Our first monthly miscellany, being a book of surprises.

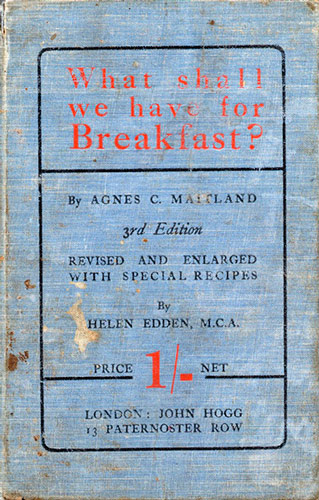

From the dusk of Victoria’s reign past the Edwardian interlude, the London publisher John Hogg issued a series of cookery books costing a shilling apiece. Among them is What Shall We Have For Breakfast? or, Everybody’s Breakfast Book written by Agnes C. Maitland and expanded in 1912 after her death by Helen Edden.

By then each author trailed a string of accomplishment. Miss Maitland had written several novels, a collection of stories for children and two cookbooks in addition to What Shall We Have. In 1889 she became principal of Somerville Hall, at first a women’s adjunct to the University of Oxford.

During her tenure, Miss Maitland introduced the tutorial system to Somerville and encouraged her students, all female of course, to embark on undergraduate degrees. By 1881 Somerville had been incorporated as a college within the university; by 1894 it had become a genuine college in its own right rather than just a residence hall, and had adopted the name Somerville College. To its abiding credit, Somerville was nondenominational from its founding.

These achievements are all the more remarkable because her father, a Scottish merchant removed to  Liverpool, had her schooled at home in a parochial Presbyterian abyss. ( ODNB )

Liverpool, had her schooled at home in a parochial Presbyterian abyss. ( ODNB )

Miss Edden lacked the glittering prize of a position at Oxford but possessed the greater gift as a writer. Her cookbooks, especially County Recipes of Old England , are concise, clear and delightful. County Recipes has the additional appeal of whimsical little line drawings interspersed within the text.

Miss Edden’s research skill must have been formidable, for she found recipes that remain unpublished anywhere else. They have been cited with approval by historians of local English foodways and followed with success by cooks interested in preserving them.

One such recipe, for gingerbread, ought to be a runaway favorite worldwide. It is a white gingerbread made with only flour, butter, separated eggs, baking powder and a whopping proportion of ginger, a tablespoon for every cup of flour. The original tastes even better dosed with a hefty shot of midbodied rum, like Westerhall’s but that does not detract from the quality of the teetotal formula.

To return to Miss Maitland, notwithstanding her stature as principal of an Oxford college, and pathbreaking belief in university education for women, she retained a lifelong interest in the domestic economy of the people, as the inclusion of her breakfast book in a series that cost but a shilling demonstrates.

Thirty-five years before the initial publication of What Shall We Have , the peerless Alexis Soyer had written A Shilling Cookery for the People in 1854. It was his foray into food for the working class following his two upscale cookbooks aimed at rarified society and then the teeming English middle classes. There was nothing aspirational about A Shilling Cookery : It really was aimed at the poor and offered practical yet imaginative advice on utilizing modest ingredients including the cheapest cuts of meat.

Everybody, it seems, and not just the working class, bought a copy of A Shilling Cookery, which, at literally a shilling, cost only something less than £3 in terms of current currency. (nationalarchives) It was a runaway success: A quarter of a million copies had sold by 1867. (Cowen 250)

What Shall We Have is remarkable for the increased range of ingredients that, apparently, had become affordable to those of middling or lesser means in Britain on the eve of the First World War. In addition to the usual suspects, at least on British breakfast tables, of bacon, eggs, kidney, marmalade, potted meats, smoked fish and the like, three manifestations of chicken, two of partridge, a collared calf’s head, lobster quenelles, “Yorkshire collared beef (two ways)” and other surprises inhabit these pages.

Miss Edden’s “Additional Recipes” include a glazed beef roll, tomato sauce (but for saucing what? She does not say) and Scotch eggs, latterly the province only of public houses.

Perhaps Miss Maitland’s selections remained atypical; her preface starts with the accusation that “[i]n most English middle-class households breakfast of all meals is the most uninteresting.” (Maitland vii) If she was right, the myth that the only decent meal in Britain began the day may be unfounded.

That would amount to another surprise. Equally surprising is the presence of pies in What Shall We Have? Miss Edden’s is the most unusual, made of calf’s head, while Miss Maitland’s three raised pies add a ‘French’ one to the traditional pork and game iterations, even though savory pies are, and were, essentially absent from French tables.

It is not possible to discern anything at all French about her “French Raised Pie,” other than the omission of her game pie’s ineluctably English spicing of cayenne, nutmeg and mace. Other than that, the French pie is basically a shorthand edition of the game pie itself, with the addition of equally English pie ingredients in the form of ham and optional mushrooms.

The biggest surprise, a double dose, of What Shall We Have must be its demolition of any distinction between breakfast and any other meal other than its omission of sweet dishes. No sweet cakes, sugar laden cold cereal, chocolate croissants or jelly doughnuts. Even when it came to preserves, the style of choice was marmalade, least sweet of all the sugar based spreads. Breakfast in England at least through the Edwardian era was a savory, not sweet, affair, and that sets things apart not only from other nations but from our own time too.

As for the book itself, What Shall We Have For Breakfast? was in reality a good source for a limited number of savory recipes and also good value at the equivalent of only something under £3 a pop in its time. An added bonus; “Tea-Making,” the instruction how to brew a good pot of tea, is timeless. It appears in the practical.

Note:

-According to Miss Edden, “Vermicelli may be used instead of breadcrumbs” to cover the sausage coating on the Scotch eggs, “giving the appearance of birds’ nests, which latter name would then be given to the dish.” (Maitland 98) Another surprise.

Sources:

Ruth Cowen, Relish: The Extraordinary Life of Alexis Soyer, Victorian Celebrity Chef (London 2006)

Helen Edden, County Recipes of Old England (London 1929)

Enid Jones, “Maitland, Agnes Catherine (1849-1906),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford 2004)

apps.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency/results/asp#mid (accessed Trafalgar Day, 21 October 2014)

Alexis Soyer, A Shilling Cookery for the People (London 1854)