An Appreciation of the Pudding Lady, embedding commentary on recent books by Maggie Andrews & Ellen Ross.

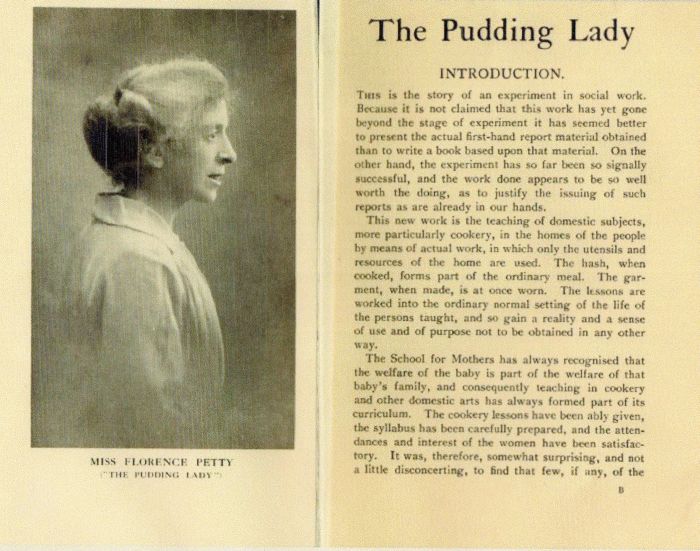

She does not appear in Who’s Who or Who Was Who and Oxford has not included her in its Dictionary of National Biography. Her place of birth was Montrose, Scotland, during 1871. Neither The Times of London, nor apparently any other newspaper of record, appears to have published an obituary following her death in 1948.

Between these bookends we know nearly nothing about her family or personal life.

The publisher of a text including a brief description of her work describes this woman as someone who has “languished in obscurity.” (Taylor & Francis) She remained single: The newspapers sometimes referred to her as ‘Miss’ but more often as ‘The Pudding Lady.”

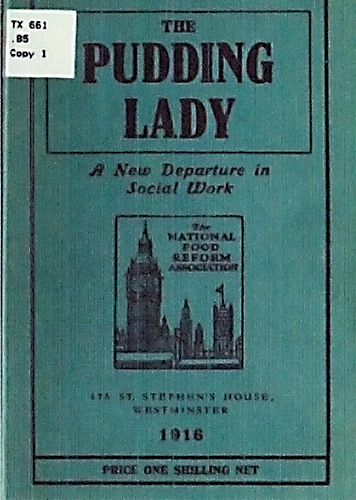

This obscurity entails a certain historical disjunction, for the Pudding Lady once was what we now call a celebrity. She published the influential Pudding Lady’s Recipe Book; it sold tens of thousands of copies and remained in print for over a decade. The book was a vehicle for her life’s work of improving the nutrition of the British working poor.

She lectured tirelessly at hospitals, schools and other assemblies for the National Food Reform Association (later renamed the Food Education Society) and, with the onset of the First World War, the Ministry of Agriculture. In 1922 alone she gave over one hundred lectures; by late January of 1923 she already had lined up over eighty more for the year. (Times, “Diet and Hygiene”)

She lectured tirelessly at hospitals, schools and other assemblies for the National Food Reform Association (later renamed the Food Education Society) and, with the onset of the First World War, the Ministry of Agriculture. In 1922 alone she gave over one hundred lectures; by late January of 1923 she already had lined up over eighty more for the year. (Times, “Diet and Hygiene”)

During the interwar period she also became one of the most popular broadcasters on BBC radio as a frequent participant in its “Household Talks” series.

The Pudding Lady enjoyed more than a measure of success. One of her colleagues at the Food Education Society said of her tract that “[f]resh evidence is constantly accumulating of the extraordinarily widespread influence exerted by this book” and this in 1910, before the radio years would expose her to exponentially more people. (Bibby et al. x) What she did was in its way revolutionary.

By the outset of the twentieth century, a slew of commentators emphasized how far cooking skills in Britain had eroded all along the class continuum. John Sykes of the Society was one of them. He observed that “nothing is more striking in urban centres during the present generation than the diminution of cookery at home, not only amongst the richer, but also amongst the poorer classes.” (Bibby et al. 13)

As usual the ‘poorer classes’ bore the brunt of the decline. Sykes identified two reasons, the “increase in woman’s labour away from home” and the lack of kitchen facilities in overcrowded dwellings due to “the packing of many families in houses constructed originally for only one, so that the separate dwellings have not the fittings necessary for a complete dwelling.” (Bibby et al. 13)

In response the Food Education Society therefore “had come to the conclusion that nothing short of individual teaching in the homes would really solve the question of the proper feeding of the children….” (Bibby et al. 24-25)

Florence Petty was the one who first had the insight to realize that cooking schools then in existence were tantamount to useless for the audience that needed them most: The tools at the schools were absent from their kitchens and the recipes beyond their skill or means.

The St. Pancras School for Mothers in London, which strived to serve “the very poor population” west of Euston Station, had tried in vain to teach the needed skills onsite. Petty decided to visit the wives of the working poor instead. She “befriended women attending classes” at St. Pancras “and offered to give them lessons in their own homes using the fuel, pots and ingredients that they normally used.” (Ross 192)

E. G. Colles of the Society explained why this benign incarnation of home schooling worked:

“It may sound absurd, but those who have a working knowledge of the welcome mothers know that is is true that a woman will remember how to do a thing when she has the same bowl and the same saucepan and spoon and table for her use which were used at the lesson, whereas if the cooking is done in a separate room she will forget it. The setting recalls a train of ideas….” (Bibby et al. 25)

It would be anachronistic to dismiss Colles as merely elitist and patronizing. He was writing for an audience that, unlike Petty, had nearly no contact with the poor and none at all with their domestic conditions. His brief was to extend the program by pleading for its necessity in language they might understand.

Portrait of a (Pudding) Lady

Not that the goals of the Food Education Society were exclusively humanitarian; they were nationalistic as well. Charles E. Hecht wrote Rearing an Imperial Race in 1913 and in 1923 Petty herself contributed “The Cook as Empire Builder” to the Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health. We cannot, however, impugn their motives. They did care for the welfare of the poor. It is simply the case that these reformers cherished an overt patriotism that has gone out of style except among the more doltish members of the Tea Party.

Both the humanitarian and nationalist themes get echoed in The Pudding Lady’s Recipe Book. “Every good cook or housekeeper is, in these days, a patriot” (this in 1917) and some years after the war Petty warns her reader that “a still wider knowledge of foods and their treatment is needed if we are to become a great nation.” (Recipe Book 5, 7) At the time Britain did consider itself a great nation in global terms, but while some reformers like Petty applauded the nation’s power, it could not achieve a more existential greatness without the eradication of poverty and even, in the view of the Fabians, of inequality itself.

Petty for one was well-received by her charges. It was their children who named her The Pudding Lady and it easy to see why. Colles is right to categorize the notes of her visits reproduced in the 1910 edition of the Society’s Pudding Lady: A New Departure in Social Work as revealing “the sympathy and considerations which are needed to carry the teacher safely through such a difficult task as the instruction of a mother in her own special stronghold, the home.” (Bibby et al. 25)

Petty’s diary notes, or case studies, are matter-of-fact but also sympathetic rather than clinical, and record with care the conditions she encountered as well as the pedagogical and culinary techniques that proved successful. In The Pudding Lady’s Recipe Book, she writes with a gently hortatory and yet homely touch; hers is hardly the hectoring voice of so many reformers.

At the outset she explains:

“Cooking is both a science and an art. When once we have grasped this important fact, it is no longer the drudgery that so many have imagined. There is joy in the very thought of turning out an attractive and appetising dish and there is something very satisfying in using both hands and head in the creation of a masterpiece.” (Recipe Book 5)

Petty also reassures readers that they need not master difficult technique nor muster myriad exotics to keep their food creative. “As knowledge of the subject grows, the same recipe need not be exactly repeated. A change of even one of the ingredients gives a different flavour, and thus a new dish is evolved.” (Recipe Book 5)

All this is sound, and timeless, advice to anyone from any social stratum who lacks experience in the kitchen.

As for the children, she may have charmed them but certainly catered to their tastes. Traditional, and irresistible, British suet puddings, the majority of them sweet rather than savory, crowd the pages of The Pudding Lady’s Recipe Book. They get its biggest chapter and fill the longest index entry.

In Domesticating the Airwaves, Maggie Andrews describes Petty’s broadcast style in the “Household Talks” as “homely, economical and pragmatic.” (Andrews 37) She must have been courteous too, for it is difficult to believe that she secured invitations from all those disadvantaged women for all those years if she had not treated them with dignity.

The ‘Talks’ presented Petty with an ideal platform. The BBC aimed them at working class “housewives on whom the burden of domestic survival fell.” (Andrews 36) Managing a family’s meager resources was paramount, and reasonably enough Petty urged her listeners to make food their priority: “Health, as everyone knows, is the most important thing in life and if the income is small, the amount apportioned to food must come first.” (Andrews 36-37, citing BBC archival material)

If food must come first it may be expensive, and that is where The Pudding Lady’s Recipe Book rides to the rescue. Like the radio broadcasts, the cookbook emphasizes economy. Most recipes use at most a handful of inexpensive items.

Soup stocks may be made from “vegetable skins and cheese rinds,” margarine displaces butter throughout and Petty stretches her sea pie by adding shredded vegetables to the beef. (Recipe Book 43, 95) The Recipe Book minces many ingredients but no words. It includes a “Cheap Christmas Pudding,” “Half Pay Pudding” and “Economical Fritters.”

Some of her tips and recipes prefigure the Ministry of Food’s efforts to convince the populace that substitution of humbler for familiar methods and ingredients is worthy, even enjoyable. There are instructions for constructing a “makeshift” oven from a biscuit tin for those lacking the real thing, and for making a haybox from newspaper:

“Advantages,

1. No fuel is wasted.

2. No attention is needed while in the box.

3. Nothing can be overcooked.

4. No nourishment or flavour is lost.” (Recipe Book 103, 104)

The batter for Petty’s toad in the hole dispenses with expensive eggs. Her cookbook devotes one chapter to “Potato Recipes,” essentially a means of using them to replace flour in pastries with, and another to “Meat Substitutes” that relies heavily on nuts and pulses. There are predictably grim recipes for ‘maize rissoles’ and ‘mock veal cutlets;’ elsewhere, the lowly rabbit replaces the real bird in a ‘squab pie.’

For all their emphasis on economy, many of the recipes are not bad. They tend to simplicity, not unlike homely renditions of the dishes in Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall’s Three Good Things on a Plate. The rabbit pie by another name is one of them. So is the ‘celery and cheese soufflé’ from the chapter of “Meat Substitutes,” actually a batter pudding good enough for the most prosperous table. This sort of thing is more a nice alternative than a dreary substitute.

For all their emphasis on economy, many of the recipes are not bad. They tend to simplicity, not unlike homely renditions of the dishes in Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall’s Three Good Things on a Plate. The rabbit pie by another name is one of them. So is the ‘celery and cheese soufflé’ from the chapter of “Meat Substitutes,” actually a batter pudding good enough for the most prosperous table. This sort of thing is more a nice alternative than a dreary substitute.

Sometimes the need to stretch expensive ingredients proves serendipitous. ‘Steak & bean pudding,’ in fact a steak and kidney pudding made more economical and nutritious with the addition of beans and carrots, suffers not at all from their presence. ‘Meat Stew’ also exploits the bean. It in fact is a simplified sort of cassoulet. On occasion Petty’s effort to economize improves the flavor of a preparation. Her stuffing for turkey is one. It takes the familiar sage and onion stuffing a step further by adding egg, liver, oatmeal and sausage. It would enhance any other biggish bird, like a chicken or goose, as well.

Not all of the Pudding Lady’s recipes represent economical innovations. There are all those English puddings. The ingredients for pease pudding are cheap enough on their own, so Petty prepares it in the traditional manner rather than altering the dish in the interest of economy or novelty. Cheshire pie represents another example. Bill Murray would be proud.

We should all take pride in the memory of Petty too. Andrews, however, is a bit unkind about her. She notes, rather sourly, that Petty’s advice, “which included drinking cabbage water [but where? Not in The Pudding Lady’s Recipe Book], would not always have stood up to scientific scrutiny.” (Andrews 37) Perhaps not now but probably then it did; this is nothing but anachronism.

In fact Petty displays a remarkably modern sensibility. She advocates eating lots of salads and describes quite a few of them, does not overcook her vegetables and is utterly accurate to comment that “[u]npolished rice should be used. Polishing removes the most nourishing part.” (Recipe Book 101) Fish ought to be ‘boiled slowly’ in water laced with a little lemon juice or vinegar. (Recipe Book 27)

Elsewhere Andrews claims that “the basis on which Miss Petty and other domestic experts felt able to instruct the working-class housewife was open to debate and liable to be fiercely contested.” (Andrews 37) That comment also appears misplaced. It hardly seems debatable to “insist upon” the “great importance” of feeding babies at the breast (Bibby et al. 19), put food first in the domestic budget or help anybody, whatever her social stature, learn how to cook.

None of the admittedly paltry sources that mention Florence Petty invoke controversy. Instead they display unalloyed admiration. Her colleague Charles Hecht at the Society, for example, apparently considered Petty primus inter pares. He calls Petty a “heroine” and considers her contribution “a valuable piece of pioneer social work,” even “a standard work for social reformers.” (Bibby et al. ix)

“The Pudding Lady” had become a potent symbol, one that had come to stand “for more than an individual. It represents an attitude of mind and a definite method of handling a difficult social problem,” improving the hardscrabble lives of the urban underclass and particularly their children. (Bibby et al. ix)

Petty herself, Hecht thought, had “become a public possession, bringing to bear on the solution of national problems those rare gifts of heart and head and that unique experience which achieved such wonders” in the kitchens of the working poor. (Bibby et al. ix)

These effusive assessments are all the more impressive because they appeared in 1910, near the outset of a career that would continue at least until the eve of the Second World War. The Glasgow Herald reported in 1938 that, at the age of sixty-seven, the indefatigable Petty “refuses to retire, and to-day is a valued demonstrator,” still “teaching economical cookery and food values in the poorest homes.” (Glasgow Herald) Perhaps she had little choice; Petty left effects worth only £66.7d when she died a decade later.

Like Hecht, the Herald considered Petty a pioneer, and described her with understated pride as a “Scotswoman who in her own way has achieved fame,” still affectionately known forty years on as “The Pudding Lady.” (Glasgow Herald) Now, a half century later, the world has forgotten her.

Florence Petty’s biographer awaits.

A selection of her recipes appears in the practical.

Notes:

Maggie Andrews, Domesticating the Airwaves: Broadcasting, Domesticity and Femininity (London 2012)

Anon., “Diet and Hygiene. Food Education Society’s Appeal,” The Times (London) (24 January 1923)

Anon., “The Pudding Lady & A Pioneer Cookery Teacher,” The Glasgow Herald (6 December 1938)

Miss Bibby, Miss Collins, Miss Petty & Dr. Sykes, The Pudding Lady: A New Departure in Social Work (London 1910)

Charles E. Hecht, Rearing an Imperial Race (London 1913)

Florence Petty, “The Cook as Empire Builder,” Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health vol. 44 no. 267 (1923)

Florence Petty, The Pudding Lady’s Recipe Book (London, 13th ed. 1928)

Ellen Ross, Slum Travelers: Ladies and London Poverty, 1860-1920 (Berkeley 2007)

Taylor & Francis publishers, www.tandfonline.com