The North remembers: Robert Owen Brown & the revival of Lancastrian cooking.

It is hard to believe for anyone who drank at the dump that it was during the 1980s, but Robert Owen Brown invaded the kitchen of the Mark Addy in Manchester during 2009 and converted the riverside public house to one of the best restaurants in Britain. It also is hard to believe that the Addy, or rather an Addy with Brown in its kitchen, is gone.

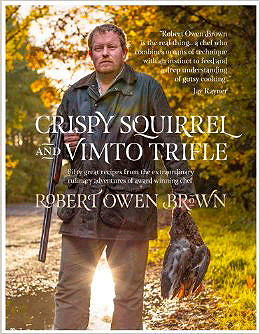

Hard to believe because based on his notices and the evidence of his book, Crispy Squirrel and Vimto Trifle , Owen Brown is a formidable cook, a cook courageous enough to embrace the idiom of the North, a region of England often despised by the sprawling and drawling cosmopolis to its south. Not so hard to believe, however, because Owen Brown never has lasted for long anywhere and says the place had become so decrepit that the cost of repair was prohibitive and the lease too high.

The space was anyway always problematic, something like a gaudy dance club superimposed without much conviction over a plasticized dive. Jay Rayner describes the Addy as

“a mixture of wonderful bare-brick arches, and 70s additions--smoked glass, modern window frames--which will be equally wonderful when someone gets round to destroying them. The current team cannot, by the terms of the lease, do anything about these interiors issues. But with Owen Butler in the kitchen, they have created the kind of gutsy gastro pub Manchester deserves.” (Rayner)

More properly, the Addy was and is in Salford, the town divided from Manchester by the River Irwell but otherwise in practical terms a precinct in Lancashire’s great city. Back in the era of restrictive licensing laws, Salford allowed public houses an hour more opening time than Manchester proper so the Addy, asquat beneath city streets on the quayside of the river, allowed a pint and dram of last resort. Otherwise it offered no particular attraction.

Then came Owen Brown. Although Rayner fails to note the fact, it is entirely appropriate that his review of the Addy appeared on St. George’s Day. Owen Brown cooks his own version of English food that is, Neil Sowerby claims, “rooted in the North West soil and its industrial heritage” and Owen Brown himself claims the great eighteenth century Mancunian Elizabeth Raffald as an abiding influence. (Brown 14, 15, 130)

It is hard to imagine how the ‘industrial heritage’ of the urban North can have influenced English foodways except in a bad way, and equally difficult to detect the invisible hand of Mrs. Raffald in the dishes described by Owen Brown.

He is nothing if not serious, but no mere antiquarian, and a stickler for detail notwithstanding the modest pedigree of many of the dishes he chooses. Here is what amounts to his own summary manifesto:

“Old-fashioned? No. Authentic? Yes. But not rigid. Some of my dishes are steeped in history and true to their roots. Some of my food has been kicked up the arse all the way into the 21st century.” (Owen Brown 11)

A sensible as well as bluff Northerner, Owen Brown fishes, forages and hunts too, and uses “rapeseed oil instead of olive oil because it is British and sustainable. It also is delicious and better to fry with.” Lard and suet for pastry of course; this after all is England. (Owen Brown 8)

Owen Brown and Fergus Henderson are friends: “The two,” again according to Rayner, “are famous for disappearing off to drink beer and oysters in the small hours.” They also share common interests in the renewal and reimagination of traditional English food. Conventional wisdom links their cooking styles but as with Mrs. Raffald it is hard to read Owen Brown’s recipes and infer any such influence other than an affinity for offal shared at this point by chefs, and some home cooks for that matter, all over Britain. And as Rayner has the insight to note, “St. John in London is a great restaurant, but it is also a self-conscious statement. It is dinner for the design crowd. At the Mark Addy it is,” or was at this remove, “just dinner.” (Rayner)

And what dinner it must have been. Owen Brown has the audacity to highlight not only characteristic northern items like black pudding, tripe and Vimto but also the plainest of workingclass preparations. A diner might begin with a terrine of black pudding and duck liver, move on to tripe--either pickled in the workingclass manner or made sticky with Madeira and of course onions, then end dinner with the Vimto trifle.

Vimto (shortened from the original ‘vim’ and ‘Tonic’) is, Owen Brown contends, “the iconic drink that was created in the North West and conquered the world,” but his claim is something like the New Yorkers’ view of the world according to Saul Steinberg. A proud northerner might hope Vimto has covered the earth but while it found footholds in the nations of the lost British Empire and latterly Europe it has not penetrated the western hemisphere except for British Guyana.

To the uninitiated Vimto is weird stuff, a syrup (or ‘cordial’) of blackcurrent, grape and raspberry juices flavored with small amounts of other fruit, some herbs and spice for dilution with water to drink hot (even weirder) or a sparkling version for service cold.

The origin, growth patterns and contemporary commemoration of Vimto are weird enough as well. John Noel Nichols from Manchester created it in 1908 “as a healthful ‘temperance’ drink.” The absence of alcohol explains its popularity in Muslim countries throughout the Middle East, but nothing explains the titanic and ridiculous ‘Monument to Vimto’ erected on the site of the original factory “representing the ingredients of the drink” in 1992. (Lloyd-Hughes 73)

Owen Brown combines hot Vimto “made as strong as you like” with blackberries , raspberries, the traditional ‘sponge’ or lady fingers and a rich custard that, he admits, is “a bit of a cheat.” It is all the better for that, an accessible formula simple enough for the most unaccomplished cook. The only problem with the recipe, for Americans anyway, is the scarcity of the Vimto. (Owen Brown 147)

Alternatively choose a program that entails chilled pea soup, sand dab with bacon and scallions, a serious contender for the holy trinity of culinary gods, followed by an Eccles cake with clotted cream.

Other dishes, like Owen Brown’s Lancashire omelet, his mother’s hotpot, faggots, a coddled egg with finnan haddie and the plain rag pudding, might not make it onto most restaurant menus but ought to be cooked with frequency at home. These things get their inspiration from the diet of workingclass northerners or, in the case of his “classic rag pudding,” emerge unalloyed from their kitchens.

They are cheap to make. Hot pot requires a humble lamb cut, from the neck, and some kidneys that cost nearly nothing; the egg uses but a scrap of fish; and the pudding may be assembled for a buck or quid or two.

If Heston Blumenthal has reinvented both court and gentry cookery from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries at Dinner, his London restaurant of stratospheric quality and cost, with a flamboyant imagination, Owen Brown has tweaked the food of eighteenth and nineteenth century tenant farmers and (some of the better-off ) urban workers hewing to their rural roots in a manner most respectful of tradition.

The rag pudding is a revelation. It is, as Owen Brown insists, “perhaps Oldham’s greatest contribution to cuisine, and while that bar is, we should admit, pretty low, the pudding’s flavor is profound. An apotheosis of simplicity, it wraps suet pastry around a filling only of ground beef, carrot, onion and stock for stewing in that rag.

Glyn Lloyd-Hughes concurs with Owen Brown on the Lancashire origin of rag pudding and notes that other varieties of minced meat, “often including offal,” also may be “folded into a very thin pastry, usually of rectangular form.” The rag pastry is by tradition considerably thinner than the dough used for other puddings so the Oldham invention is that anomaly among them, a light, almost even delicate dish. (Llloyd-Hughes 130)

Elemental in its intensity, the pudding is, as Owen Brown explains, “poor folk’s food with no herbs or spices--and it’s delicious.” Blumenthal is unlikely to take notice: “You can’t ‘deconstruct’ this kind of dish--or hotpot--they are perfect just as they are.” (Owen Brown 84) It is his loss.

Beyond the quality of its recipes, Crispy Squirrel is welcome because nearly nothing else covers the culinary traditions of the Manchester conurbation. When the hairy bikers embarked on their televised ‘food tour’ of Britain, for example, they cited only hotpot as a traditional Lancastrian dish.

Elsewhere in the North Northumberland and Yorkshire share a champion in the accomplished Peter Brears but Lancashire has languished undocumented. The justly celebrated Mrs. Raffald did live in Manchester and also Salford for a time, and The Experienced English Housekeeper was an eighteenth century bestseller surpassed only by Hannah Glasse. Like her Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy , however, Mrs. Raffald’s Housekeeper does not concentrate on the foodways of either Lancashire in particular or the North in general but rather covers the whole of England.

At the end of 2015, Meze Publishing issued The Manchester Cook Book , one of a series of promotional vehicles for restaurants, food shops and producers from various English regions including Cambridgeshire. It should be a welcome corrective to the neglect of Manchester, but like the other volumes in the series says comparatively little about the historical foodways of the city it covers.

Not that Manchester is a bad cookbook; it is not. There is nothing terribly Mancunian, however, about many of its dishes. While the book does include entries from as far afield as India and Italy, many of them are English. With a noteworthy exception, however, it is hard to claim anything for Manchester itself.

The Bury Black Pudding Company is perhaps the oldest and now the last producer of the blood sausage in Bury itself, the town north of Manchester associated most closely with the product. For their contribution to The Manchester Cook Book, the company commonsensically laces the classic Lancastrian hot pot with black pudding instead of the optional but ubiquitous kidney, and the variation is good. Other contributors might have consulted Owen Brown.

So if you would like to immerse yourself in the proud, proletarian, free-trading Dissenting tradition of Manchester through the expression of its foods, if only for a time, turn to Robert Owen Brown. He will not let you down.

Good recipes based on Crispy Squirrel and Vimto Trifle appear in the practical.

Sources:

Robert Owen Brown, Crispy Squirrel and Vimto Trifle (Manchester 2013)

Si King & Dave Myers, The Hairy Bikers’ Food Tour of Britain (London 2009)

Glyn Lloyd-Jones, The Foods of England (Adlington, Lancs. 2010)

Elizabeth Raffald, The Experienced English Housekeeper (Southover Press reprint, Lewes 1997; orig. publ. Manchester 1769)

Jay Rayner, “Restaurant review: The Mark Addy,” The Guardian (23 April 2011)

Anna Tebble, The Manchester Cook Book (Sheffield 2015)

www.vimto.co.uk (accessed 13 January 2016)