Rumbullion & killdevil, or: Rum, the spirit of the Indies.

1. Spiritual origins.

It is unclear when the various alcohol distillates made their individual debuts; brandy probably first, in England, France or Italy; vodka and whisky later, in the Slavic and Celtic realms, but dates unknown. Some commentators (it would be unfair to scholars to identify them as such) hazily trace ‘evidence’ of alcohol distillation to the twelfth century and one writer states unequivocally, if without citation, that it “was invented in England in the 13th century.” (Hirst) That does not mean, however, that distilled alcohol was much in evidence until much later. The same writer who traces distillation as a technique to the thirteenth century contends that “early in the 16th century, distilled spirits were not widely available anywhere.” (Hirst)

No lesser light than Ferdinand Braudel takes a more cautious approach. He states that alcohol per se “was possibly discovered in about 1100, in southern Italy” and adds that the first distillation, probably of wine to make brandy or aqua vitae, “had been attributed (probably wrongly) to Raymond Lull who died in 1315, or to a curious itinerant doctor, Arnaud de Villenueve,” who died in 1313. (Braudel 241)

Whenever it first appeared, however, brandy “only broke away from doctors and apothecaries very slowly.” (Braudel 243) Customs records identify brandy merchants at Colmar in 1506, but not in Venice until 1596; its appearance in other sixteenth century locations remains conjectural, and after sifting the evidence Braudel admits “that we are still no nearer to the answer to the problem: when did distilling begin?” (Braudel 243, 248) In any event he considers distilled alcohol a “great innovation” and in his judgment “[t]he sixteenth century created it; the seventeenth century consolidated it; the eighteenth century popularized it.” (Braudel 241)

2. Rum begins on Barbados.

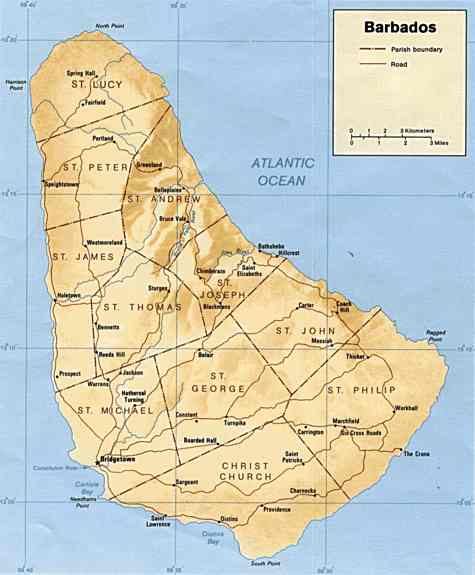

A little less mystery surrounds the genesis if not the name of the great spirit of the Caribees, and historically of New England and beyond. Rum began, on Barbados, sometime after 1640 and before 1647. Historically, distillates based on cane have started out as a byproduct of the sugar industry and that was true on seventeenth century Barbados. The cane was crushed to extract its juices, boiled to produce crystals and then ‘cured,’ or dried and drained of molasses. Sugar planters could sell the molasses, but it was bulky to transport and fetched a lower price, much lower, than the white sugar that Europe and New England craved.

Barbadian planters, however, found that “skimmings,” another byproduct of the refining process, quickly “soured,” or began to ferment. The addition of molasses to these fermented skimmings became the first step in converting byproducts of marginal utility to a powerful and profitable alcohol distillate that Barbados quickly began to export. (Ligon 92-93)

The Portuguese had produced sugar in Brazil for over a century before the English settled Barbados in 1627. Those planters in Brazil also produced a distilled drink from cane, agua ardente, but it probably was something closer to cachaca or vodka than to rum, and in particular the amber and darker rums produced by the English in the Caribbean. As Richard Dunn notes, they “were apparently the first sugar makers to discover how to distill molasses and other sugar by-products into a potent alcoholic drink with a sweetly burnished taste.” (Dunn 196)

“There are a number of small mysteries about the introduction of sugar culture to Barbados, but the main outline of the story is clear enough.” Arawaks who accompanied the English had planted cane on the island during the first year of settlement, but neither they nor the English knew how to make sugar and in any event the plants failed to flourish. (Dunn 61) Early cultivation of tobacco and cotton on Barbados produced indifferent results: By 1640 its enterprising and ambitious inhabitants had determined that the island needed a new crop. (Dunn 61; No Peace)

Tobacco didn’t work.

They settled on sugar, and at some point or points during 1640 and 1641 several of them made the journey to Pernambuco in Brazil to learn from the Portuguese how to make it. They were fast studies. By 1643 Thomas Robinson could write that Bardados “is growne the most flourishing Island in all those American parts, and I verily believe in all the world for the producing of sugar…. ” (Dunn 61, 61n37)

3. Rum gains a name for itself.

Rum followed sugar no later than 1647, if not at first by that name. As late as 1657 it was known as kill-devill, either or both because “a man who imbibed it promptly became boisterous, reckless and daring” or, as the polymath Richard Ligon believed in 1647, it had “the vertue to cure” slaves of illness contracted due to exposure during cold nights; “it drove the devil out of them.” (No Peace 91, 91n33)

“Somehow, somewhere, for its origin is obscure, kill-devil acquired a new name.” (No Peace 92) In 1650 an unknown Barbadian despaired that “[t]he chief fudling they make in this Iland is Rumbullion, alias Kill Divill, and this is made of Suggar cones distilled; a hot hellish and terrible liquor.” (No Peace 92) The derivation of rumbullion, shortened in a few years to rum, is conjectural and has been ascribed to various sources. The likeliest is ‘rumbustion,’ in seventeenth century usage as rumpus or tumult, the state that drinkers of it quickly acquired, for this hot and hellish drink was strong indeed.

4. What it was.

In strength if not in flavor, seventeenth century rumbullion probably resembled the ‘overproofs’ of as much as seventy-five percent or more alcohol available today. A seventeenth century Barbadian statute “stipulated that any rum that would not take fire from a flame without being heated had to be thrown away or the maker would be fined L100,” a considerable sum. (No Peace 297)

Evidence from the reliable Ligon bears out the notion of extreme alcoholic strength. He reported that Barbadian rum was

“so strong a Spirit, as a candle being brought to a neer distance, to the bung of a Hogshead or Butt, where itt is kept, the Spirits will flie to it, and taking hold of it, bring the fire down to the vessel, and set all a fire, which immediately breakse the vessel, and becomes a flame, burning all about it that is combustible matter.” (Ligon 93)

In a much cited anecdote, Ligon went on to add that an unfortunate slave (“an excellent servant”) sent to fetch rum from the “Still-house” hogshead to “the Drink-room” burned to death when he held a candle too close to the open cask. (Ligon 93)

5. Where it went.

It took a few years for the English and New Englanders to acquire a taste for rum. Even in Barbados, ships laden entirely with brandy found a ready market as late as 1654 (No Peace 421n2), and that same year the mutiny of an English crew in the Caribbean was only just averted when their captain neglected to ship the brandy ration, “but seldom thereafter does one read about that liquor; all is about rum.” (No Peace 296) Although little rum had reached New England by 1650, the market quickly expanded and “demand was almost universal by 1670.” (No Peace 1670)

According to Eric Williams, Caribbean exports of rum to England alone increased from about 100,000 gallons in 1700 to 3,341,020 in the fateful year of 1776.(Williams 220) Some accounts reckon rum the single most valuable item produced in New England during at least a portion of the 1700s. By the end of the eighteenth century, hundreds of rum distilleries operated all around the Atlantic basin, from the South American mainland across the Caribbean up into the Canadian maritimes and across the sea to England and Scotland, which evolved its own style of rich rum. India produces rum, and Khukri, the aptly named Nepalese distillate, is superb value for money even if wasteful of booze miles in a warming age.

6. How it looked.

It was not just New England. By the eighteenth century, rum had climbed the pinnacle of economic significance: “Not until oil was any single commodity so important for world trade.” (Williams) This was not, however, the “bland, branded,” white rum made by Bacardi with cheap and subsidized high fructose corn syrup. (Williams) Instead, distillers throughout the western world produced hundreds of distinctive products. As early as 1687 rum was considered “a very noble, lofty, clean Brandy” and was rapidly supplanting other spirits in the English market. These spirits ranged in color from a pale amber (think Westerhall and the slightly darker Mount Gay) to mahogany (like Barbancourt) all the way to black (Coruba, Wood’s or Cruzan Blackstrap). These darker rums had, and have, complex and distinctive flavors that rival the best spirits made from grain or fruits.

To be fair (the Editor favors big dark rums) light rums can be good too. Despite the ascendancy of Bacardi, which given its corn adjunct may not really be rum at all, hundreds of beguiling variants light and dark emerge from these distilleries the world over. Sugar is a versatile basis for distillation, and rum styles run the course from the light, sprightly rhum agricoles (as distinct from industrielle) that the French Caribbean departments have developed to 16 year old Bristol Classic Rum made on Barbados in the single Rockley Still. Bristol Classic gets long aging in fino Sherry casks and could nearly pass for an eccentic Islay malt whisky while still remaining redolent of rum.

7. The return of rum to America.

By the end of the twentieth century, rum production had ceased not just in New England, but throughout the United States. That has changed. Distilleries operate once again in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, also in Louisiana, Tennessee and elsewhere. Newfoundland produces a good dark rum with a nuanced nose, Screech. The American results are mixed, but the rums from Celebration Distillation in New Orleans have a distinctive and the pleasing taste of bananas. Thomas Tew out of Newport, named for the City by the Sea’s own pirate, is pretty good too and keeps improving with each small batch. They all are welcome back, even the less successful versions, so long as they keep trying.

Why is the rum always gone? Oh.

8. Bad books on rum.

It is surprising how little has been written about rum, and depressing how bad much of it is. One popular book, Rum by Dave Broom, is particularly unreliable despite its confident tone. To address only two examples, Broom states that “[s]ugar production, and thereby distilling” in “[w]hat is now the U.S. Virgin Islands” (in fact he addresses only St. Croix), “was kicked off by the French in the early seventeenth century, but grew in importance--and volume--when British planters arrived…. ” (Broom 78)

Broom provides no authority for the assertion, however, and none is found in the work of Carl Bridenbaugh, Dunn or any other serious historian of the subject who has been discovered by the Editor. In fact, the mercantilist French crown prohibited the importation of colonial molasses or rum, and prohibited Caribbean planters from selling cane products in British North America, to protect the domestic brandy industry from competition. Vast stocks of molasses therefore were thrown away. (No Peace 297n50)

Broom also describes seventeenth century Barbados as “an almost mythical place, a fantastical, fertile island where fortunes could be made with virtually no effort. It soon became painfully fashionable.” (Broom 92) Visitors to Barbados did find the place ‘fantastical,’ but not in a way that Broom implies, and its was a fertile environment, particularly for the cultivation of cane, at least until the planters exhausted its soil. Otherwise his breezy contentions are wrong.

In 1655, a visitor described Barbados as “the Dunghill wharone England doth cast forth its rubidg: Rodgs. Hors and such like people, which are generally brought heare.” (Parker 48) Much of this rubbish disappeared quickly. The mortality rate in seventeenth and eighteenth century Barbados was terrifying, and death “arrived from every conceivable direction.” (Mitchell) Disease vied with famine, hurricanes, tidal waves, pirates, privateers, foreign raiders and the dislocation of war for the title of grimmest reaper.

All of the island settlements were precarious: “All of life, everywhere, depended on wooden hulls” for foodstuffs and staples, tools and trade. (No Peace 62) In the circumstances, survival let alone the acquisition of fortunes required prodigious effort leavened with luck. Most settlers failed and left Barbados.

For those left on the island, fortune meant sugar, and the product was a harsh mistress. Transplanting the sugar culture from Brazil to Barbados was “complicated and costly.” (No Peace 76) Once the industry did reach the island, its requirements in a preindustrial world were forbidding. “That the work of managing a sugar plantation demanded all of the time, intelligence, and energy of the owner must be immediately recognized.” (No Peace 92)

If some, a very few, Barbadian planters did become immensely rich overnight, the dawn was a long time coming. It took over two decades for the pioneer planters to gain prosperity, and as the value of their crops increased, so did the value of land on the island, making access to vaster and vaster sums of capital crucial to the profitable planting, tending, harvest, refining and distilling of the cane.

As to fashion, “[i]n the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, no one had a good word to say about the West Indies,” Barbados not excepted. It was not just the denizens of the Barbadian underclass that the English despised; the privileged classes envied and snubbed the sugar barons as parvenus, the kind of people who, to plagiarize Alan Clarke on Michael Heseltine, had to buy their own furniture.

It would be unfair to continue piling on, but worst of all Broom does not even include in his international directory of rums the Editor’s three favorites: Coruba, Pampero Anniversario and Westerhall.

Edward Hamilton’s Rums of the Eastern Caribbean is not much better than Broom’s Rum. It is an anecdotal ‘history’ and distillery guidebook with all the factual errors that the approach usually entails, and the editing is sloppy; Grenada, for example appears on page after page as ‘Grenda.’ Hamilton’s prose is clumsy but charming in its way and he avoids Broom’s grandiose glibness. There is, however, too much implausible speculation about the origin of the word ‘rum;’ if it comes from the suffix of Latin for cane, saccharum officinarum (“a clear link to the word derived from it,” Hamilton 7), then thousands of other things must also be called rum. It is simply an indication of the neuter gender.

Hamilton is good when he turns to the vulgate though, and it was fun to learn that vernacular terms for rhum include flibuste, guidive and tafia on the Francophone islands and for rum include babash, culture, forest preserve, hammond and hogo in the Anglophone territories. It may, however, have been as unnecessary to explain that rum produced locally sometimes is called “local rum” as it is to confide that bats in “the cool, moist darkness” of a warehouse “can be a little disturbing to unsuspecting tourists.” (Hamilton 7, 140)

There are instructions to make rum drinks and a few recipes that are either inadequately explained or painfully obvious.

Notes:

Notes:

- A thriving post-Annales school of historiography has developed. Practitioners like David Abulafia at Cambridge University emphasize the primacy of human will and structures both physical and political on historical phenomena. Human enterprise, whether the choice of crops to plant or goods to trade, is more important in this view than the natural world that Braudel considers paramount.

- Bridenbaugh dates the development of the sugar culture on Barbados, as well as the expansion of sugar trading, a little later than the sequence outlined by Dunn and adopted here. Both studies of the English in the Caribbean are superb, and without recourse to a raft of primary sources, our choice must be considered arbitrary.

Sources:

Fernand Braudel, The Structures of Everyday Life: Civilization & Capitalism, 15th-18th

Century, Volume I: The Limits of the Possible (New York 1981)

Carl and Roberta Bridenbaugh, No Peace Beyond the Line: The English in the Caribbean,

1624-1690 (New York 1972)

Dave Broom, Rum, (New York 2003)

Richard Dunn, Sugar & Slaves: The Rise of the Planter Class in the English West Indies,

1624-1713 (New York 1972)

Edward Hamilton, Rums of the Eastern Caribbean (Culebra, PR 1995)

K. Kris Hirst, “The History of Distilling,” http://archaeology.about.com/od/foodsoftheancientpast/fr/smith06.htm

Richard Ligon, A True & Exact History of the Iland of Barbados (London 1657;

Early English Books Online facsimile 2011)

Leslie Mitchell, “White Gold,” Literary Review (May 2011)

Matthew Parker, The Sugar Barons: Family, Corruption, Empire and War (London 2011)

Eric Williams, From Columbus to Castro: The History of the Caribbean, 1492-1969

(New York 1970)

Ian Williams, “The Secret History of Rum,” The Nation (5 December 2005)