A note on cooking with beer, including reviews of Beer & Vittles by Elizabeth Craig & Beer & Skittles by Richard Boston.

At least until the recent craft beer revolution, beer meant something different in the United States than in Britain. In the United States it still tends to denote only lager or Pilsner and usually light rather than dark. To British ears, however, beer is a catchall for anything brewed with malt and hops, from lagers to all manner of ales, porters and stouts. So while Americans commonly refer to lagers and Pilsners as beer, Britons always request them by name. Ask for beer in a public house and you likely will either irritate the barman or get something at his whim.

At least until the recent craft beer revolution, beer meant something different in the United States than in Britain. In the United States it still tends to denote only lager or Pilsner and usually light rather than dark. To British ears, however, beer is a catchall for anything brewed with malt and hops, from lagers to all manner of ales, porters and stouts. So while Americans commonly refer to lagers and Pilsners as beer, Britons always request them by name. Ask for beer in a public house and you likely will either irritate the barman or get something at his whim.

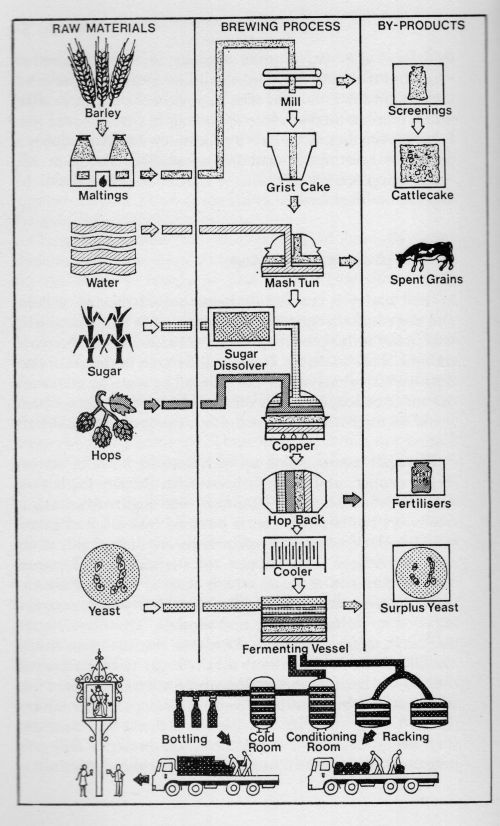

In both cultures, ale remains a specific descriptive for something top fermented (the yeast floats on the surface) rather than bottom fermented (the yeast is all submerged). Ales mature faster and taste of more tang but are harder to brew with any kind of consistency. Wild yeasts in the ambient air can combine with the brewer’s dose to alter the flavor of the beer, to some minds a happy bonus, to others a distressing threat to quality control.

Britain traditionally was an ale drinking nation, and although that is (regrettably) changing, it has followed the United States to support an increasing cadre of small craft brewers who work predominantly with top fermenting yeasts. The British style tends to differ from the American; beers are not so big. Alcohol levels tend to lie lower, both because traditional styles are milder (less hopped up too) than American innovations like the blockbuster double, triple and West Coast IPAs, and because British tax on beer rockets as its alcohol level rises.

A lot of lousy lager infests Britain, much of it foreign names brewed there under license. They tend to be bland mainstream lagers and many of them are even worse than their counterparts abroad because the licensees brew them with cheap adjuncts and lower levels of alcohol than in their places of origin. Only the names are the same.

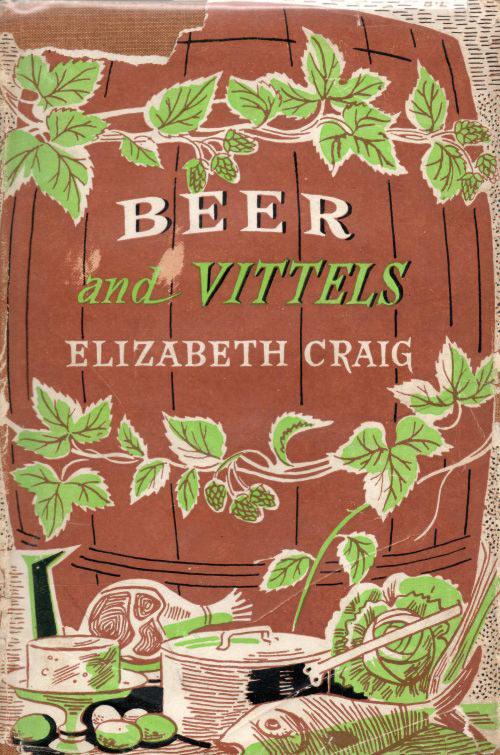

These musings got the Editor thinking once again about food, this time made with beer. Given the British brewing tradition and the emergence of craft brewing there, the historical scarcity of publications about cooking with beer seems a surprise. If we look to the twentieth century, there does indeed appear to be a dearth. In 1955, Elizabeth Craig observed that

the historical scarcity of publications about cooking with beer seems a surprise. If we look to the twentieth century, there does indeed appear to be a dearth. In 1955, Elizabeth Craig observed that

“[i]f there is one form of cookery that has been neglected more than another in Britain it is beer cookery…. There are plenty of books telling you how to introduce wine to fare, but few extolling the flavor of beer.” (Craig v)

She therefore set out to rectify the problem by writing Beer and Vittles, the source of her observation from 1955. Some of her material originates in Britain, or so she claims: Much of that, however, would appear actually to have originated with her or with some bowdlerized notion of how to prepare food in anything approaching an authentic way. The book includes some useful recipes that adhere to the British tradition, but they appear only after a series of unfortunate efforts at snack foods and party planning.

Craig was a prolific and bestselling British cookbook author for some four decades beginning in the 1930s. She wrote many of her books for “the housewife of modest income” and was known for practical, even parsimonious and austere recipes. They might have worked, at least some of them at times, under the strictures of rationing.

To a considerable extent, Beer and Vittles represents an attempt by Craig to unleash her inner good time girl. She cannot, however, quite cut loose. It is as if a studiously asexual grind were abducted from the library and dumped at a frat party. And yet Craig maintains--though it is hard to believe--that “[i]n my time I have been a guest at many gay beer parties…. One of the most amusing was held at a large beer-garden in Berlin” to celebrate the release of that year’s bock beer. People were “munching pretzels and wafer-thin slices of black radishes dipped in salt to whet their appetite for more beer. In between rounds they danced with zest.” (Graig 23)

This is not a bad way to begin a book about the pleasure that beer in the kitchen and on the table can bring to the proverbial party. The dancing sounds like fun, but not, it transpires, for poor Mrs. Craig:

“We sat it out, men drinking beer and me ‘peach bowl,’ until a flamboyant couple who had been celebrating too liberally crashed into our table and we thought it a good excuse for slipping away.” (Craig 23)

So off she goes, inspired by the jollity of others, to write her book on beer. As if to compensate for her own reticence, Craig awards imaginative names to a number of her recipes. Some aim to evoke a party spirit, others an exotic origin. She gives us bacon bunnies, canteen whoops, Chicago dip, Churchills, dirty Dicks, fiddle-de-dees, rainbow canapés, San Remo relish, Seville toast and others.

So off she goes, inspired by the jollity of others, to write her book on beer. As if to compensate for her own reticence, Craig awards imaginative names to a number of her recipes. Some aim to evoke a party spirit, others an exotic origin. She gives us bacon bunnies, canteen whoops, Chicago dip, Churchills, dirty Dicks, fiddle-de-dees, rainbow canapés, San Remo relish, Seville toast and others.

A bacon bunny is but a bridge roll stuffed with mustard butter, ham and cheese; no bacon, no bunny, no fanciful cottontail or rabbit ears. Cheese dough baked in roughly tubular shape to look (very little) like cigars are the ‘Churchills.’ The inadvertently amusing dirty Dick turns out to be made from grated cheese, egg yolk, ‘meat essence’ and caraway. Both the name and any purported connection to beer are entirely arbitrary.

Traditional British cheese rabbits get puzzling treatment too. Craig mislabels quite a few of them: The ‘American’ version in fact is a classic Welsh rabbit of Cheddar, beer, butter, egg yolk and mustard. In another attempt as false differentiation, Beer and Vittles misnames some rabbits rarebits. Her false rationale: “the modern versions are usually called Rabbits.” The term, however, is historically authentic, and ‘rarebit’ is an etymological impostor.

Craig’s Halloween menu includes ‘black cat’ and ‘white owl’ sandwiches, a ‘goblin’s platter,’ ‘witcheries’ and ‘wizards,’ along, incongruously, with a plate of Scottish chappit tatties. She appears to believe that any label would do; an automotive theme of tire iron and scissor jack sandwiches followed by a car thief’s platter, ‘drivers’ and ‘mechanics’ would have been no sillier than the spooked up versions.

If some of these names sound more than silly, others bear no discernable relationship to their stated points of origin. The Chicago dip, for example, includes cayenne, cheese sauce, cream, hard boiled egg, ham paste, horseradish and stuffed olives. While we might expect to find such a concoction in Oswell Blakeston’s Edwardian Glamour Cookery (Without Tears), we would never have found it in the Loop or any other Chicago neighborhood. None of the dishes Craig outlines for Hogmanay other than smoked salmon canapés to start and mince pies to finish sound remotely Scottish. Why not put those chappit tatties to use there instead?

In a further infelicity, Craig includes a recipe for “a catchup that will keep (1690).” The unconventional spelling is not the problem, for ketchup first appears in English as such in that year. No recipe for the condiment (whether spelled as catchup, catsup, ketchup or any other synonymous variation), however, would appear until the publication of The Compleat Housewife by Eliza Smith in 1727, and hers (which does not include beer) is not the version Craig deploys.

Craig’s selection of drinks incorporating beer amounts to a mixture of good and bad. Some of them are traditional combinations; variations on half & half, a self-explanatory combination of any two beers that the drinker chooses to order. The best of them has its own name, black velvet, a mixture of Champagne and stout that is the best of all things to drink with oysters.

Craig includes wassail too, and a number of lost drinks, including Dog’s Nose, a winter warmer from The Pickwick Papers. The Nose is a combination of hot porter and gin flavored with nutmeg and brown sugar, incongruous yes but weirdly bracing. It may be best to limit consumption, for Dickens’ Mr. Walker, an unfortunate convert to the wagon, “thought that tasting Dog’s nose twice a week for 20 years had lost him the use of his right hand.”

A patient reader also will find intriguing recipes for food in Cooking with Beer. Craig, however, appears to have made some of them up, and while we should welcome innovation, the inclusion of beer in traditional dishes that do not need it appears arbitrary too. She herself confirms our suspicion in several passages. The introduction to her section for sauces--many, she claims without attribution, from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries--offers the breezy advice that “[i]f you like the flavour of beer, but would rather use your own modern recipes for gravies and sauces, just include beer to taste in your ingredients.” (Craig 117) Why, then, does Craig include so many such recipes in the book when you can ad lib on your own?

innovation, the inclusion of beer in traditional dishes that do not need it appears arbitrary too. She herself confirms our suspicion in several passages. The introduction to her section for sauces--many, she claims without attribution, from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries--offers the breezy advice that “[i]f you like the flavour of beer, but would rather use your own modern recipes for gravies and sauces, just include beer to taste in your ingredients.” (Craig 117) Why, then, does Craig include so many such recipes in the book when you can ad lib on your own?

Elsewhere we find any number of editing errors. Cooking with Beer refers to Scotch eggs several times, and includes them in one of her set menus, but does not provide a recipe. The menus themselves annotate some, but not all, items with a series of asterisks ranging from one to six. What do they signify? We cannot know because the book does not tell us.

Nor do we know why recipes appear in inconsistent formats. Some list ingredients at the outset; some do not. Some appear as a narrative but others lead the reader through (nonnumbered) steps. These are not the kind of inconsistencies that a writer of Craig’s stature should have countenanced.

All this gives rise to the sad suspicion that Craig was putting out a potboiler in a hurry.

Even so, whatever we choose to call the various different kinds of beer and ale, Craig does provide workable recipes for most of them. If we take the time to do our own research, we also will find that some of those ‘older’ recipes are indeed traditional and they are good.

Medley pie sounds like one of those names that Craig concocted herself, but a little digging reveals that it is in fact a nearly lost traditional specialty from Derbyshire and Leicestershire; its name comes from the filling of beef, pork and apples spiced with ginger and bathed in ale.

Her ‘tavern cottage pie’ is interesting too, in advising her reader to bake the beef whole (while dicing is an option) under its bed of mashed potato; the use of rich and heavy, sweetish Scotch ale fits the rich and simple dish.

Poached salmon is an English classic; Craig’s variation for ‘thick steaks’ of the fish is an appealing option. She fashions what amounts to a courtbouillon using ale instead of water and wine, and the recipe embodies Craig at her best. After providing flexible proportions, she takes a brisk tone:

“Slice celery. Place in a shallow saucepan with shallots. Slice in carrots. Add butter and ale. Season with salt and pepper to taste. Cook slowly, covered, for about 15 minutes. Place the steaks side by side in a shallow fireproof dish. Cover with sauce, then cover. Cook in a slow oven, until salmon is tender, time depending on the thickness of the steaks. Dish up. Pour the sauce into the saucepan. Bring to boil. Boil, stirring constantly, until a creamy consistency and pour over fish. Garnish with champignons and sprigs of parsley and fingers of lemon.” (Craig 86)

These instructions are not only clear and concise, but sensible; it is unrealistic to give precise cooking times for something so variable as poached fish.

Steak and onions stewed in ale with anchovy, bay, cloves, mace and parsley represents an appealing variation on the English classic; while it should stand as common sense to boil ham in beer (the Editor has done so for decades) relatively few cookbooks provide a recipe. Craig does not commit the oversight.

We could go on; recipes worthy of note include a simple, quick stewed duck; an eighteenth century beer sauce for “boiled fresh-water fish” that marries equally well with roast pork; and a ‘steak gravy’ or homemade steak sauce that incorporates the juices from the cooked meat.

So, if we look past the tiresome persona that Craig needlessly adopts, Cooking with Beer would make a useful, even sprightly, addition to the kitchen shelf of any innovative cook of British food. A final note of caution: Please disregard her advice on the use of beer as a cleaning fluid, shampoo or ‘insect trap.’

Richard Boston demonstrates no interest in either insect traps or silly names that may or may not relate to beer. For two years, his purpose in “Boston on Beer,” a weekly column he wrote for the Guardian in the 1970s, was limited and laudable; the preservation of good cask ale via an explication of British public houses, brewers “and allied topics.” (Boston 12)

After that, “the polemical points had been made,” CAMRA had entered the fray and real beer had been saved, at least for a time. “Accordingly the column ceased to be exclusively about beer and pubs, and turned to other matters while continuing to make frequent trips to Publand.” (Boston 13)

The run of all those columns became a baseboard for Beer and Skittles, Boston’s meditation on traditional British beer and the culture it created in the public house. The book appeared in 1976 and, apart from a necessarily timebound discussion of available brands, remains as fresh today as it was back then.

Beer and Skittles may include the only comprehensible explanation of the term ‘original gravity’ ever written. It is worth repeating for those, like the Editor, who long remained mystified by it and never got a straight answer from anyone to questions about its meaning and significance. It “is the specific gravity of the wort,

or mixture of water, malt and yeast that will become beer, before it has started to ferment,” in other words a means of measuring something akin to weight for purposes of comparison:

“If the specific gravity of water is expressed as 1000 degrees [and it is for our purposes], anything above that figure in the specific gravity of the wort will indicate the quantity of malt and sugars present. When the yeast is added and fermentation begins, the sugars are turned into alcohol and carbon dioxide, and the specific gravity drops. The further it drops, the more alcohol there is. Usually the brewer stops fermentation when the gravity is about a quarter to a fifth of the original gravity. The percentage of alcohol by weight is about a tenth of the drop. Thus for example a beer with an o.g. of 1040 will contain about 3 per cent alcohol. Knowing the original gravity therefore does not tell you the precise strength, but gives you some indication of it.” (Boston 66-67)

In his discussion of Guinness, Boston also has the grace to highlight one of the best and funniest passages ever written about beer, by the peerless Flann O’Brien in At Swim Two Birds. It is a satirical poem, “The Workman’s Friend,” recited and received with reverence (“By god you can’t beat it. I’ve heard it praised by the highest… I’m telling you it’s the business”) by some immortal barflies. A representative verse:

“In time of trouble and lousy strife,

You still have got a darlint plan,

You still can turn to a brighter life--

A PINT OF PLAIN IS YOUR ONLY MAN!”

Among these many other matters that Boston chose to address was food, or more precisely food made with beer. A short subchapter called “The Cook’s Ale” muses on the effects both good and bad of Elizabeth David on British foodways before providing a small, well chosen selection of recipes.

This part of Beer and Skittles is no polemic. Boston liked David and she gave him “many helpful comments and suggestions about beer in cooking,” so helpful that he in turn gave her an acknowledgement. He feared, however, that her “enormously educational work” in introducing middle class Britain to the foodways of the wider world harbored an inadvertent virus.

David’s enthusiasm for all things foreign, and particularly French, threatened to traduce the island’s own cuisine:

“At times… it has seemed that while embracing foreign ways we have been in danger of forgetting our native traditions. The trendies of the swinging sixties could be relied on to turn out a passable coq au vin, but did they know how to cook a steak-and-kidney-pudding?” (Boston 114)

The trendies did, and do, not know how to cook much British food on either side of the Atlantic. Boston’s response to the question therefore remains more than timely. The point is simple, the beginning of a re-introduction to British foodways; the immediate if preliminary step “simply to suggest that beer belongs on the kitchen shelf every bit as much as wine does.” (Boston 114) After all, as he notes of Britain as late as 1975, “in many parts of the country ordinary bitter (as distinct from best) [was] called cooking beer.” (Boston 115)

He only wants people to try and, in the best British empirical tradition, eschews dogma or doctrine. The tone is modest:

“You can use beer in soups, stews and stocks; cheap cuts of meat can be greatly improved by marinading in beer; cheese and beer blend particularly well…. The best thing is to make your own experiments, but here are a few recipes to start with.” (Boston 115)

Boston presents fourteen of them along with some suggestions for “punches, mulled ale and the like.” (Boston 123) His superb sources range from Maria Eliza Rundell’s classic of 1806, A New System of Domestic Cookery, through a 1932 publication by the Women’s Institutes of Surrey to David herself.

The recipe from Mrs. Rundell, for stewed beef, is particularly interesting as the precursor of the ‘Sussex stewed steak’ described by both David and Jane Grigson, one of the best of all simple English dishes. It relies on a beguiling broth of beer, port, vinegar and mushroom  ketchup seasoned with a variety of sweet herbs and spice to transform the beef and create an addictive dish.

ketchup seasoned with a variety of sweet herbs and spice to transform the beef and create an addictive dish.

Boston had a particular predilection for cooking with Guinness, a trait the Editor shares. He likes ham with Guinness, oxtail simmered in the stout (“a great consolation in winter-time”), Guinness stew made with beef, and likes stout in his steak, kidney and oyster pudding, his kidneys, mushrooms on toast and Christmas pudding.

Beer and Skittles remains a small masterpiece nearly four decades on. It should make you smile and send you into a kitchen after a short detour to the beer supply. A pint of plain is indeed your only man.

Recipes for dishes incorporating beer appear in the practical.