New Orleans: A Food Biography is badly written, promotes anachronism & traduces the British culinary tradition.

The AltaMira Press has launched a series called “Big City Food Biographies.” It is fitting that New Orleans is the first subject, of New Orleans: A Food Biography by Elizabeth M. Williams, for no city in the United States claims a more varied, controversial and eccentric indigenous cuisine.

The Food Biography represents an astonishing achievement. It is so inaccurate in nearly every respect, and so badly written, that readers may be forgiven if they mistake it for parody. The author is not the lone culprit; her editor at AltaMira has ensured that the book is repetitive and loaded with infelicities. With luck it will turn out to be the only volume in the series.

Williams begins what she passes off as analysis with the premise that the Enlightenment created the foundation of New Orleans foodways, and that the predominant influence on the unique cuisine of the city is French haute cuisine as codified by La Varenne.

Williams believes that Louisiana always has existed in the close orbit of metropolitan France. “Being a part of the Republic of Letters meant,” she claims, “that French Enlightenment approaches to living were adopted in New Orleans.” (Williams 18)

These “Enlightenment approaches to living” never are described, but apparently have something to do with the acceptance of new ideas:

“Unlike other places in the Americas that also had Europeans, including French, Africans and Native Americans present during the colonial period, the French ties of the colony allowed the colonists not only to substitute ingredients from the Old World with New World ingredients, but to let them evolve into a New World food…. Allowing the continuing change represents the French influence and attitude. It is this French attitude born of the French Enlightenment that set the stage for the development of the cuisine.” (Williams 18-19)

Leaving aside for a moment the ghastly prose and possibility that an African or Native American might find it startling to be considered European, in fact France never had much use for its squalid colony on the Gulf of Mexico. Nor did French sovereignty last long, and during some fifty years of nominal and interrupted governance, France starved the colony of resources. Louis XIV and Napoleon were so jealous of manpower for their armies that their regimes discouraged emigration.

French settlers did not account for the burgeoning population of New Orleans toward the end of the eighteenth century: It resulted from an influx of other nationalities, notably enslaved Africans beginning in 1719, barely a year after the founding of the town, Germans from 1724 and British North Americans soon after that. Following independence, so many Americans surged down the Mississippi into the city that its eventual annexation would have been a foregone conclusion without the Louisiana Purchase.

Even if the fledgling colony had had much in the way of significant communications with France, it is difficult to imagine how any such contacts encouraged the substitution of ingredients, which do not themselves “evolve into a New World food” or anything else.

Enlightenment ideals had nothing to do with the substitution of indigenous foodstuffs; early colonists resorted to them from unanticipated necessity. As Emeril Lagasse observes, the early settlers “found themselves at a loss for the traditional ingredients of French cooking to which they were accustomed. The spices and herbs, the meats of their homeland were not available in the beginning.” (Lagasse xiii) The French never did manage to grow wheat, their staple back home, in the damp climate of southern Louisiana. Its cultivation would await the arrival of Palatine Germans.

Germans dominated the cultivation and sale of produce for consumption in New Orleans from the “Côte Des Allemands” twenty-five miles upriver even at the inception of French rule. According to Susan Tucker, “[b]y 1850, German was more apt to be spoken than French, and German newspapers and schools rivaled those exclusive to the French and Americans.” (Tucker 12) Gumbo des herbes, or gumbo z’herbs, a Lenten tradition in New Orleans, derives from the German custom of eating a soup made with seven greens on Maundy Thursday. (Folse 86) Ponce, another peculiarity of Louisiana, descends in direct line from German stuffed pork stomach.

If Williams were referring to a culinary tradition derived, perhaps, from popular practice or folk memory, her conclusions might make some sense. It is clear, however, that she considers the ‘refined’ cooking of La Varenne the primary antecedent of Louisiana cuisine as we know it.

La Varenne

It is impossible to fathom how the rigid precepts of his classical haute cuisine encouraged substitution or evolution. To the extent that the Enlightenment may have intruded on the thoughts of La Varenne, it was in the guise of his attempt to codify a lofty stratum of French cuisine rather than extol innovation. As Alexandra Guarnaschelli has said of her apprenticeship in Parisian restaurants:

“There is a system for everything, a way to do it. You can’t cut a fish that way because ça n’est pas bon. You can’t bone a chicken that way, because that’s not good…. You never get a real attempt to innovate, or to use new flavors.” (Gopnick)

That is La Verenne’s legacy, an invitation to stasis instead of an embrace of novelty.

Williams’ placement of him and his opus, Le Cuisinier française, entails considerable confusion. She describes La Varenne first as “cuisinier to a French nobleman,” then as “the celebrated chef to Henri IV” before linking him to the Sun King:

“The French Chef … included… innovations besides its references to the refinement of food and the raising of cooking and eating to the same level of French arts, French refinement, and French luxury as other aspects of the reign of Louis XIV.” (Williams 7)

These three incarnations appear on a single dissonant page. Williams never identifies the noble (he was the Marquis of Uxelles; La Varenne coined the term duxelles in his honor). It would have been difficult for La Varenne, who was born in 1615, to cook for Henri IV; the king had been assassinated five years earlier, forty-one years before Le Cuisinier first appeared in print. As for Louis XIV, nothing links La Varenne himself to either the Tuileries or Versailles.

Nonetheless his style did embody what historians call court cuisine, food for kings, aristocrats and their hangers-on. It emphasizes expensive ingredients and sumptuous display. As such it is antithetical to Enlightenment precepts of equality and rationality. Incidentally, Bonnefon and Massialot contributed as much to court cuisine as La Varenne but get no mention from Williams. It would remain much in vogue at palaces on both sides of the English Channel throughout much of the seventeenth century.

Williams’ problem runs deeper than her misplacement of La Varenne, because she provides no factual basis for the assertion that Enlightenment philosophy had much to do with the development of foodways anywhere, let alone New Orleans. In commonsense terms it would be difficult to imagine a city in the western world less defined by Enlightenment concepts of order, logic and deductive reasoning.

If the Enlightenment did have anything to do with food, nothing justifies Williams’ emphasis on its French strain. The Enlightenment itself was an international phenomenon, and during the eighteenth century English publishers produced thousands more copies of cookbooks than their counterparts in France. The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy by Hannah Glasse, for example, which disdained French food, was the biggest selling book in the world on any subject during the 1700s, with the possible exception of bibles and pornography.

Williams confines the Enlightenment to Europe, “most notably” France and England. This of course disregards North America (Bartram, Franklin, Jefferson, Madison, Rush) while ignoring Scotland (Ferguson, Hume, Smith) and the ‘Greats,’ Frederick of Prussia and Catherine of Russia, not to mention developments in Sweden (Linnaeus) and elsewhere. This Stalinization of the past does leave England standing alongside France, but that presents no problem. To Williams, its cuisine is irrelevant.

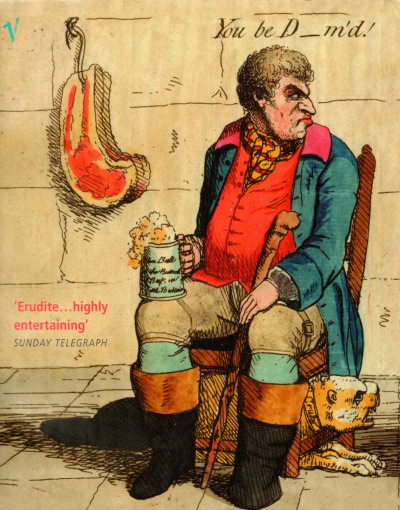

Her dismissal of England when it comes to food is both hackneyed and facile. “Eating, as culture and as art, was not a popular notion in England or in the English-influenced colonies in the New World.” (Williams 98) We need look no farther than the diaries of Parson Woodforde, however, to appreciate the convivial relish with which the eighteenth century English gentry consumed their food.

English food at the time was held in considerable esteem, not only at home, as Hogarth demonstrates with “The Gate of Calais,” but also abroad; French gourmands travelled to sample the food at the famed London Tavern and a bestselling cookbook, The London Art of Cookery, purported to replicate its dishes. Authors as varied as Keith Stavely, Kathleen Fitzgerald, Joyce Chaplin and Hannah Acton have documented the sophisticated foodways and cultivation patterns of North American colonists from New England all the way down to the Carolina low country.

In Charleston, Sean Brock has reinvented the southern table by reference to vanished Anglo-American foodways. He cultivates landrace seeds descended from lost crops and creates dishes inspired by printed sources like The Carolina Housewife, kitchen manuscripts and plantation records from the colonial era through the first half of the nineteenth century. His restaurant, Husk, may now boast the most difficult reservation in America.

Sean Brock at Husk

All those early cookbooks by Hannah Glasse and other British authors made enthusiastic use of spices, herbs as well as other seasonings like anchovy and citrus; as one writer has noted, cayenne was the pungent taste of empire. English cuisine, like the language, was promiscuous and happily adopted outside influences to create a coherent and creative eighteenth century cuisine.

In reality, the food of New Orleans shares nearly nothing with the rigid precepts of classical haute cuisine. It does share some but by no means all language, but beware: French names can mean different things in Louisiana than in Europe. Louisiana remoulade neither tastes nor looks like the sauce found in France; the same goes for Bordelaise. Sausages that sound French, like andouille, claim descent from German species, and boudin bears no resemblance to its French namesake either.

John Folse, who has opened his own restaurant, R’evolution, to explore the antecedents of New Orleans cuisine, identifies seven bedrock influences on the food of the city. His Encyclopedia of Cajun & Creole Cuisine, which Williams ought to have consulted, includes an essay covering them all. Native American, French (and its offshoots from Acadia and San Domingue), African, German, Italian and… English foodways all get their due (Lagasse concurs with the listing, xiii-xiv).

The peacemaker or oyster loaf had appeared in the streets of London before the foundation of New Orleans, both cities shared an affinity for turtle soup, Natchitoches pies bear more than passing resemblance to pasties, settlers feasted on roast goose or pork with apples and boiled salt beef brisket, Fergus Henderson’s ‘real John Bull’ (still a standard, if bathed in Sauce Creole, in the New Orleans kitchen), got them through the winter. A fricassee from Richard and Rima Collin’s New Orleans Cookbook, seasoned with allspice and cayenne, looks a lot more like something diners would have found at the London Tavern than the pale version they could order in a contemporary Parisian restaurant.

None of this is to deny that a French influence may be primus inter pares on the food of New Orleans, but it is not the influence that Williams identifies and is not the only one.

Factual errors on a lesser scale permeate the Food Biography. It is wrong to claim, as Williams does, that “England had recognized a certain level of popular rights as early as the Magna Carta in 1215.” (Williams 98) The charter gave the barons powers related to taxation but did not enfranchise any commoner. Catastrophic famines beset Ireland from 1740-41 and 1845-52, not 1820-40; Hispaniola is not synonymous with San Domingue, now Haiti, which shares the island with the Dominican Republic.

Contradiction and repetition abound. At one point Williams takes Lafcadio Hearn’s description of nineteenth century dishes at face value, while elsewhere she points out, properly, that Rien Fertel has demonstrated Hearn lifted recipes from non-New Orleanian sources. Then she repeats the same observation forty-four pages later.

At some points the prose is unaccountably inane. It is impossible to parse a statement like

“[w]hen the French began to colonize what was to become New Orleans, they found the raw materials of a cuisine. The foods that were available in New Orleans were already identified. This is an extraordinary advantage in the process of developing a cuisine.” (Williams 9)

Does Williams mean that colonists did not fail to see foods, or that without food there is no cuisine? Does she consider it extraordinary that raw materials existed in Louisiana? It would appear that without food there could be no life at all. Whatever she meant, Williams contradicts herself in the next sentence:

“Although the journals and records of the French who were the first settlers indicated [sic] a wilderness, the assessment did not recognize the pantry that had been created by the Amerindians.” (Williams 9)

Williams, however, is not finished, for she then ‘explains’ that “in spite of the wilderness that the French found, the raw materials were available, not hidden.” (Williams 9) If we take Williams’ prose at face value then these settlers must have been dunces not to notice this ‘pantry’ and these ‘raw materials’ hiding in plain sight.

Her editor bears much of the blame for allowing train wrecks like this to serially embarrass her author throughout the book. The editing is so slapdash that a notation in bold face and brackets, “Please supply page ranges of article” is appended to an essay from Gastronomica that appears in the bibliography of the published volume.

It is a shame that New Orleans: A Food Biography is so awful, for the story of the city and its foodways is unique and enthralling. All is not lost, however; New Orleans Cuisine: Fourteen Signature Dishes and Their Histories, edited by Susan Tucker, does not pretend to be a comprehensive survey but makes an excellent start. Its contributors have written scholarly and entertaining essays on subjects from turtle soup to bread pudding which, incidentally, originated in England.

Sources:

John Folse, The Encyclopedia of Cajun & Creole Cuisine (Gonzales, LA 2005)

Adam Gopnick, “Is There a Crisis in French Cooking?,” The New Yorker (28 April 1997)

Emeril Lagasse, Louisiana Real & Rustic (New York 1996)

Donald Link, Real Cajun: Rustic Home Cooking From Donald Link’s Louisiana (New York 2009)

Susan Tucker (ed.), New Orleans Cuisine: Fourteen Signature Dishes and Their Histories (Jackson, MS 2009)

Elizabeth M. Williams, New Orleans: A Food Biography (Lanham, MD 2013)