Found in California via Surrey, the American south & even New England, and a note on Row 34 in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

In 1958 Rupert Croft-Cooke wrote a memoir of his childhood in Surrey. One of the subjects he recounted in The Gardens of Camelot is the food his family cooked and ate between the wars. Like many Englishmen of his, or any, time, Croft-Cooke’s father, Hubert Cooke, was an avid gardener, or at least he avidly supervised his gardener. Their garden supplied the family with the bulk of its vegetables, always seasonal and always fresh.

Unlike most of his peers, Cooke himself purchased the fish and meat (Croft-Cooke does not remember much game) that his family ate instead of delegating the duty to servant or spouse. As Croft-Cooke recounts, his “father really cared and knew about food.” ( Gardens 87, 101)

The Cookes’ cook used these exemplary ingredients to create “almost nothing but traditional English dishes…. ” “What English cooking had,” as Croft-Cooke explains, “and where it survives still has--is daring. It dismisses complicated flavours and the use of too many ingredients and concentrates on the principal one.” ( Gardens 87, 95) Vegetables were simply prepared, carefully cooked (not cooked to muck) and flavored with nothing other than butter, salt and pepper.

In a similar vein, “the sternest simplicity was used… in the treatment of fish;” because the quality of the fish Cooke selected was so high the minimalist treatment “was effective.” Stern simplicity was not synonymous with simple-mindedness. An English standard like dressed crab was “mixed with a little vinegar, olive oil (so much for Elizabeth David’s claim that olive oil had been unknown to the English until the 1960s), salt and… cayenne pepper.” ( Gardens 95)

Mackerel was soused, the English seviche; whitebait got its moment in the deepfryer, scallops “were cooked in several ways, not because they needed variation, but because they were so delectable in each.” ( Gardens 96-97)

“Meat was treated with the same confidence” in the family kitchen. Cooke “bought only English or Scotch beef, and wanted it roast simply and in no way messed about.” ( Gardens 97)

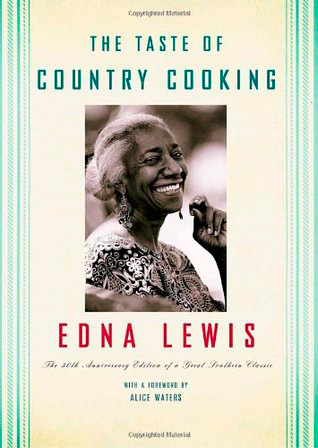

If this kind of English cooking sounds like it stole a long march on Alice Waters and the practitioners of ‘California cuisine,’ it did, whether they knew it or not. Waters herself nearly knows: She recently gave Edna Lewis credit for inspiring the movement. “I was such a Francophile, but when I discovered her cookbook, it felt like a terribly good friend…. I had never really considered Southern food before, but I learned from her that it’s completely connected to nature, totally in time and place.” (Lam 50-51)

Waters is referring to The Taste of Country Cooking , the wonderful book that the incomparable Lewis published in 1976. Her recipes and, perhaps even more indispensible, her vignettes of the African-American south, are all her own and anchored in the region, but their ethos, along with many other antecedents of its technique, is English. ( see, e.g., Perkins)

Country Cooking would have been welcome in an English kitchen. Take, for example, “an early summer dinner.” Its centerpiece of kidney cooked with bacon and wine steps lively from the English ranks and the Lewis family “always saved the suet from the kidney… for frying doughnuts and using in general.” (Lewis 66) Suet itself has been an English staple for centuries, while it remains unknown to the French (they have no word for it), but who in America turns to it today?

Summer scallions get a fast flash in butter, any English gardener might have pulled the simple Lewis salad of lettuce and beet greens, nothing more, from a Surrey garden, and her dessert of wild strawberries in cream is an epitome of English foodways. Even the spoonbread, while unmistakably original and southern, represents an adaptation of early English baking to the staples (notably corn and buttermilk) of the New World.

Elsewhere Lewis braises mutton in the English manner; forages for watercress, the most English of greens; cooks the fried oysters that abounded on the streets of eighteenth century London; and bakes bread pudding for service with custard, another quintessential English sweet. Kidney pie requires no elaboration, liver pudding looks a lot like haslet, and both fruitcake and mince pies were fixtures on the Christmas sideboard in the Lewis house. As a sort of charming footnote, she confides that her dandelion blossom wine was misnamed and might have been considered Scots: “We called it a wine but it was more like a liqueur and tasted a bit like clear Drambuie.” (Lewis 26)

Waters is not unacquainted with New England and might have found the same inspiration there. Over the years she has spent Thanksgiving at the house of friends in Watch Hill, Rhode Island, cooking the traditional dinner with some twists for a lucky crowd. She would bring with her a number of ingredients from Berkeley, but chose her wines from the selection at Dick’s in Westerly and bought oysters in New England. (Apple)

Huge “escapee” oysters in Watch Hill, RI (they still tasted great).

As in the majority of eighteenth century English cookbooks, American Cookery by Amelia Simmons makes lavish use of oysters. First published in Hartford during 1796, conventional wisdom considers it the first American cookbook, but whether the claim can withstand the rigorous scrutiny of Keith Stavely and Kathleen Fitzgerald remains unknown until their study of the slight forty-eight page volume appears. In the meantime it bears noting that except for a couple of strays like Indian pudding, the ‘receipts’ in American Cookery betray a suspiciously British cast.

In the manner that T. S. Eliot exerted influence on Shakespeare, Waters and Cooke would have influenced Simmons. Her vegetables are barely cooked and presented with utmost simplicity. It is necessary to “boil up” green beans “quick, they will be done soon and they will look of a better green than when growing in the garden.” (Simmons 100)

Asparagus becomes an intriguing dish in the hands of Simmons. To ensure uniform cooking, she separates head and shaft, scraping the tough skin of the shaft down to the tender white flesh, then “tie[s] them up in small even bundles.” Like those beans, the bifurcated spears require careful treatment; “boil them up quick; but by over boiling they,” like the Bourbons, “will lose their heads.” The ‘modernity’ of the recipe appears astonishing:

“[C]ut a slice of bread for toast, and toast it brown on both sides;… dip the toast in the asparagus water;… then lay the heads of the asparagus on it, with the white ends outwards; pour a little melted butter over the heads; cut an orange into small pieces, and stick them between for garnish.” (Simmons 101)

This is food fit for the most fastidious vegetarian or anyone else.

It is unclear, however, just what Simmons means by ‘melted butter,’ a historical term that has bedeviled contemporary writers and cooks. Simmons may have been advising her audience to melt some butter; she also may be calling for a lost sauce that would have been known to most if not all of her readers. Melted butter was a sauce familiar to the eighteenth century English in both North America and the British Isles.

According to the ebullient William Kitchener, whose Cook’s Oracle first appeared in 1817 and remained in print into the second half of the nineteenth century, “it must be always on the table. ” (Kitchener 13; emphasis in original) The sauce was indeed ubiquitous, prompting Voltaire’s famous if perhaps apocryphal quip that the English had but a single sauce. As early as his first edition of The Cook’s Oracle , however, Dr. Kitchener had noted a decline in the quality of melted butter; and as Sheila Hutchins wrote in 1967, “though excellent it is entirely forgotten.” (Hutchins 86) Seven years later, the great Jane Grigson predicted its return:

“I suspect that melted butter, or English butter sauce, is in for a come-back. With the popularity of the nouvelle cuisine , the light but rich texture of butter thickened sauces has become popular again.” (Grigson 352)

The prophecy went awry--a rare occasion where the judgment of Mrs. Grigson proved unsound--and melted butter remains in culinary remission.

The sauce itself is simple enough, an emulsion of butter, flour and just about any palatable liquid, and can be flavored in any number of ways. It was, Dr. Kitchener explains, “THE FOUNDATION OF ALMOST ALL OUR ENGLISH SAUCES; we have Melted Butter and Oysters, Parsley, Anchovies, Eggs, Shrimps, Lobster, Capers, &c. &c. &c.” (Kitchener 13; emphasis in original)

Whether or not melted butter may be taken at face value in American Cookery , its handling of meat presages twenty-first century doctrine. Beef must be roast over a “brisk hot fire” and should not be overcooked; “rare done is the healthiest and the taste of this age.” (Simmons 49)

As for pork, all those Brooklyn briners have influenced Simmons too.

“ To Stuff a Leg of Pork to Bake or Roast Corn [that is, cure in a salt solution: Ed.] the leg 48 hours and stuff with sausage meat and bake in a hot oven two hours and a half or roast.” (Simmons 52)

The leg is a vasty joint, so the cooking time will once again produce succulent ‘underdone’ meat consistent with the culinary parlance of our time.

“Observations” on preparing meat pie are commonsense and sound. Simmons concurs, if in tacit terms, with Croft-Cooke and Elizabeth David about the tyranny of the rigid recipe.

“All meat pies require a hotter and brisker oven than fruit pies…. As people differ in their tastes, they may alter to their wishes. And as it is difficult to ascertain with precision the small articles of spicery; every one may relish as they like, and suit their taste.” (Simmons 61)

Notwithstanding the simplicity of her style, Simmons is no primitive. She scents her apple pie with cinnamon, rosewater and lemon zest; is familiar with seven species of fresh green peas and nine of beans; and recommends parsley, pennyroyal, sage and savory along with three different kinds of thyme as “Herbs: Useful in Cookery.” “Garlicks,” however, “tho’ used by the French, are better adapted to the uses of medicine than cookery.” (Simmons 61, 43, 41, 37)

Before refrigeration, the only fresh foods were, of course, seasonal foods. More, however, was at work than practical necessity. By the middle of the nineteenth century New England supported an outsize number of cookbook writers. Under the influence of these confident authors, most notably Catharine Beecher, Lydia Maria Child and Sara Josepha Hale, the region developed a cult of ‘plainness,’ not merely arising out of frugality but also as a marker of virtue. (Perkins)

These authors arrived at their conclusions by different paths, but as the nineteenth century progressed, an ethos much like the locavore movement began to emerge. Indigenous ingredients, no longer the default for subsistence, became celebrated as evoking a self-consciously superior regional culture. Purity of flavor as an expression of regional identity also became prized in a confluence of practicality, ideology and culture. (Perkins)

Row 34 in Portsmouth, NH

The embrace by New England cooks of simple seasonal selections has accelerated in recent years, as it has everywhere else, and is most welcome. It also may be at least as appropriate in New England as anywhere else. Jeremy Sewall, owner of several Boston restaurants and the wonderful Row 34 in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, explains why.

“I don’t think there’s another region that’s more defined by its seasons. From there it flows down into what’s available and how things grow and when things are caught and harvested. In a way, the extremes of the seasons are a blessing from a cooking perspective because it’s always changing and forcing you to be on your toes.” ( Boston )

It is an insight seldom heard about New England, a region overshadowed of late in culinary terms by California and the American south.

Sewall has written one of the better recent cookbooks featuring ‘new’ New England foodways. His style is something like a more relaxed, and northern, Sean Brock. Sewall wants to stay creative in his kitchens, but like Brock also harbors a deep respect for the history of his region. “What I wanted to do” with the New England Kitchen , Sewall has said, “was tell a little bit of a story about New England’s past and present…. I also really wanted to tell the story of the farmers and the fishermen and the people that are producing the food and how that applies to the restaurants.” ( Boston )

Most dishes that emerge from The New England Kitchen are not so simple as those of Simmons, other, that is, than her rococo turtle soup, by far the longest in her little book and more complex than anything Sewall attempts.

The lineage, however, is discernable. “Cod,” as Sewall says, “the quintessential New England fish,” is simply baked beneath a scatter of shallot and lemon zest, but served with a green garlic puree. Talk about seasonal; green garlic appears for the shortest term, at least in the northeast. The sauce itself is simple enough, the white of the garlic softened in neutral oil, its greens boiled for the quickest flash, all the vegetation blasted with cream to the texture of silk. Not bad; melted butter would be even better, made with lemon juice to marry the zest.

Sewall takes similar liberties with other standards. He paints mackerel, prized in Britain but greeted with anxiety in the United States, with oil and citrus, and grills it for service on a bed of raw fennel, frisee and basil; simple enough if genre busting.

A fresh pea soup seasoned with curry lives closer to home, whether home is in Boston or London, and Sewall treats shad roe in the traditional New England manner by cooking it with bacon.

The British have fetishized the fava, which they call broad beans, and will find a pleasant rendition of them in The New England Kitchen. The beans are tossed with potato discs and scallion (Sewall Anglicizes them as spring onions), then simply dressed with Sherry vinegar. Sewall likes Sherry vinegar, a traditional British ingredient, and reaches for it much of the time.

Oyster stew is recognizable enough except for its fennel fronds, but fennel is found in some of the oldest English recipes too, but Sewall’s chowder knows no clams. That is fine; the first chowders did not use them either, and its variations are infinite, as the title of Jasper White’s 50 Chowders indicates. Sewall’s is made with bacon, corn and crab, an authentic enough Yankee triumvirate.

The dishes at Sewall’s Portsmouth restaurant reflect those described in The New England Kitchen. His style is relatively simple in contrast to the surprisingly Baroque, sometimes molecular Brock, and although New England provides his palimpsest, international influences also appear on the menu. Seafood is the star, all of it pristine.

Row 34 adheres to (a little) British tradition; fried oysters, fish and chips, a variety of smoked fish, sometimes devilled crab. New England oysters of course are a staple at the restaurant, and twenty taps dispensing craft beer include a creative selection of IPAs, porters, stouts, and a barley wine. Row 34 also serves ‘foreign’ styles for the apostate. The imaginative wine list is intriguing and reasonably priced.

Sources:

Anon., “Row 34’s Jeremy Sewall Talks His Debut Cookbook,” Boston Magazine (23 September 2014)

R. W. Apple, Jr., “New American Traditions; In a Berkeley Kitchen, A Celebration of Simplicity,” The New York Times (17 November 1999)

Jane Grigson, English Food (London 1974)

Sheila Hutchins, English Recipes and Others (London 1967)

William Kitchener, The Cook’s Oracle (London 1831)

Francis Lam, “Edna Lewis and the Black Roots of American Cooking,” The New York Times Magazine (28 October 2015)

Edna Lewis, The Taste of Country Cooking (New York 1976)

Blake Perkins, “North and south in both geography and metaphor,” www.britishfoodinamerica.com Number 25 (February 2012)

Jeremy Sewall, The New England Kitchen: Fresh Takes On Seasonal Recipes (New York [alas] 2014)

Amelia Simmons, American Cookery (Hartford 1796; facsimile edition, West Virginia Pulp and Paper Co. 1963)