The Crawfish Problem in England

The crawfish problem in Britain is manifold. The introduction of a few American signal crawfish for commercial breeding during the 1970s not only failed to create a demand for crawfish products in Britain, but also wrought havoc among the native white clawed crawfish population. The signals escaped from their holding tanks and ponds, then proliferated in their new habitat.

The bigger, bolder and hardier signal crawfish are faster swimmers than the natives, can move on land and can survive for months out of water. Perhaps worse, signals carry a fungus that is harmless to them and fatal to the British natives. The signals also are less prone to disease in general, less sensitive to pollution and eat the natives or crowd them from their habitats. They are not different in kind from the white clawed species; rather, they are better at what both species do. The signals are so dominant that they threaten to extinguish the white clawed natives altogether.

Thoughtful observers including Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall and Mark Hix believe that the solution lies with consumption. Instead of allowing people to trap and eat what have become pests, however, the British government requires a permit process that is so arduous, and places so many preconditions and restrictions on trapping, that it is virtually impossible legally to catch crawfish. Permits are required from multiple agencies, permission must be obtained from landowners adjacent to the stream, live crawfish may not be transported so the catch must be consumed locally and it may not be sold unless the trapper adds to this battery of permits.

In response to the problem, Fearnley-Whittingstall for one advocates illicitly trapping and eating signal crawfish: “This is the kind of civil disobedience we feel entitled to recommend!” (Fearnley-Whittingstall 548).

In an effort to help save the British crawfish, our Rural Correspondent has rallied to the call and poaches signals from the Thames and its tributaries in Oxfordshire. He has purchased a trap--it is a wire cage that resembles a pocket lobster pot--and gives them away as presents to promote white clawed conservation.

The Rural Correspondent has found that a small carcass of pigeon, rabbit or squirrel is the best bait (Fearnley-Whittingstall recommends a can of cat food punctured with an awl; Florence White advised her readers to try liver). He therefore scours the back roads outside of Oxford for roadkill in his MG. Dressed meat does not work as well; the first crawfish into the trap devour it before their rivals can join the feast, so only a few of them enter the trap.

With roadkill the trap fills to capacity because, understandably enough, the crawfish find it more difficult to claw through the mangled carcass and tear at the meat, so more of them get the opportunity to meet their doom. The key to trapping signal crawfish is getting the trap out of the water in time. With overcrowding they become even more than normally aggressive and when the roadkill runs out they resort eagerly to cannibalism.

The crawfish season in the English Midlands varies but does run a little later than the season in the warmer climate of Louisiana, from sometime in May into October. During the good months, our Rural Correspondent catches so many signals that he cooks them, dresses them and freezes the peeled tails by the gallon bag. Unlike their little cousins, there are so many signal crawfish in the Thames that they face no threat of demographic as opposed to individual annihilation.

Another problem associated with crawfish in Britain is the unavailability of legal redress for damages to the trapper given the underground nature of trapping. One day, as the Rural Correspondent ambled to the riverbank to inspect his trap, he spotted two figures absconding with it at speed. There was nothing to be done. Given the low cost of traps (about £15) and the high seasonal yield, however, this kind of misfortune may be considered acceptable economic overhead, much like retail shrinkage of inventory that results from shoplifting or employee theft.

At this writing, not many patriots have followed the lead of our Rural Correspondent and engaged in principled civil disobedience to save the British crawfish. That may be because few people in Britain think about eating crawfish of any kind, and indeed the few British restaurants that seldom offer them usually do so only as the occasional garnish or random curiosity. That is strange because crawfish are cheaper (or free if you know our Rural Correspondent: As noted, he generously gives his considerable surplus away) and taste better than lobster, shrimp or langoustine. The problem is finding crawfish for sale anyplace other than Billingsgate.

We suspect that this is because nobody in Britain knows what to do with them: The Rural Correspondent is an exception only because he has persuaded one of the more skilled crawfish cooks in America (the Editor) to teach him how to prepare them. Most traditional British cookbooks ignore the crawfish altogether (but Florence White does give them almost a page in Good Things in England: She recommends adding cooked tails to green salad or heating them in ‘Foundation White Sauce’). (White 141-42) Neither Elisabeth Ayrton nor Elizabeth David or Jane Grigson offers a recipe and even the energetic and subversive Fearnley-Whittingstall only provides instruction for boiling them in plain seawater (no seasonings; a horrifying prospect to Louisiana aficionados of the crawfish boil). He does not include any actual recipe in his 607 page River Cottage Fish Book and neither does Lindsey Bareham in The Fish Store. As MacDonald Hastings and Carole Walsh note of Britain in Wheeler’s Fish Cookery Book, “[f]reshwater crayfish [sic], which are common in all our waters, are, surprisingly largely ignored in this country.” They recommend baiting a net with “any over-ripe [sic] fish or meat available” and boiling the catch right on the riverbank. (Hastings 111)

Britain is not the only country with a cuisine that neglects crawfish. In fact there is a dearth of crawfish dishes in every significant regional cuisine outside of Louisiana despite the ready availability of the foodstuff in the wild. Like Fearnley-Whittingstall, most cooks who do think of crawfish simply boil them whole in salted water (Swedes add lemon and dill) for peeling and eating in the rough. Regional Chinese recipes exist (Cantonese ones seem best) but in a country where people will eat just about anything (and good for them too), it seems strange that there are so few crawfish preparations.

Like their British rivals, the French seldom use crawfish other than as an occasional afterthought to sauce finfish or veal. The exception, however, is Alsace, where a handful of good traditional recipes exists. These include a flan, a rich ragout, a sort of ettouffe in Sylvaner, a creamy chicken and crawfish stew with Riesling, and crawfish poached in Gewurztraminer. (Gaertner and Frederick 122-25, 166-67)

Of course, Louisiana cooks revere the crawfish. They steam them with corn and potatoes in a broth flavored with crab boil, a mixture that resembles European pickling spice laced with a jolt of chilies. They cook them in Sauce Creole and in famous preparations like gumbo and jambalaya. Louisiana cooks make crawfish ettouffes and fricassees, sautés and salads, soups, bisques and gumbos, pies both baked and fried, sauces for fish, veal and pork, and even in a variation of carpetbag steak. Again, however, they are a global anomaly.

At Bayona in New Orleans, chef and owner Susan Spicer curries crawfish tails in addition to preparing a run of imaginative Louisiana dishes. One would think the British might catch on: They curry everything else, including shrimp, and in fact crawfish make a sprightly alternative for use in most recipes incorporating shrimp or even scallops.

There are glimmers of change. Barack Obama was elected President of the United States and, back in Britain, Mark Hix started what he hopes to make an annual public crawfish feast in London last year: We wish the project well. Hix also includes a pair of crawfish recipes in his new book, British Seasonal Food. One, potted crawfish, is simple, original, logical and brilliant: Potted shrimp is a classic of British cuisine, so why not potted crawfish too? It results in a brighter, milder version than the shrimp.

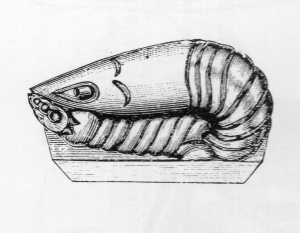

Hix calls the other recipe “rabbit and crawfish stargazy pie” which, however, it is not. Stargazy pie is an old Cornish preparation in which herrings or pilchards are placed vertically around the perimeter of a flaky shortcrust in a filling of bacon, cider and hardcooked eggs so that the heads of the fish protrude from the lid of the pie. Instead, Hix bathes his rabbit chunks and crawfish tails in a different filling, similar to the Alsatian stew, of cream, white wine and tarragon (we prefer thyme and note that chicken may be substituted for the rabbit, which is not only harder to find and more expensive in the United States than in Britain but also is unlikely to be eaten by bunny-loving Americans who do not tend to perceive rabbits as pests). No clump of dead fish stares balefully out of Hix’s pie either, which, technically speaking, is not a pie at all; he does not line the pan with crust but instead simply tops his filling with a lid of fluffy suet pastry to make what the Irish call a ciste (apparently from the Gaelic for case or coffin). He garnishes it with a single demure “stargazy” crawfish carapace that is not nearly as alarming as a circle of scorched and rampant fish.

It is a well conceived recipe in the context of species management:

“Like everyone else, I’m keen to do my bit for the environment and sustainability was the thinking behind this pie. Rabbits and crayfish [sic]

are doing their fair share to ruin crops and destroy other water life [sic again pace rabbits and ‘water life’], so it makes sense to eat more of them to keep them under control.” (Hix 97)

Hix should have called his creation ecological ciste, to avoid confusion and attract the greenies. He also should ditch the insipid ‘crayfish’ usage.

So far so good, but a pair of recipes (one a starter) does not make a revolution. We therefore encourage our readers to submit crawfish recipes. They may originate from historical cookbooks or manuscripts that we have overlooked, or may be readers’ own original recipes that incorporate traditional British ingredients, seasonings and techniques. People who send us recipes may or may not receive a glamorous britishfoodinamerica T-shirt in return.

Meanwhile britishfoodinamerica is magnanimous enough to give the British public guidance in where to find instruction in the preparation of crawfish. As a stopgap, do something seldom done in Britain and prepare competently some authentic Louisiana food, and do it with the neglected but threatening signal crawfish; whether or not people can summon anthropomorphic affection for the white clawed crawfish as they do for pandas and polar bears, nobody wants to witness the extinction of another species.

For the few British cooks familiar with farmed crawfish tails, the first encounter with wild signals can be somewhat alarming. Unlike commercial crawfish, they vary considerably in size; some become nearly as large as New England lobsters. When cooked, wild signal tails range in size from the circumference of a nickel or five pence coin like the Louisiana variety; to the size of quarters or pound coins like Chinese crawfish; and some to the diameter of clay pigeons. Just use common sense and cut the smaller tails into uniform pieces as needed, or treat the big ones like the lobsters they resemble. The claws are good to eat, so the big ones are worth cracking.

A number of Louisiana authors include accessible crawfish recipes in their cookbooks. Among them are Rima and Richard Collin, John Folse (who, incidentally, makes a case for significant British influence on the development of Louisiana foodways), the overexposed Emeril Lagasse, the underappreciated Paul Prudhomme, the wonderful Susan Spicer and the more obscure Terry Thompson. The recently reissued compilation of New Orleans recipes published by the local power utility, Entergy, called Cooking with Entergy, is another source among many. For the parsimonious, internet recipes are available but beware their frequent unreliability.

A recipe for britishfoodinamerica’s own simple ettouffe appears in this number of the practical.

Sources.

Anon., Cooking with Entergy (New Orleans 1997)

Author’s interviews with britishfoodinamerica’s Rural Correspondent (April 2007- December 2008)

Lindsey Bareham, The Fish Store (London 2006)

Rima and Richard Collin, The New Orleans Cookbook (New York 1975)

Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, The River Cottage Fish Book (London 2007)

John Folse, The Encyclopedia of Cajun and Creole Cuisine (Gonzales, LA, 2004)

Pierre Gaertner & Robert Frederick, The Cuisine of Alsace (Woodbury, NY 1981)

MacDonald Hastings & Carole Walsh, Wheeler’s Fish Cookery Book, (London 1974)

Mark Hix, British Seasonal Food (London 2008)

Emeril Lagasse, Louisiana Real and Rustic (New York 1996)

Paul Prudhomme, Chef Paul Prudhomme’s Louisiana Kitchen (New York 1984)

Susan Spicer, Crescent City Cooking (New York 2007)

Terry Thompson, Cajun-Creole Cooking (Tucson 1986)

Florence White, Good Things in England (London 1932; reprinted 2003)