British food between the wars, in city, country & neither place, featuring the habits culinary, artistic & amorous of Bloomsbury.

1.A false prophet.

In her Book of English Food , Arabella Boxer argues that “between the two world wars English food underwent a brief flowering that seems to have gone unremarked at the time, and later passed into oblivion.” In her telling the trend did not get too far:

“Such things take time to reach all levels of society, and this one hardly had time to spread beyond the sophisticated world in London and the south before war was declared, and the country was plunged into austerity.”

Boxer is referring to the imposition of rationing by the War Cabinet in 1939. With the advent of that culinary cataclysm, and rage for Mediterranean food that Elizabeth David provoked in 1950, “our own English food was forgotten.” (Boxer 1)

Christopher Driver believes otherwise and without equivocation: The interwar attempt to revive English cuisine was a provincial enterprise confined to small segments of the middle classes and rural gentry, and went unnoticed by the sophisticates Boxer cites. Despite the tireless work of Florence White and other “rescue archeologists,” these “stirrings of cultural patriotism or catholicity exerted little or no influence on metropolitan cooking,” where “the kitchens of London hotels and restaurants were still dominated by French and more particularly Italian” cooks. (Driver 9,10) It therefore, as Alexandra Harris warns in Romantic Moderns , “would be wrong to make the recuperation of English cooking sound clear-cut.” (Harris 122)

2. No British food please, we’re progressives.

Extant sources tilt toward Driver’s perspective. As Boxer herself observes, no ‘flowering of English food’ was remarked upon between the wars. White for one had feared for its survival. “We had,” she lamented, “the finest cookery in the world but it had been nearly lost through neglect.” (White flyleaf)

Whether concocted by French or Italian chefs, a certain style of ‘French’ food remained firmly in fashion. If nobody in France might have recognized these dishes as particularly French, nobody anywhere would have considered them English either.

Nor would it appear that “the sophisticated world in London” was smitten with English food. As the more cosmopolitan crowd by a city mile, Bloomsbury should have been the segment of society likelier than the middle class cooks consulted by White or the hunting, shooting and fishing crowd out in the shires to accept a novel concept, in this case, and ironically enough, a jaunt back to the British culinary future.

With few exceptions they did no such thing.

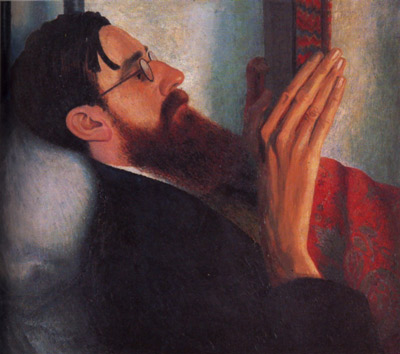

“Bloomsbury turned to Europe for inspiration,”, according to Harris, “not to the dishes of Escoffier et al., but to the rural peasant traditions that were still going strong.” The celebrated art critic Roger Fry “was devoted to traditional Provençal cookery.” He along with Vanessa Bell, Virginia Woolf “and their friends all sent joyous letters from France recording long lunches, long dinners, fresh seafood, rich stews, ripe cheeses and excellent wine.” (Harris 120)

“Comfort did not rank high in Bloomsbury houses (though beauty did), but Frances Partridge recalled “there would be good French cooking, wine at most meals, home-made bread and jams (Virginia was good at making both). (Partridge)

“Despite a profound ignorance of all aspects of food preparation,” Jans Ondaatje Rolls maintains in The Bloomsbury Cookbook that

“the members of the Bloomsbury Group were the ‘foodies’ of their day: enthusiastic about tasty, ‘unfussy’ dishes and passionate about Côte de Provence wines and the heady flavours of southern French cuisine…. Their servants were sent on cooking courses and provided with the latest ‘French-style’ cookery books, sometimes with inspired results.” (Ondaatje Rolls 14)

According to Ondaatje Rolls, Clive Bell, his wife Vanessa and her sister Virginia Woolf disdained English food. It “was unadventurous, bland and overcooked, but to eat foreign foods and wines [sic] was to be enraptured by a symphony of flavours and desires.” (Ondaatje Rolls 203)

Ondaatje Rolls recounts the descriptions of dishes and recipes she found from cookbooks kept on the shelves of Bloomsbury kitchens and in the circle’s manuscripts, notations and letters.

Vanessa Bell’s beloved servant Grace Germany, for example, “became an excellent cook, taking inspiration from her visits to France and from the finest cookbooks of her day.” French cookbooks kept in the Bell kitchens at Gordon Square and Charleston included A Second Helping and A Finer Cooking , both by the great Marcel Boulestin, along with Chester’s French Cooking for English Homes .

Virginia Woolf had no patience for English food. Two of her cultured characters concur.

“What passes for cookery in England is an abomination…. It is putting cabbages in water. It is roasting meat until it is like leather. It is cutting the delicious skins off vegetables…. And the waste… a whole French family could live on what an English cook throws away.” (151-52)

When Ambrose Heath, who later would champion traditional English foods, paid a double tribute to Boulestin and Bloomsbury in his Good Food from 1932, he chose the decidedly French Boeuf en Daube, a dish described by Woolf in the famous dinner scene from To the Lighthouse. (Heath 184; Harris 121)

Yet as Rowley Leigh, proprietor and chef at Le Café Anglais in London, maintains, “Virginia Woolf may have been a gourmet but she was no cook.” He quotes part of the Lighthouse passage to prove his point that it “is, quite simply, full of howlers:”

“Everything depended upon things being served up to the precise moment they were ready. The beef, the bay leaf, and the wine--all must be done to a turn. To keep it waiting was out of the question.” ( To the Lighthouse 121)

And so to Leigh in rebuttal:

“How a bay leaf can be ‘done to a turn’ is a conundrum at best: it is there to give aroma and to be eventually discarded. The beef, and wine for that matter, are cooked for a very long time; the notion that any precision is required is erroneous. One of the many good things about a daube of beef is that it can wait around without coming to any harm whatsoever.” (Leigh)

It is after all a stew, and Leigh might have added that doing something to a turn refers to the eighteenth century practice of roasting meat on a turnspit before an open flame. To ensure even cooking and prevent overcooking the great joints of beef did require touch and precision.

Woolf herself did not even have a recipe for the daube she describes, so Ondaatje Rolls substitutes one of her own.

The Bloomsbury Cookbook recounts recipes not only from France but from all around the Mediterranean rim, throughout central and eastern Europe, even as far afield as the American south. Dora Carrington along other members of the set learned to cook after the First World War had disrupted domestic life, not least by creating a scarcity of domestics including cooks, prepared an “indescribably grand” dinner of Italian dishes for Helen Anrep at Ham Spray in 1925; chicken sauced with tomato and fennel accompanied by a risotto made with almonds, onions and pimiento. (Ondaatje Rolls 165)

3. Trouble in Bloomsbury.

Unfortunately Ondaatje Rolls is an uneven, at times even slovenly author whose work would have appalled the more meticulous members of the circle whose domestic arrangements she addresses.

Who, for example, is Helen Anrep? Given the talents of the group, she might have any number of claims to Bloomsbury fame. Was she an engraver, painter or sculptor? Novelist, historian or publisher? Art critic, economist or political theorist? Did she publish her memoirs? Ondaatje Rolls strings her reader along. In a series of cryptic references, she discloses that Anrep became a good cook, left her husband, and visited both Lady Ottoline Morell and the Ham Spray ménage.

Finally, 228 pages into The Bloomsbury Cookbook , we learn that Anrep became Roger Fry’s lover, and the information inexplicably gets repeated three pages later. After another twenty pages, Ondaatje Rolls undermines any basis for discussing her at all. “Helen Anrep,” it turns out, “was not an artist, a writer or an intellectual…. ” (Ondaatje Rolls 251) Her inclusion in the Cookbook is entirely expedient: Anrep’s clippings of recipes survive, and Ondaatje Rolls reproduces twenty-five of them without discussing whether Anrep served any of the dishes to anyone connected with Bloomsbury.

The awkward structure shares its pages with inexplicable errors. It would have required the most rudimentary research, for example, to realize that it is always the Royal Navy or British Navy, never the ‘Royal British Navy.’

Some passages are nearly incomprehensible, while redundancy abounds:

“This frugal soup recipe from a First World War cookery book will satisfy unpretentious bohemian tastes, and maybe even hunger…. A dash of sherry will enhance the flavour, and will render the soup even more palatable.” (Ondaatje Rolls 64)

The reference to a cookbook from World War One is symptomatic of another problem, for it, like much in The Bloomsbury Cookbook , has nothing to do with the circle. Ondaatje Rolls blithely admits that “[n]ot all recipes relate to Bloomsbury directly. Many have been sourced from contemporaneous cookbooks and some are my own Bloomsbury-inspired creations.” (Rolls 18) One of these ‘contemporaneous’ sources, Lobscouse and Spotted Dog , dates to 1997 . It is “the gastronomic companion to Patrick O’Brien’s Aubrey-Maturin series of novels” about the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic Wars. (Ondaatje Rolls 290)

This lack of authenticity is both unfortunate and unnecessary, unfortunate because Ondaatje Rolls does not always indicate which recipes the cooks of Bloomsbury actually used and which ones they did not, unnecessary because the group documented everything it did.

Many of their kitchen manuscripts survive and so do records of the cookbooks they bought; in some cases so do their own copies of the books. As Ondaatje Rolls indicates, more than “170 original Bloomsbury recipes have been included in The Bloomsbury Cookbook .” (Ondaatje Rolls 14) It would have been stronger without the padding, although the proliferation of pictures, sometimes unrelated to text, is most welcome.

The effort to shoehorn so many unrelated recipes into the Bloomsbury canon results in some strained analogies and specious associations rendered in awkward prose. A discussion of Thoby Stephen is but one example. In his remembrance of Stephen, the brother of Vanessa Bell and Virginia Woolf, her husband Leonard described “his monolithic character, his monolithic common sense, his monumental judgments.” (Ondaatje Rolls 31)

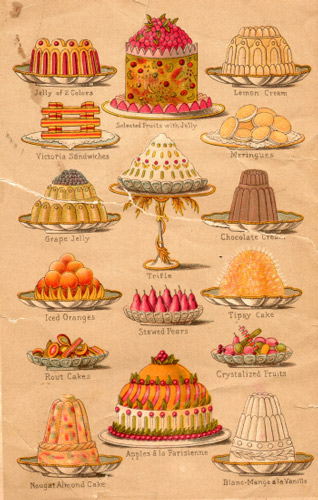

Thoby Stephen was twelve years old in 1895 when Virginia described his birthday party, which Ondaatje Rolls has taken as a vehicle to reproduce the recipe from an 1892 edition of Beeton’s Book of Household Management for a “monolithic Marble Cake.” Apparently it does not trouble her that the passage about the party she quotes does not mention cake; the original edition of Mrs. Beeton appeared more than three decades earlier than 1895; its recipe has no known tie to the children’s parents, who were not members of the Bloomsbury group that did not exist when they arranged the party; and The Book does not describe the cake as ‘monolithic,’ perhaps because in fact it alternates dark and white sponge. (Ondaatje Rolls 31)

The resort to Isabella Beeton is all the more dispiriting because her regimented recipes were, as Harris recognizes, antithetical to the spirit of Bloomsbury. “Bean stews, impromptu gatherings, no more gongs: here was a rebellion against the orderly ranks of dressed-up dishes like those in Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management (1861). Looking with an untrained eye at the illustrations in that Victorian gospel, it is easy to mistake a Chartreuse of Partridges [Editor’s note: Itself a vaguely French preparation] for an iced cream cake.” (Harris 121)

A bigger problem confronts the hopeful cook: Ondaatje Rolls has not bothered to prepare many of the recipes, whatever their origin. She has cooked some of them but neglected to identify which ones; “testing was not systematic and the results cannot be guaranteed. For a reader planning to make any of these dishes for a dinner party or the like, I strongly recommend a dry run beforehand!” (Ondaatje Rolls 14)

4. The unwarranted mystery of Bloomsbury.

Other than commenting on the free-spirited genius of its members, Ondaatje Rolls declines to discuss how Bloomsbury was intellectually distinctive. To be fair, it has been discussed to death, and her brief lies in the kitchen rather than the realm of ideas. Still it would be nice to know why Ondaatje Rolls celebrates her subject and whether or not its foodways had much to do with its ethos.

“Its philosophical cornerstone,” according to Regina Marler, “was personal liberty, especially sexual liberty and freedom of expression, coupled with an emphasis on personal relationships and an appreciation for the arts.” (Marler 7)

Marler’s description is fine as far as it goes--Antonin Scalia will be apoplectic--but does not capture the drama and nuance that define the group. Carrington considered the “quintessence” of it as “a marvelous combination of the Highest intelligence, & appreciation of Literature combined with a lean humour & tremendous affection. They gave it backwards and forwards to each other like shuttlecocks only the shuttlecocks multiplied as they flew in the air.” (Hill 31)

One of the better descriptions of Bloomsbury’s intellectual foundation belongs to Irvin Ehrenpreis. It derived, he explains, from the philosophy of G. E. Moore, a don who exerted an extraordinary influence on the men who formed the original circle in the hermetic hothouse of Edwardian Cambridge. “Moore’s philosophy,” Ehrenpreis explains,

“combines several distinct elements: a methodical insistence that one analyze and carefully define one’s meanings (‘What exactly do you mean?’); an acceptance of commonly followed rules of practical morality--don’t kill, don’t steal, etc…; but above all, a definition of the ultimate, intrinsic goods of this life as ‘states of mind’ focused on love and friendship, beauty in nature and art, and the search for true knowledge.” (Ehrenpreis)

The cast of this philosophy was admirably secular: “Moore made deliberate attacks on Christian ethics, chastity, love of God, the idea of heaven.” In the circumstances the practical fallout could be culturally radical during the first half of the twentieth century. “The mysteries of the earth, of the body, of love, easily survived in Bloomsbury. The mysteries of church and state, of money and sex, did not. In these departments reticence seemed opposed to health.” (Ehrenpreis)

This outlook springs straight from the tradition of English empiricism. Moore recognized that his rules of practical morality were not much good “when, as often happens, a man must chose among several good courses;” then “he should prefer what he strongly desires, what concerns him directly, and what he can get fast.” In practical terms, and Moore’s philosophy stressed the practical over the aspirational, anyone “should reject greater goods that he cannot appreciate, extended beneficence that he cannot persist in, and those goods he would have to wait a long time for.” (Ehrenpreis)

These precepts leave a lot of room for interpretation, and Bloomsbury interpreted them to exalt honesty and candor over manners and discretion, and to reject not just jealousy but also monogamy. Judgment of others, however, was equally suspect. When Mark Gertler struck the feeble Strachey in a rage over his strange relationship with Carrington (“anything more cinematographic,” wrote Strachey, “can hardly be imagined”), he mused with sympathy that jealousy must be a painful emotion for anyone who suffered from the condition. (Annan)

Strachey shared his conviction with the entire circle: In Bloomsbury deception or even just dishonesty was the only betrayal. If two or more people shared an urgent need, for sex or any other form of expression, forbearance fueled nothing but frustration and therefore failed to serve any legitimate end. Such, for Bloomsbury, was the reality of the human condition. As Ehrenpreis understands, “[l]arge doses of reality can only be compounded in an air of extreme tolerance; and this of course is quintessentially the atmosphere of Bloomsbury.” (Ehrenpreis)

The price, however, was high. The sexual entanglements, brutal exchange of ideas and information along with, paradoxically, the unwillingness of the tangled crowd to abandon the friendship of anyone following heartbreak or even betrayal, kept the circle in a condition of relentless turmoil. Ehrenpreis again:

“Tolerance sometimes means self-torment. Easy exposure can be a screen for sickening prurience…. We now know what humiliations and defeats these pioneers opened themselves to with their reliance on reason and good humor. We know how much compassion worked behind their wit. We also know the degree of courage, the lack of self-pity, with which they underwent their various ordeals.” (Ehrenpreis)

It is hard to imagine how, in this perfervid emotional maelstrom, any of them got anything done. But they more than managed. Fry the art critic, Keynes the economist and Strachey the historian alone were, in the accurate estimation of Ehrenpreis, not just an unstable erotic triangle but also “men of genius” who transformed twentieth century thought. The larger circle also left an astonishing legacy. According to Ehrenpreis, “the Bloomsbury direction, with its playfulness, tolerance, and honesty, its respect for human ties, its suspicion of authority, connects us to the greatest humanists, Rabelais, More, and especially Erasmus.” (Ehrenpreis)

Here Ehrenpreis loses his way, for as Hilary Mantel has reminded us, More in fact was a fanatic proud to immolate anyone who disagreed with his hideous dogma. Even so, the elevation of Bloomsbury to humanist paradigm and even to the heights of Erasmus is fair enough.

The linkage of Bloomsbury to Rabelais is particularly appropriate in the culinary context. As one scholar maintains, “for Rabelais food, France and the French language go together.” (Higginson 172) Foodways, he believes, lie at the heart of culture, and whether or not the denizens of Bloomsbury agreed on its centrality, they would concur that paying serious attention to the table is a prominent pleasure, and pleasure to them amounted to a human right.

5. Trouble in Bloomsbury, and in particular at Ham Spray.

Notwithstanding its flaws, The Bloomsbury Cookbook does develop some interesting anecdotes about those London aesthetes who, in Dorothy Parker’s typically trenchant terms, lived in squares, painted in circles and loved in triangles.

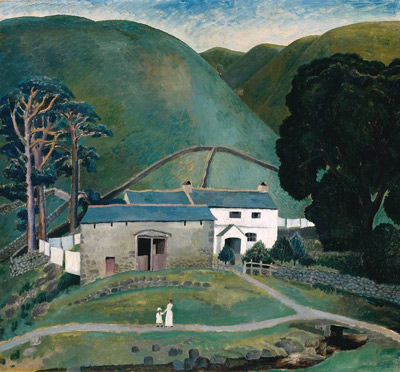

Another one of these triangles evolved into an unstable series of many sided geometries at Ham Spray, the Wiltshire retreat of Lytton Strachey, Ralph Partridge and Carrington. It was, as Carrington described Tidmarsh Mill before it, “a communal nest for breakers of the law.” ( Carrington 118)

She is an extraordinary figure even by Bloomsbury standards and even discounting the eccentricity of her erotic arrangements. Unlike all the original members of the circle, Carrington did not attend Cambridge but graduated from the Slade, where she radiated the elusive magnetism that would beguile acquaintances for the rest of her life. There she dropped the ‘Dora,’ cropped her hair, adopted frumpish dress and became the center of the Slade social swirl. Fellow painters and students Mark Gertler, Paul Nash and others fell hard for her.

6. An interlude with Dora Carrington (but don’t call her Dora).

Carrington was complicated. A reticent and often strange demeanor did not disguise her disturbing instability.

A disturbing instability

A sympathetic Julia Strachey considered Carrington in her thirties something of a witch,

“a changeling…. From a distance she looked a young creature… but if one came closer… one saw age scored around her eyes--and something, surely, a bit worse than that--a sort of illness, bodily or mental, which sat so oddly on so unspoilt a little face, with its healthy pear-blossom complexion.” (Strachey 119)

Julia, Lytton Strachey’s cousin and years younger than Carrington, was her great unrequited love. They spent a lot of time together and Julia came to believe that Carrington

“spiritually existed in the very teeth of some sort of spiritual whirlwind, too near whose path she had chosen to stray, and in whose arms, ice-pinnacled and wuthering, she had built her own nest, living there always in readiness, any instant, to cast herself over the edge altogether and be done with it all.” (Strachey 119)

Carrington contained childlike multitudes on a scale worthy of Whitman. Virginia Woolf, frequently waspish and even decidedly unkind in her diary, wrote that Carrington “is odd from her mixture of impulse & self consciousness. I wonder sometimes what she’s at: so eager to please, conciliatory, restless, & active… but she is such a bustling eager creature, so red & solid, & at the same time inquisitive, that one can’t help liking her.” (Bell vol. 1 153)

The rest of Bloomsbury echoes Woolf’s appraisal. “By all accounts,” writes Gabriele Annan, “and we have many of them from members of Carrington’s gossipy, analytical, and articulate circle--she was a naïve, fey, reckless, clumsy, irrational and unconfident creature. Droves of men fell in love with her combination of milkmaid innocence and kooky mystery.” (Annan)

One of them, Gerald Brenan, noted that “she was not physically attractive to most men, perhaps because she did not radiate sex,” but reminisced from experience that “if anyone fell in love with her it took him many years to get her out of his system. “The reason for this,” he explained, “lay in her character.”

Not in the least unattractive

Not in the least unattractive

Brenan’s 1971 eulogy in The New York Review of Books --halfheartedly disguised as a review of her letters compiled by his rival, David Garnett--floats on an undercurrent of palpable grief four decades after her death. Brenan considered her correspondence “surely the best letters to have been published in England in this century” and his description of Carrington is generous, tender, evocative:

“She was immensely alive with a hidden life of her own, though this was partly masked by her quiet and subdued manner. Her eyes, moving restlessly about the room, were an index of her mind, which was continuously being caught by new objects. Her mood too changed all the time. Whatever she felt she felt with the greatest intensity. Each new impression erased the last one so that when she looked into herself, she was aware of a welter of conflicting feelings which she could not organize.” (Brenan)

“Thus,” Brenan explains,

“she was continuously being torn between her desire to be alone and paint, to work in the garden, to go to parties and see people, or to visit her lover, or perhaps not visit him but instead write him a letter. Suddenly the desire to do this or that would come over her and she had to follow it, and then she would change her mind and do something else. That is, she had the lack of coordination of a child, together with a child’s freshness and immediacy of vision.” (Brenan)

If, however, Carrington could be feckless, she was anything but irresolute in her relationships:

“Yet though changeable in her moods she was constant in her affections. She never stopped caring for anyone she had once loved and when the relation began to go wrong as, owing to the strain set up by her complicated life and her erratic temperament, it was continually doing, she made the greatest efforts to renew it and keep it alive. She never willingly gave up anyone.” (Brenan)

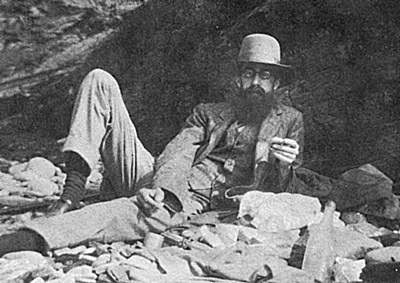

Carrington’s life was complicated more than anything else by the intensity of her infatuation with Strachey. He felt something similar toward her, if not necessarily love then a deep gratitude for her unconditional devotion.

Their bond endured affairs on both sides, long interludes apart, sickness and sexual dysfunction. When Strachey died of undiagnosed stomach cancer, Carrington killed herself in despair. She was only thirty-nine.

The couple was weird even by the standards of Bloomsbury. “Both together and apart they were stared at in the street. Carrington’s hair attracted hostile yells and Lytton’s unfashionable beard provoked ‘goat’ bleatings.” (Hill 31)

The circle itself was uncharacteristically aghast and even disapproving at the inception of the odd affair but people adapt so after a time they accepted the arrangement. (Hill 31) After all, the self-consciously tolerant Bloomsbury set adapted better than most.

Strachey was seventeen years senior, a long skeletal wraith with “ridiculously crane-like limbs” who looked and was learned almost to the point of parody. (Hill 32)

Tiny Carrington, “a constant nymph,” considered herself unlettered and loved him for introducing her to history and literature. (Hill 29) He was frail, a faint physical gust; she was every bit as robust as Virginia Woolf’s description of her and did not shrink from shooting rabbits.

They attempted sex to no avail, and apparently either told Keynes about their trouble or attempted to conceal their liaison from him depending on who you trust. Carrington sent a letter attaching a poem in Strachey’s handwriting that she illustrated, appropriately given the language of the poem, with a languid cat:

“When I’m winding up the toy

Of a pretty little boy

--Thank you, I can manage pretty well

But how to set about

To make a pussy pout

That is more than I can tell.” ( Compare Gerzina 90 with Carrington 37n.1)

Their incompatibility in bed was inevitable. Neither of them really liked straight sex. Strachey was gay, and initially agreed to the ménage at Ham Spray only to pursue Partridge. Carrington found intercourse “vulgar” if revelatory. According to Gretchen Gerzina, her biographer, “she found that sex improved her understanding of literature,” or at least poetry. “It,” Carrington wrote to Gertler after finally consenting to “copulate” (a favored word in Bloomsbury) with him for her first sexual experience, “certainly is a necessity if one wants to understand the best poets.” (Gerzina 100, 101) In the same letter, however, she insisted on rationing relations to no more than three times a month.

The happy couple

7. A painter discouraged and neglected.

Painting, Carrington also informed the unfortunate Gertler, was better than sex. And she wrote to Strachey: “Do you know I am never so happy as when I can paint.” ( Carrington 258) According to Gabriele Annan, Carrington said she painted when she was happy, and the process of painting made her happier. (Annan)

Unlike sex, she was good at it, at woodcuts, at interior design and at drawing. The paintings and woodcuts share an emphatic, muscular style but the subjects of her portraits invariably appear contemplative. While some of the pictures look like they bear a vague expressionist cast, none of them looks the least bit French.

Much of her work derives from the English vernacular, and she was as happy to paint wooden signs for public houses or the bedrooms of her friends as to work on canvas.

A lot of the paintings owe a debt to this decorative streak but, at least to this observer, do not suffer for that. Some of her later work, painted on glass, incorporates foil candy wrappers and bears a closer connection to craft than to art. None of this work, however, lacks atmosphere or charm and much of it stands with the best of its time.

Jane Hill, who curated an exhibition of Carrington’s work for the Barbican in 1995, maintains that her “life was almost entirely visual.” (Hill 33) The claim, however, reflects Hill’s own interest more than historical reality. Her judgment is hard to reconcile with the way Carrington spent her time, her happy hours in garden, stillroom and kitchen, her devotion to serving Strachey, the enduring fascination with life on the English land.

Carrington was handy. She could make the wry comment that she knew better than anyone in England the mechanics of the yellow car she loved to drive, and found solace in sailing and the sea.

Carrington’s vision of the Labrador coast

8. A life in letters.

More than any other thing, Carrington wrote, for hours each day, producing endless letters to friends and lovers. Her spelling was bad but she did not care, and many of her ‘mistakes’ are more evocative of her moods than anything grammatical might have been.

In part her prodigious output resulted from her antipathy to the telephone but a deeper motivation played a part. Her correspondence, she believed, exposed “the nakedness of the female’s mind.” (Hill 33, 35, 39) The process of composing her correspondence became a means for Carrington to order her world and bind people to her.

Brenan is not alone in his appraisal of their value. Virginia Woolf, who as noted could be most unkind, always enjoyed a letter from Carrington, “tearing like a may-fly up and down the pages.” They were, thought Woolf, “ideal in the way of hands,” whatever that means, and “completely unlike anything else in the habitable world.” ( Carrington 215; Bell vol. 5 7, vol. 2 596)

Not that the letters do not demonstrate an acute power of observation and striking visual verve. Ever the art student, Carrington always wrote with purple or green ink and illustrated them with drawings as whimsical as her paintings can appear contemplative. Hill’s description of them as “vivid, painterly, illuminated letters” is good. (Hill 33)

Despite all her talent, Carrington neither exhibited her paintings nor published any writing. In 1976, the director of the Tate described Carrington as “the most neglected serious painter of her time.” (Hill 7) The reticence stemmed in part from the other brilliant but in this respect myopic inhabitants of Ham Spray. Although Gerzina demurs, other historians of Bloomsbury believe that neither Strachey nor Partridge, who anyway had no appreciation for anything visual, considered her work worthy of promotion when they considered it at all.

Other acquaintances, who did appreciate painting and made a celebrated reputation from it, failed to appreciate Carrington’s work. Neither Roger Fry “nor Clive Bell, enormously influential in British art circles, used his position as critic to forward her career.” (Gerzina 68)

The behavior of Fry is least forgivable. Gerzina believes he wrecked her confidence, although her assertion that Carrington grew disillusioned with her work stands at odds with other accounts, including her own. After Carrington asked him “for encouragement and advice” sometime around 1916,

“Fry discouraged her from a career as a serious artist, despite her obvious talent and success at the Slade. (Frances Partridge later called this ‘just obtuseness on his part.’) Although she would continue to paint throughout her life, she never again did so with confidence, and from then on satisfaction with her work eluded her.” (Gerzina 68, 69)

Their lack of enthusiasm was likely not based on gender, because neither critic discouraged Vanessa Bell. Unlike Bell, Carrington built her distinctive style out of discernably British elements by the time Bloomsbury had become “predominantly francophile [sic]. They looked to that country for a lead in art, literature and way of life…. With this emphasis on French art and rejection of English, Carrington lost a valuable avenue of recognition among her peers.” (Gerzina 68)

It is unfair entirely to blame the boys, however, because Carrington’s contradictory inner menagerie of debilitating demons contributed to her lack of confidence. Not without cause she had described herself as “disjointed, unreliable & secretive.”

Carrington hated being a woman and hated her woman’s body. Menstruation was ‘The Fiend’ that “fills me with such disgust & agitation every time, I cannot get reconciled to it.” (Gerzina 93, 228-29)

In one letter she describes herself as an old haggis; in another, to Julia Strachey, she wishes she was “a young man and not a hybrid monster.” She longs for sex but complains to Brenan that “afterwards a sort of rage fills me because of that very pleasure.” In exasperation he advised her to “give up men and become a complete sapphist.” (Gerzina 229)

As a child Carrington loathed her domineering, conventional mother, carried the consequent guilt for the rest of her life and compensated for it by developing the obsession with secrecy. “My secretiveness,” she confided to Brenan while begging him not to disclose their sexual difficulty to his friends, “has always been my own misery.” ( Carrington 322)

As Gerzina explains:

“Her life was a series of unresolved, opposing tensions, and its consistency lay in her ambivalence to many of the problems she faced: she loved truth but constantly lied; she rejected her lovers but continually lured them back; she was happiest when she painted, but her painting frequently depressed her.” (Gerzina xvi)

The contradictions continue in cultural terms. Her dress and appearance, the conflicted sexuality and tangled domestic arrangements can appear defiantly modern but Carrington also harbored a deep “respect for many aspects of traditional English country life.” (Gerzina xvii) According to Hill, “Carrington was greatly moved by the English tradition of not-too-grand country-house living.” She “knew all the best antique shops” and “her finds filled her homes and the homes she decorated” for Bloomsbury friends. (Hill 48, 54)

All of this fascinated her contemporaries. Gertler painted her of course; Aldous Huxley, D. H. Lawrence (twice), Wyndham Lewis and Katherine Mansfield based fictional characters, not always flattering ones, on her as well.

Fascinating

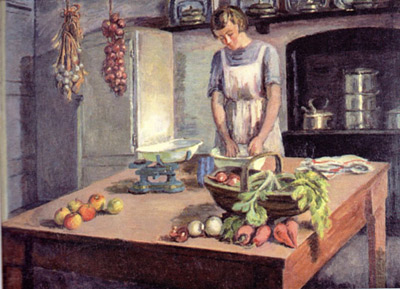

9. Carrington in the kitchen.

She was one of the better cooks of the Bloomsbury circle, not excluding the servants of the better off, but as we have seen the bar was not high, at least not at first. On meeting Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant and other members of the Bloomsbury circle while staying with them and Strachey at the Woolfs’ house in 1915, Carrington was astonished at their ignorance of domestic skills. For their part Carrington’s new colleagues “found her sturdy and eager” in contrast to their own physical indolence.

“It was,” Carrington wrote, “much happier than I expected…. We lived in the kitchen for meals, as there weren’t any servants. So I helped Vanessa cook.” (Gerzina 69)

Carrington’s comfort in the kitchen should not surprise anyone given her devotion to all things Lytton, including not least the protection of his precarious health. She also found it a place apart that satisfied her pronounced secret side, a refuge from the garrulous and often overwhelming world around her.

“In company she was,” Brenan noticed, “usually rather silent, for she was diffident about her conversational powers and preferred to keep in the background. He knew Carrington “was at her best in tête à têtes and if she liked anyone she would make great efforts to draw him out and establish closer relations with him.” (Brenan)

She liked Garnett, who like Brenan understood her shyly private side. At Ham Spray he found that

“beside the rooms created for Lytton and visitors there was a string of others which were her special province. The kitchen, of course, and the still-room where she made country wines…. Then the jams, bottled fruit and vegetables, chutneys, pickles, preserves…. The making of these was part of Carrington’s secret life. I was in her confidence in all such occupations, for I shared her tastes, and it was I who had introduced her to Cobbett’s Cottage Economy . (Ondaatje Rolls 111, quoting Garnett, Great Friends )

As the references to chutneys and Cobbett’s famously Anglophile Cottage Economy indicate, their tastes diverged from much of Bloomsbury’s. Both Garnett and Carrington cooked recognizably British food much of the time, unlike the Francophile kitchens situated elsewhere in the circle.

Carrington was resolutely English in this as in her philosophy of art and devotion to the rhythms of rural life. In these respects but not more generally Hill as well as Brenan, who hoped to claim her memory as his own and in old age demonstrated no little disdain for the rest of the circle, are right in concluding that “Carrington’s role in Bloomsbury was a satellite one.” (Hill 31; Brenan)

For if she was a satellite her orbit passed extremely close to the sphere itself, painting portraits not only of Brenan, Lytton and Julia Strachey, but of Garnett, Forster and other Bloomsbury figures. Carrington also was very nearly tireless in her devotion to them as well as to Lytton Strachey, and not only in her work within and upon the walls of their houses. Henry Lamb, who became a confidant, considered her selfless and worried about her welfare. “May I say,” he warned her, “it is obvious to everyone that you do far too much & neglect yourself?” (Hill 104, quoting Lamb)

Julia Strachey

Carrington’s letters make little reference to food, but when they do she describes dishes like her “most lovely steak and kidney pie… full of eggs, rare spices, kidneys and steak.” ( Carrington 214) In anticipation of dinner guests, “pies were baked, partridges were roasted” and “a sack posset [was] to be brewed.” ( Carrington 104-05, 365-66)

Not everything is British. She can make a velouté or those Italian dishes served for Helen Anrep, but does confide that so simple a French dish as an omelet is beyond her skill. ( Carrington 259, 365-66)

Carrington did most of the cooking herself at Ham Spray and on most occasions simpler foods prevailed. Cold chicken for lunch, a solitary supper of tinned herrings, and in a letter to Strachey a fond reference to “our fried bread and sugar sweet” appear in her correspondence. ( Carrington 461) Carrington also refers to Mrs. Beeton “sitting,” “like an immense goddess on the kitchen table presiding” at Julia Strachey’s house beyond the Bloomsbury Pale. ( Carrington 382)

Ondaatje Rolls gets all of this wrong, perhaps willfully in an attempt to bolster her breathless rendition of all things Bloomsbury. Dinners at Ham Spray were always “indescribably grand” for Strachey: Carrington “fed him like a god because to her that is what he was,” when in fact his stomach was so distressed and his health so delicate that his diet frequently was diminished. (Ondaatje Rolls 110) Their friends thought he subsisted on rice pudding alone.

“In many of her letters,” claims Ondaatje Rolls, “Dora Carrington used tempting descriptions of food and drink to lure her friends and lovers to her.” (Ondaatje Rolls 158) Again, however, references to food are infrequent in the correspondence, so Ondaatje Rolls recycles the same material to pad the small sample that does--without highlighting the practice for her reader. The “indescribably grand” dinner for instance refers to the Italian evening with Helen Anrep; Strachey was not there.

More often than not the references to food are, and typical of Carrington more generally, self-deprecating. Usually the letters refer to something that has been eaten rather than to something that will be served, while other references are to food cooked by others. In any event food was hardly the only thing that drew visitors to Ham Spray.

10. Other habitués of Ham Spray.

They became a constant, not least to satisfy the particular proclivities of the resident lovers. Ondaatje Rolls earnestly explains:

“Triangular relationships have stresses, strains and growing pains just like any other relationship, and theirs was further complicated by the fact that other people were brought in to satisfy certain inherent sexual incompatibilities: Lytton, for example, was homosexual; Carrington was bisexual and Ralph was heterosexual…. What began as a love triangle eventually became a complicated web of infidelity, passion and sex.” (Ondaatje Rolls 160)

That amounts to understatement. Later on, Ondaatje Rolls describes some of the energetic activities at Ham Spray in detail. After his marriage to Carrington, Partridge entered an affair with Frances Marshall, a translator and acclaimed diarist of considerable charm whom he eventually would marry. This, Ondaatje Rolls solemnly recites, “caused considerable friction between” the spouses, “[b]ut romance was soon rampant in Carrington’s corner as well,” in the form of an affair with the beautiful daughter of the American ambassador to the Court of St. James. That, however, ended abruptly when the ambassador’s daughter absconded “with the bisexual sculptor Stephen (‘Tommy’) Tomlin, to whom Lytton Strachey was also attracted.”

Carrington was understandably upset, but not for long. She “developed a crush on Lytton’s niece Julia Strachey, who was also Frances’ best friend from school. When that ended, Tommy re-entered Carrington’s life and they became lovers, but their relationship ended a year later.” At that point Thompson married the niece, while her uncle took up with Roger Senhouse, whom Ondaatje-Rolls murkily describes as a “literary figure.” This last affair featured “secret beatings and mock crucifictions,” which sound like fun but cannot have endeared Strachey, who also had slept with Keynes, to Partridge. (Ondaatje Rolls 168)

“Still,” deadpans Ondaatje-Rolls, “the three managed to incorporate changing interests and new lovers remarkably well.” (Ondaatje Rolls 160)

It is equally remarkable that Ondaatje Rolls has described these “changing interests” without a trace of humor or irony, but then the admiration she bestows on her subjects verges on panegyric. She does, for better or worse, have the wit to call the recipe that follows this recitation of tangled intrigue “Ham Spray Triangles.” Ondaatje Rolls found them in Partridge’s recipe book. Her triangles are simple and good and of recognizably French extraction:

“Fold thin slices of honey-cured ham round soft roes & slice in half. Heat them in a fireproof dish in a creamy béchamel sauce, to which has been added finely sliced shallots (cooked in butter & white wine) & seasoned with paprika, salt and pepper. Brown lightly under grill. Serve rolls on toasted white bread, sliced twice, diagonally.” (Ondaatje Rolls 161)

11. Something similar in Sussex.

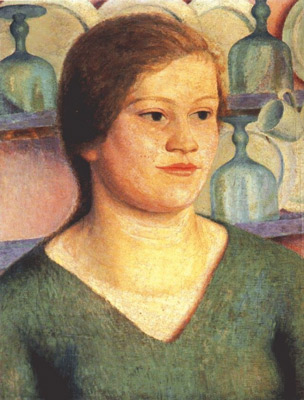

Things were not much different in contexts either erotic or culinary over at Charleston, the celebrated Sussex safety valve of Clive and Vanessa Bell, or rather of them and their extended circle of bedfellows. The Bell marriage began well. According to Ondaatje Rolls, “sexuality seemed to radiate from Vanessa’s every pore. Her bawdy sense of humor reflected her honest, happy sensual self and soon a son, Julian, arrived.” (Ondaatje Rolls 84)

Vanessa Bell

This state of affairs did not survive the birth of their child. His father resented the attention the new mother paid their son. Bell began neglecting his wife in favor of her sister and then, as Ondaatje Rolls explains in typically clumsy style, “resumed relations with a Mrs. Raven-Hill, with whom he had had a previous relationship.” (Ondaatje Rolls 85) Apparently Bell soon tired, or retired, of the mysterious Mrs. Raven-Hill and moved on, to Strachey’s cousin Mary Hutchinson. She in turn attempted without success to seduce Vanessa’s sister Virginia. Hutchinson’s amorous enterprises prompt another round of labored prose from Ondaatje Rolls:

“ ….Mary could assemble more than a few admirable dishes. She was a liberal-minded woman who shared Bloomsbury’s contempt for conventional morality. Despite her marriage to the barrister and King’s Counsel St John Hutchinson, a well-known patron of the arts, she felt no compunction about entering into simultaneous affairs with Clive, the writer Aldous Huxley and his wife, Maria…. But Virginia, while seduced by Mary’s tender cutlets and aphrodisiac sauce, would not be seduced by Mary herself.” (Ondaatje Rolls 86)

Not that Virginia herself trod the narrow path; during the course of her celibate marriage to Leonard Woolf she had sex with a number of partners including Roger Fry (whom she stole from sister Vanessa) and Vita Sackville-West. Vanessa took Clive Bell’s affairs lying down, with Fry, Duncan Grant and others. Grant, otherwise gay, was the actual father of the third ‘Bell’ child, Angelica, whom Garnett “claimed… for his own” and took as his second wife notwithstanding their difference in age of twenty-six years.

A latterly embittered Angelica would bear him four children before ending the marriage after a quarter century. During its course the marriage appeared happy and Angelica herself seemed the embodiment on a less exalted plinth of her mother’s domestic goddess mystique but in her memoir she described it as miserable.

12. Monsters in our midst?

According to Janet Malcolm, who wrote a celebrated and uncharacteristically celebratory essay about Vanessa Bell during 1995 for The New Yorker , Garnett had an unsavory side. He was, she judges fairly enough in her review of Angelica Bell’s memoir, “a chronic womanizer,” although that hardly sets him apart from the other inhabitants of Bloomsbury, unless they were chronic ‘manizers’ instead, or in fact like him, as well.

According to Malcolm, Garnett’s “preposterously pompous three-volume autobiography… diminishes him in the eyes of posterity.” While conceding that “evidently he had qualities that made people love him in spite of his faults,” which, however, Malcolm declines to enumerate, she adds that “they have not survived. He cuts a very poor figure now…. ” (“Maisie”)

Apropos of nothing in particular, Malcolm happily notes how Lytton Strachey’s biographer describes a young Garnett who

“often wore a dirty collar, usually upset his afternoon tea, and never knew what time it was. When he spoke he blinked his eyes, and generally carried on in such an irresponsible fashion as to convince his uncle, Trevor Grant, that he was a hopeless and possibly certifiable imbecile.” (“Maisie”)

Apparently Virginia Woolf did not number among the people who loved Garnett. Even though she and her husband Leonard socialized with Garnett and Angelica, and even had them round to dinner, her diaries are most unkind, labeling him variously “lugubrious,” “lumpish,” a “surly slow old dog with his amorous ways and primitive mind” and, with considerably more economy, “Bottom.” (“Maisie”)

“Bottom,” however, does not look so bad, at least not as painted by Vanessa Bell and described by Carrington, who also had him sit for a portrait.

If Malcolm and Woolf are right, then Ondaatje Rolls has ignored his horrific personality to maintain her sunny depiction of Bloomsbury. Malcolm, however, is hardly reliable. It is hard to disagree with Tom Junod on the subject of Malcolm. He pulls no punch; “for all the undeniable power of her rhetoric and the ‘nice sting’ of her one-liners (she is the Henny Youngman of self-hating journalists), she’s utterly full of shit…. very few journalists are more animated by malice that Janet Malcolm.” (Junod)

On Bloomsbury more generally she sounds malicious indeed. Charleston was “a house where sagging armchairs covered with drooping slipcovers are tolerated, and where even a certain faint dirtiness was cultivated.” Its dirty owners “occupy a minor niche” in the art of the twentieth century. ( False Starts 76, 77)

To conclude her vicious appraisal of Angelica Garnett’s otherwise favorably received memoir:

“How much of the gaping hole of self at the book’s center is due to the writer’s insufficient grasp of the autobiographical form, and how much to her incomplete self-knowledge, can only be surmised.” (“Maisie”)

Elsewhere Malcolm considers her as ‘little more than a moaner’ whose ‘unironic tone’ is ‘drab.’ (Cooke; False Starts 91)

Among the members of this purportedly overpraised crowd, “Garnett emerges as one of the least prepossessing.” (“Maisie”)

Before, during and after his marriages, Garnett did sleep with any number of men and women, including Frances Partridge, Francis Birrell and his second wife’s biological father. Like Carrington, although unlike her he reveled in sex, and notwithstanding his dismissal by Malcolm, Garnett would be a fascinating figure even without his pansexual promiscuity. For a time he lived aboard Moby Dick , a houseboat berthed in London. It was a popular anchorage for the other geometrics, an indication that despite Malcolm’s skepticism he did elicit genuine affection from his colleagues.

One of Garnett’s abiding interests was food. He served his guests Dover sole and other delights onboard the boat and kept an apiary, which prompts from Ondaatje Rolls a typically forced simile, this one about his attractions both to Bloomsbury and to bees:

“Just as a bear (or fox) is drawn to a nest of honey bees, so Bunny was drawn to Bloomsbury--and to beekeeping…. Carrington designed the woodcut for his honey label…. ” (Ondaatje Rolls 127)

Beyond that, Garnett raised chickens and pigs, grew fruit and vegetables, foraged for mushrooms, discovered a new edible strain of them, and recorded a number of his recipes accompanied by drawings.

Garnett himself does not say so but one of them, for lamb’s liver with the classically English combination of sage and onion on skewers, is a version of skuets, an eighteenth century English standby. The recipe reflects a sturdy common sense:

“I have just cooked an evening meal of lamb’s liver, and eaten it. Prepared like this: Alternate lumps of liver with sage leaves plastered against and between them and onion--transfixed by two skewers. Thus

You use two skewers because if you use one the bits of liver slide round when you try to turn them over and cook the other side. The result is beyond the dreams of the greediest gastronome. The onion is half-raw. That makes it infinitely better. The flavour of the sage is wonderful. (You have to pick the sage leaves off the liver before you eat it.)” (Ondaatje Rolls 332, quoting Garnett)

It is a well-crafted passage: His fame arose from his writing, not his food. During Garnett’s eighty-eight years he wrote some three dozen works of fiction as well as nonfiction including the memoirs. All now are forgotten except, ironically enough, his compilation of Carrington’s private correspondence. In their time they got good notices, however, and one of them was sufficiently celebrated to become a film.

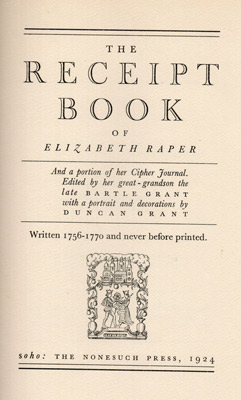

In 1924 Garnett also produced a facsimile of The Receipt Book of Elizabeth Raper in a collaboration beyond the bedroom with Duncan Grant, who illustrated the numbered run of only 850 copies. The kitchen manuscript was written from 1756 until 1770 “and never before published.” (Raper frontispiece) It represents an anomalous artifact of Bloomsbury, English in outlook and devoted to food. On the basis of The Receipt Book and his publication in 1970 of Carrington’s correspondence alone we might consider Malcolm unfair to Garnett. In terms of culinary history we might also consider her unfair to Grant.

13. An instance of rescue archeology from a source with an unexpected illustrator.

The Receipt Book represents an important artifact. Its recipes are, as its editor Bartle Grant maintains, “clearly worded and well condensed.” They also are written in charming style (“have ready laid in a china deepish dish”). (Raper 45) Except for some distinctly eighteenth century turns of phrase they could be mistaken for some of the better twentieth if not necessarily twenty-first century cookbooks now that so many of them amount to little more than pictorial tie-ins for fatuous television programs.

Its introduction, however, is recognizably a product of interwar Britain, when most British people equated good food with French food. In laying claim to an identifiable and appealing English cuisine, Grant therefore enlists the assistance of France:

“Apart from their practical value, these receipts are interesting, not only from the idea they give of the style of living in a country gentleman’s house of the period, but because they disclose a type of cuisine which approaches nearer to that of the French than to what is usually represented as English cookery. In the marinating of meat and in the treatment of vegetables this is especially noticeable.” (Raper 1)

The passage is carefully wrought to entice the reluctant reader. The recipes are practical; it is possible actually to cook from them. They are interesting, so interesting that readers unversed in English food, and Grant would have assumed many of his readers were unversed in it, might mistake them for French recipes, which means good ones. They are good enough to transcend homely cookery and ascend even to the height of cuisine.

The reference to meat and vegetables echoes in reverse Virginia Woolf’s judgment made two years earlier about sodden vegetables and leathery meat. The equation of overcooking and English food was then, as it remains, a widespread if tired trope, but in this case juxtaposition is no general coincidence. Grant’s son Duncan was the lifelong companion and intermittent lover of Woolf’s sister Vanessa Bell, and Bloomsbury was so incestuous that Bartle Grant must have been familiar with so celebrated a book as To the Lighthouse.

Examination of the recipes themselves lends a certain credence to his claim that they might be mistaken for French. By the beginning of the twentieth century, for example, burnt cream had become universally labeled crème brûlée notwithstanding its English origin. But here it is, back with its old name in a good rendition infused with cinnamon and lemon zest.

Others, however, never could be mistaken for anything but British preparations, from ‘anchovie tosts,’ ‘pull chickens,’ and ‘Indian pickle’ to ‘bread and butter pudden.’ An ineffably English ‘sauce for any meat broiled on spits’ would pair well with Garnett’s own skuets of lamb’s liver: “Mix oil, vinegar, a little pepper and salt, then add to it a little parsley, a little pickled cucumber and some shallot, all chopt very fine.” (Raper 44)

True to the tenets of Bloomsbury, money was not the motivation of Duncan Grant; nobody is going to prosper from a print run of under a thousand copies. Instead, his involvement with The Receipt Book was a labor of filial love. As he wrote on its table of contents page, “preparation of this book for the press was the last undertaking of my father, Bartle Grant, before his death.” (Raper, “The Contents”) That more than any real interest in English food accounts for the willingness of the son to participate in the project, for as we have seen foreign food found its way to the Charleston table most of the time. Nor was Duncan Grant, a fervent modernist in artistic, social, sexual and all other things, much interested in preserving the past.

Garnett, however, and also as we have seen, was, like Carrington, something of a Bloomsbury outlier in culinary terms. Both of them maintained an abiding interest in traditional English foodways. By publishing something “never before printed,” Garnett was helping ensure their survival in parlous times, for nothing about The Receipt Book supports Boxer’s claim that this cuisine made deep inroads into the consciousness of the British elite between the wars. Its tiny print run, the comparison by Bartle Grant of English to French food and the need he perceived to explain for the British just what their cookery once had been each indicates that The Receipt Book itself was an outlier in its time.

14. A pair of dualities in which the tails wag the dogs.

Bloomsbury could not have existed anywhere but England. That of course entails a perverse paradox, for Bloomsbury looked to European models for inspiration most of the time. The criticism of Fry, the painting of Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell, looked explicitly to France for inspiration at the expense of the English school and yet that inspiration produced work that could not be mistaken for anything else.

On our own mundane level the devotion of Bells and Woolfs and most of their circle to continental cuisines is, or was, entirely English too. The more dedicated Bloomsbury cooks, in the persons of Carrington and Garnett, however, did rifle the British canon for their food. They stood against the culinary stream and inadvertently kept a fading tradition from failing altogether. For that alone we owe them thanks.

Recipes from The Receipt Book of Elizabeth Raper and elsewhere appear in the practical.

Sources:

Gabriele Annan, “An Affair to Remember,” The New York Review of Books (11 January 1996)

Ann Olivier Bell (ed.), The Diary of Virginia Woolf (London 1977 et seq. )

Arabella Boxer, Arabella Boxer’s Book of English Food: A rediscovery of British food from before the war (London 1991)

Gerald Brenan, “A Hidden Life,” The New York Review of Books (1 July 1971)

Rachel Cooke, “Forty-One False Starts by Janet Malcolm--review,” The Guardian (28 July 2013)

Christopher Driver, The British at Table 1940-1980 (1983)

Irvin Ehrenpreis, “Bloomsbury Variations,” The New York Review of Books (17 April 1975)

David Garnett (ed.), Carrington: Letters and Extracts from her Diaries (New York 1971)

Jane Hill, The Art of Dora Carrington (London 1994)

Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina, Carrington (New York 1995)

Bartle Grant (ed.), The Receipt Book of Elizabeth Raper (London 1924)

Alexandra Harris, Romantic Moderns: English Writers, Artists and the Imagination from Virginia Woolf to John Piper (New York 2010)

Ambrose Heath, Good Food (London 1932)

Francis Higginson, “Eating Your Way Out: The Culinary as Resistance in Ferdinand Oyono’s Le Vieux Nègre et la médaille ,” in Lawrence Schehr & Allen Weiss, French Food: On the Table, On the Page, and in French Culture. (London 2001)

Tom Junod, “Rupert Murdoch, Meet Janet Malcolm--Pro Scandalist,” www.esquire.com (11 July 2011) (accessed 8 April 2015)

Janet Malcolm, “What Maisie Didn’t Know,” The New York Review of Books (24 October 1985)

Forty-One False Starts: Essays on Artists and Writers (New York 2013)

Regina Marlet, Bloomsbury Pie: The Making of the Bloomsbury Boom (New York 1997)

Jans Ondaatje Rolls, The Bloomsbury Cookbook: Recipes for Life, Love and Art (New York 2014)

Frances Partridge, Love in Bloomsbury: Memories (London 1981)

Julia Strachey, “Carrington: A study of a Modern Witch,” Julia: A Portrait of Julia Strachey by Herself and Frances Partridge (London 1983)

Florence White, Good Things in England (London 1931)

Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse (London 1927)