Another sally into the obscure, or, an inquiry into the origin of Rainwater Madeira, featuring notes on Madeira: Wine Cakes & Sauce by André Simon & Elizabeth Craig.

1. A strange and wondrous wine.

Rainwater Madeira is an oddity, odder still than other Madeiras. They are strange wines vinted through a strange process. Like Sherries and Ports they are fortified to preserve them by boosting their alcohol level. Like Sherries but not Ports they emerge from a solera system that takes a mother wine from stocks created long ago to ensure the consistency of their distinct character. Each year wine from the new batch tops up the solera to replace the portion that helped create it.

Vintage Madeira bottles

Unlike Sherries or Ports, Madeira endures being ‘cooked’ during the winemaking process. Casks of ‘new’ wine, recently fermented but not yet fortified, lie in estufas, or warming chambers, at temperatures ranging from 100° to 160° F. The duration of time that the wine lies in the estufa and amount of heat varies by producer and type of grape.

Producers follow three different procedures to heat the wine. The traditional, slowest and therefore most expensive method simply places wooden casks in the hot loft of a warm warehouse for as long as it takes to ‘cook’ the wine in the opinion of the vintner. The process, called ‘cantiero,’ can take decades and, in some cases, as long as a century.

A lone producer, the Madeira Wine Institute, heats wooden casks of the wine in a specially designed steam room from as little as six months to more than a year.

Most Madeira, however, gets cooked via a modern shortcut that is considerably faster, cheaper and easier to control. The new wine is heated in steel or cement tanks encased in heating coils that carry hot water. The process does not yield wines of a quality comparable to the other two. (Robinson 416-19)

The process gives all fortified Madeiras an extraordinary shelf life even after a bottle has been opened. As André Simon explains, “they will stand more rough usage and live longer than any other wine.” (Simon 24)

2. Rainwater, the strangest of them all.

The origin of the Rainwater style, its characteristics and name remain obscure. Unlike many true Madeiras, each made from a distinct varietal, Rainwater is a blend of grapes. It usually lies on the drier scale to the south of Verdelho and north beyond Sercial in sweetness.

According to Noël Cossart, “[t]he margin between a Sercial and a dry Rainwater is narrow. The former is from a particular grape and the latter a blend.” Elsewhere he asserts that “Rainwater… is a soft style of Verdelho.” (Cossart 182, 151n. 48) Berry Brothers & Rudd, the best of all wine merchants, lends support to the claim, at least in historical if not contemporary terms. They explain that Rainwater is “traditionally associated with the Verdelho grape variety.” (bbr.com)

Then again, in about 1900 Charles Bellows, variously described as “a wine scholar” and “wine and spirit merchant,” considered a wine that had been listed as Rainwater to be “Sercial and a splendid specimen.” (Cossart 182; fortheloveofport)

Nothing to do with Rainwater Madeira

Some Rainwaters, however, are the driest of all Madeiras. Alone among them, Rainwater also has a limited sphere of distribution dominated by a single national market.

3. Epistemological origins.

Usage of the term itself has evolved. The most highly prized of all Madeiras by 1900, today Rainwater may (or may not) denote “inexpensive, oversweet, acid-lacking Madeiras that don’t fit into the other categories” of wines produced on the island. The plonk passed off under the historic name may “bear little resemblance to the original Rainwater Madeiras.” (wine-searcher)

Rainwater became a catchall out of the unforeseen consequences of regulation. While strict production laws apply to the grades of Madeira named for grape varietals, the Rainwater style “remains as unconfirmed among Madeira’s winemakers as it does among the EU’s wine legislators.” (wine-searcher; but see the Notes)

The motives of producers have not always been nefarious in this respect. Over the years, a number of shippers have called Verdelho Rainwater “owing to the difficulty of pronouncing the word Verdelho.” (Cossart 151n. 48) Confusion also has arisen because many Madeiras traditionally have been named for the ships that carried the casks from the island or the magnates who purchased them in North America.

4. Disputed origins of the first ‘American’ wine.

During the eighteenth century, “American merchants [were] by far the largest purchasers of Madeira wines.” (Simon 21) Rainwater in particular was created either by or for American consumers toward the end of the century, depending on the origin myth that a given chronicler believes. It retains the association to this day and some writers even refer to it as ‘American Madeira.’ (See, e.g., Cossart 146)

Simon is unequivocal. He places the first Rainwater with a particular merchant epicure in the American south:

“Rainwater was the name given mostly in Charleston and the South to a Madeira which a Madeira enthusiast, a Mr. Habisham, of Savannah, had succeeded in making lighter in colour and body, by some secret fining method, without, so it was claimed, spoiling either flavour or bouquet.”

Simon also states that the terms ‘Rainwater’ and ‘Habisham’ interchangeably described the new style. (Simon 24)

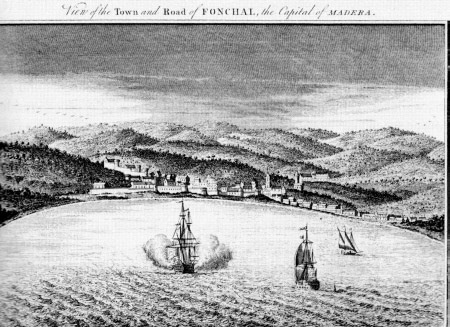

Jefferson’s Madeira decanter

Cossart defenestrates Habisham as originator of the Rainwater style. (Cossart 176) While conceding that Simon’s Mr. Habisham, actually William Neyle Habersham, “had one of the greatest palates of his day or perhaps of all time,… liked the Rainwater-type Madeiras and perfected them,” Cossart speculates that “in fact he may not have even known the name.” (Cossart 176) In any event Habersham was not born until 1817, some time after the term ‘Rainwater Madeira’ already had appeared in print.

According to Cossart, Francis and Andrew Newton coined it during the middle of the eighteenth century. Cossart does not say so, but the brothers fled England after backing the Pretender in the revolt of 1745. Andrew emigrated to Virginia and by 1748 Francis had moved to Madeira. (Hancock 121, 121 n. 38)

At some point, as Francis prepared a shipment of wine to his brother, a number of casks, or pipes, were left unbunged overnight. It rained. As a result water mixed with the wine, rendering it lighter and more refreshing, an inadvertent innovation welcomed by planters in the warm climate of the American south. (Cossart 146)

Cossart also claims that “[a]nother version of the story is attributed to President Jefferson” (Cossart 146n. 46) and unattributed rumors persist that the wine was adulterated, whether accidentally or to defraud purchasers, on the docks of Savannah.

It is hard to take these stories at face value, not least because Rainwater shares the same strength as other Madeiras, an impossibility if the wine were merely watered. Another apparent clue lies in the description Andrew provided his brother to explain the appeal of the lighter style. Cossart himself supplies the quotation: “pale soft wine…. Soft as Rain Water and the colour of rain water which has run over a straw thatched roof into a butt.” (Cossart 146) So it is quite possible that Andrew referred to rainwater only by analogy to other Madeiras, and nobody meant to infer that water actually had infiltrated the wine.

Bellows, the Edwardian wine scholar and merchant, did not mention dilution in his contemplation of Rainwater. Instead he considered the wine a result of uncommon conditions:

“I do not know what causes Madeira to be Rainwater if it ever has been scientifically explained, but it is a freak condition of wine caused by lack of colour in the grape, sudden change of temperature, starvation of the lees or other natural causes, but it is of so rare occurrence that Rainwater is highly prized as a curiosity.” (quoted in Cossart 182-83)

5. A mystery solved…

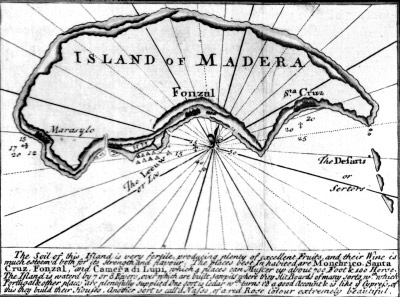

A more compelling if less colorful explanation arises from geography. The island of Madeira is mountainous; most of it is hot and dry, and most of its vineyards rely on irrigation. The slopes of the island toward its volcanic summit, however, are too steep to irrigate. In addition, average temperatures on the upper reaches of the island are some 20°F cooler than the capital on the coast, Funchal. The upper elevations often are shrouded in cloud and receive over 110 inches of rain annually, far more than the sunny lowlands. (wine-searcher)

These climatic conditions would produce grapes with less sugar from the higher, less sunny, non-irrigated vineyards watered only by rain. Wines vinted from those grapes therefore would be lighter, more acidic and therefore more refreshing than their counterparts grown below. If the vineyards at the high elevations produced the original Rainwaters, then the provenance of their name would appear obvious.

6… or maybe not.

All this begs the question how Habersham ‘perfected’ his Rainwater Madeira, whether he called it that or not. He must have been up to something, because anyone lucky enough to taste the wine remarked upon its singularity.

According to Cossart, “he had built himself a solarium over the ballroom” of his big Savannah house, “so private that it was only accessible from his dressing room.” (Cossart 176) There he stored his wine, a practice less eccentric than it sounds:

“It was in fact quite normal in the south to keep Madeira in attics rather than in cellars, just as it is in Funchal, which is precisely on the same latitude as Savannah and where all the wine is stored above ground.” (Cossart 176)

That remains the case today in southern cities like New Orleans, which anyway has extremely few buildings built over cellars due to the height of the water table.

Habershaw must have been something of a celebrity, and his house must have been considered somewhat strange, because the Atlanta Constitution reported in great depth about its characteristics. Something about his solarium was eccentric in terms of wine storage, at least outside Madeira. In contrast to a cellar, the high room was flooded with light: “On every side and on the roof is glass, admitting the rays of the sun without hindrance.” (quoted at Cossart 177) So Habershaw had constructed his own estufa, where he took the unique step of ‘cooking’ his Madeiras a second time.

Whatever its other effect on the characteristics of his Madeira, Habershaw’s supplemental cantiero could only have concentrated and possibly darkened it. The wines must have required some other treatment so they “not only became lighter in colour, but also in body yet preserving their full flavour and bouquet.” Habersham did not publicize his methodology and if he kept notes they do not survive. In 1929, Frank Gray Griswold insisted that “so-called Habersham Rainwater wines had been treated in an artificial manner by a secret method” to achieve such apparently incompatible effects. (Griswold quoted by Cossart 176)

‘Fining’ a wine to clarify and stabilize it has long been a common viticultural practice; during the nineteenth century typical fining agents included beef blood, egg whites and isinglass. Egg whites along with bentonite, a clay that absorbs proteins and other impurities that cloud wine, are among the most common fining agents used by winemakers today.

Cossart theorizes that Habershaw broke from contemporary practice to fine his wines with Louisiana clay, something he describes as “crude in comparison to bentonite” but capable of producing the light, bright characteristics of Habersham’s Madeira that amazed his contemporaries. Louisiana clay was available in the Savannah of the time and Cossart’s theory is more plausible than any other.

Notes:

-Notwithstanding the lack of EU regulation to cover Rainwater on a par with other styles of Madeira, Noël Cossart maintains that some rules do apply:

“Rainwater, which is a soft style of Verdelho, must be at least three years old and may not use the name of any grape species. A term such as medium dry may be used on the label.” (Cossart 151)

-Madeiras from the Rare Wine Company are special indeed, but expensive. The driest, ‘New Orleans Sercial,’ is hard to find but worth the effort and cost, even more than the other Rare Wine styles named for colonial North American ports.

-Thoughts on cheap fake ‘Madeiras’ appear in the practical.

Sources:

Anon., www.fortheloveofport.com/books/port-lover-s-library/ (accessed 21 May 2013)

Anon., www.wine-searcher.com/regions-madeira+-+rainwater (accessed 21 May 2013)

Noël Cossart, Madeira: The Island Vineyard (2d ed. Sonoma 2011)

Simon Field, “Berry’s Rainwater, 5-year-old,” www.bbr.com (accessed 21 May 2013)

Frank Gray Griswold, Madeira (New York 1929)

David Hancock, “‘A revolution in the trade’: wine distribution and the development of the infrastructure of the Atlantic economy, 1703-1807,” in John McCusker & Kenneth Morgan (ed.s), The Early Modern Atlantic Economy (Cambridge, England 2001)

Jancis Robinson, The Oxford Companion to Wine (Oxford 2006)

André Simon & Elizabeth Craig, Madeira: Wine, Cakes & Sauce (London 1933)