A first note from our own Curmudgeonly Raconteur

or Another source of food from the shell: The problematical whelk

Looking round for whelk information on the internet [Editor’s note: Please refrain from asking why, for the Raconteur can be an enthusiast, if sometimes a slightly scattered one, and to be fair some things take on lives of their own, a phenomenon found with particular frequency online] I came across an enticing blog written by one ‘Shuku’ from Malaya [Editor’s note: Our Raconteur intends no postcolonial disrespect in this imperial usage of ‘Malaysia;’ it is just that he is rather hopelessly Old School and it is best to humor him when possible] back on 20 November 2006.

Looking round for whelk information on the internet [Editor’s note: Please refrain from asking why, for the Raconteur can be an enthusiast, if sometimes a slightly scattered one, and to be fair some things take on lives of their own, a phenomenon found with particular frequency online] I came across an enticing blog written by one ‘Shuku’ from Malaya [Editor’s note: Our Raconteur intends no postcolonial disrespect in this imperial usage of ‘Malaysia;’ it is just that he is rather hopelessly Old School and it is best to humor him when possible] back on 20 November 2006.

‘Shuku’ wrote:

“Whenever I'm stressed, I buy a bowl of whelks to eat with lunch. I bought some today. There is a little cafe near the hospital where I work [presumably in Kuala Lumpur?], called the Bawang Merah (Red Onion) which sells the most delicious whelks in curry sauce I've ever tasted. I usually wind up with my mouth on fire after eating them, but it's worth it.

These tiny little shellfish, usually no bigger than half my thumb or a little longer, take some skill to eat because basically we have to suck them out of the shell without the aid of pins or forks - the tines are too big to go through the small hole at the end of the shell anyway. As the process involves generally a minute amount of rather strange sucking noises reminiscent of tentacle monsters sucking out eyeballs, a reasonable amount of tolerance amongst the diners in the cafe is usually a good thing, plus the ability to be thick-skinned and pretend to not notice when a particularly loud slurp brings all eyes in your direction.

Whelks take time to eat. I only order them when I have a long, leisurely full lunch break because they can't be enjoyed in a hurry.”

Now I admire Shuku and like her style but do confess that when personally stressed I may on occasion prefer to turn to the odd pint of beer, glass of gin, dram of whisky or bottle of wine, but no matter, the subject was whelks, which pair very nicely, thank you very much, with one of those improved Muscadets that have appeared at reasonable, not to say bargain, prices of late. If France can relaunch a downtrodden wine, then britishfoodinamerica may succeed in my current campaign, which I shall describe when appropriate.

In the event, the curried way of the Onion is not how whelks are eaten in the United Kingdom. In Britain whelks traditionally are served either precooked and shelled, dosed in malt vinegar and accompanied by a slice of buttered brown bread; or simply raw in the shell. Until quite recently it was possible to buy whelks along with the tastier cockles and winkles from men in white coats [Editor’s note: but not those from The Home] who would go round the pubs on Friday and Saturday evenings, and most seaside towns still have a shellfish stall on the waterfront. For some reason, some people find a mouthful of cold rubbery whelk a bit much and sales are falling, so the whelk requires a public relations and gustatory relaunch in Britain. The curry from the Bewang Merah, if sketchily outlined for the cook, is not a bad start but its sole example is hardly adequate to my campaign.

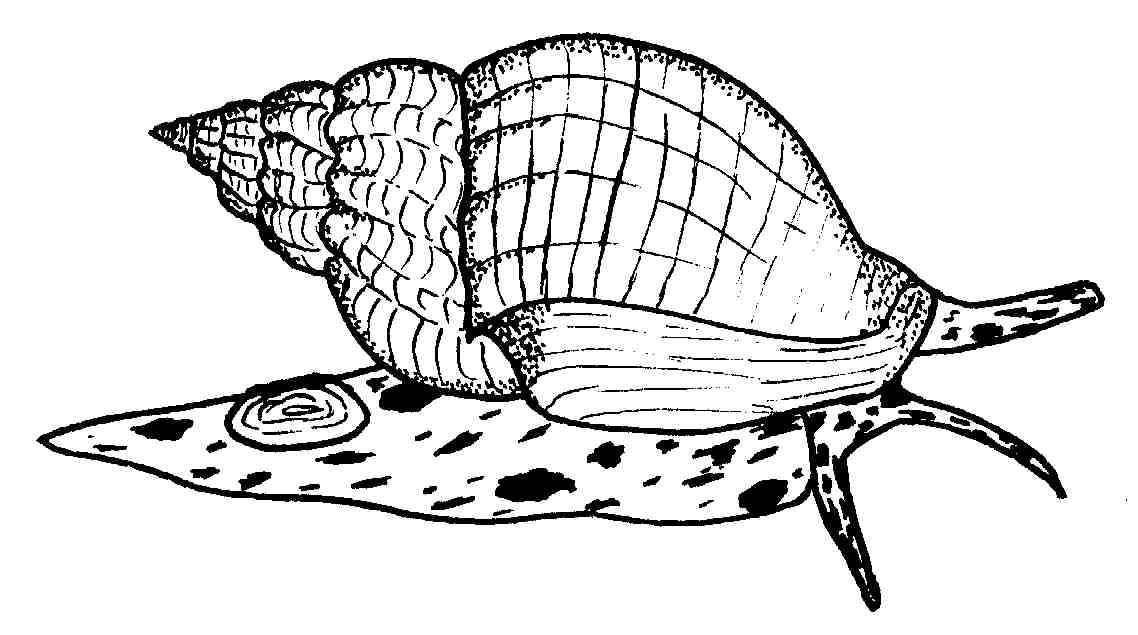

Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall has declared in his huge and wonderful book River Cottage Fish Book (London 2007) that he, too, is on a mission to lead a revival of interest in what he describes as “these chunky, humble sea snails.” I got there first, but no matter, he seems a well-meaning fellow. His recipes for Whelk Fritters and Thai Whelk salad look brilliant, sound brilliant--and do work, like most of his other recipes, although the fritters themselves do not taste particularly whelkish, which may go some way to account for Fearnley-Whittingstall’s claim that the “recipe has been known to convert even the most diehard whelk sceptic.” (Fish 328)

Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall has declared in his huge and wonderful book River Cottage Fish Book (London 2007) that he, too, is on a mission to lead a revival of interest in what he describes as “these chunky, humble sea snails.” I got there first, but no matter, he seems a well-meaning fellow. His recipes for Whelk Fritters and Thai Whelk salad look brilliant, sound brilliant--and do work, like most of his other recipes, although the fritters themselves do not taste particularly whelkish, which may go some way to account for Fearnley-Whittingstall’s claim that the “recipe has been known to convert even the most diehard whelk sceptic.” (Fish 328)

Fergus Henderson does not include a whelk recipe in either of his cookbooks because he hews to the simplest tradition and cooks them briefly if at all in his restaurant, St. John. His whelks can get big, much bigger than the ones described by my new and distant friend Shuku. They resemble a fist more than a fingerling. They are fresh too, indeed react as if living and lively. While Henderson’s sourcing here is as estimable as it always is (How can a simply boiled potato taste so intensely of… potato?), it also is problematic for the weak or squeamish: These whelks seem to fight back. As you pull at a whelk with the little lobster fork thoughtfully furnished with each order, it pops back to its shell. Sometimes the diligent diner requires several attempts to remove the squiggly blob from its shelter and, alas, the result does not seem worthwhile, at least in relation to the bigger, plumper individuals, who personify the cold, rubbery tradition that triggered my relauching campaign to begin with.

At this point it would seem wise for me, humbly, to retreat to my original program, which I should have disclosed requires heat, not only of the capiscene kind described by Shuku, and most certainly also the intemperate kind found in oven and on stove.

I should also note what I find obvious in any context, if obversely so here, for in the matter of whelks, size most certainly matters and as the Greeks of antiquity if not certain contemporary film producers and websites believe, smaller is better. I am no rogue here; Fearnley-Whittingstall himself provides his reader with the gentle warning to use smaller whelks, unless they are for chopping into his fritters.

Fearnley-Whittingstall also provides a guide to boiling whelks, which will come in handy as soon as I finish describing it. As a prelude to the process of boiling, I should note an aside of Fearnley-Whittingstall that is helpful on the one hand and unhelpful on the other. At various points in their preparation, for instance upon removal from their shells or at the beginning of their boil, whelks may “release a certain amount of slime--don’t worry about this, just rinse it away.” (Fish 209 and again 329; apparently the observation is important enough to repeat) This quite obviously is helpful in avoiding unpleasantness if not to my effort to give the neglected whelk its best public relations profile, but practicality must out so I have reiterated the disclosure.

But back to practicality itself: Fearnley-Whittingstall likes to simmer whelks as gently as possible over the lowest heat in seawater for 12-15 minutes. Use tapwater and table salt if you are landlocked or lazy.

Here is my contribution to the campaign: Chinese style whelk salad, it’s simple and brilliant!

-Finely slice some boiled (or, more properly, simmered) whelks; you will need to have removed the coarse black cap and sludgy entrails first). Set the slices aside.

-Slice some spring onions (scallions to the Yanks) too;

-Slice some chillies (heat and quantity to taste);

-Peel and slice some fresh ginger;

-Make a vinaigrette of lime juice, vegetable oil, crushed garlic and white pepper

[Editor’s note: Apparently proportions are up to the reader. We go 2:1 on the ratio of lime juice to oil, and make about a quarter of the oil sesame and the rest neutral. The Raconteur likes his dressing oilier.].

Now combine everything in a pretty way and serve over lettuce, or nude on the plate.

The key innovation is the slicing of the whelks, which improves their texture; it also means that bigger as well as smaller whelks will do.

So goes the British vernacular, so go these ‘Chinese’ whelks; they go down a treat, and their flavour should go the distance in erasing memories of slime and sludge. If, by the way, this salad of mine does not sound particularly British, neither does China Chilo, and neither preparation is as likely to be found in China as in my house.

I had intended to experiment otherwise with whelks but have become distracted, and shall return to whelks once I have progressed with some catchy sloganeering for my campaign of relaunch and revival.