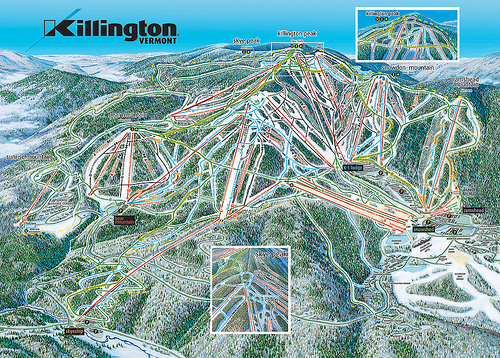

Ski the east

An end of season miscellany

It would be fatuous to contend that ski country in the northeastern United States is a cauldron of British cuisine. Heavy pastas, sodden nachos, burgers and wings, steaks and fries blanket the ground more thickly than in mallworld. There are lots of seventies holdouts like salad bars and ‘continental’ menus too. Some of this is good, which is a bit of a surprise but for the rustic ethos of the mountains, but most of it is bad. It is not even campy; you do not have to bother too much if your customers are tired, even dazed, after hammering a mountain, have been guzzling booze (more dazed) and are unlikely to return in any event.

Within this generic American landscape, however, lurk some unforeseeable British outposts. This is not to claim that an authentic British restaurant hides in either the Adirondack or Green mountains, but rather only to note that British dishes, or at least British influences, pop up on menus once in a while. During this past season we found a few of them at restaurants both casual and formal.

The road up to Killington from Rutland, Vermont, is a wasteland of ‘family’ restaurants, unjustifiably famous bars and meat markets--pickup joints, not butchers. In fact, decent food shopping is hard to find, even down in town. McGrath’s, the landmark Irish bar/restaurant/Inn across from Pico that, in reality, is about as Irish as the Editor, has been notably unfriendly and unpleasant on our visits there. Do you enjoy a whiff of vomit spiced with industrial disinfectant? If not, skip McGrath’s.

Farther along the access road you will find an alarming looking building aptly named the Wobbly Barn. It is perhaps the epicenter of rowdy Killington nightlife; one ski magazine wonders why anyone would go somewhere else. There is mostly mediocre live music most nights, but that is not a problem. The place can be fun. It has a steakhouse in the cellar that is dark and woody. A big fireplace fronted with benches dominates a wall past the bar and high booths build the cozy, lodgelike atmosphere. This dining warren is a little careworn which does nothing to diminish its charm.

You descend into a sort of chapel to excess where ‘salad bar’ is taken to extreme with lots of items to pile onto platters along with bowls of hot soup and little loaves of hot bread. This food line comes with every entrée, which of course mostly means steak; our ribeye, served properly on the bone, was perfectly grilled and surprisingly good. Here come the promised British elements, a soup of curried chicken and an order of quail. The soup was more of a stew and was a welcome starter after a frigidly exhilarating day on the mountain.

The Wobbly Barn

Killington Road,Killington, VT

802-422-6171 www.wobblybarn.net

Quail is not exclusively British, and technically is not game, but its flavor decidedly is, and nobody likes game, or makes so much of it available to consumers, as the British. The quail at the Wobbly arrived with a blueberry sauce that had caused some trepidation when we saw it on the menu, but it reminded us of Cumberland sauce, no bad thing. The dish was delicious so somebody in the kitchen knows how to roast little birds. Somebody in the dining room knows her business too; our waitress was efficient, personable and professional. There are Vermont beers on tap and a passable wine list. We would return.

Away from the screaming lights of the Killington access road, down a dark valley, lies Hemingways, a most serious establishment. At this point it is worth noting that on 28 March, The New York Times described Vermont as “a locavore’s paradise,” while conceding that the state lacks the slaughterhouses to dress the animals grown there for meat; exiles from Manhattan do not like the idea of killing animals nearby for the local cuts they crave. As a result, strapped farmers need to transport their animals to abbatoirs as far as 300 miles away, at considerable cost and to the distress of many otherwise needlessly confined animals. ( Katie Zezima, “A Push to Eat Local Food Is Hampered by a Shortage,” NYT 28 March 2010) These people are beyond self-regarding to the point of narcissistic self-delusion. This digression is no irrelevance; it dramatizes the lengths and expense that a principled place like Hemingway’s needs to go in a fractured polity like Vermont to adhere to its own, high, self-imposed standards. The place indicates that Vermont restaurants finally are catching up with the quality of the state’s suppliers, if not always slopeside.

The small, dark bar at Hemingway’s leads to a bright and elegant dining room. Somebody paints, and if the pictures are more exuberant than accomplished, they are welcome. The proprietors must spend a fortune on flowers, and the big tables are napped with good fabric and spaced widely. Expense is not spared; costly ingredients are sourced locally and the service is leisured, almost courtly. The atmosphere is hushed, formal, but if this is not an exuberant place it is not unfriendly either.

Hemingway's

4988 US Rte 4, Killington, VT 05751

802-422-3886 www.hemingwaysrestaurant.com

Do not expect good local beer. Hemingways is one of those old school sillys that seeks to showcase its cuisine by offering only two choices (the Amstel light does not, cannot count) and those are bottled, but at least one of them is Pilsner Urquell. On to the food, which is faultless from the amuse bouche to the house made desserts. The restaurant likes game (partridge, pheasant, quail and rabbit) and crab, it likes pies (chicken and rabbit) and it does ‘import’ impressively fresh fish from the east coast. These predilections could have been designed to please the Editor and her companions at Hemingways. All we needed was a draft IPA.

At this point it only is sporting to muse that Hemingways might well be surprised, and possibly horrified, to learn that britishfoodinamerica regards its food as inflected with British tradition. Perhaps the influence is subconscious but it is palpable. A pot pie always seems to appear as a starter, and the restaurant could argue that the dish springs from regional tradition, but here as opposed to elsewhere (chowder, cornmeal, squashes and the like) the tradition had been transported, if only because the British predilection for the savory pie predates the existence of an eponymous New England.

This was an excellent pie. Previously, in ‘Things We Like,’ bfia has appeared metaphorically nude to our public by confessing an enthusiasm for frozen puff pastry. Hemingways has tried our conviction. Theirs is a flaky and soothing sheen of the best butter and unlike anything else anywhere. The treatment of the filling is a little unorthodox, would not work as a main dish and sparkled as a starter. Sometimes the pie is chicken; ours was rabbit. The meat was succulent rather than stringy and the vegetables firm, which would have become annoying in a full portion but set a nice, crunchy tone in the size of a starter. As the nuance here indicates, this is a kitchen with preternatural self-awareness.

Pheasant, so hard to cook without drying, was flawless; so was the quail. Partridge is served with that most British dish, a pudding--in this case of brioche, but then British cuisine is promiscuous and always has borrowed from abroad. We wonder aloud here why partridge is so seldom sighted on American menus. It is relatively mild, so should not frighten the provincial; unknown to most home kitchens; and easy to cook. It would seem like an ideal restaurant item.

Everything, from the complimentary crabcake and the fish dishes we ordered, to the vegetables and house made desserts, was memorable at Hemingway's. The wine list is long, interesting and terrifying in its price points but a tad Potemkin; our first three selections would have been interesting but were unavailable so we ‘settled’ on a lovely and appropriate 2007 WillaKenzie Pinot Noir. Hemingway's is brutally expensive and worth the cost.

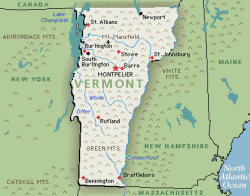

Farther north in the Mad River Valley the atmosphere is different. If Killington often feels like a Long Island suburb, then Waitsfield almost feels like Vermont. Sprawling, elegant, professional Sugarbush and the eccentric timewarp at Mad River Glen each is a legitimate destination with compelling terrain, and together they anchor a dining and shopping scene that so small a town otherwise would not support.

There is a bookstore, The Tempest, with a small but quirky and surprising selection. A a charming bonus, big Lionel trains circuit the shop on a narrow and dedicated mezzanine just beneath the ceiling. A nice food section includes both Fergus Henderson’s cultish Nose to Tail Eating and several titles by Elizabeth David. When the Editor asked whether the store found customers for these books, the aging, hippified clerk smiled wanly to explain that, no, they are stocked only because the owner likes them. At least, however, they are stocked.

We ate dinner on a frigid Monday night at Egan’s Big World, a big room faced in raw lumber with a high, exposed structural peak. It was so quiet that some of the kitchen staff had taken stools at the bar to pass the time watching Gordon Ramsey eviscerating the owners of an exurban English pub. One of the staffers was intently, playing “Pole Dance Hero” on a laptop.

Egan's Big World

Rte 100 & 17, Waitsfield, VT

802-496-3033 www.bigworldvermont.com

The staff who were working were all women, an all too common state of affairs; they are the more reliable gender. With the exception of our icy waitress, the women were patient and personable despite some provocation from the sparse crowd; this is the kind of place where tourists appear to demand menus and ask questions of the maitre’d before leaving for a greener pasture or parking their ill-mannered children at a separate table for de facto babysitting. The place showed good judgment too; they had fired a (male) bartender whose hostility on a prior visit nearly precluded our return. There are a couple of good organic IPAs on tap and a good selection of other beers.

Food at Big World is conventional enough for ski country; burgers, soups, wraps and vegetarian preparations dominate the menu but they are executed well. There is, however, another side to the open kitchen. A confit of duck was deftly seared over a wood fire, and venison in a simple wine reduction was perfect, rare as ordered and tender as hoped for. The kitchen did the impossible with winter squash; it was light and nuanced, and we liked the accompanying mushrooms too. This was one of the better and cheaper venison dishes that the Editor, who seeks out game, ever has tasted, and she had found it lurking amongst the good bar food.

The short wine list skewed to basic California choices offered good value, including a Cline Zinfandel at a fair price.

In contrast, the celebrated Pangaia restaurant down in North Bennington was a disappointment. We also were there on a bleak Monday, when the more ambitious dining room was closed but the bar served its usual items. There were some British standards that sounded appealing but were not. Everything we ordered was clumsy stodge, nothing unexpected in rural New England but not what we expected here. It was, however, a Monday, perhaps the chef was off and we will reserve judgment.

Over the border in Lake Placid, a few good restaurants serve a number of good game dishes but the wonderful Olympic town and its mountain, Whiteface, deserve their own essay at some point.

Domestic cooks in New England still reflect a vestigial British influence compared with their counterparts in the Middle Atlantic states; you always can find parsnips, suet or lamb, and usually can find smoked haddock, a hopeless quest in much of metropolitan New York. Nonetheless it was a little surprising to find these fleeting murmurs of British foodways in Yankee restaurants.

***

The dominant British voice in ski country, however, says beer. Like craft brewers across the United States, producers in both upstate New York and Vermont have mastered British styles. The ales tend to be best but some of the porters and stouts are excellent too.

The Brewer's Dray

Saranac is the upmarket brand of Matt beer, a relatively large small brewer based in Utica. Matt beer is bad but Saranac is better, if nothing special. The beers are decent but thin and bland, and do not resemble honest craftbrews. The IPA is barely hoppy and either does not keep or sell on tap; our samples of it frequently are stale. These beers are much like the ‘niche’ products, like Budweiser American Ale, timidly produced by the national giants in pale imitation of genuine traditional styles. There is some, diminished, resemblance to the real thing but the flavors pall fast.

In contrast, the Lake Placid Brewery produces some of the best beer in America right now. Placid brews its draft beer onsite at its public house, a converted church on Mirror Lake; bottled beer originates from a bigger plant and bottling line in Plattsburg. Unlike some small brewers, Placid’s bottled beers do not have a big dropoff in quality; they are not as good, but bottled beer never reaches the heights of well-tended draft, and Placid’s bottles are good indeed. Their iconic brew is Ubu (named for a dog rather than the Jarry play), a rich and malty ale in the same style as the equally good, but lighter and perhaps better balanced, Hampshire ale made in Portland, Maine by Geary’s.

Placid produces a good strong porter too, but their best brew is Frostbite IPA. It is big and bitter, strong but not as strong as Ubu, and has the hoppy finish essential to a special IPA. We usually prefer citrusy notes, and although they do not show up to finish a draught of Frostbite, it is so good that we do not care. Its brilliant competitors include Dogfish Head Sixty Minute Ale (from Lewes, Delaware), Six Point Bengali IPA (Brooklyn), Trinity IPA (Providence), Victory Hop Devil (Downington, Pennsylvania) and the IPA from Yard’s in Philadelphia. It is fair to claim that these stunning IPAs eclipse both the competition from Vermont and their antecedents brewed today in England.

We probably ought to note that none of these ales is one of those ‘extreme’ IPAs that are built to pack as much alcohol as possible by some hormonally competitive brewmasters. We do not consider the extreme beers IPAs at all: They most closely resemble unwieldy and unbalanced barley wines. It is a mystery why examples of the breed like the Dogfish 90 Minute Ale win so many awards, but then alcoholic jam bombs from Australia and California tend to win wine tastings too. If required to guess the reason, we would speculate that palates numbed by hours of sipping and note-taking relish a change; the biggest if not best flavors register most after a time Context is everything, however, and nobody who likes beer drinks it only in the context of a tasting.

The Placid brewpub is no secret, and the crowds can get painful at peak times, like long weekends during ski season, both because of the crush and because newbies can get extremely zonked on beer that is considerably more alcoholic than the norm. These unfortunates linger long; some of them pass out unnoticed by their sodden tablemates. The food is mediocre but passable enough, and includes ‘pub’ standards like bangers & mash, fish & chips and sometimes ‘shepherd’s pie’ but made with beef, so that it would not really belong to a shepherd at all; it is, properly, a cottage pie instead. Staffers are generally nice, and you can get growlers to go. Go.

Lake Placid Pub & Brewery

813 Mirror Lake Drive, Lake Placid, NY 12946

518-523-3813 www.ubuale.com

Vermont beers do not match the ones from Placid, but the bar set across the New York line is high. Some of the Vermont craft beers are both interesting and good, just not as good. Long Trail is the least satisfactory. The brewer reminds us of a better Saranac. Their beers are decent, and bars seem to tend them better (except, again, for the IPA, which goes off even faster than Saranac’s), but these drinks, too, lack conviction. When it is not stale, the IPA along with the Double Bag (a meeker Hampshire or Ubu) are Long Trail’s best bets.

Otter Creek stands a rung above Saranac or Long Trail, but most of their beers have similar problems. We particularly dislike their flagship Copper Ale, more an Austrian than a British knockoff, and not a good one. Somehow it manages to taste metallic, both harsh and bland. The Stovepipe porter, however, is an authentic enough rendition, particularly on tap; a good session beer worth seeking out.

Vermont’s best ‘big’ brewer (these things are most relative; the state’s entire annual output probably does not match a day’s production from Anheiser-Busch) is Magic Hat located off an ugly commercial strip in suburban South Burlington. Number Nine, an ale inflected with apricot, is widely available on tap throughout the northeast; Magic Hat’s other draft beers are virtually invisible, but bottles its many beers are widely available at least as far south as New Jersey. Lucky Kat, a replacement for the brewer’s previous Blind Faith, is excellent, even though the pleasantly bitter finish lacks any citrus finesse. It is the best Vermont IPA that we were able to sample, and the only one hoppy enough to resemble the traditional style; Fat Boy is a refreshing pale ale for summertime. There is a decent porter among the other styles too. The Magic Hat website is one of the more imaginative and enjoyable, if not navigable, ones on the net.

Trout River, in Lydonville, Vermont, brews what might be a good example of red ale, Rainbow (get it?) Red. We do not like red ale. It is an Irish variation on the English bitter model that has virtually no evidence of hopping. If red ales had a hoppy tone they would taste better, but then they would be true bitters and not red ales. They do not resemble the weak, light mild ale style that clings to life in the north of England, however; they taste like candied ale with a cloying finish and do not refresh the soul and palate like a decent mild. Smithwick’s is a national brand in Ireland and the worst example; Rainbow Red is not as bad but it is nothing that we would choose. Trout River’s Scottish ale is a good version of the traditional heavy bitter, but although it is better than red ale, we are not particularly partial to heavy either.

Trout River also brews Hoppin’ Mad, a IPA that is much, much too timid. In essence this is a bland example of a traditional light ale. Please do not confuse light ale with ‘light’ beer; it is a legitimate style, or styles, one distinctive to England and the other to the United States.

To our tastes, an English light ale is (or was; like mild, it is getting hard to find) much like pale ale; the styles are contiguous and bleed into one another. They were brighter than bitters. In past times, one brewer’s relatively strong light ale might resemble another’s relatively weak pale ale and so on. The color and alcohol content were lighter; the beer’s dominant purpose was refreshment without insipidity.

In the United States, we tend to equate light ale with cream ale, a distinctively American style the color of lager. It has vanilla notes and a round, sharp finish. Genesee Twelve Horse, which is surprisingly good, and better than their perfectly decent standard version, is an exemplar of the style. What may be our favorite Vermont brewer, tiny Rock Art, makes an excellent one too, Whitetail Ale. They brew it with some wheat and yet it works (we do not much like standard wheat beers either). There are not many other surviving cream ales out there.

Rock Art started out in the cellar of its principal and brewmaster. It has moved to a bigger, tiny spot in tiny Morrisville, Vermont, and produces only a few thousand barrels a year. The name comes from petroglyphs that the brewer used to search out while hiking in Colorado; the brewery logo is an image of Kokopelli, a sort of Amerindian Loki without the dark side. Rock Art makes a dark, hefty winter ale, Ridgerunner, that packs a delicious alcohol wallop, along with three IPAs and fourteen other beers. Some of the IPAs, while good, are ‘extreme’ beers, and we have been unfortunate in failing to find a bottle of Rock Art’s traditional IPA anywhere from Bennington in the south to Stowe in the north. We will need to visit the brewers in Morrisville. The nice people at Rock Art grow their own hops.

Switchback is another microbrewer, located in Vermont’s ‘big’ city, Burlington. Since its inception in 2002 it has brewed a single beer, until now. It had been a while since we tasted the original beer, an unfiltered ale that resembles a southern English bitter with a heavier, almost Belgian inflection. It is a wonderful beer, better than we remembered, almost casklike in texture and tone. This, however, is no session beer; after a couple of pints the beer feels a bit thick and begins to need more in the way of hops.

Switchback has begun to brew a seasonal beer; first up, this winter, is a big, heady porter. In keeping with the style of the original unfiltered ale, this too is a relatively heavy variant on a traditional style, in this case veering toward stout in taste and texture. It too is superb if not wildly refreshing; we prefer it to the original ale. The brewery refuses to disclose its next seasonal special.

Along with Idaho, Maine and Washington, Vermont is one of four American states with the highest craftbrewing capacity per capita, but on balance the quality of Vermont beers, while good, does not quite match the best ones produced elsewhere. Nonetheless they are worth seeking out and supporting; the work of these personable brewers in helping to revive British beer styles in the United States is entirely worthwhile.