews. Cowheel features in a pepperpot from Harris; soup from Morley’s “ Old & New ;” cowfoot and beans in Jamaica (Benghiat 98-99); Clarke’s essays and elsewhere. It is a British classic alive (or rather, of course, dead) thanks to the robust folk memory of the Caribbean peoples.

Notes:

- According to Austin Clarke’s mother, a ‘vegetarian’ is anyone who cares (too) little about the quality of her or his food, whether or not the diner eats meat. “‘Someone who prefer bush and grass, as if they is sheep and cows, is somebody who don’t have enough food to put in his mouth.’” ( Pig’s Tails 68)

- The Editor is grateful to Damaal Hazelwood, scion of Barbados and New Jersey, for her copy of The Barbados Cookbook .

- Barbadians call tubers and root vegetables “ground provisions.”

- We think of pone as a griddle cake but in fact the term originally described the griddle itself.

- Like cooks from Haiti and Louisiana, Bajans keep on hand homemade mixtures of seasonings for spiking soup, stews and even roasted meat. Suggestions appear in the practical along with other Bajan recipes.

Sources:

Anon., “The West Indies: The Lure of the Islands,” Times Literary Supplement no. 1584 (29 December 1972)

Norma Benghiat, Traditional Jamaican Cookery (Hammondsworth, Middlesex 1985)

T. H. Breen & Timothy Hall, Colonial America in an Atlantic World (New York 2004)

Carl & Roberta Bridenbaugh, No Peace Beyond the Line: The English in the Caribbean 1624-1690 (New York 1972)

Austin Clarke, Pig Tails ‘n Breadfruit: A Culinary Memoir (New York 1999)

Richard Dunn, Sugar and Slaves: The Rise of the Planter Class in the English West Indies, 1624-1713 (New York 1972)

Jessica B. Harris, Beyond Gumbo: Creole Fusion Food from the Atlantic Rim (New York 2003)

Sky Juice and Flying Fish: Traditional Caribbean Cooking (New York 1991)

Dorothy Hartley, Food in England (London 1954)

Laura Mason & Catherine Brown, Traditional Foods of Britain (Totnes, Devon 1999)

Robert May, the Accomplish’t Cook (London 1660; Prospect Books facsimile 1990)

Jinx & Jefferson Morgan, The Sugar Mill Caribbean Cookbook (Boston 1996)

LaurelAnn Morley, Caribbean Recipes “Old & New ” (Bridgetown, Barbados 2006)

Peggy Sworder & Jill Hamilton, The Barbados Cookbook (Bridgetown, Barbados 1998)

Anthony Trollope, The West Indies and the Spanish Main (London 1860)

Linda Wolfe, The Cooking of the Caribbean Islands (New York 1970)

Bajan seasoning Beyond Gumbo 132; other ref.s; ck