An Appreciation of canned fish, including considerations of Tin Fish Gourmet by Barbara-jo McIntosh & Rust by Jonathan Waldman.

1. Sustainable is not always synonymous with fresh.

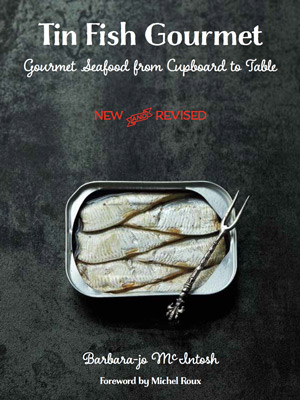

In 1998, a woman called Barbara-jo McIntosh wrote a book about cooking with canned fish. Fifteen years into the twenty-first century the concept appears prescient.

Last fall a team of London architects opened a popup restaurant in Soho called Tincan for six months that served only canned fish and cold accompaniments. It was not a joke. NPR aired a program on the place and featured it in an essay on its website. The Economist considered Tincan “a joyful paean to tinned seafood of all kinds” while in the Sunday Times the often acerbic A. A. Gill wrote “it’s fascinating and amusing and tasty, in parts. You should all go.” (www.tincanlondon.com)

Worthies like Mark Bittman and Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall champion canned seafood products with the emphatic exception of some tuna brands as healthy and sustainable.

It is a campaign Fearnley-Whittingstall has waged for a while now. Eight years ago his River Cottage Fish Book noted that an “often unsung family of fish that offers a useful set of ingredients for the cold-fish enthusiast is the kind we like to buy in tins. Everyone should have a shoal of well-chosen tinned fish in their larders.” His 2007 triumvirate of tins; sardines, tuna and mackerel, he says, ”will readily stand in for any recipe that calls for tuna--and so can certainly help in any bid to keep one’s fish shopping sustainable.” (River Cottage Fish 346)

Five years later, in 2012, Fearnley-Whittingstall had banished tuna from his tinned trinity in favor of the anchovy. He advocated the use of sardines and mackerel with increased urgency, reasoning that “the kind of small, oily fish that fit so obligingly in tins and jars are the kind of species that, if managed properly and fished responsibly, could continue to feed us sustainably well into the future…. ”

In contrast to the little fish, tuna’s “provenance is riddled with alarming environmental worries. All tuna stocks are desperately over-exploited. And it’s pretty well known now that some of the methods used to catch them can have a devastating effect on the wildlife that shares its environment…. ” Tuna nets and lines drown countless numbers of dolphins, sharks, turtles and an array of seabirds on a regular basis. (Guardian)

2. A taste for the contents of cans, or at least the fishy ones.

Those were not the concerns of McIntosh seventeen years ago. Back then her interest lay with ease and economy. She liked eating dishes based on canned fish as a child and never lost the taste. Even after operating a restaurant she says she “never forgot how to use a can opener.” (McIntosh vii)

Tin Fish Gourmet sold well enough to justify a revised edition last year. Other than a heartfelt and somewhat surprising preface from the fastidious Michel Roux (who proudly appends his “OBE’), it is not much different from the original. Unlike Fearnley-Whittingstall, McIntosh has added no nod to sustainability. The omission is a little surprising because she lives in Vancouver, British Columbia, an early bastion of the green and sustainable movements.

On the commercial plane some discussion about the sustainable properties of canned fish other than tuna might have helped with the marketing, but then McIntosh enjoys tuna. She even celebrates as comfort food something ghastly. For her, “the only drawback with the tuna casserole is that you can’t wrap it with paper and take it to school.” The enthusiasm is all the more inexplicable because McIntosh considers herself “a bit of a tuna snob” who uses only white Albacore packed in water, the worst of the canned options in terms of flavor (scant), texture (sawdust) and sustainability (endangered). (McIntosh 141)

Tin Fish Gourmet was and is hit or miss but does contain a number of good recipes. Some of them would work a lot better with fresh fish, while it is difficult to share the enthusiasm of McIntosh for some of the other canned seafood she chooses to use along with the tuna, including oysters and especially shrimp. Pasteurized oysters are a better alternative to canned, and while nobody will mistake them for fresh they work well enough for pies, puddings and stuffings. In contrast canned oysters contract into rubbery balls with a harsh and ‘fishy’ flavor. In the experience of the Editor, canned shrimp have nothing to recommend them. Their smell is bad, their flavor bad and their mucky texture worse.

Other products like smoked oysters--McIntosh blasts them into a good paste with cream cheese, lemon and spice--canned Asian eels, clams, salmon, some kippers and especially sardines are another matter.

McIntosh celebrates salmon as “the most exciting of all tinned fish” while Fearnley-Whittingstall steers shy of it, perhaps because so many bad midcentury British cooks smeared it straight from the can on airbread for Sunday supper or tea. McIntosh is mistaken about the supremacy of canned salmon but it does make a decent salad properly mixed with mayonnaise, scallions and spice.

Canned salmon also does diligent duty for fishcakes, and McIntosh prints a good version incorporating potato and peas, the traditional New England threesome served separately on the plate for Independence Day. She also likes to bake salmon loaf based on a recipe her “Granny called her own” with the addition of curry and tomato. “She was,” McIntosh tells us, “an English cook and it was a staple of her recipe files.” (McIntosh 84) The inclusion of shredded carrot and parsnip is idiosyncratic and good; skip the tomato to serve a homely supper.

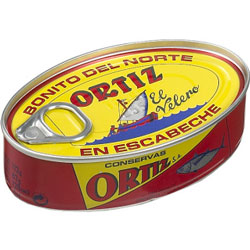

3. The little king of the canned fishes.

Then there are sardines. Canned sardines can be special, not simply expedient. Despite her celebration of salmon, McIntosh has to admit that “[i]f there is any one fish born to the tin, it’s the sardine.” (McIntosh 109) As with tuna, however, she picks the wrong product by insisting on sardines packed in water instead of the essential olive oil.

As Jane Grigson points out, “[s]ardines were the first fish to be canned--in the 1820s.” McIntosh maintains it was almost a century before anybody thought to preserve, for example, salmon the same way. (Grigson 332; McIntosh 79)

The original reason for canning sardines or anything else was expedience. “Since the sardine is seasonal, arriving in incalculable quantities, the problem was, in the past, preservation of the catch.” A Lorient woman had decided to fry sardines quickly in olive oil and submerge them under more of it in jars to prevent oxidation and spoilage. (Grigson 333)

Cans quickly replaced jars and an unintended alchemy ensued; “the methods of canning have produced not just a poor substitute (like canned crab and lobster) but something worth eating in its own right.” Just as canned peas amount to an entirely different substance from fresh, canned sardines, especially the French ones aged for a year or more before release, have nearly nothing to do with fresh. They carry a more complex and beguiling flavor. (Grigson 333)

4. Cans are complicated…

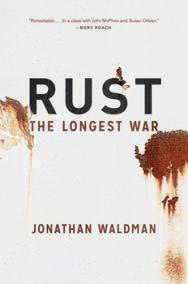

Cans more generally are as miraculous as these contents. As Jonathan Waldman explains in Rust: The Longest War, the technology required to manufacture the ubiquitous container is by no means mundane. Almost every substance requires a different lining to prevent it from spoiling, corroding the can itself or even causing an explosion. Every substance presents a different problem for the canner and some have stymied the industry for over a century. The first beer can, for example, did not appear until 1935, following decades of trial and error. (Waldman 93)

5… and so is their history.

According to Waldman, the first cans were “developed by an Englishman in 1810,” but that is not quite right. (Waldman 91) It is a bit of a surprise that so little has been written about the origin and history of canning, and that one of the better sources turns out to be the BBC. To write “The story of how the tin can nearly wasn’t” for the BBC Magazine, Tom Geoghegan did better research than Waldman.

The ‘Englishman in 1810’ refers to a merchant, Peter Durand, who obtained a patent in Britain “to preserve food using tinplated cans.” The patent itself recites that it was “an invention communicated to him by a certain foreigner residing abroad.” Geoghegan in turn cites research by Norman Cowell indicating that a French inventor called Phillipe de Girard had retained Durand as his agent to obtain the patent. (Geoghegan 5)

De Girard “had been making regular visits to the Royal Society to test his canned foods on its members.” Sir Charles Blagden, a fellow of the society, had kept a diary of its activities, including the visits of de Girard. From the entry for 28 January 1811:

“M Girard came and brought his preserved foods. We tasted the milk and the broth and the roasted meat. All good but the milk was yellow and had a bad taste. The broth had been kept since August last, he said. The milk and beef six weeks. He had a phial of large size, milk, broth and gravy in tin kettle [sic] with covers soldered on…. His patent is taken out in the name Durand.” (Geoghegan 6)

The Napoleonic Wars raged on, so as the citizen of a foreign belligerent de Girard could not acquire the patent himself. He had, however, taken his creations to London, and taken out a British patent, for good reasons. Neither money nor patent was available to him in France. Cowell explains that in contrast

“England was entrepreneurial, there was venture capital. People were prepared to take a risk and go bankrupt. In France if someone had a good idea they took it to the Academie Franciase and if they thought it was a good idea they might get a ‘pourboire’ [tip]” (Geoghegan 6)

He may also have been following the market, for British diners were more amenable to the notion of preserved food in general. As Sue Shepherd notes, during the course of the eighteenth century “French cookery books, unlike the English, had very few fruit bottling recipes,” or, she might have added, nearly as many recipes for bottling or pickling anything else, or for potting all manner of fish, meat and even mushrooms under a protective seal of clarified butter. (Shepherd 229)

It is unclear how Durand took complete control of the patent; perhaps he bought the rights from de Girard. It is clear, however, that Durand did not develop anything. Instead he “sold the patent to engineer Bryan Donkin for £1,000 and he disappears from the story” toting his hefty fee. (Geoghegan 7)

Donkin was a pragmatic inventor and entrepreneur. Along with money from a partner he plowed his profits from a papermaking machine--itself revolutionary--into the problem of preservation. For two years he and another partner, John Gamble, experimented to transform de Girard’s methodology for commercial production. They built a factory in Bermondsey for the purpose.

Along with so many of his British contemporaries, Donkin looked to the sea. Maritime conditions presented their own particular problems with corrosion. The twofold solution Donkin adopted sounds simple and would prove enduring:

“Tins for sea stores were liberally coated with red lead paint to protect them from seawater, which would corrode the tin. Each tin lid was fitted with a ring for carrying and for hanging them up.” (Shepherd 243-44)

Hanging the cans saved scarce shipboard space and also discouraged corrosion by keeping the cans from contact with damp decking. Red lead prevailed as a preeminent marine anticorrosive for over a century. Its color became particularly associated with salmon, and many canned brands retain their traditional deep red labels, while the United States Navy specified swathes of red lead on warships past the end of the Second World War.

These early cans were big, ranging in weight from two to seventeen pounds. (Shepherd 244) They contained beef, carrots, mutton, parsnips or soup. In 1814 the Royal Navy alone ordered almost 3,000 pounds of Donkin’s canned food; by 1821 its order had grown more than threefold. (Geoghegan 2, 7, 9)

6. Now I’m walking from New Orleans….

Waldman asserts that the term ‘can’ originated with “a Londoner who sailed to Boston named William Underwood,” but does not disclose when he, or rather “one of his bookkeepers shortened the word canister--from the Greek kanastron, ‘a basket of reeds’--to can.” (Waldman 91) Once again, Waldman has not quite got things right, casting further doubt on his general reliability, a doubt difficult to allay because Rust carries neither footnotes nor bibliography.

Underwood, whose Deviled Ham remains a Yankee staple and whose name also represents the oldest extant American trademark for food, did not sail to Boston: He walked there. (P. Smith; A. Smith 91) As Andrew Smith explains in The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink:

“In the United States commercial bottling operations did not commence until the arrival of English canners. The first was William Underwood, an English pickler, who landed in New Orleans in 1817 and decided to trek across the country on foot. Two years later he arrived in Boston, where he launched the firm later known as the William Underwood Company.” (A. Smith 91)

Underwood had a knack for marketing and his chicanery would impress any archetypal adman from the 1960s. Early cans produced in Boston for export bore the legend ‘Made in England,’ “presumably,” according to Sue Shepherd, “to make the consumer feel it was a well-tried product from the old country and not something suspect from the new.” (Shepherd 245)

As Underwood understood, it is a paradox of the canning process that the product requires isolation from the package itself. Tin cans never have been made entirely or even predominantly of tin; it was the first coating that protected the contents of the can from the steel can itself. Tin, however, did not work for every product. It bleached beets, cherries and strawberries, turned beans black and corroded on contact with ham, orange juice, pickles and sauerkraut. (Waldman 92-93)

The first solution to the problems encountered in attempting to can these products was to cover the tin coating with different enamels in different thicknesses for different things. Early success stories based on enamel include applesauce, tomatoes and of course our sardines. As it turned out, beer required two coats of different enamels to keep it and its can sound.

7. Can we cook the contents of this can?

Back to the contents rather than their container, Mrs. Grigson sounds a warning for her readers. “You can do a number of things with canned sardines, but none of the recipes that involves heating them is to be recommended. There is always another fish--herring or anchovy--which would give a better result.” (Grigson 334)

She was echoing the “stern words of a director at Phillipe et Canard” in 1962, then the most venerable and biggest sardine canner in Nantes, epicenter of the French--it must be said best--sardine processing industry. In an interview, he gave Elizabeth David a chance to indulge one of her favorite tropes, the bashing of British foodways. “‘Our fine sardines,’ he said,

‘must not be cooked. At an English meal I was given hot sardines, on cold toast. It was most strange. They were my sardines and I could not recognize them. The taste had become coarse…. please, no shock treatment.’” (David 277)

McIntosh, Roux and Fearnley-Whittingstall demur. She likes sardines (the watered ones) cooked in a tomato curry for toast and also roasts them with leek, lemon and vinegar; neither preparation would put your table to shame.

Although McIntosh does not say so, Roux is an aficionado of canned food and bottled sauce. That is something of a surprise, because he is the eminence grise of Le Gavroche in London, where most things from the can and commercial sauces are infra dig. Roux likes to make sardine and mustard sandwiches in the manner of grilled cheese topped with an egg and spattered with Worcestershire. In addition to the sardines (“We all love tinned sardines and I am no different…. “) Roux keeps cans of anchovies, cod liver, mackerel, patés and tapenades. (Weekend FT)

Fearnley-Whittingstall likes the sardine omelet he confers his daughter credit for ‘inventing;’ just start an omelet in the usual way, throw broken sardines over the bubbly disc for an instant and fold it over.

It also is possible to devil sardines without rendering them ‘coarse,’ although they will be assertive. The key, as with any application of heat to the little fish, is the briefest touch of flame. In The Master Book of Fish from 1949, Henry Smith provides a simple and successful recipe:

“Lay the sardines in a shallow baking tin and brush gently with prepared mustard mixed with Worcestershire Sauce. Flash under the grill. Sprinkle with paprika and serve on toast.” (Smith 158; for Americans ‘the grill’ is the broiler)

The heat of the mustard and bite of the Worcestershire marry well with the strong flavor of the fish, and a smear of Smith’s mixture on sardines uncooked is pretty pleasant too.

Mrs. Grigson does allow some further processing of canned sardines, at least for products of lesser quality: “Left-over sardines, or not-quite-the-best sardines make an admirable fish paste if you mash them with unsalted butter.” The best sardines, she might have added, do even better for paste, but then Mrs. Grigson likes them like the director, straight from their can “with decent bread, fine butter and some lemon, or as part of a mixed first course.” (Grigson 334) He also would have allowed the addition of cayenne, although hot sauce is superior, and nothing more. Sardines, it seems, have earned the same esteem as oysters. (David 277)

Recipes using canned goods appear in the practical.

Sources:

Norman Cowell, An Investigation of Early Methods of Food Preservation by Heat, unpubl. PhD thesis, University of Reading (1994)

Elizabeth David, An Omelette and a Glass of Wine (New York 1985)

Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, The River Cottage Fish Book (London 2007);

“Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall’s fish recipes,” www.guardian.com (13 April 2012) (accessed 19 April 2015)

Tom Geoghegan, “The story of how the tin can nearly wasn’t,” BBC News Magazine, www.bbc.com/news/magazine-21689069 (21 April 2013) (accessed 23 April 2013)

Jane Grigson, Jane Grigson’s Fish Book (London 1993)

Barbara-jo McIntosh, Tin Fish Gourmet: Great Seafood from Cupboard to Table (Vancouver BC 1998)

Michel Roux et al., “Kitchen cabinets,” Weekend FT (4-5 April 2015)

Sue Shepherd, Pickled, Potted, and Canned: How the Art and Science of Food Preserving Changed the World (New York 2000)

Andrew Smith, “Canning and Bottling,” The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink (Oxford 2007)

Henry Smith, The Master Book of Fish (London 1949)

Peter Smith, “Underwood’s Deviled Ham: The Oldest Trademark Still in Use,” www.smithsonianmag.com (March 2012) (accessed 26 April 2015)