Art & Appetite: American Painting, Culture, & Cuisine at the Art Institute of Chicago.

“Art and Appetite” may be the first effort to take a scholarly approach to the depiction of food by American artists. That alone should make the exhibition important, but it has received virtually no notice outside Chicago, a fact that speaks volumes about the neglect of the north coast by culture vultures to the east and west. Their silence is all the more galling because the Art Institute has mounted a stunning multidisciplinary meditation on American culture--artistic, economic, political and technological--imagined through the prism of what we eat.

Chicago represents a more than appropriate site for this pathbreaking endeavor which, according to the School of the Art Institute student blog, has been eight years in the making. For decades the city not only functioned as Sandburg’s hog butcher to the world, but also as the source of endless innovations in packing, preservation and transport. Chicago is, to use William Cronon’s term, nature’s metropolis, the great city on the doorstep of the agricultural plains and nexus through which the essential railroads carry all manner of food east, south and west.

The show begins predictably and brilliantly with Thanksgiving before going chronological. A single painting hangs on each wall of the entry vestibule that leads to the broader explication of American foodways.

Those first four paintings in turn reflect attitudes celebratory, disdainful, conflicted and playful. There is of course the wartime reverence of Norman Rockwell; whatever his deficiencies, they are oddly welcome here. Lichtenstein characteristically commodifies a turkey to render it ugly and alien; Alice Neel portrays the poor bird (in fact a capon) as something like a humiliated homicide victim.

Doris Lee, Thanksgiving c. 1935

Then there is Doris Lee, who painted the least familiar and most interesting picture of the four in 1935. The figures she has rendered resemble plump American incarnations of L. S. Lowry’s lonely city folk from the north of England with some striking differences. He places all his men and women outside; all of Lee’s indoor people are women or children and unlike Lowry’s haunted urban landscapes no anomie lurks in their rural kitchen.

As Judith Barter explains in the superb exhibition catalog, Lee’s painting portrays “plain farm people, wearing unfashionable housedresses, laboring in a room of old linoleum and plain furniture, with screaming children and barely controlled chaos.” (Art and Appetite 41) Every adult appears industrious, not a one unhappy in the least. It is the image of an America already disappearing in 1935, “of ordinary people and farm life;” to self-styled Chicago sophisticates this “depiction of Thanksgiving as a rustic social gathering seemed boorishly common.” (Art and Appetite 41)

Josephine Hancock Logan, socialite trustee of the Art Institute, loathed it. The ‘atrocious trash’ represented an example of radical modernist “aberrations” at their worst. A museum should inspire and uplift; dowdy drudges debased its mission and had no place within its walls. It is more than mysterious why Logan hated the picture, and what she proposed instead; perhaps a classical motif with reclining Romans in togas nibbling turkey legs might have sent a more acceptable message.

Boorishly common the picture may have been, but also more than a historical trope; it embodies what the holiday still should be, not least in the city and, for the luckier among us, what the feast remains. That is why the public loved the picture and so, apparently, did the Art Institute itself. The museum not only purchased the painting but, with an exquisite eye for irony, granted it the annual Logan Medal; in response our friend its namesake founded “Sanity in Art” to try and excise the work and similar junk from all such institutions.

The promotion of Lee’s lovely but lost minor masterpiece to bat leadoff is a bravura curatorial performance. It embodies the theme of the show itself on any number of levels, from the ineffably American setting, its taut combination of romance and realism, not least to the disparate responses it engendered. Levels of irony inform the selection as well, within the painting and also in its association with the city of Chicago and the Art Institute, including of course the poke at Mrs. Logan and her affronted but ineffective poke back.

Change, throughout the time and space covered in the exhibition, remains a constant, even within Lee’s bucolic scene, in the form of an intruder wearing fashionable fur, a woman who doffs her florid and equally fashionable hat; someone, perhaps, like Mrs. Logan. In her way she embodies the advent of an unintentional twist on urbs in horto.

The chronology kicks off with unexpectedly strong Federal still lifes from Raphaelle Peale. They are good enough to stand alone but the Art Institute has given us more in the guise of historical context both written and wrought. The commentary posted by each painting or print provides considerably more detail than the conventional exhibition tends to do, and the information is welcome. We learn that all those still lifes did not merely look back to Old Masters but rather reflect an Enlightenment ideology of relentless improvement. It applied equally to political philosophy, technology and horticulture.

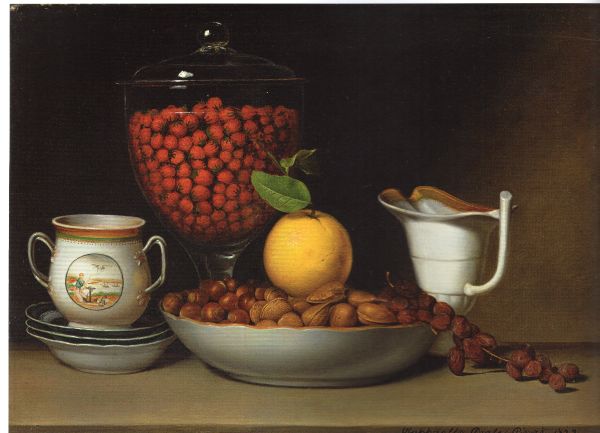

Raphaelle Peale, Still Life-Strawberries, Nuts, &c., 1822

Farming was big business, then as now (incidentally Archer Daniels Midland is a sponsor of the show), but considered more benign. The introduction of crops, extension of arable land and expansion of yields fascinated farmers from the freeholds of New England throughout the midAtlantic and even all the way down to the slaveholders of the low country south, as Joyce Chaplin has demonstrated in An Anxious Pursuit: Agricultural Innovation in the American South, 1730-1815.

As a result Peale gives us much to see provided we are willing to look. A single example out of his still lifes, “Still Life--Strawberries, Nuts &c.” painted for a Philadelphia patron in 1822 (squarely within Chaplin’s innovative era) alludes to neoclassical aesthetics; the taming of nature; the ‘forcing’ of fruit in greenhouses for harvest out of season; manufactures, trade and the attendant prosperity of the fledgling republic; regional tensions between north and south; and more, all of it explicated by the text beside the picture. A case adjacent to ‘Strawberries’ holds the actual jug (ca. 1790, from China, depicting a prosperous port of Philadelphia) and urn (of glass and holding the berries; an allusion to greenhouse-based botanical experiments) that appear in Peale’s painting.

Other artifacts accompanying the visual art include gardening manuals, cocktail equipment and cookbooks. There are the essential publications of, among others, Amelia Simmons, Mary Randolph and Sarah Rutledge, Sarah Josepha Hale and Francis Merritt Farmer along with nearly unknown items like Mrs. Gardiner’s Receipts from 1763, the facsimile of a manuscript published privately in Maine during 1935.

Other artifacts accompanying the visual art include gardening manuals, cocktail equipment and cookbooks. There are the essential publications of, among others, Amelia Simmons, Mary Randolph and Sarah Rutledge, Sarah Josepha Hale and Francis Merritt Farmer along with nearly unknown items like Mrs. Gardiner’s Receipts from 1763, the facsimile of a manuscript published privately in Maine during 1935.

The show also slides ephemera into the mix, including advertisements, promotional pamphlets and posters. The one of a “porcinograph” or “gehography” that shapes the United States as a pig (Cuba has become a sausage and the Hawaiian Islands are hocks) and reproduces the coat of arms for every state, the date of its foundation and its ‘representative’ foods. “Clambakes, Pork, Chowder and Egg Nog” represent Rhode Island; gumbo, an apocryphal ‘poussoneau’ and larded beef (!) supposedly embody Louisiana (had the Massachusetts creator of the hogography ever been there?).

As the exhibition explains, the hogography appeared in 1875 to celebrate the centennial of Bunker Hill as well as the completion six years earlier of the transcontinental railway, linking the United States to create a unitary market in agricultural commodities--like pork. Hardly high art, it is one of the most evocative and uniquely American images in the exhibition and perhaps the Editor’s favorite.

Coverage of the nineteenth century more generally is, like treatment of the eighteenth, strong. The curators have made the exemplary choice to describe the various American foodways as well as their evolving depictions, so, for instance, we get not only stunning plates and silver cups designed for the service of oysters, but also pictures of oyster houses and a good description of the considerable culture that developed in connection with their consumption.

The coverage continues apace. The Victorian cult of refinement; the gluttony of the gilded age with its concomitant vogue for trompe l’oeil paintings of kitchens, hearths and foods including carcasses in heaps (a fashion previously unfamiliar to the Editor); and the neocolonial reaction to excess in foodways as well as art, architecture and design each gets more than its due.

It would be a shame to end an otherwise glowing review on a low note, so the caveats appear here. While it is beyond debate that women dominated cooking and, in Anglophone cultures, the literature of cooking at least until a decade into the twentieth century, the recurring reference to gender and gender roles at “Art and Appetite” is tiresome if inevitable; the obsession is an inescapable parlance of our times, and historiography along with anything else reflects its era. Then again, the explication of midnineteenth century picnic paintings that discusses the freedom from rigid morality and conventional sex roles that outdoor dining gave the middling classes is both welcome and convincing.

The gallery devoted to late twentieth century art, in contrast all the others, appears an afterthought. More art, and any artifacts, should have been included to cover the period. A striking omission, for example, is anything produced by the fluxus movement; no wedge of pie sculpted from chrome by Robert Watts or voluptuous calliope fashioned from candy wrappers (‘lick me’) by Al Hansen, no “Literature Sausage” by Dieter Roth.

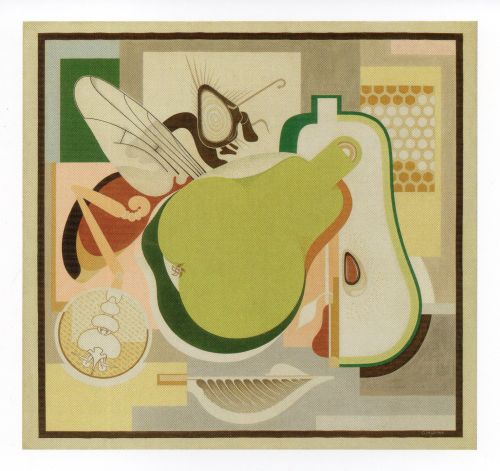

The curators also missed an opportunity to provide the show with a symmetrical flourish. One still life in the exhibition, Raphaelle Peale’s “Covered Peaches” from 1819, includes a bruised peach and a wasp sucking juice from the fruit, an allegory of aging, decay and death. The Dutch painted this kind of memento mori as early as the seventeenth century, as the show’s catalog notes. In 1929, Gerald Murphy returned to the theme with “Wasp and Pear,” a creepy and beautiful painting that would have made an apt addition to the exhibition.

The curators also missed an opportunity to provide the show with a symmetrical flourish. One still life in the exhibition, Raphaelle Peale’s “Covered Peaches” from 1819, includes a bruised peach and a wasp sucking juice from the fruit, an allegory of aging, decay and death. The Dutch painted this kind of memento mori as early as the seventeenth century, as the show’s catalog notes. In 1929, Gerald Murphy returned to the theme with “Wasp and Pear,” a creepy and beautiful painting that would have made an apt addition to the exhibition.

In the end, however, none of these criticisms detract much from the impressive impact of “Art and Appetite” and with any luck the show will serve as the precursor of similar explorations.

From the particular perspective of britishfoodinamerica, the show makes an implicit and trenchant point. Without saying so, the recipes and artifacts on display and in the catalog confirm the persistence of British foodways throughout nineteenth century America. One of the wall blurbs at the Art Institute points out that “[b]eginning in the late 1880s, Americans became curious about French cookery….”, a date considerably later than their British counterparts. Before then, we find a preponderance of British influence on the American kitchen in dishes from potted pigeon or boiled turkey with oyster sauce to greengage preserves.

Nor did the British influence disappear altogether with the new century. The bill of fare for the 1922 “Yule Feast” at the Lotos Club in New York, one of the menus displayed in the exhibition, features turtle soup, “English Baron of Beef,” Yorkshire pudding, “English Plum Pudding” and Devonshire cheese.

The Art Institute has commissioned a number of chefs to create their own interpretations of traditional American dishes in conjunction with the exhibition, including Eric Mansavage from the wonderful Farmhouse bar and restaurant on Chicago Avenue hard by the Franklin Street El. While he sources all his food and most of the drink from the Midwestern states of Illinois and its immediate neighbors, Mansavage has chosen those British paradigms, a fruitcake and custard.

Wall mural, Farmhouse restaurant, Chicago

Not, of course, that British food is the focus of “Art and Appetite.” And yet, for much of the long period that it reviews, the exhibition is in its way an exploration of British food as it has flourished and evolved in America.

“Art and Appetite” closes on 27 January before moving on to Fort Worth.