Roast beef, ovens & spits; or, all that’s old is new again.

1. What is to be done?

For something so elemental and iconic, roast beef provokes a certain controversy among cooks. A surprising lack of consensus exists about the best way to prepare it and the same holds true for Yorkshire pudding, its culinary soulmate.

Back to the beef; roasting methods range along a spectrum from fast to slow and high heat to low, or in some cases nearly none at all past the initial blast. To further complicate the issue, purists maintain that this is not roasting at all; the techniques described involve baking because a true roast turns on a spit before an open flame. They have a point, but most of us have neither spit nor flame, so the Editor cannot go so far toward historicist purity despite her tendency to visit the Old School.

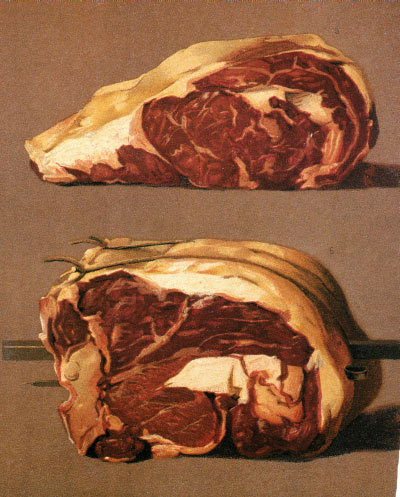

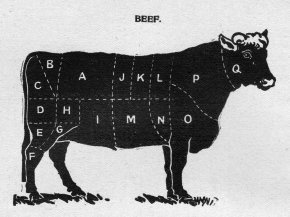

Some cooks like spice mixtures; others insist that anything other than salt and pepper masks the flavor of the meat. Some start a big roast whole and then cut slabs to sear at the finish; others find the idea of carving the beef anywhere other than at table appalling. Nor do people agree about the best cuts; top round, sirloin, tenderloin (fillet or filet) and the ribs cut for rib eyes all boast their own champions.

None of this is new. Printed sources have recorded the differing treatments for centuries. In no less a publication than The New York Times, for example, Amanda Hesser recently brought her readers the news that she had rediscovered a lost technique for roasting beef from 1966:

“Cooking beef to the right doneness, especially a wildly expensive cut like rib roast, while also tending to guests, ranks with kitchen anxieties like unmolding a tarte Tatin or killing a lobster. But Ann Seranne, a food consultant and the author of more than a dozen cookbooks, solved this problem back in the 1960s.” (“Recipe Redux”)

A lobster does not faze the Editor, but she agrees unequivocally with Hesser about the difficulty of roasting beef, although roasting a turkey for the Thanksgiving horde should be added to the list of anxieties.

But to return to technique, part of the solution that Hesser describes is a high oven temperature of 500°; the cook roasts his beef for a short period that varies by its weight, he turns the oven off and leaves the meat within for two hours. No fuss, no stress.

2. A trick of the (British) trade.

Another trick that she ‘rediscovered’ is the sprinkling of flour in addition to salt on the raw beef. For some undisclosed reason, Hesser wanted to “give this recipe to” someone who “would be nonplussed by its simplicity” and chose Harold Dieterle, a Manhattan chef “whose food is anything but plain.”

She was not disappointed. “Dieterle, who had never heard of rubbing flour into a raw piece of meat, called the recipe ‘crazy.’” He tried it, however, and liked it. What he liked most was flouring the beef: “The salt will pull out the moisture and give it a nice crunch, but the flour took it to another level.”

Hesser and Dieterle are right about the practice of enhancing the texture of beef by using flour; other cooks have joined them and Seranne to do the same thing. One of them advises her readers to take the beef and “dry it very well with a clean Cloth, then flour it all over, and hang it where the Air will come to it” for a few days before roasting. Flour remains recommended even if there is no time to hang the meat; “baste it well, and dredge it with a little Flour to make a fine Froth” at the outset of the roasting process. (Glasse 3)

The writer is Hannah Glasse, the location London and the year 1747. She is not alone. To cite a single example, a Boston edition of Susannah Carter’s Frugal Housewife, or Complete Woman Cook from 1772 instructs the reader the same way:

“As soon as your meat is warm, dust on some flour, and baste it with butter; then sprinkle some salt, and, at times, baste with what drips from it. About a quarter of an hour before you take it up… dust on a little flour, and baste with a piece of butter, that it may go to table with a good froth.” (Carter 1-2)

Lest we make an unwarranted assumption, the reference to ‘froth’ does not distinguish the effect on the crust of the beef obtained by Glasse and Carter from the ‘higher level’ of crunch that Dieterle describes. As Elisabeth Ayrton explains:

“‘Frothing’ meant sprinkling the almost cooked joint with flour and then pouring over fat or batter with or without some wine, cider, orange or lemon juice, ale or beer, so that the flour on the hot greasy skin frothed and a crisp, finely granulated surface formed as the joint finished cooking.” (Ayrton 29)

3. To roast, to bake and to crisp.

Mrs. Ayrton also delineates the distinction between roasting and baking. It is not without historical significance. For her, the advent of the oven in the nineteenth century may serve as both a cause and paradigm of the declension in British foodways.

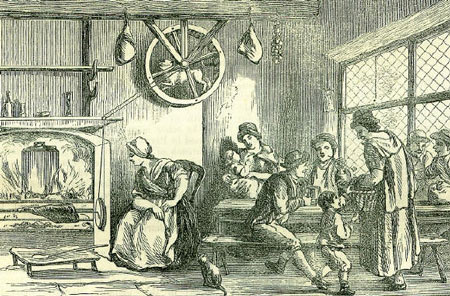

In 1577, a contemporary writer declared that “the English Cookes, in comparison with other Nations, are most commended for roasted meats.” (Holinshed cited at Ayrton 30) These meats were roasted on a turnspit, often tended by a child or, more colorfully, a dog in a treadmill. As Mrs. Ayrton explains, “[t]he ‘taste of the fire’ was what the Englishman liked, and when the spit and the jack were in general use this is what he commonly got…. The outside of the joint or bird was of great importance…. ” (Ayrton 29; emphasis in original)

With the advent of ovens that were unfamiliar to unskilled Victorian cooks, however, these big joints “were worse cooked than ever before in a country noted for the pleasure it took in the excellence and abundance of its meat.” (Ayrton 30) Primitive ovens lacked thermostats and decent damping, so that the variable quality of fuel and wind conditions prevented cook from controlling their temperatures. The results could be dire. Meat lost not only that ‘taste of the fire,’ but also might emerge either sodden and raw or cremated to a dry and fibery grey.

Attempts to rectify these problems exacerbated them; stewing the meat in rancid fat gave the greasy exterior a bad flavor and potatoes engulfed in the fat prevented the meat from browning and themselves emerged a sticky, soggy mess. “Some cooks even committed the heinous crime of putting a little water in the roasting tin so that the meat was partly steamed, in fact not roast at all but braised without the benefit of vegetables, herbs or seasoning.” (Ayrton 30)

Baking therefore is not roasting; “meat cooked with dripping or butter in the oven is really being baked and not roasted at all.” This is, however, a cautionary tale rather than a surrender to inferiority because, as Mrs. Ayrton also explains, baked meat “can be perfectly cooked and should be indistinguishable from one cooked on the spit.” This, quite literally, is where the flour comes in, for Mrs. Ayrton follows the quoted passage with her stern instruction to dust all roasts with that ‘highly seasoned flour’ to achieve something like the ‘taste of the fire’ with a crusty finish. (Ayrton 30)

4. Closer to 1776 than to 1966.

Keith Stavely and Kathleen Fitzgerald describe the passage from The Frugal Housewife as part of “a typical English recipe from roast beef’s golden age…. Carter’s tips for a perfect roast… were recommended by nineteenth-century writers as well and of course are still useful.” (Northern Hospitality 235-36)

One of them is Eliza Acton, whose landmark Modern Cookery for Private Families first appeared in 1855. She advises the cook to take either a sirloin or rib roast of beef and “dust some powdered ginger or pepper over it” and “have it dredged with flour when it is first placed at the fire, and sprinkled with fine salt when it is nearly done” as an equally appealing alternative to frothing the roast at the finish line. (Acton 170, 171)

In fact, British cooks have coated beef with flour on a continuous basis for at least five centuries. Robert May recommended “divers ways of breading or dredging meat to prevent the gravy from too much evaporating” and provides seven alternatives, including “Flour mixed with grated bread” in The Accomplisht Cook from 1660. (May cited at Ayrton 29)

Mrs. Ayrton herself, no slouch on the page or in the kitchen, is unequivocal about flouring any roast:

“The whole outside of the meat should be rubbed lightly with highly seasoned flour; a little garlic salt may be added to this, and for mutton or pork a little powdered thyme; or sprigs of fresh rosemary may be stuck into the fat of either of the latter.” (Ayrton 30)

This was during 1974. A decade later Jane Grigson would do all of our exemplars a turn better by rubbing down her beef with a mixture of mustard flour, sugar and Dijon mustard: The effect on the texture of the outside cut is the same but the spicing is sublime. (British Cookery 118)

Three years earlier than Mrs. Grigson, Jane Garmey published Great British Cooking: A Well Kept Secret. Its title is apt enough and the book is pleasant, if by its own admission not comprehensive. It could not be described as mining the historical magma for hidden ore but nonetheless includes instruction to flour the skin of a goose before roasting to create a crisp crust. The recipe for roasting beef fails to flour the meat but does bake it at a high temperature of 450 for a short time, just over an hour for a four pounder.

In 2009, Dick Sawyer, the chef at Rules in Covent Garden, followed suit. His advice? He uses grass fed beef aged for thirty days and “seasons the outside with Colman’s mustard, sea salt and ground white pepper to give it a crispy outer crust.” (Stogdon) The Colman’s of course is pure dry ground mustard, called variously flour or powder.

Neither is the use of extreme temperature followed by rest anything unique or new. The 1984 recipe from Mrs. Grigson does much the same thing and so do a number of others. Mrs. Ayrton, however, starts her oven at 400° before reducing the temperature by fifty degrees after ten minutes. Other cooks slow roast their beef for hours; all of them create a good, rare roast.

5. Americans adopt a lot of BTUs too.

These references are British; what about the United States? It would appear that a 500° degree oven is not so unknown at the western end of the Atlantic either. The self-congratulatory but oddly practical socialite Julia Reed, for one, published a recipe nearly identical to Seranne’s in 2008 but for the flour; she uses butter to similar effect. In fact her version is even simpler. The description appears in Ham Biscuits, Hostess Gowns and Other Southern Specialties:

“There is nothing easier or more delicious--simply preheat the oven to 500 degrees, rub a boneless rib roast with lots of butter and salt and pepper and cook exactly five minutes per pound. Then turn the oven off, but don’t open the door, and leave the meat inside for another hour and a half. It will be crusty on the outside and a perfect rare to medium-rare on the inside, and the entire amount of prep work is less than five minutes.” (Reed 72)

So Seranne herself did not ‘solve’ any problem that had not been eliminated earlier, and the technique that she described was never lost. Journalism may not aspire to the intellectual ambition of historians but at some point it becomes worthwhile to ask how little research we ought to tolerate.

Carter was not the only English author published in the United States, and the practice of printing American editions of British cookbooks continued unabated into the early twentieth century. Editions of Glasse, Acton and countless others became bestsellers in North America. The book by Mrs. Glasse, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, was the best selling book, in any language on any subject, of the eighteenth century. There, instructions for roasting beef with a dusting of flour appear on the first page of the text, so its location is hardly hidden. Carter followed suit; her recipe for roast beef frothed with flour covers the first two pages of The Frugal Housewife.

In our own era, Reed’s recent book is not obscure, and received favorable notices, including an enthusiastic review in The New York Times itself.

6. A quick coda.

None of this demonstrates that it is particularly fair to round on Hesser. She is an engaging writer, posts good recipes like ‘rib roast redux’ and seems like a nice enough person. The lesson from her article merely reflects the broader fact that Americans no longer consider Britain when they think of food.

Recipes for roast beef and Yorkshire pudding appear in the practical.

Sources.

Elisabeth Ayrton, The Cookery of England (London 1974)

Susannah Carter, The Frugal Housewife, or Complete Woman

Cook (Boston 1772)

Hannah Glasse, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy

(London 1747; Prospect facsimile 1995)

Jane Grigson, The Observer Guide to British Cookery

(London 1984)

Amanda Hesser, “Recipe Redux: Rib Roast of Beef,

1966,” The New York Times Magazine

(25 January 2011)

Raphael Holinshed, Chronicles of England, Scotlande,

and Irelande (London 1577)

Robert May, The Accomplisht Cook (London 1660; Prospect

facsimile 2000)

Julia Reed, Ham Biscuits, Hostess Gowns and Other Southern

Specialties (New York 2008)

Keith Stavely & Kathleen Fitzgerald, Northern Hospitality:

Cooking by the Book in New England (Amherst 2011)

Catalina Stogdon, “Traditional British Food for St Georges’s

Day,” The Telegraph (20 April 2009)