Sea urchins from the stomachs of pigs, exploding chickens & lost food refound; the wide & wild British world of Dorothy Hartley featuring foraging.

1. An unlikely icon.

Food in England appeared in 1954, an unlikely year for the emergence of so significant a study. Rationing remained in place for fifteen years--it would be the final one--and for that and other reasons the popularity and reputation of British food had reached a nadir. Dorothy Hartley would have none of that. Her doggedness was prophetic, for her opus has remained in perpetual print.

Notwithstanding its name, Food in England is neglectful neither of Scotland nor Ireland, nor a comprehensive survey but rather a long (over six hundred fifty pages), loving and lovely meditation on traditional foodways. Miss Hartley has lots of recipes, some of them useful, some of them brusque, but their utility is almost beside the point.

2. The lady can write.

Consider some prose, about the medieval uses of a pig’s stomach, from a pair of pages. On pig haggis: “This is very good, especially if you like tripe. (In Ireland this was the gift to the labourer who helped with killing the pig.)” On Yrchins, or urchins: “Very colourful and mediaeval.” It is an apt summation, as Hartley’s own explanation of a Medieval description demonstrates:

“These are small haggises, filled with spiced minced pork, roasted, and then stuck over with split almonds and browned to a finish. ‘Sum,’” or some, “were to be made gold (dore) with a batter (of egg and flour). ‘Sum grene’ (chopped parsley) and some black (like blood puddings). With the white almond spikes they look like brightly coloured spiked ‘sea urchins’.” (Hartley 110-11)

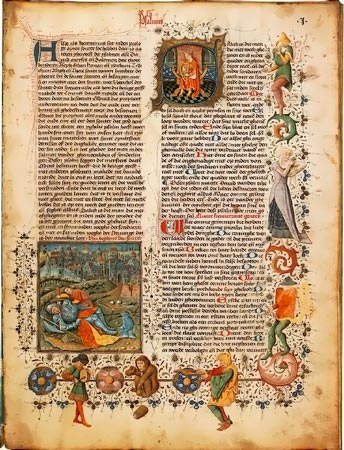

The introduction to the subject of blood pudding: “Probably the earliest pudding made and traditionally interesting. Every illuminated manuscript shows the winter pig-killing and the making of black puddings.” (Hartley 111) If it is not quite clear what Hartley means by ‘traditionally interesting,’ and if quite apparently not all manuscripts were either concerned or illustrated with butchery, those observations mean nothing. Clear, seductive writing like this renders any reader unable not to want the food it describes.

No pigs.

3. An explosive idea.

Then, at some remove from the stomachs of pigs, there is the narrative recipe for exploding chicken, “A Very Tough Old Fowl Exploded.” Miss Hartley did not pretend to have created any of the recipes she recorded, but did not disclose all her sources either, unfortunately including the one for the exploding recipe. “For this,” she advises her reader, “get the biggest and largest bird you can find. It does not matter how tough it is.” Choose the worst chicken imaginable, either for the obvious purpose of economy or perhaps to ensure a superior outcome. Through all of this comedy high and low combine.

It would appear odd that, apparently, nobody has remarked in print or online about this explosion. Nobody else has identified the recipe either, and ballistic recipes more generally are rare, although both Hannah Glasse (1747) and Elisabeth Ayrton (1975) offer versions of “Bombarded Veal” while the United States Manual for Army Cooks (1896) describes a “Bomb Shell” that may be made as either a “12-” or “32-pounder.” It is a classic British meat pudding (species unspecified), sometimes seasoned with Indian spice, “capiscums, fruit etc.” steamed in a cloth. (Ayrton 71-72; Manual 93)

Although entertaining, Miss Hartley’s recipe is a little opaque. After stuffing the chicken (“put a couple of onions inside”), she simmers it “very slowly overnight, letting it grow cold in the water as the fire dies down.” She soaks the old fellow for hours more in the cooled stock, relights the stove, gets her oven “fiery hot.” At this point the pace reverses and the cook needs to work fast. Lift the bird from the pot “the minute the water begins to boil, dredge it thickly with pepper and flour, and instantly shove it in the hot oven. Close tightly and leave it 10-20 minutes, according to size.”

That, as they say, is the dish:

“When taken out, the breast and skin should be brown, and crisp as if roasted, but the fowl still damp and juicy, inside. Scientifically done, it will almost fall to pieces when carved, as the steam from the boiling broth, superheated in the hotter oven, explodes, and, quite literally, blows the whole contraption to pieces.” (Hartley 187)

No sizes, however, are specified, and it is by no means clear how anything could turn brown beneath that crust or under the skin. Perhaps the reference to science, otherwise unclear, is but a general nod to the laws of chemistry, physics and its subset ballistics, but the nature of the explosion itself remains impenetrable. Does the batter spatter across the inside of the oven or only when insufficiently controlled by the culinary bomb squad? Whatever the answers, the preparation does bring to mind the ‘wild turkey surprise’ fashioned from a drum of dynamite stuck with two more ‘drumsticks’ of TNT that Bugs Bunny feeds to the Tasmanian devil.

One Wild Turkey Surprise, comin’ up!

4. Perpetual thrift.

Back to the subject of chicken we must look again for a bad bird. Miss Hartley notes of cockaleekie that the Scots

“have kept this fine old soup unchanged through the centuries. (I don’t like to think of what would happen to any foreigner who tried to tamper with Cockaleekie.)

It is not generally known that an old cock bird gets far more tough than any hen. The oldest cock is best for Cockaleekie,”

perforce the name.

The technique is something like the first phase of the exploding recipe: The soup is best “cooked over peats, put on overnight,” and should “simmer and simmer and simmer--and then simmer, till the bird is rag…. ” (Hartley 188) The reference to peat, fuel the Scots traditionally use to warm houses and dry malt for whisky, is typical of Miss Hartley’s attention to detail, while the repetition, and the image of chicken reduced to rags, could not be more eloquent.

5. Vertical cuisine.

She wrote other books on varied subjects with a similar idiosyncratic elegance, and should herself be the subject of a significant study, but one recipe from Food in England must suffice for immediate purposes. It is for a simple combination of apple, bacon and celery that unaccountably has faded from currency. Her description of the dish is typically idiosyncratic in its absence of cooking time or medium (stove? oven?). It does include some but not all proportions; equal weights of apple and celery, no qualification of bacon by amount or type, although given the era in which the book appeared we should assume Miss Hartley cooked this dish with lean cured but unsmoked pork from the loin or thereabouts rather than something smoked or not from the belly. The English then called the fattier bacon that is all we know in America ‘streaky,’ as many still do.

The version from Food in England is both curious and messy, unnecessarily so. For no real reason other, perhaps, than tradition (we are not told why), it specifies only windfalls, which would make an otherwise universally accessible dish unavailable to most people, even back in 1954. Applesauce made from the windfalls goes over a layer of bacon into a tall jug followed by upright celery stalks “until the pot is full (by this time the apple sauce will have risen to the top)” or, more likely, oozed all over the outside of the vessel. Only then must the hapless cook “[t]rim off the sticks level, and cover the top with these chopped ends and chopped bacon.”

“It is,” Miss Hartley insists, “the flavour running down the fibres that makes this dish. It is not nearly so good if the celery is cooked flat, therefore a deep-sided stew-jar or jug must be used.” (Hartley 385)

6. Forage if you must and resort to the horizontal if you may…

Her advice in this respect is unsound, as Richard Mabey, who revived the recipe with The Full English Cassoulet in 2008, infers. His book emphasizes thrift and therefore extols foraging, the dubious rationale--windfalls again--for the recipe.

It is no coincidence that Mabey chose a Hartley recipe. In charting his literary influences, he discloses that

“Dorothy Hartley’s epic Food in England had the deepest effect on me. Hartley was a pioneering woman journalist, an instinctive anthropologist, and she’d wandered England between the wars, recording customs and practices in ordinary houses and farms. The techniques and recipes in the book are extraordinary for their vividness and ingenuity, and have the authentic tang of the home kitchen.” (Mabey 17)

An accurate assessment.

Mabey dutifully and properly gives Miss Hartley credit for reviving the windfall recipe, paraphrasing hers with some welcome detail and a handful of tweaks. He gives weights for the apple and celery; specifies four rashers; adds clove, muscovado sugar and a little water when making the applesauce; calls for cooking the dish in the oven at a specified temperature for a specified time; and notes that his proportions will serve two, “as either a starter or a vegetable with pork or lamb.” At the end of the recipe he adds the dollop of common sense: “If you don’t have a suitable tall cooking-jug, simply follow this recipe using chopped apple and celery in an ordinary casserole dish.” (Mabey 141)

7… but go easy on the terdiles.

Mabey does not suffer from insecurity. He claims “a kind of culinary perfect pitch, an instinctive sense of what goes with what before you’ve actually tried the combination.” Nor, however, does he lack a certain humility. He admits he never mastered the “exquisite efflorescence,” nice writing there, of Yorkshire pudding and happily notes that his attempt at growing a sixteenth century salad ball of seeds surrounded in a “terdile,” or shitball, met with limited success. He had made the

“terdiles out of horse manure, and drilled in a mixture of various lettuces, rockets and radish…. The dung was plainly too rich, the seeds too numerous, the different species programmed to grow at very different rates. Just a few of the nitrogen-hungry lettuces made it…. ” (Mabey 14, 15, 44, 45)

8. Searching for the British bean dish.

Ironically the innovation that gives his book its title represents another unsuccessful attempt. The guiding premise:

“The cooking of beans with various kinds of meat is popular in vernacular cuisines across the northern hemisphere…. Britain, alas, seems to have had no such national bean and pork dish--though we enjoy tinned baked beans with bacon and sausage, especially at breakfast.” (Mabey 102)

Fair enough, although Britain does have some similar if regional as opposed to national things, including the lamb and barley stews long linked to London. Not of course based on beans but a kindred concept.

The same may be said for the Cumbrian Tatie Pot described by Jane Grigson in English Food, an imaginative and wonderful dish deserving of revival. It takes barley along with assorted pulses rather than beans and combines them with beef, lamb, onion and black pudding under a roof of biggish potatoes quartered lengthwise. Variants, however, do include beans instead of the pulses, including a version from Shetland that omits the beef and adds carrot. “Tatie Pot,” Mrs. Grigson explains, “is very much a dish of communal eating, at village get-togethers, or at society beanos, rather as baked beans are a standard item on similar occasions in America.” (Grigson 220; 60 Degrees North)

Other, beany, candidates for comparison to cassoulet were chronicled over four decades ago by Elisabeth Ayrton in The Cookery of England, which Mabey unaccountably has overlooked.

“Beans and Bacon,” she explains,

“was a traditional English cottage dish, but it was also a favourite in the great houses, where in the early summer a side dish known as Beans and Collops often featured at sixteenth- and seventeenth-century feasts.”

The version made with bacon was based on fresh broad beans, a British obsession, had highlights of clove, brown sugar and red wine, and was bound with “good parsley sauce or melted butter with a little chopped parsley and savory in it.” (Ayrton 350) In context ‘melted butter’ is not merely butter set on heat but rather the universal sauce of eighteenth century England, an emulsion akin to Dutch, or hollandaise, sauce.

Mrs. Ayrton also identifies two dishes based on dried beans, “Baked Beans” cooked with cubes of ham, onion and golden syrup, a dish the Puritans would bring to Boston in the seventeenth century and slowly transform into the style of New England known today; and “Pot Baked Beans” with bacon, treacle and mustard, a medieval palette of savory, sweet and heat essentially indistinguishable from the New England staple. (Ayrton 351, 352) Peas also were cooked with bacon in Cornwall during the early nineteenth century. (Ayrton 365)

The Boston version

Mabey fails to reach his goal of creating “a cassoulet adapted for British ingredients.” Like the “Beans with Bacon” that Mrs. Ayrton unearthed, his recipe uses “freshly podded beans,” which as noted is British enough, but among his elements are garlic, olive oil, tomatoes and white wine, hardly the foundation blocks of British cuisine.

Better to follow our lead in creating a British bean dish made with bacon, oxtail, carrot, celery and onion, sauced with stock and stout. Use big white beans, either butter or cannellini, and simmer beyond what otherwise would pass for an excessive amount of time; oxtail recipes never specify a long enough time.

Best, however, would be another recipe recorded by Mrs. Ayrton, hiding in plain sight because it does not appear under ‘beans’ in her index. “Casserole of Game with Beans” was, she explains, “[s]erved as a luncheon dish at the Garrick Club in the nineteenth century.” As usual she provides a story to support the recipe:

“A noble member is supposed to have said, ‘It’s the beans make the bird.’ ‘You mean, replied another, ‘It’s the bird makes the beans.’” (Ayrton 190)

The casserole in fact calls for “bird or birds” marinated in red wine (you might use ale or, even better, porter) with bacon, carrot, onion and herbs, then treated to mushrooms and a roux with a dusting of chive and parsley. Mrs. Ayrton uses dried butter beans; you could use any bean at all. This, after all, is the English cassoulet, or perhaps cassoulet is the French Casserole of Game with Beans.

Sources:

Elisabeth Ayrton, The Cookery of England (London 1975)

Hannah Glasse, The Art of Cookery made Plain and Easy (London 1747)

Dorothy Hartley, Food in England (London 1954)

Office of the Commissary General of Subsistence, United States Secretary of War, Manual for Army Cooks (Washington DC 1896)

Richard Mabey, The Full English Cassoulet: Making-do and Other Improvisations in the Kitchen (London 2008)