Our American Correspondent in Egypt Meets the British in Cairo

The British abroad, in this case in Cairo: A World Cup draw and the preservation of identity, with our Egyptian Correspondent’s musings on African beer.

As an American in Cairo, I’ve managed to crash the Ace Club, an expat hangout in the suburbanesque area of Maadi. Expats favor the neighborhood for its remove from the noisy, chaotic heart of Cairo, and along its treelined streets you also will find the expansive and often beautiful houses of uppercrust Egypt.

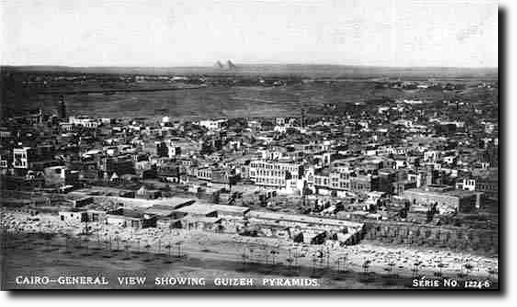

Edwardian Cairo

For admission to the Ace you require either an invitation from a current member or the payment of twenty pounds (with appropriate passport) for a pass that identifies you as a “potential member.” I had heard about the place from my American roommate, a graduate student from Louisiana who missed the comforts of his lifestyle at home, specifically bacon, and therefore had developed designs on the club’s kitchen. We decided to go during the World Cup, and not just on any night: It was England against America and we hoped both to cheer for our country and reach an embarrassing level of intoxication.

We paid at the gate and got in. Before describing the club and its inhabitants, I should mention that actual Egyptians of my acquaintance were utterly unaware of its location, let alone existence. The Ace is to Egyptian culture as General Tso’s chicken is to Chinese food. It is fanciful, fabricated and westernized. The entire staff was South African, but nobody appeared to find it remarkable that the whole workforce was imported along with everything else. The entrance was a sort of “Stroller Park,” a miniature playground of abandoned MacLarens and noisy kids. The Ace is a ‘lifestyle club’ where expat families can go together; the kids romp in a gated yard of swings and slides while the adults swig drinks and sample dainties under an outdoor tent.

The tent itself is impressive: It spans a tiled courtyard of tables and chairs. The fabric is patterned with Bedouin arabesques, and the only deviation from the Arabian Nights was the projector that allowed us coverage of the game. The fans who had gathered to watch turned out to hold more interest than the game itself. I do not know where in Cairo to procure a fright wig stained with St. George’s cross or a top hat colored in ‘union jack’ but the Ace had found plenty of both.

Beers priced cheaply starting at 9 pounds Egyptian fuelled a pregame frenzy. At least outside of the Ace, beer is not widely available in Egypt. Beer brands there are not numerous: I saw four at most, including a non-alcoholic imposter. Egyptians become confused when I tell them that, in the States, few people drink the nonalcoholic ‘malt beverages’ ubiquitous here. When it comes to real beer, with real alcohol, imports are available (for a significant price), but I would recommend Sakara, named for the stepped pyramid in the desert outside of the city. It has less alcohol than Stella, the other common beer, but its taste is superior and the brew is less likely to leave you with a pressurized skull in the morning. A key to drinking in hot hot Cairo is preemptive hydration; you sweat to death in bed, so buy insurance in the form of (bottled) water or you will run to the john (with the runs) and establish a pharoahic hangover. Counter to the intuition that should encumber this advice, ask for the bartender to give you a tumbler and a double when drinking the hard stuff; the price seems not to vary by volume, so you get your money’s worth from each ten pound shot.

When you do find some beer in a restaurant or bar, the markup runs to an order of magnitude over the 6 pound price at the liquor store: The beers at the Ace, at only 3 pounds over retail, therefore kept on coming over the bar. The British had been drinking for quite some while. These neo-colonials were here for the same reason as most of the American excolonials we met: Oil. The bet is sound that when you meet expats below the age of twenty-seven in Cairo, they are here to study language or politics; go above the twenty-something divider and they usually are traversing the Middle East brokering petrodeals.

When you do find some beer in a restaurant or bar, the markup runs to an order of magnitude over the 6 pound price at the liquor store: The beers at the Ace, at only 3 pounds over retail, therefore kept on coming over the bar. The British had been drinking for quite some while. These neo-colonials were here for the same reason as most of the American excolonials we met: Oil. The bet is sound that when you meet expats below the age of twenty-seven in Cairo, they are here to study language or politics; go above the twenty-something divider and they usually are traversing the Middle East brokering petrodeals.

The sunburnt potbellies at the bar were friendly enough, pleased to chat with a Yank or two. They promised our sound defeat on the pitch; we traded friendly jibes over the BP spill in the gulf, Bush the Younger and the Revolution.

The soccer progressed and the mood changed. The England supporters switched from predictions of victory to explanations of why they should have won. All those libations coupled with a territorial obsession as the founders of ‘football’ soured the mood: “You Yanks don’t deserve to tie us” had become the standard refrain. I wasn’t exactly lucid at that point, but was sufficiently diplomatic to remind my hosts that the competence of the States’ side simply reflected America’s global dominance. Smooth of me I know.

When it comes to British culture at the Ace, some things stand out. The mood was British, to the point that it is possible to pretend you never left the archipelago: You are drinking in a pub located in the Home Counties but for the heat and tent outside. The English in particular among the British abroad possess a quality that glues them together, an ability to find a place in defiance of locale and make it their own. This imperial holdover allows them to preserve their national culture and pride against all comers. Football, as noted, is ‘their’ sport, and the fact that the Americans tied their team became a hormonal challenge. Even their negative stereotypes, even binge drinking, become something English and therefore worthy of exaltation. Round after round with my older British companions acquired a pattern early on: Each of us bought one in turn, insulted each other in turn, and repeated the cycle until someone knocked something over and we became, however temporarily, distracted. If you want to bond with an expat and boast a strong constitution, buy the first round, but be prepared to let the rest of the circle treat you in turn.

I enjoyed my time with the British at the Ace. It is nice to speak with someone in your native language while abroad and I was fascinated by the anthropology of vestigial behavior from the imperial project. The British penchant for adaptation without assimilation has survived the end of empire, for better and worse, along with the ability to export a robust if raucous and raw way of life. The exception, in Cairo, was their food, which was nowhere in evidence, at least as I understand the attributes of British cuisine from my discussions with the Editor. The Ace served generic “continental” cuisine live from the 1950s but that, in its way, was thoroughly British too.