The wine of choice in the Age of Revolution, or, Madeira the muse & its uses, with two book reviews.

1. Good times and bad for the best of them all.

Fortified wines have fallen from fashion, at least among most Americans. The wines are an afterthought if anyone thinks about them at all, but that once was not so. It is hard for most people to imagine their ubiquitous place on tables throughout the North American seaboard and across the Gulf of Mexico during the long eighteenth century. Madeira ranked first among those fortified equals then, but has receded to obscurity even in comparison with Sherry or Port.

It was the taste of revolution and the toast of the club. As Emanuel Berk, owner of the Rare Wine Company, contends in his introduction to Noel Cossart’s poignant Madeira: The Island Vineyard: “Of all the wines created over the past five hundred years, there is none that lays greater claim to being a wine of its time and place as Madeira, a highly improbable beverage forged by fire and heat.” (Island xxviii)

And yet, of all the world’s wines, there is

“none that has faced, and continues to face, such great challenges to its ongoing existence. But while those of us who love this heroic wine can do little more than hope for a profound change in its prospects, we can take comfort not only in the glorious old wines that have survived, but in Madeira’s improbable, yet incredibly rich, history.” (Island xxxv)

Warfare, phylloxera and the vagary of taste nearly killed the wine; again citing Berk, “Madeira flirted with extinction in the early twentieth century…. ” By 1987, when Cossart died, “[v]irtually all the traditional markets for Madeira had all but disappeared, and with them scores of companies who had made Madeira one of the world’s most magical wines.” (Island ix)

Cossart’s is one; he is a tragic figure who struggled for a lifetime to hang onto the business. His book, however, is no study in self-pity but rather the charming celebration of an island and its wines. Elizabeth David of all people liked it and liked Cossart himself, unlike so much that she read and so many she met. David corresponded with him and gave Island Vineyard an ecstatic review:

“He is to be envied. He is also to be congratulated. His book is as rich with the lore of his subject as is his mother’s bolo de mel, the true cake of Madeira (good though it may be, the English one is an imposter)…. ”

Cossart demonstrates “a delightfully easy manner and perfectly unpretentious language.” (Tatler 26)

The review is classic David, dead certain in her take and certain to take a swipe at English food. That she liked the man and his work should not surprise, for we see her in him. Cossart, like David, is a voluble amateur in print, whose persona draws us to each page despite some errors of judgment and fact.

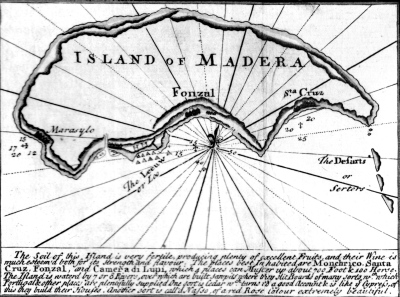

If Island Vineyard has been overtaken and in some details overturned by subsequent historiography, it tells a good tale, recounting the once inextricable tie to North America and implicating some of the great figures of history. Funchal, the island capital, derives its name from the pipes in which its wine was shipped… or maybe not. Bonaparte makes his appearance, and we learn that both Anson and Benbow, Royal Navy titans in the age of fighting sail, wrote of Madeira and its wine in their ships’ logs.

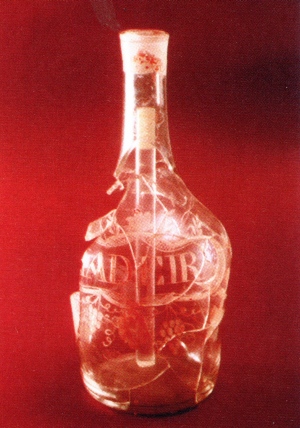

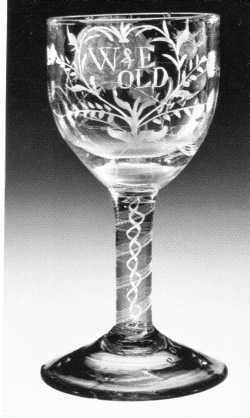

Jefferson’s Madeira decanter

Then, the vineyards of the island may have covered some 2,500 hectares; today, however, only an estimated 300 to 420 remain, and they are fractured into some 3,000 smallholdings. The last of the great British vinting families has left the island after five hundred years to join the ghosted cultures of Ascendancy Ireland and Fredrickan Prussia. The Anglo-Madeirans’ extinction is ironic, for they created the sunstroked and fortified Madeira style that is familiar to us (well, a few of us anyway) to combat the constraints of preserving foodstuffs in equatorial waters. (Island xxxvii)

The trade in Madeira was so significant then that it slaked the thirst of every empire, not just the British from India to North America and the Indies below, but also the Dutch in their Asiatic islands, and the holdings of Portugal at Goa, in the Azores and Brazil. The Danish East India Company carried the wines to all of Scandinavia; France, the German states and Russia consumed it in quantity; the French fobbed out knockoffs as well, mislabeled variously as Madere de l’Ile, Madere de l’Origine and vin de Madere. (Tatler 26)

2. The complex role of a complex commodity.

In Oceans of Wine, David Hancock has written a fine but flawed book on a single strand of the story, the networks that brought the wines to America. It is a considerable accomplishment, because the proliferating studies, both academic and popular, of a single commodity frequently fail. Hancock belongs to a shrinking fraternity, the rigorous historian who can write with the best, until he pulls back as if anxious that his academic colleagues would mistake clarity for a dearth of gravity. We get engaging set pieces and soulkilling cant.

Here is Hancock in form on stumbling into his quest: He flew to Madeira for sun but it rained. He got bored. To kill the time he took a tour of the Madeira Wine Company; he found it “illuminating and the samples invigorating” but the eighteenth century ledgers scattered as atmospheric props intrigued him more. Were there others and where? There were, in a hilltop warehouse:

“There on the top floor was a cavernous room, open to the elements, with wooden shutters dangling on rusted hinges and birds flying in and out. What surprised me most was neither the dead chickens nor the mushrooms the size of grapefruit growing from wooden boxes nor even the skeleton of what probably had been a goat, but the mountain of papers and books, probably twenty feet high and forty feet in diameter, cast there in abandon.” (Hancock xiii)

But we also get this:

“As an analytical matter, emergent phenomena need not and often do not look like constituent parts… and a market is not a goal-seeking actor in the way that an entrepreneur may be. Understanding phenomena as emergent removes the constraint of having to apply the same historical constructs to all levels of analysis…. Nevertheless, this approach imposes an obligation to explain the relationships among levels (something that is often not done).” (Hancock 424-25)

So people are not things, markets are not people and markets do not think; this obfuscation of the obvious unhappily recurs in Oceans of Wine.

At other points the obvious appears as revelation, from beginning to end. At the outset: “As the population of the island grew, so, too, did the capital city grow and its institutions evolve…. ”Perhaps an ‘explanation of relationships among levels?’ Then in conclusion (literally; the last line of text):

“Even today, business pundits are rediscovering the modes of organization these eighteenth-century entrepreneurs used--conversations, informal and indirect exchanges, networks, local autonomy, and informal empires. Now, these organizational strategies are essential; modern businesses must adapt quickly to sudden changes in the economy. But the market has been evolving rapidly for the last five hundred years.” (Hancock 21, 407)

Perhaps this is meant as a plug for the relevance of history, but never mind the contradiction inherent in juxtaposing newly ‘sudden change’ against ‘five centuries of rapid evolution;’ only someone who never has inhabited the workaday world could think that any of this requires ‘rediscovery.’

In between, however, there is a lot to like about Oceans of Wine. It proves despite the critics that interdisciplinary study belongs within the arsenal of the historian. Hancock ranges across anthropology, architecture, demography, ecology, economics, geography, oenology and sociology--as any historian should but not many do.

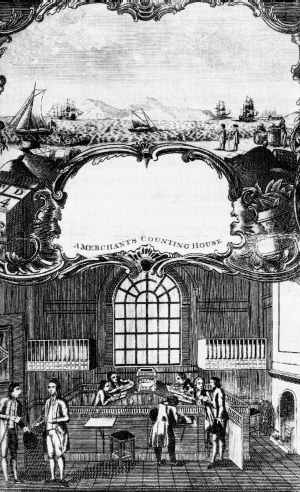

Oceans of Wine explains why and how the island became so cosmopolitan over the course of the long eighteenth century; explores the transformation of its ecology; and analyzes in depth its patterns of land ownership and the process of making Madeira. The book tracks patterns of trade that increased by dramatic leaps of both volume and complexity. It assesses aspects of material culture around the Atlantic rim, including the glassware and other paraphanalia that evolved for display in connection with the highly socialized consumption of wine. Hancock ponders the infrastructure of the harbor at Funchal, architecture of both the residences and counting houses built by Philadelphia wine merchants, and habits both of tavern owners and their customers throughout inland North America.

It is a fascinating ride. Why did colonial Americans import instead of produce their wine? “This was not because of ‘ignorance of established methods’ or for want of trying. Rather, climatic extremes, insects, bacterial infections, rot funguses, and mildew killed European vine stock in America. Until the development of hybridized varieties, Americans had no viable grape alternative to imported wine.” (Hancock 110) Enter Madeira, one of the few wines that did not spoil in transit across the sea.

Other questions remain open, and Hancock has the integrity to admit it; unlike a Clarissa Dickson Wright or Deborah Valenze, he refuses to speculate. Thus, we do not know much about how those merchants furnished either their hoses or offices; “odd, given their prominence in the early American cityscape.” (Hancock 232)

Uncertainty does not prevent Hancock from asking good questions, and he shares them:

“Little direct evidence reveals why storekeepers added wine to the products they sold after the mid-eighteenth century…. There does not seem to have been a change in consumers’ buying habits; for example, there was no temperance movement… or a shift in the gender of the family liquor buyer--and even this presumes women felt less comfortable in taverns than men, which does not seem to be the case. On the sellers’ side, storekeepers and tavern keepers had access to the same importers…. The most likely impetus … was the increased availability of family-sized containers…. Early in the century, ceramic and glass containers were hard to come by in British America.” (Hancock 246)

Hancock’s restraint, imagination and synthetic skill not only are impressive; better, the effect is of conversation with a learned friend.

His inquiries serve “the principal concern of Oceans of Wine,” and it is close to the ground; “the connections among real people--wine producers, distributors and consumers--and the institutions they developed over a 175-year period,” not, however, that Hancock ascribes much impact to institutions above the local level. (Hancock 394)

From this we might expect an Annales approach, but Hancock disavows that line of thought other than its rejection of national government as a leading driver of change. Oceans of Wine does not, he warns, accept “the popular perspective that social and economic transformations of the early modern Atlantic world can be understood in terms of geography, climate, technology and state policy.” (Hancock 393) That would at best provide “only partial insight into the participants’ lives, labors, behaviors, and attitudes…. ” (Hancock 393-94) Why that should be the case remains unclear from Oceans of Wine.

The book unfortunately gives no shrift to historians like John Brewer either, who has sought to demonstrate the long reach and deep impact of the English state on the development of that world via tax policy and financial innovation, as, to his credit, Hancock admits. He may not believe that the politics of statute and treaty matter much, and only skirts a subject interwoven with his narrative; but the ‘oldest alliance,’ for example, between Britain and Portugal, did a great deal to facilitate the transatlantic Madeira trade.

Hancock does believe in contingency, however, and studied at Harvard under Bernard Bailyn in his mature incarnation, when the great man’s interest had burst the confines of intellectual history to create the welcome if belated school of Atlantic History. So Hancock is an Atlanticist with all that that implies, eager to find complex patterns of trade and cultural exchange all the way around the Atlantic basin. In that task, and in charting the lives of its inhabitants, he has turned in a bravura performance.

3. You can drink it too, and help preserve the past.

Given its economic, political and cultural significance, it seems all the more shocking that Madeira became marginalized. Exceptions to its general neglect only prove the rule. A few years back, Berk’s Rare Wine Company began importing its Historic Madeira Series. Vinhos Barbeito, an old firm that holds some of the largest lineal stocks from the nineteenth century on the island, blends the wines in the series.

Rare Wine describes its Madeiras as “affordable,” but these are expensive bottles ranging in price from around $45 to as much as $65 a pop. As a result they have done anything but introduce Madeira to much of “a broader market,” the stated goal of the Company. Nonetheless the Historic Series does have a coterie of loyal customers, including the Editor.

That unfamiliarity with not just the Historic Series but with Madeira more generally is too bad, because they are exceptional wines, at once accessible and complex. As Berk explains, “its palate is uniquely blessed by powerful acidity, which amplifies every flavor and dramatically frames the wine’s honeyed richness, making it seem both less alcoholic and less sweet…. ” (Island xxix)

The blended wines in the Series vie with the great vintage Madeiras of the nineteenth century in quality. They are refreshing and bracing, subtle and yet strong in all of their manifestations; two dryish Sercials, a slightly sweeter Verdelho and then up the sugar scale from Bual to Malmsey.

Despite its high prices, the Historic Series provides good value for money, not only because the wines cost less than, say, a Port of comparable quality, but also because they are indestructible. Madeira is aged in a hot hot climate and, in a sense, ‘cooked’ like Bourbon in the warehouse. You can open a bottle, pour a glass or two, recork it and keep the wine indefinitely, unlike a fine Port or even Sherry.

It is not unfair of Rare Wine to describe lesser blends of Madeira as lacking the “magic and distinction that marks [sic] the great vintage wines.” They also cost considerably less, however, usually a little under half the price of comparable grades from the Historic Series. Rare Wine is right about the superiority of its product, but that begs the point. Cheaper blends may not be as magical but perform their own impressive tricks for the price.

Blandy’s and Broadbent, the only brands ‘widely’ available in the United States (a decidedly comparative term; only the most serious of wine shops seem to carry any Madeira outside New England), both offer reliable and lovely wines. Rainwater sports about the same proportion of sugar as Verdelho, but the Verdelho from either producer is incomparably more interesting if harder to find, the less heterogeneous blend of the two. The Editor scorns convention and drinks these off-dry wines chilled.

The story is different in Britain, if only in significant degree. Fortified wines enjoy comparatively more popularity there. While it almost is impossible to find a glass of dry Sherry to sip as an apertif on American menus, even middling restaurants offering most kinds of cuisine in Britain will offer one at least and usually more. Ports appear too, for the back of the meal, but almost never Madeira; its popularity may not have outstripped per capita demand in North America during the golden age, but people still drank a lot of it. Today the wine has virtually disappeared from the British Isles.

4. Complexity in the kitchen.

Fortified wines also have done faithful duty as helpmates for the cook, in particular for adherents of traditional British foodways. The past tense is deliberate usage, for with a couple of exceptions, fortified wines have vanished from the kitchen too. That is a shame; something about their intense flavor and chewy texture enhances any sauce and many soups or stews.

It should be no surprise that the exceptions, Marsala and vermouth, both are Mediterranean in origin. More irony; Marsala originated as another copycat eager to share the success of Madeira by attempting to replicate its character, and originally traded under the name ‘Sicily Madeira.’ (Island xxxi)

The waves of nineteenth century immigration transformed American foodways to the extent that Italian became the default cuisine for restaurants across the United States. Americanized Marsala-based dishes are ubiquitous in hyphenated establishments. An Italian from Europe may not recognize the food served in obscene portions, but they would find Marsala in much of it.

The survival of kitchen vermouth may stem from a different and singular source: Julia Child. She liked vermouth and liked to cook with it, so it featured with prominence in her blockbuster book and became a reserve currency for ambitious American cooks. It is not at all a bad product, but the varying bouquet of herbs and spice that flavor the wine render it awkward for a lot of things. It is not the universal elixer that Child considered it, but in the right place does provide the intense density that all of fortified wine contributes to sauce.

For some reason Champagne has a similar effect, somehow brighter and more densely textured than a still table wine. It does not get much use in contemporary kitchens either, despite the fact that the sparkler has been a staple of both British and American tables for centuries. British ones even more so, to the extent that during any given year during the last hundred, the British have consumed more champagne per capita even than the French.

It therefore seems surprising that Champagne appears to have found more favor in the kitchens of the American south than in the British Isles. A particularly good recipe for chicken with Champagne appears in The Savannah Cookbook by Damon Lee Fowler.

Madeira, however, retains a relative ascendancy in southern kitchens. Scott Peacock and Edna Lewis bake a whole ham with buttered Madeira. Cooks in one city appear particularly enamored; Fowler, who lives there, writes that “in old Savannah kitchens, cooks put the city’s favorite wine to many uses.” (Savannah 146) He does not exaggerate the taste that Savannah retains for Madeira. When Christie’s published the first edition of Cossart’s Island Vineyard, the auction house launched the book with three galas, in Funchal, London and Savannah, at its Madeira Club.

Fowler uses Madeira to pan fry chicken livers with bacon, braise pork chops, nap pounded tenderloin and build pan gravy for all species of roast birds and meat. It enhances his desserts too, in pots of English custard, a syllabub and in a sauce for sponge cake. Fowler considers Madeira so important to the cuisine of Savannah that a glass of the wine and its bottle appear on the cover of the cookbook.

Best of all, Fowler appropriates a recipe for chicken with Madeira from Four Great Southern Cooks, the 1980 cookbook that gives deserved homage to the “vanishing breed” of African-American “live-in cooks who, through a lifetime of practice, turned Southern cooking into an art.” The Chicken Madeira recipe belongs to Daisy Redman, also of Savannah. Her preparation includes leeks, shallots, mushrooms and salt pork, and alone could demonstrate why Four Cooks has acquired a cult following in the south.

The wine on the left…Madeira

None of this should imply that there is no British recipe that uses Madeira, or at least nothing written by a British author. Jane Grigson maintained that “Madeira is a good wine to use in cooking, much better than sherry. The rich sweetness blends well with mushrooms in particular;” she published recipes for both mushrooms in Madeira and for a Madeira sauce loaded with them. (Mushroom Feast 43-44, 89-90) Elizabeth David, however, seems not to have noticed despite her review.

Madeira is nice for napping grilled slices of pungent black pudding or kidney as well and marries with meats that are not offal too.

Mrs. Grigson found a passage from 1791 in Parson Woodforde’s diary describing a dinner of “Beef-stake tarts in turrets of paste” that were sauced with Madeira. Her version from Food with the Famous tops little steaks with a slurry of buttered onion and mushrooms, and bakes them encased by puff pastry; the sauce is a study in simplicity, more of the slurry thinned by stock and finished with Madeira. It is timeless and typical of traditional English food.

The often eccentric and always engaging Patience Gray includes a recipe for haddock baked with Madeira in The Centaur’s Kitchen. (Totnes, Devon 2005) We guess that she would have considered her preparation British because as an alternative she notes that “[h]addock is also good cooked in draught Guinness.” (Gray 88)

To begin and end your flight of Madeira dishes, Michael Smith weighs in with an easy flourless mushroom soup and, on the sweet side, laces his brown bread ice cream with Madeira.

5. A muse for modern times.

Finally we would adore Madeira for one reason alone, and unrelated to flavor or food. It has inspired one of the great comedic songs of all time, from the late and lamented Flanders and Swann. In “Madeira M’Dear” an old letch celebrates the exemplary erotic impact of the elixir. In tantalizing part:

“She was young, she was pure, she was new, she was nice,

She was fair, she was sweet seventeen.

He was old, he was vile and no stranger to vice,

He was base, he was bad, he was mean.

He had slyly inveigled her up to his flat

To view his collection of stamps

And he said as he hastened to put out the cat,

The wine, his cigar and the lamps:

“Have some Madeira, m’Dear!

You really have nothing to fear….

Unaware of the wiles of the snake in the grass

And the fate of the maiden who topes,

She lowered her standards by raising her glass,

Her courage, her eyes and his hopes.

She sipped it, she drank it, she drained it, she did

And quietly he filled it again….

Then it flashed through her mind what her mother had said

With her antepenultimate breath:

“Oh my child, should you look at the wine which is red

Be prepared for a fate worse than death!”

She let go her glass with a shrill little cry

Crash! Tinkle! It fell to the floor.

When he asked “what in Heaven?” she made no reply,

Up her mind, and a dash for the door.

“Have some Madeira, m’Dear!”

Rang out down the hall, loud and clear,

A tremendous cry that was filled with despair

As she paused to take breath in the full midnight air.

“Have some Madeira, m’Dear!”

The words seemed to ring in her ear

Until the next morning, she woke up in bed

With a smile on her lips, an ache in her head

And a beard in her ear hole that tickled and said:

“Have some Madeira, m’Dear!”

Note:

- The Centaur’s Kitchen a good book with a bad title. Ships do not have kitchens; they have galleys.

- Recipes incorporating Madeira appear in the practical.

- Copies of Madeira: The Island Vineyard may be purchased direct from the Rare Wine Company by calling (800) 999-4342.

Sources:

Noel Cossart, Madeira, The Island Vineyard (2d ed.,

Sonoma 2011; new material by Emanuel Berk)

Elizabeth David, “The Madeira Era,” Tatler (June 1985)

Damon Lee Fowler, The Savannah Cookbook

(Salt Lake City 2008)

Patience Gray, The Centaur’s Kitchen (Totnes,

Devon 2005)

Jane Grigson, Food with the Famous (London 1979)

The Mushroom Feast (London 1975)

David Hancock, Oceans of Wine: Madeira and the

Emergence of American Trade and Taste

(New Haven 2009)

Edna Lewis & Scott Peacock, The Gift of Southern

Cooking (New York 2003)

Daisy Redman et al., Four Great Southern Cooks (Atlanta 1980)

Michael Smith, Fine English Cookery (London 1973)