A note about English spiced beef & the mystery of its American origins.

If britishfoodinamerica were a tabloid or magazine that traded in popular history we would entitle this essay something like “The True Story about the Lost Recipe of Britain.” That would be misleading. It is not as if anybody has lied about the nature of the dish or conspirators decided to bury it from public consciousness, but then most such pronouncements turn out to be distortions.

It is, however, hard not to wonder why spiced beef has disappeared. Spiced beef, like corned beef or pastrami, is a method of preserving meat that predates refrigeration. Butchers all over England used to spice beef, but no more. It is, however, cheap and easy to make, although it does require a week or so to cure, and you do have to spend five minutes or so with it for each day of that time.

The flavors are not archaic or extreme; they are spicy, sweet and salty, but also mild. And during this wintry season when we hunger for the comfort of family ritual, spiced beef would be a good one to revive.

The dish is associated by tradition with the holidays but may be cured and eaten, cold in thin slices, at any time of year. It keeps for a long time in the refrigerator and is handy for serving dinner guests or impromptu visitors during the busy season.

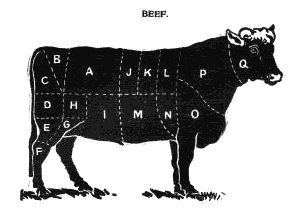

Suitable cuts of beef for spicing include brisket, chuck, top round, sirloin and shin. The cure that people use varies by temperament and region but the common denominator is the pairing of sugar and salt. Some cures add molasses or vinegar or both; juniper appears in spiced beef from some but not most parts of England. Black pepper goes into the cure a lot of the time and so does allspice in varying proportion. Henry Sarson added cloves, green herbs and, uniquely, rum in 1940. Old School cooks cook the cured meat under a blanket of fat to keep it moist.

Vincent Price, actor, art collector, philanthropist and devoted cook, also carried the torch for spiced beef. Come into the Kitchen, one of the cookbooks he wrote with his wife Mary, appeared in 1969. The inclusion of spiced beef in this American publication is very nearly astounding.

According to Elizabeth David, this 300 year old tradition had all but disappeared from Britain by the middle of the twentieth century, although Jane Grigson notes in 1974 that it survived in Ireland, particularly at Christmastime, and britishfoodinamerica has found an English recipe that remained in print at least until 1949. (Sarson)

Writing at some point in the 1960s, David claimed with typical self-promotion to have ‘rescued the dish from neglect’ by publishing her recipe in British Vogue during 1958; the master butcher at Harrod’s read the article and decided to pickle beef silverside (basically bottom round) for customers to cook at home during the Christmas season. (Salt, Spices 74-75, 263) It would have remained unknown, however, to all but the very few Harrod’s customers with the inside information that enabled them to order it--a miniscule proportion of the British population.

Before conducting our own initially theoretical research in 2009, spiced beef was unknown here at britishfoodinamerica; our informal polls indicate that it remains utterly mysterious in the United States as well as Britain and we have no American acquaintance who remembers the dish.

David notes that traditionally the cured beef was braised in a slow oven under cover of suet and sealed with inedible paste to keep it from drying but, writing sometime before 1970, she omits those steps and substitutes a seal of kitchen paper under a heavy lid. (Spices, Salt 174) Price, however, is one of those cooks steadfastly of the Old School:

“In a large covered baking dish place the suet with the meat on top of it. Pour on the water [a scant cup; authentic too]. Seal the casserole with a strip of dough.” (Kitchen 50)

His recipe reflects rigorous scholarship; other American cookbooks from the sixties do not include recipes for spiced beef, let alone authentic ones.

What was Price’s source? Come Into the Kitchen was chronicling American foodways, so the original imprint ought to have been American. It probably was; his recipe has another earmark of authenticity that initially appeared to us to be an oversight. British spiced beef recipes usually include juniper, but Price omits it from his cure. David observes that cooks outside of areas where the bushes grew wild, including Cumberland, Sussex, Wales and Yorkshire, also traditionally omitted juniper until her revival of the recipe:

“The presence of juniper berries among the pickling spices makes the recipe somewhat unusual.” (Spices, Salt 173)

If the attributes of Price’s recipe point to authenticity, they (and he) do not reveal its source. Neither the notations made between 1749 and 1799 that Karen Hess assembled as Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery nor Amelia Simmons’ American Cookery from 1796, widely if perhaps wrongly considered ‘the first American cookbook’ by Dover Publications and many others, includes a recipe for spiced beef. No such instructions appear in The Carolina Housewife by Sarah Rutledge (1847) or any other American cookbook we have found either.

To add juniper or not…

Instructions “To Dry Beef for Summer Use” and “To Corn Beef in Hot Weather” do appear in The Virginia House-Wife from 1824 (also called “[t]he first truly American cookbook” by Dover), but they omit spices altogether. We can rule out the recipe for cured beef from the 1839 Kentucky Housewife: It omits the berry too, but boils the beef immediately after salting and spicing rather than allowing it to steep in the mixture, which unlike Price’s includes “cloves, cinnamon and nutmegs and cayenne pepper” in addition to his allspice; also unlike Price, it adds molasses to the sugar and smokes rather than braises the meat--because the Kentucky version was meant for summer preservation rather than Christmas feasting. (Kentucky 30)

In Southern Food, John Egerton makes tantalizing reference to “an old Nashville cookbook” that includes a recipe for a dry cured “spiced round.”

As reproduced by Egerton, the recipe itself points to English antecedents. It uses a cure based on salt, brown sugar and saltpeter that is seasoned with allspice, cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg and black pepper. Like Price, Egerton also specifies cooking the cured meat with fat, in his case either suet or, in a departure from English practice, pork fat.

Unfortunately Egerton neither identifies his source nor includes anything from Nashville in his bibliography, so our attempt to find a route to the origin of spiced beef in America remains a dead end.

It did resurface, if for only a During December 2005, Claire Hopley included a recipe for “English Spiced Beef” in the “Get Wrapped holiday section of the Boston Globe. Hopley credits both Mrs. Grigson and savid for the recipe, which essentially is Mrs. Grigson’s with the addition of cinnamon.

We have found three recipes, two traditional but one decidedly modern, that reliably produce excellent spiced beef and they appear in the practical.