Offcuts & outliers, Part I: A sort of rant involving the decline of culinary standards with some modest suggestions for addressing the problem, including notes on offal, pie birds, Queen Victoria and hot girlie action.

Instead of working in the kitchen, many of the braying charlatans who have displaced competent cooks on the Food Network travel about the United States attempting to titillate their viewers by trumpeting what they label strange. Not the Editor; she hesitates to label any foodstuff or dish bizarre. If something can be grown it should be eaten, and if we are going to kill animals for food then we ought to consume the whole beastie, not only out of a certain respect but also to kill fewer of them.

Andrew Zimmern from Bizarre Foods

The Editor is no acolyte of M. F. K. Fisher but on this point she shines:

“If we are going to live on other inhabitants of this world we must not bind ourselves with illogical prejudices, but savor to the fullest the beasts we have killed. Why is it worse, in the end, to see an animal’s head cooked and prepared for our pleasure than a thigh or a tail or a rib?” (quoted at McLagan 15)

Not many people in the United States adhere to that perspective. Culinary elitists fete April Bloomfield and Fergus Henderson for their ‘nose to tail’ ethos, and we hear a good deal about sustainability, but nobody means any of it. Americans eat far too much and yet not only waste a large proportion of food but also consume too little of it in terms of variety.

It was not always so. A quarter of the recipes for meat in the 1908 and 1909 issues of Good Housekeeping used mutton, rabbit or offal of various kinds; during 1968 and 1969 the proportion had declined to less than three percent. The upshot is predictable. A 1978 poll of teenagers by Scholastic Magazine found that their favorite foods were burgers, pizza and steak; now that they are the people who do the ‘cooking’ the trend toward a narrowing range of ingredients, and to prepared foods, has accelerated. (Schwabe 407, 408)

Things have gotten so bad that unless you live in a Chinese, Hispanic or Portuguese community, or have access to their shops, you cannot find a kidney let alone the head of a calf, pig or sheep. Who carries caul fat? Even the cheap and versatile chicken liver, which may be fried to something near perfection in a net of caul, has become thin on the ground, or at least in the supermarket. Perhaps if we loiter by the dogfood factory they might throw us some of these scraps.

Thanks to the ludicrous inspection requirements of the Food and Drug Administration, nobody in the United States can get feathered game without the acquaintance of a hunter. In Britain you may take your pick of grouse, partridge, snipe, woodcock and more during the appropriate season; not in America, not any time at all.

Local worthies are not much better than the Feds. A single example of disutility; the city inspectorate in Providence, Rhode Island, thoughtfully shut down Farmstead, a shop with a following as far afield as San Francisco, the week before last Christmas. Their sin was storing cheese in an assiduously controlled room built precisely for the purpose because it was insufficiently cold to destroy any nuance of flavor.

Nor did the heirs of Buddy Cianci and other corrupt politicians past appreciate Farmstead’s cottage industry. Their production of peerless charcuterie was halted for reasons even murkier than the cheese embargo. Perhaps the nice proprietors of Farmstead did not know whom they should have paid off; spoiler for the libel lawyers, this last is meant in (just possibly) jest. Whatever its cause, this kind of thing blights the economic landscape at a time when politicians across every band of the mendacity spectrum bleat about helping small business.

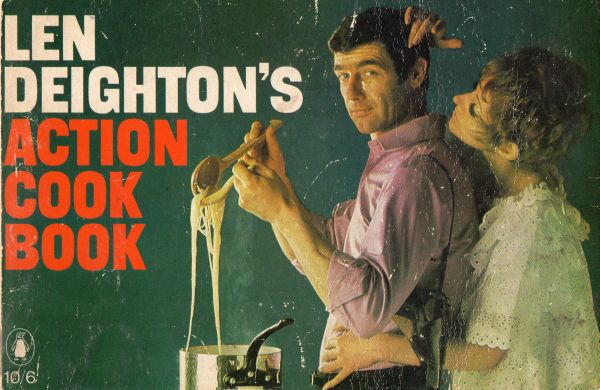

It all is part of our culinary world turned upside down, an era when farmers’ markets proliferate while the hawking of processed junk has created an underclass of diabetics. Len Deighton would encounter a mammoth obstacle to the publication of his acclaimed (and collectible) Action Cook Book a half century on, for passivity reigns. At a time when culinary programming draws record television ratings, and cookbooks comprise a lonely sector of health in the gutted publishing industry, fewer people than ever as a proportion of western populations actually cook.

It does not require a survivalist to wonder whether this inability to do something so basic creates a kind of primal void, a sense that something elemental is absent from our lives. We need not be self-sufficient in all things but ought to be able to nourish ourselves at least some of the time.

We are voyeurs instead of actors now. Tapping this trend, reality programming has expanded into contests to become the next network food star; the flamboyant attempts of celebrities to renew struggling restaurants; and the machinations of security operatives who install hidden cameras to catch employees berating customers, stealing from the till or giving away too many drinks.

These observations do not apply to everyone, especially not the readers of britishfoodinamerica. The site is too rigorous for the superficial to contemplate, and unfortunately too difficult to find for the accidental tourist. What is to be done?

Our recourse, of course, is cooking, and we might as well cook what the thoughtless call the weirdest possible things. Any number of publications past and present might speed us on this way.

Deighton himself is not the worst place to begin. Best known for his cold war spycraft (Funeral in Berlin, The Ipcress File) and a remarkably good treatment of the Battle of Britain, Deighton turned to the kitchen for a brief stint in 1965. He produced two culinary volumes, one on French food, which does not interest us, and his Action Cook Book, which does. From its cover we might assume that the action Deighton had in mind was sexual, but his Cook Book was a prescient endeavor in three ways.

First, the book contains “mostly English-style cooking” at a time when such was beneath contempt. (Deighton 6) It would require another decade for the great triumvirate of Elisabeth Ayrton, Elizabeth David and Jane Grigson most of all to usher along the revival of English foodways.

Second, Deighton realized that his audience probably could not cook (“I have assumed little or no knowledge on the part of my reader….”) (Deighton 6) and therefore includes some good conventional advice for the novice. He lists essential utensils, explains how and why to measure things, and outlines the perils as well as benefits of the refrigerator. This last item may sound timebound but, and this may surprise readers, Deighton’s points remain pertinent. Refrigerators do dry out food unless properly wrapped; refrigeration does not destroy bacteria; frozen fruit will lose its color if thawed too far in advance.

These warnings are basic but Deighton does not patronize and demonstrates some surprising finesse. For instance, at a time when nobody beyond the Indian subcontinent considered mustard oil, Deighton recommends the substance and explains how to use it.

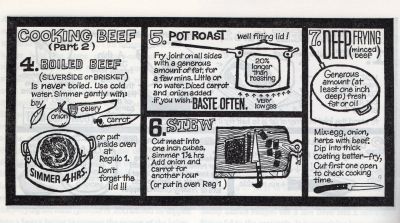

Third, Deighton’s “cookstrips” really set the book apart. He produced what could be called the precursor of the graphic novel, for the Action Cook Book presents a number of recipes as “cookstrips.” They are clean and playful cartoons that could have been inspired by the illustrations to Dorothy Hartley’s Food in England (it appeared a decade earlier) and demystify the assemblage of even elaborate dishes.

The strip called “Cooking Beef (Part 2)” exposes an important oxymoron: “Boiled beef (silverside or brisket) is never boiled” and goes on to explain, with admirable economy, how to boil beef. It must merely simmer slowly on the stove for four hours, unless you choose to stash it in a low low oven instead, but always upside down and “Don’t forget the lid!” (Deighton 92; boldface in original)

There is more to this than meets the eye. By identifying the two cuts, Deighton makes the tacit point that others, notably oxtail, shin and shank, require different treatment. The collagen in those cuts of the cow do require burping bubbles or it will not devolve into something silken.

For our immediate offbeat purposes, Deighton utilizes both butchers’ cuts and offal, which, he properly notes, “is the most neglected, cheapest and delicious selection of food on sale today” if, he might now add, there is any to be found. (Deighton 141) Chicken livers go into “Paté Minute, “a really fast party piece.” (Deighton 118)

Deighton draws recipes for brains, hearts, kidneys, oxtail, sweetbreads and tripe; surrounds a series of sausages made from scratch with caul; roasts a partridge and lots of other birds (even the elusive capercaillie, “perhaps our most delicious game bird”); and steams a classic steak and kidney pudding (“use same recipe for fruit pud.”). (Deighton 145, 146)

Who, as the song goes, could ask for anything more?

More may however be found in any number of places, including The Fifth Quarter: An Offal Cookbook from Anissa Helou. As her other titles would hint--she specializes in Mediterranean foodways--the focus of The Fifth Quarter hardly is British. Nonetheless recipes from the Isles both home and abroad do sneak into this work by a woman fluent in both Arabic and French. We could cook herring roes on toast along with braised oxtail from Arabella Boxer, roast bone marrow from Dorothy Hartley and cakes of the same from Ambrose Heath, Jamaican oxtail from Cristine Mackie, haggis (hurrah!) from F. Marion McNeill, and there is more. From this alone we like Helou, who is kind enough to identify her sources and has chosen them well.

Odd Bits by Jennifer McLagan, from her series that includes Bones and Fat, mines a similar vein but does not confine itself to offal. McLagen unaccountably finds bellies (bacon to us all, once smoked), jellies, lard pastry, shanks, short ribs and shoulder ‘odd,’ perhaps a reflection of the more squeamish and politically correct stratum of twenty-first century North America (she is Canadian). The overinclusiveness, however, does no harm, because readers will welcome recipes like the one for pork shoulder roasted slowly in cider with rhubarb.

Her clunky prose may be overconversational, her chapter headings overcute (e. g. “If I Only Had a Brain”) and her explanations overlabored (Is it really necessary to identify Victoria as “queen of England” in a discussion of marrowbone?) but her judgments, even extending to the pie birds beloved of the Editor, are sound. (McLagan 39, 189)

McLagan’s discussion of them embodies what is both good and bad about her books:

“I never see pie birds anymore, but they are very useful. It [sic; Editor’s note: Where is McLagan’s editor?] is a small china bird [Ed. again: or other animal or thing, whether representational or utilitarian, like an inverted funnel] with an open mouth that has a hole in it. You place it in the center of the pie and place the pastry over the top cutting a small slit in the pastry so the bird’s head can peak [sic; same note about an editor in absentia] out. It holds up the pastry and allows the steam to escape through its mouth.” (McLagan 87)

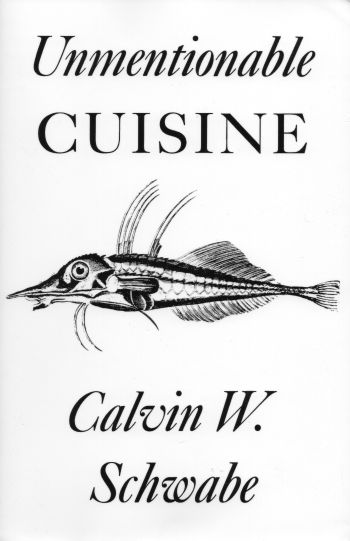

In defense of McLagan, she has chosen her manifold quotations well, from people both overexposed (Anthony Bourdain) and overlooked (the eccentric and estimable Calvin Schwabe, on four occasions). Besides, criticism may run in many directions, and the Editor is not immune; some may consider her own prose, at least in this review of Odd Bits, overparenthetical.

Schwabe can lay claim to a classic. His Unmentionable Cuisine is at once didactic, comprehensive and entertaining. Schwabe observes that “[b]ecause of prejudice or ignorance, we Americans now reject many readily available foods that are cheap, nutritious and good to eat.” (Schwabe 1)

Schwabe identifies the cause in no uncertain terms:

“The deterioration of the American diet can best be attributed… to a complex combination of affluence, laziness, and parental permissiveness, the biggest encourager of which probably has been a rapidly accelerating concentration of ownership and management in the food-producing, processing, and marketing industries…. This has led to aggressive promotion of the idea and the products of ‘agribusiness’…. ” (Schwabe 409)

That, he thinks, is a moral as well as culinary failing when much of the world goes hungry, so Unmentionable Cuisine “is meant to be a practical guide to help us and our children prepare for the not too distant day when the world’s growing food-population problem presses closer upon us and our overly restrictive eating habits become less tolerable.” (Schwabe 1)

This is all the more remarkable because the first edition of Unmentionable Cuisine appeared back in 1979, before the vogue for ‘nose to tail’ eating or the rise of concerns about sustainability.

Schwabe’s taste is nothing if not catholic; he will eat anything, from the udder of a cow to the head of a goose, a rat or a bat. He includes four recipes for sea urchin gonads. Ten pages cover insects of various kinds, including ants, beetles, crickets, and wasps, various larvae and pupae.

Neither dog nor cat escapes the knife. Schwabe discounts the possibility of “raising dogs or cats expressly for human food” but sees no reason why shelter dogs or cats should be destroyed, and a good one why they should be eaten. These abandoned animals would amount to

“at least 120 million pounds per year of potentially edible meat now being totally wasted. And even the disposal of this huge number of dog and cat carcasses poses an immense ecological and financial problem to the governments of many of our cities, some of them cities where some people cannot afford to eat much meat!” (Schwabe 167; emphasis in original)

Apparently the Chinese prefer puppy to dog, and housecats taste more like rabbit than chicken. (Schwabe 176, 177)

Schwabe includes sixty-five recipes he considers English, three Irish, two Scottish and two more Welsh (none of them for dog, cat, bug or balls, although he considers an English recipe for herring sperm in cream palatable). Schwabe, however, has undercounted by awarding a number of preparations to the wrong country. Corned beef, for example, was made and eaten all over Britain long before the advent of the United States. In a similar vein (although the book does not include recipes for veins), Unmentionable Cuisine has no British recipe for lamb kidneys, that staple of the Edwardian table and an ingredient still prized there today.

By now it should be apparent that recipes for haggis (“this classic dish of Scotland”) would have to appear, but Schwabe still pulls off a surprise by describing some nine of them, from ancient Rome, Algeria, Corsica (stuffed with an intriguing combination of spinach, beets, herbs and blood), Ireland (aptly enough made with pork and potatoes rather than sheep and oatmeal) and elsewhere. (Schwabe 138, 139)

One English variant, ‘Yrchins,’ gets its eccentric name from its appearance; a pork stomach stuffed with sausage is studded with slivered almonds and battered with egg, flour and blood to resemble a sea urchin or hedgehog. Another one fills a sheep stomach with breadcrumbs, sheep fat, seasonings and saffron. Its name, afromchemoyle, is at least as odd but considerably more mysterious. (Schwabe 104, 139)

If Schwabe can sound at times like a well-intentioned scold, the overall tone of Unmentionable Cuisine is playful. He confesses that to his mind the best thing about haggis is the large amount of whisky traditionally consumed with it. Elsewhere he explains that “if you feel very experimental and in a nostalgic mood,” serve his “small bits stew” from ancient times “as one course for a reconstructed Roman orgy.” (Schwabe 233)

Over thirty years after Schwabe’s book, Peter Ross made his own foray into the world of the strange with The Curious Cookbook: Viper Soup, Badger Ham, Stewed Sparrows & 100 More Historic Recipes. Ross has the resumé for the task; Principal Librarian at the encyclopedic Guildhall Library in London, he also oversees its collection of historical cookbooks. Like Schwabe, he enhances each recipe with narrative description, but Ross also adds their social background, other analytical commentary and the precise source for most of the recipes he quotes (for quote each source, again unlike Schwabe, he does).

And yet it is hard to place this book. Ross displays none of Schwabe’s earnest pleading, and does not appear to take his chosen recipes with much more than the odd grain of salt. Is he making fun of our forebears? He should be too serious an author for that. Does Ross advocate a return to some of these dishes with strange ingredients and stranger names? Maybe not; recipes are transcribed, and translated from archaic English, but not adapted to current practice.

Perhaps the exercise is but a trifle or lark (Ross includes recipes for both). It is not a scholarly text: This compilation comes with neither index nor bibliography. The slim volume (162 recipes) leans heavily on a handful or so of sources but ranges across more than five hundred years.

Ross himself offers little guidance. His introduction summarizes the development of cookbooks from medieval court manuscripts to publications with recipes designed to cope with the rationing and shortages of the Second World War--all in only twelve pages. He does nod toward the notion that the past is a foreign country, and justifiably reminds readers that cultural relativism is real; “one culture might consume dog with gusto and without sentimentality and yet feel physically sick at the thought of eating that rotting, mouldering lump of fermented cow’s milk known as blue cheese.” (Ross 1) Why not, like Schwabe, identify Chinese and Koreans as consumers of the dog?

In the end Curious Cuisine is a bit of a bathroom book. On those terms it is a bit of a gem. The Editor did not know, for instance, that the first recipe book printed in England, This is the Boke of Cokery, appeared only in 1500; The Forme of Cury, which dates to 1390 and often gets cited as earliest, was in fact a manuscript. Nor did she know that later additions of Mrs. Beeton included recipes for kangaroo soup and curry, roast wallaby and parakeet pie.

Then we have dishes of both compost and garbage. The original usage of ‘compost’ was for “a sauce or pickle of a type that the English have long savoured.” It sounds like an appealing variation on a chutney or Branston pickle; various vegetables, vinegar, lots of spice, honey and wine give it a classic sweet tart taste. (Ross 18-19)

‘Garbage,’ is a term common in America but not widespread today in Britain, where the preferred word for trash is rubbish. That makes a certain sense, for by its original usage garbage, if not a child of glamor, was far from useless. The original meaning of the term was “to take the best out of,” and that is what the cook would do by, for example, separating offal from muscle meat for use in differing dishes. Ross explains that became especially associated with parts of a fowl; the gizzard, heart and liver. They might contribute to some variation on Small Bits Stew. (Ross 19)

Perhaps Ross tries a little too hard. Any number of his recipes are simply not that weird although, to be fair, he includes one from Robert May for an incongruous combination of lips, noses, ox eyes and sparrows on toast. Ross cites Horse Artillery Pudding, Gun Troop Sauce and Beef Trifle as examples of recipes “given fanciful names to make them sound more attractive,” but it is hard to see how reference to the military would glamorize food. (Ross 146)

Most such names do in fact have their genesis at the point of reference. Over the years, however, the particular troop or regiment got lost as the recipe migrated from author to author, often without attribution.

Florence Petty, The Pudding Lady

The use of trifle is of course no military reference but rather a nod to what the word originally meant. This was something of little value, not something fanciful, fancy or even curious. The 1917 recipe from Florence Petty (whom we Appreciate) therefore is practical instead. It uses leftovers and frugal additions of egg, horseradish, margarine and onion; a handy enough recipe in wartime, especially for the working poor, who were Petty’s target readers, and listeners too. Petty was during the decades between the wars one of the most popular personalities to broadcast over the BBC, something else that Ross neglects to disclose. Her trifle tastes quite good, like an Ongar ham cake but made with whatever cold meat is to hand.

Then there is the mystery of lasagna, or, at least in fourteenth century England, ‘losyns’ or ‘lozenges.’ Ross interprets the recipe, from The Forme of Cury, as instructing the cook to dry thin sheets made with flour and water, boil them in broth, then layer them with cheese, spices and sugar. He notes that this “remarkably modern sounding dish [ ] is clearly the ancestor of our modern lasagna.” (Ross 14-15) Or is it? Does ‘lasagna’ mean ‘lozenge?’ Did the English invent it? Or is ‘losyns’ an outlier? The Curious Cookbook provides no clues. It is both incurious in one sense and not quite curious enough in the other sense of the term.

Making Medieval lasagna?

Genuinely curious, perhaps even strange and wonderful, recipes appear in the practical