The anomaly that is stew.

1. A food for the people.

We tend to consider stew ubiquitous across time and cultures. Pottage, essentially a thin, crude stew, stood as the staple of all British people from the Neolithic through Medieval eras, and nourished many of the poor in northern Europe until the end of the eighteenth century.

We tend to consider stew ubiquitous across time and cultures. Pottage, essentially a thin, crude stew, stood as the staple of all British people from the Neolithic through Medieval eras, and nourished many of the poor in northern Europe until the end of the eighteenth century.

Pottage consisted of any vegetables and grains to hand, supplemented in better times by fish or meat. During the Middle Ages variety usually was limited to garlic, leeks and onions with various herbs; grains mostly consisted of barley, oats or a mixture of the two. Wealthier households could add almonds, spice and wine to relieve the monotony of pottage, which boiled for hours into a homogeneous consistency. It must have been something like a thick gruel. (Amienne)

Some confusion now occludes this catchall for stew because vegetarians and vegans have hijacked the term to describe various mixtures of vegetables cooked in different ways. The usage is historically incorrect and need not distract us for long.

2. A stew by any other name….

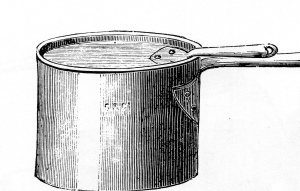

Despite the fact that the English always ate a lot of it, ‘stew’ does not appear to have been common usage as a noun until comparatively recent times and still makes only cursory appearances in bound British sources. You will look in vain for an index entry in any number of canonical cookbooks, including but not limited to the first edition of Mrs. Beeton, although ‘stewpan’ does appear. The byzantine index to Lady Clark of Tillypronie’s massive collection of recipes handed on from dozens of friends and other acquaintances includes no entry for beef, chicken, lamb, pork or veal stew, while ‘Irish Stew’ appears only within a category called ‘hotpot.’

As late as 1973, Michael Smith included only one stew, of mussels that actually is soup, in his wonderful Fine English Cookery. And in 1975, Elisabeth Ayrton included not a single stew (her usage is limited to the verb) in her remarkable survey of English foodways. It was nothing less than an effort to codify all of traditional English cuisine as its subtitle, a knowing reference to the style of seventeenth and eighteenth century cookbook titles, indicates.  The Cookery of England is a Collection of Recipes for Traditional Dishes of All Kinds from the Fifteenth Century to the Present Day, with Notes on their Social and Culinary Background.

The Cookery of England is a Collection of Recipes for Traditional Dishes of All Kinds from the Fifteenth Century to the Present Day, with Notes on their Social and Culinary Background.

3. Homely nourishment for Hard Times.

Poorer folks always have prepared stew from necessity and one of the few authors of British cookbooks to use the term as such addresses them in particular. Charles Francatelli, longtime chef to Queen Victoria and energetic philanthropist, printed his economical recipe for “Stewed Leg of Beef” in A Plain Cookery Book for the Working Classes. He uses only the verb in the title but goes on to describe the dish with the noun.

Francatelli knew his business and the cheap stew is good. The recipe is simplicity itself and bears quoting, for reasons historical as well as culinary:

“Four pounds of leg or shin of beef cost about one shilling; cut this into pieces the size of an egg, and fry them of a brown colour with a little [beef] dripping fat, in a good sized saucepan, then shake in a large handful of flour, add carrots and onions cut up in pieces the same as the meat, season with pepper and salt, moisten with water enough to cover the whole, stir the stew on the fire until it boils, and then set it on the hob to continue boiling very gently for about an hour and a half, and you will be able to enjoy an excellent dinner.”

He was right to specify shin and to boil it gently rather that cook it; it has more gelatinous collagen than other cuts so it yields a silken texture after slow cooking, but only if the temperature of the stock reaches 180° Fahrenheit, or just above the heat of simmer.

A twentieth century Englishwoman, Elizabeth Craig, wrote cookbooks that emphasized practical frugality. According to a contemporary Canadian journalist discussing cooks in Britain as well as Canada, “[i]t is her job to show them how to economize.” (Northern Gazette) Craig’s bestseller, Cooking With Elizabeth Craig, was first published in 1932 and reprinted for decades. It incudes but two stews, Irish and a rather eccentric ‘Exeter’ stew of beef and tomatoes that does not sound British, even though she explained in her subtitle that it was a “cookery book for the housewife of modest income.”

Do as I say, not as I look.

4. No room in the halls of academe.

Historians of British foodways tend to neglect ‘stew.’ Dorothy Hartley’s eccentric, sometimes bizarre and always enjoyable Food in England, which runs to over 660 pages, includes no index entry for stew and no discussion of it. She does discuss various ‘pots’ of meat, vegetables and flavorings, including beer, treacle and vinegar, but the meat in question simmers in a slab rather than in chunks. There is much discussion of savory puddings and all manner of obscurity but no stew, this in a volume called by scholars “a true source-book,” a “treasure-house of knowledge and delight” and “a classic, essential to our understanding of English food and cookery from medieval times to the early twentieth century.” (Luard, TLS, Norman on Hartley flyleaf)

Hartley may be eccentric but her omission of stew is no anomaly. It does not appear in other celebrated studies of British cooking, from The Englishman’s Food: Five Centuries of English Diet by Drummond and Wilbraham from 1939; John Burnett’s Plenty and Want: A Social History of Diet in England from 1815 to the Present Day, first published during 1966; C. Anne Wilson’s 1973 study, Food and Drink in Britain From the Stone Age to the 19th Century except for a reference (but no index entry) to “meat in stews, hashes and fricassees;” Philippa Pullar’s Consuming Passions: A History of English Food and Appetite (1970); or in Mason and Brown’s Traditional Foods of England: An Inventory, which appeared in 1999. The fact that stew was the commonplace food of the lesser ranks does not explain its scarcity as a noun in print; authors including Burnett, Pullar and Wilson address them as well as their wealthier compatriots.

5. Irish interlude.

A note is necessary on Irish stew, a dish of some controversy and great variation. Writers do refer to Irish stew with some frequency but it represents the atypical outlier (something like Ireland itself within the British Isles) rather than part of a general discussion.

6. Etymological origins.

The origin of the term lies either in the fourteenth century, with an early English verb derived from a term meaning “vessel for cooking (etymonline)” or with the Old French ‘estuier,’ “to shut up or enclose.” (FitzGibbon) The noun in widespread use today, however, does not appear until 1756, while “Irish stew is attested from 1814.” This initial usage in print apparently was by Byron, from Devil’s Drive, but in a strictly satirical and possibly fanciful way: “The Devil… dined on… a rebel or so in an Irish stew.” (Ayto)

It is fitting, at least as a reflection of British practice, that The Oxford Companion to Food leads its entry with a discussion of the verb. Theodora FitzGibbon reverses the order in The Food of the Western World (1976); perhaps her Anglo-Irish heritage made her more conversant with the noun than British contemporaries. She divides British stews into only two categories:

“For a brown stew, the meat, usually beef, is browned in fat before the vegetables and liquid are added. A white stew is made with mutton, chicken, or fish; the classic example of a white stew is Irish stew.” (FitzGibbon)

7. Things differ across the western sea.

In 1981, a British author called Jane Garmey did list five dishes under the index heading “stews” in her unpretentious and engaging Great British Cooking: A Well Kept Secret. Then again, Garmey had lived in New York for nineteen years and married a man from Pittsburgh: Her book was published in the United States for an American audience.

In 1981, a British author called Jane Garmey did list five dishes under the index heading “stews” in her unpretentious and engaging Great British Cooking: A Well Kept Secret. Then again, Garmey had lived in New York for nineteen years and married a man from Pittsburgh: Her book was published in the United States for an American audience.

Mrs. FitzGibbon aside, American and British usage had diverged by the nineteenth century. American cookbooks, in contrast to their British counterparts, are replete with dishes called stews. A quick look at Boston alone reveals a lot of them described by bestselling authors like Mary J. Lincoln and Fannie Merritt Farmer. Their contemporary Philadelphia counterpart, Mrs. Rorer, also includes several recipes for ‘stew.’ By 1997, James Villas would devote an entire book to stews along with bogs and burgoos, which are colloquial southern terms for… stew.

When did Americans adopt the noun? It is hard to say. In 1796, Amelia Simmons included a recipe she calls “stew pie” in American Cookery, the first recognizably American cookbook but the reference cannot count. In context the recipe is for a pie made from layered veal, salt pork and biscuit dough that you stew, a ‘stewed pie;’ so in common with contemporary British practice Simmons confined herself to use of the verb. Forty-eight years later the great Eliza Leslie also uses only the verb in her Directions for Cookery (and does not include a reference even to Irish stew.)

8. The emergence of convergence… if only up to a point.

Things have changed and usage now converges on both sides of the Atlantic. A trend toward the term, however minor, did emerge during the 1970s among some ambitious British cookbook authors, even if many dishes indexed under the heading of ‘stew’ bear a different name. Jane Grigson lists five in English Food from 1974; Lizzie Boyd’s comprehensive guide to culinary practice in the British Isles, a book its publishers hoped would become a British Larousse (alas) indexes some three dozen stews in 1979. In her view, hotpots require separate listing.

9. Stew that’s old is new again.

Yet while current British sources show no reticence in referring to stew, it tends to be of a single kind. In an echo of Francatelli and Mrs. FitzGibbon, the overwhelming number of internet search results for ‘English stew,’ ‘traditional English stew’ and similar iterations generates the same result, a beef stew with onions, root vegetables and sometimes potatoes, usually simmered in water or stock but sometimes with red wine or various beers. Boyd’s collection of recipes provides inferential evidence of this predominant usage: Seventeen of her stews are regional variations based on beef.

Yet while current British sources show no reticence in referring to stew, it tends to be of a single kind. In an echo of Francatelli and Mrs. FitzGibbon, the overwhelming number of internet search results for ‘English stew,’ ‘traditional English stew’ and similar iterations generates the same result, a beef stew with onions, root vegetables and sometimes potatoes, usually simmered in water or stock but sometimes with red wine or various beers. Boyd’s collection of recipes provides inferential evidence of this predominant usage: Seventeen of her stews are regional variations based on beef.

A typical example appeared in the Guardian two years ago. The unnamed (at least online) author of an article in its “Word of Mouth” blog assumes that her readers equate British stew with beef stew. The Guardian goes further, to equate British beef stew with something similar to what Francatelli, whom she cites, describes in his Plain Cookery Book. The subtitle of the article asks a question that sets the tone: “Can British beef stew hold its head high in the face of international competition?” (Guardian)

It begins by noting the postmodern disdain for traditional stew in Britain.

“But while other nations celebrate such peasant cuisine, Britain has largely abandoned its own recipes in favour of daubes, bourguignons and osso buco--a tendency not helped by the word ‘stew’ [Editor’s note: They just do not like the noun.] with its gristly overtones of school dinners and slow-burning resentments. Stewing is an activity for disgraced politicians and lovestruck teenagers, not a precursor to dinner.

Tellingly, Plat du Jour, Jane Grigson’s favourite one-pot cookery book, which was first published in 1957, includes recipes for goulash and stroganoff, and an extravagant two for daube, but nothing for anything as boring as a British beef stew.” (Guardian)

This perspective may or may not make sense in singling out a British antipathy toward its native stew, for from the midpoint of the twentieth century until recent times, British people displayed an antipathy to most of their culinary tradition.

Mrs. Grigson never was any such snob, and included not just British beef stew in English Food, but none other than Francatelli’s rendition. It was a favorite dish in her family for generations. She did note, however, that “stock, or better stock and red wine, can be substituted for the water,” either way a salutary substitution. (Grigson 142) Then do as the Guardian did. Resist any temptation to toss potatoes into the pot and serve your stew with fluffed up dumplings. The stew is, in the typical tone of British self-deprecation that the Guardian frequently adopts, “surprisingly decent for something so uncompromisingly plain…. ” (Guardian)

Mrs. Grigson herself provides more than a hint why ‘stew’ appears so infrequently in British imprints of the later twentieth century. She would never serve Francatelli’s stew the way he intended but instead sliced the meat to serve over separately cooked potatoes and glazed carrots. Why? “It does not look in the least like a stew” that way:

“I always serve meat and sauce separately, because the older members of the family cannot bear the sight of a stew after their early institutional experiences.” (Grigson 142)

At least the British dare say stew today. All of this is odd to an American eye, because the traditional British kitchen produces many different buckets of things that look and taste like stews. The British simply decline to call them that. They historically cook braises, China chilo, coddles, fricassees, hotpots, kettles, lobscouse, ragoos, watersouchy and of course curries instead.

Recipes for stew, whether or not we call them that, appear in the practical, along with recipes that stew ingredients together.

Sources:

Anon., “How to cook perfect beef stew,” the Guardian (3 February 2011)

Anon., “Pep Up Fish Day,” Peace River, Alberta, Northern Gazette (9 April 1937)

Elisabeth Ayrton, The Cookery of England (London 1975)

John Ayto, The Diner’s Dictionary (Oxford 1993; orig. publ. as The Glutton’s Dictionary, London 1990)

Isabella Beeton, Beeton’s Book of Household Management (London 1861)

Lizzie Boyd (ed.), British Cookery: A complete guide to culinary practice in the British Isles (Woodstock NY 1979)

John Burnett, Plenty and Want: A Social History of Diet in England from 1815 to the Present Day (London 1966)

Alan Davidson et al., The Oxford Companion to Food (Oxford 2006)

J. C. Drummond & Anne Wilbraham, The Englishman’s Food: Five Centuries of the English Diet (London 1939)

www.etymonline.com (“The Online Etymology Dictionary”)

Fannie Merritt Farmer, The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book (Boston 1896)

Theodora FitzGibbon, The Food of the Western World (London 1976)

Jane Garmey, Great British Cooking: A Well Kept Secret (New York 1981)

Jane Grigson, English Food (London 1974)

Dorothy Hartley, Food in England (London 1954)

Eliza Leslie, Directions for Cookery in its Various Branches (Philadelphia 1848)

Mary J. Lincoln, The Boston Cook Book (Boston 1883)

Laura Mason & Catherine Brown, Traditional Foods of Britain: An Inventory (Totnes, Devon 1999)

Philippa Pullar, Consuming Passions: A History of English Food and Appetite (London 1970)

Sarah Tyson Rorer, Philadelphia Cook Book: A Manual of Home Economics (Philadelphia 1886)

Amelia Simmons, American Cookery (Hartford 1796)

Michael Smith, Fine English Cookery (London 1973)

James Villas, Stews, Bogs & Burgoos: Recipes from the Great American Stewpot (New York 1997)

C. Anne Wilson, Food and Drink in Britain From the Stone Age to the 19th Century (London 1991)