A study in conflict & contradiction: Mark Bittman.

1. History? Who needs stinking history?

Back when britishfoodinamerica began six years ago, we identified Mark Bittman as a celebrity food writer who ignored the British tradition. “When, for example,” we wrote,

“ The New York Times columnist Mark Bittman produced his best-selling The Best Recipes in the World in 2005 after ‘a rather intense five or six years’ of research, he did not even include an entry for British food in his index of ‘Recipes by cuisine.’ That omission lies in a book running to some 768 pages that does include recipes from all around the Mediterranean rim, Africa, most of Asia including Hong Kong, continental Europe of course and even Scandinavia.” (citation omitted)

With luck our prose has improved, and we also might have added that the oversight is all the more remarkable because in historical terms British books on cooking dominated the American market until well within the twentieth century.

Perhaps Bittman has no historical perspective or knowledge. In 2015, Mimi Sheraton lobbed a bomb at what she considers his self importance. Her letter to the Times is worth lengthy quotation:

“Mark Bittman writes that when he began his column five years ago, ‘food was not generally considered as serious a subject as it is now.’ I disagree.

Food issues have been taken seriously from the days of Upton Sinclair to Marion Nestle, from Kellogg and Fletcher to Adelle Davis, Joan Gussow, Alice Waters, Science in the Public Interest, and Drs. Robert Atkins and Dean Ornish, not to mention Frances Moore Lappe’s 1971 eye-opener ‘Diet for a Small Planet,’ long before Michael Pollen’s prescription ‘Eat food. Not much. Mostly plants’ in 2007.

Food has been taken seriously in all aspects ever since people gathered in cities and dealt with corruption, adulteration, fair treatment of workers, health, poverty, and the rest.” (Sheraton)

Sheraton confined her letter to American sources. During the nineteenth century in Britain concern about providing decent food to the poor reflected a perception of crisis. To cite but two examples, Charles Francatelli, Victoria’s chef, wrote Plain Cookery for the Working Classes out of concern that the new industrial order uprooted from rural life could not fend for themselves foodwise in the emergent cities. Reform Club icon Alexis Soyer was acclaimed (but also ridiculed) as “the peoples’ chef” for his charitable work as well as guides for inexpensive cookery both in England and abroad. Soyer joined Florence Nightingale in the Crimea to address the dire straight of catering for the Army and attempted, with less success, to implement famine relief in Ireland. More generally, British legislation addressed a number of issues involving food, including adulteration and quality control.

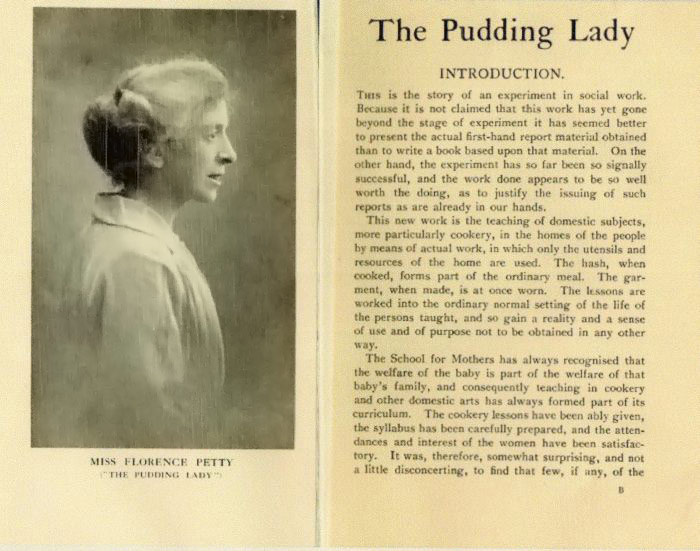

Florence Petty, The Pudding Lady

During the first half of the twentieth century Florence Petty, who became known as the Pudding Lady, was a star of BBC radio for her broadcasts about food. A bright star indeed; hers was the network’s most popular program through the 1920s. Petty’s abiding concern was nutrition for the poor. She earned her sobriquet not through marketing but because she took her cooking course into the sparse kitchens of workingclass wives and conjured not only nutritious but also palatable foods, including the puddings that the children of her charges adored. Like her forebears Francatelli and Soyer she wrote books aimed at the market of modest means, and she would outsell them both even accounting for the increase in population.

Sheraton, it would seem, had had a point, which may not matter much. Bittman has enjoyed an affiliation with Berkeley and also lectured this Fall at Columbia, an institutional exaltation of celebrity over scholarship. We should not, however, single out Columbia; Yale has had the dubious judgment to impose David Brooks on its undergraduates, while it is horrifying to speculate what kind of charlatans lesser schools employ to amuse their students.

2. Good intentions out west?

Sheraton sent her letter when Bittman had decided to leave the Times for Berkeley, an epicenter of faultline tremors not only geological, political and metaphorical but also culinary. Bittman liked his time there, where incidentally British foodways are not much in evidence around San Francisco Bay.

At first he would appear to be a difficult figure to fault, but warning signs lurk in the middle distance. Some of the company he keeps has been suspect, including the odious Gwyneth Paltrow, perpetrator of “Goop!” When Bittman left the Times , he wrote in one of his farewell columns that he was “leaving to take a central role in a year-old food company, to do what” he had “been writing about these many years: to make it easier for people to eat more plants.” It looks pretty good for a man of 65 to take on so creditable a cause and choose so risky a course.

The startup, however, is The Purple Carrot, a company engaged in the dubious enterprise of selling vegan food kits. Double trouble; first, as Jane Brody, ordinarily a hypochondriac killjoy afraid of things like salt, beef and salt beef (nitrates and ‘trites) recently noted, the vegan life is not ordinarily a healthy nor, we would add, satisfying life. (Brody) Second, the concept of meal kits more generally is both ludicrous and extortionate. If you cannot cook then obtaining ingredients that have been measured or chopped will not save you, and anyway those are the easiest operations to conduct in the kitchen. The waste from packaging is even worse than the wasteful packaging of conventional groceries, while the surcharge all this entails is indefensible. May the vogue for kits be short lived and unlamented.

3. The end of all that.

Bittman’s tenure at Purple Carrot, it turns out, itself was short lived. The details of his departure remain obscure, but as one headline said it was “A Strange Sequence of Events at Purple Carrot.” (Horgan) After only a few months he and they divorced with the standard disingenuous testimonials of mutual regard. “I wish the company nothing but the best,” Bittman said, while the company itself claimed he “remains a friend.” (Philpott)

The friendship did not last, perhaps in retrospect because Bittman decided that his erstwhile cause was not so creditable. He has mused that his affiliation with Purple Carrot “might have been a mistake” (“What I’ve Been Up To”) and does not mention the company on his website. A year after leaving the meal kit business, Bittman attacked it in print under the banner “Mark Bittman: Here’s Why Meal Kits Like Blue Apron Are a Waste of Your Money.” “I don’t think meal kits are consumer driven,” he told Money magazine.

“I think they’re venture capitalist driven. There’s not a demand for meal kits; meal kits are creating their own demand…. Meal kits are the flavor of the month…. I think the packaging really turns people off. Have you seen a meal kit? It’s massive. You get these boxes, you unpack the food, you have a few little bags of food, and now you have this enormous waste problem. And they’re not inexpensive. If you know how to cook, you can prepare meals for much less money than what meal kits are costing you.” (Nova)

The criticism of the kits is sensible enough but in context passing strange. Did it require his time at Purple Carrot to figure that out? What else could have been the components of kits?

4. Capitalism? Who needs stinking capitalism?

Bittman, it transpires, also purports to be “essentially anti-capitalist.” “In my heart,” he has confessed, “I don’t believe making money is an honorable goal, even if it’s ostensibly linked to doing good things.” (“Harder Than I Thought”) Making money, however, cannot be dishonorable if the alternative is the starvation of your family.

Bittman also has conflated two concepts. Making money and capitalism are not congruent; means other than capital accumulation may support a living, as millions of people who lived in the Soviet Union can attest. Does the reference to capital driving the meal kit industry demonstrate a deep loathing? As an aside it would be difficult to guess how someone without a substantial inheritance might survive without making money, but then consistency has not been a bugaboo for Bittman.

5. A flexitarian.

Notwithstanding his serial print protestations of passion for “social justice,” Bittman can emit a mercenary smell. He kept a stake in Purple Carrot after his departure. That and his choice of Money as the platform for criticism of its business entail a certain irony. While attacking venture capital he also was taking a consultant’s fee of $90,000 from an “activist investor,” in fact a hedge fund, bent on profiting from the distress at Whole Foods. Bittman also bought stock in the company before its sale to Amazon in hope of making a gain. (Haddon & Benoit)

The irascible Sheraton is similarly skeptical of his motive. Never a person to suffer fools or tolerate hypocrisy, she posted an exasperated tweet in response to Bittman’s long farewell: “How many times is the Times going to let Mark Bittman say goodbye in self-advertisements and plugs for Purple Carrot? Good-bye Already!”

Notwithstanding his enthusiasm for the vegan, some of the time anyway, it is a relief to report that upon his return to the east coast--he chose the Hudson Valley almost by cliché--Bittman is cooking with meat, “offal, shins, feet,” coincidentally traditional staples of the frugal Yorkshire kitchen, which with characteristic self congratulation for his devotion to sustainability he describes as “the less popular bits.” (“What I’ve Been Up To”)

A logical post-Purple Carrot move.

6. A confident person.

He may have bungled his brush with business at Purple Carrot, but Bittman does not want for self esteem despite an awkward writing style. He explains why, despite his disdain for profit, he had joined the company. Its founder, he claims, “wanted me to join as a partner because, as our key investor said, ‘You move us from black-and-white to hi-def.’” Bittman found it a difficult decision. “You can never leave The Times ,” he recounts acquaintances telling him; “too many people are relying on you to say what needs to be said.” Bittman took the plunge because, he maintains, he could be his “own worst critic” which, however, is an assignment he has shown little inclination to accept. (“Harder Than I Thought”)

Bittman’s strain of confidence results in other strange expressions of self congratulation. During the process of writing How to Cook Everything Fast , he claims to have noticed “that most experienced cooks don’t work the way most recipes are written.” Those cooks, he thinks, prefer to multitask:

“They don’t chop an onion, measure oil and salt and chili flakes, mince a clove of garlic wash and dry and chop parsley, chop a tomato, put a pan on the stove, add the oil, add the onion, and so on. (Some do, of course; but they’re in the minority.)

Rather, they put a pan on the stove, put some oil in it, begin heating the oil, chop the onion and put it in the oil, and proceed from there.”

Bittman therefore “began writing recipes that way--a kind of prep-as-you-cook method--” and adopted it for the “untraditionally written” recipe cards in the Purple Carrot meal kits. A competitor, he claims, appropriated this ‘unique’ style, which he finds “both annoying and flattering,” an unwarranted assumption and further demonstration that with Bittman the ego is always at the wheel. (“All Things”)

Vanity, however, is not the problem posed by his description of the meal kit recipe format. What other format might Bittman have chosen? In a meal kit there is nearly nothing to prep; most of its contents arrive chopped and measured. Furthermore the process is a prescription for failure. If in fact a cook heats oil before chopping the onion, the oil is likely to burn before the onion eventually joins it. In addition, Bittman’s quaint notion that people can perform multiple tasks at the same time has been debunked by any number of studies.

On the subject of his ‘untraditional’ meal kit recipes Bittman is boasting about what amounts to nothing at all and, in the case of instructions for food that does not emerge from a kit, encouraging the entrenchment of improper practice. When confronted with customer “pushback” about the “unusual recipe-writing style” at Purple Carrot, however, Bittman responded with “You Can’t Be All Things To All People.” (“All Things”)

7. Back to Britain.

Back to the question of Bittman and British food, which, against the backdrop of social and political dislocation, is small beans. Small British beans are what we count at bfia, however, so bear with us if you have borne with us this far.

Bittman’s attitude toward British food, or absentmindedness about it in contextual terms, entails more than his apparent neglect. It turns out he likes to bake scones (and other things; he boasts that his sourdough measures up “against most anyone’s” ), and over the years has printed recipes at the Times for British dishes including devilled chicken, bread pudding and fools, although his are not distinguished renditions. (“What I’ve Been Up To;” underscore in original) Unlike most of what he cooks (or used to cook), Bittman does not note where most of the British dishes originate. Perhaps he is confused or does not know; perhaps he is afraid to frighten readers with the specter of British food. Either way the cuisine deserves its due the way he has identified the dishes belonging to the foodways of other cultures.

The contradiction that characterizes much of Bittman’s work does not arise from malice. He is, however, overconfident yet somewhat confused about the particularities of his cause, and the constant self-promotion does not help things. We would like to like him but Bittman has become Hawthorne’s reformer, unaware that his aspirations have led him astray.

Sources:

Mark Bittman, “A Farewell,” The New York Times (12 September 2015)

“Mark Bittman: Why I Quit My Dream Job at the New York Times ,” TIME (2 November 2015)

“The New Foodieism,” www.grubstreet.com (June 2017; accessed 22 October 2017)

“This is Gonna Be Harder Than I Thought,” www.fastcompany.com (18 November 2015; accessed 23 October 2017)

“What I’ve Been Up To,” www.grubstreet.com (June 2017; accessed 22 October 2017)

“You Can’t Be All Things To All People,” www.fastcompany.com (11 February 2016)

Jane B. Brody, “Good Vegan, Bad Vegan,” The New York Times (3 October 2017)

Heather Haddon & David Benoit, “Mark Bittman Adds Activist Investor to Resume in Whole Foods Campaign,” The Wall Street Journal (13 April 2017)

Richard Horgan, “A Strange Sequence of Events at Purple Carrot,” www.adweek.com (11 May 2016; accessed 22 October 2017)

Annie Nova, “Mark Bittman: Here’s Why Meal Kits Like Blue Apron Are a Waste of Your Money,” time.com (21 July 2017; accessed 23 October 2017)

Tom Philpott, “Mark Bittman Leaves Vegan Meal-Kit Company Purple Carrot,” www.motherjones.com (11 May 2016; accessed 20 October 2017)

Mimi Sheraton, “To the Editor,” The New York Times (21 September 2015)