No small surprise: The unexpected utility of cheap fake Madeira.

On a rainy and cold April afternoon the Editor found herself with a companion at a favorite place, the bar of Husk in Charleston, South Carolina. Roderick Weaver, the head bartender, had opened his doors early to shelter sodden wanderers like us.

Later that evening the place would be scrummed, but it was quiet during our earlier visit. We all got to talking and the subject turned to Madeira, as it should, and to the ones sold by the Rare Wine Company. All of us consider them superb but, sighs all around, expensive, even by the relatively pricey standards of Madeira.

Weaver mixes a lot of drinks, and in keeping with the local, historicist ethos of Husk many of his cocktails derive from eighteenth century sources or get their inspiration from them. According to his barcard the ‘1793 Charleston Dragoons’ Rum Punch’ for example, relies on an eighteenth century recipe, presumably excavated by archaeology graduate students from a disused privy behind the officers’ mess. Whatever its source, the drink is the authentic evocation of a Caribbean rum punch, and that is appropriate; Charleston originally was settled via Barbados and kept its island ties into the nineteenth century.

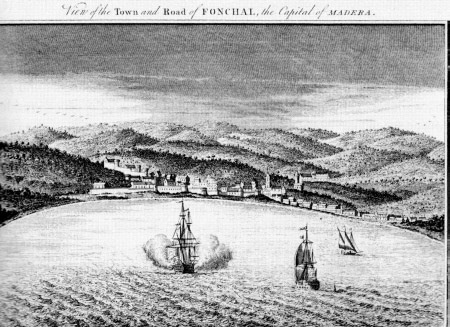

The city also, like its counterpart ports along the eastern seaboard of North America, imported a lot of Madeira during the eighteenth century. The association of wines from Madeira with the British mainland colonies was strong, stronger than with Britain itself due to various intricacies of mercantilist legislation enacted by the stewards of empire back in Westminster. For anyone who cares about the revival and reinvention of Low Country foodways, Madeira should be an irresistible ingredient and, at Husk, it is.

Keeping prices beneath the ionosphere at Husk requires imagination behind the bar as well as at the stove because Sean Brock, executive chef and landrace visionary, insists on the best ingredients. According to Weaver, they share “a commitment to purity, history, and the way things are supposed to be.” (Quoted in The Local Palate, February.March 2013)

Not that the bar at Husk is a cheap. Two drinks apiece for three of us with an order of fried pickles set us back more than $60 later in the evening, and only one of those rounds consisted of cocktails rather than beer or wine. Yet Husk represents good value; the rotating list of draft beer comes from regional craft brewers, the selection of wines by the glass is good, while Weaver and staff pour their drinks with a heavy hand.

And then, as at the restaurant across the way, there is the food. Fried, deep fried in fact, pickles may sound more appropriate to Hooters than to a restaurant that currently is among the most celebrated on the planet, but mock not. The selection of pickles was house made, the frying technique impeccable, the cornmeal coating therefore greaseless and crisp.

Husk, Charleston SC

The Editor’s companion, one of those entrepreneurial investment advisors whose machinations resemble alchemy, considered them the best dish he had sampled among a lot of memorable ones during our stay in Charleston. The dining landscape there may be overheated and overhyped at the moment, and most of the restaurants in town cannot cope with the crowds, but just as some paranoid people actually are being followed, a big proportion of the food there is memorable. Even so, the fried pickles at Husk scooped the competition and were among the most addictively intriguing things the Editor has eaten anywhere.

The Editor understands that this note is not called “A Heuristic Consideration of the Fried Pickles of Charleston, South Carolina and the Ashley and Cooper River Catchment Basins” or anything portentous like that, so back to the booze and, in fact, to Madeira. Weaver is willing to look for things in strange places, for example bulk producers of wretched wine. Not just one of them either; Weaver has experimented with the products of both Cribari and Paul Masson.

At this point it should not require much perspicacity to anticipate that these wines are cheap fake Madeiras. Unlike the ‘Ports’ and ‘Sherries’ produced in California and Australia, however, not much counterfeit plonk lurks behind labels trading on the reputation of the islands off Africa. That is because they no longer enjoy much of a reputation; sales of Madeira had slumped by the close of the nineteenth century and never again have approached their earlier heyday.

Sailing back to Husk; as noted, Weaver is nothing if not inquisitive and therefore can contemplate the unconventional. When explaining that he sometimes adds cheap fake Madeira instead of the real thing to cocktails and punch, he poured the Editor a taste of undiluted ‘Paul Masson California Madeira.’ The Editor, no snob when it comes to alcohol, would consider nearly anything short of meths, but the operative adverb here is ‘nearly’ and she never would have bought a bottle of geographically oxymoronic Madeira. Her betting had placed the odds on a level of quality at par with abominations like One Buck Chuck, Night Train Express or other Paul Masson products.

The Masson Madeira looked wrong in its glass (this being Husk even the choice of glass arose from reflection; Weaver used the proprietary one from a Scottish whisky distiller). It was pale like a Fino Sherry, not maroon like Madeira, and while the viscosity exceeded a dry Sherry its texture was not quite Madeiran either.

It tasted pretty good, and tasted better chilled when the Editor tried it a week later at home. The Masson imposter was nothing near as dry as a Fino despite the resemblance, but significantly drier than any authentic Madeira. That is no bad thing if our discussion turns to an aperitif or addition to some savory dishes. This product, as Bentham would have turned from contemplation of his panopticon to say, has utility.

The Editor was intrigued. She scouted her vinous haunts in southern Rhode Island, central Massachusetts and around New York City for other cheap fake Madeiras. The search would prove more difficult in New York than in Rhode Island, which makes some sense; the same pattern applies to finding the real thing with the exception of the Ironbound enclave in Newark. Among fortified wines, most places stock cheap fake Marsala, for cooking, and cheap fake Sherry, for elderly wino ladies, but no ‘Madeira.’ After failing to find anything at over a score of stores, the Editor uncovered only four impostors in addition to M. Masson; the Cribari that Weaver had stumbled upon, Pastene, Opici and Taylor. The first trio comes from California and the second pair from New York.

None of these wines wears labels that bear any useful description. Are they dry, off-dry, sweetish, sticky sweet? Other than Pastene, they do not say, and Pastene describes its iteration as ‘sweet,’ when in fact it is relatively dry by the standards of Madeiras both authentic and fake.

Casks of the real thing

Cribari unhelpfully explains that its Madeira consists of “slowly baked cream sherry which is then blended with Flor Sherry [sic] and sweetened with Muscat…” before it is “…blended with wine spirits.” What is the grape, or what are the grapes, that go into the ‘sherries?’ How or why does Sherry become Madeira? Is the wine spirit brandy, or something neutral; probably neutral, it is cheaper. At least we have learned that they include the decidedly inauthentic Muscat in their blend.

The other producers say even less; Masson, in crabbed prose, that Madeira (but in actuality not this domestic wine) is “famed as the favorite of Thomas Jefferson and others during the colonial times;” Opici, that its version “is produced from premium varietal grapes” and “undergoes a heating and cooling process which gives it a truly unique and distinctive flavor.”

At least Opici is more fun. They seem to think they know the customer for their Madeira, and she does not live in a luxury building at a prestigious address. Then again their advertising crew merely may have done them a disservice with some unfortunate phrasing. “Abundant in flavor,” and, they might have added in this apparent context, alcohol, they note that their Madeira “is ready to drink from the bottle.” The screwtop is handy too; breaking the neck of the bottle would not be required of anyone lacking shelter or tools.

Print may fail us but enter vision and taste. The Paul Masson, Pastene, Cribari and Opici wines fall in that order on a continuum of color and flavor ranging from drier to sweetest and, as we then should expect, paler to darkest. These wines are vinted to ape Madeira, so none of them could be characterized as bone dry although the hues of the Masson, Pastene and Cribari versions might mislead; even the relatively deeper color of the Cribari is a lot paler than true Madeira.

For our money, and a purchaser would not need much, somewhere between $5 and $8 a bottle, the Paul Masson is the best of the decent enough quartet. Its paler color and drier taste set it far enough apart from an actual Madeira to lessen any sense of loss from the missing subtlety.

Although it might be a good idea, the Editor has not forgotten the Taylor Madeira, which amounts to an outlier. It was the least like the real thing. In common with the other fakeries the Taylor product has no finesse, but unlike them it tastes like Smith Brothers cherry cough drops. It is sweeter than any of the others and left a sticky sheen on the palate, like a reduction of Coca-Cola. As much like a Port as a Madeira, but not much like either of them, Taylor is the only one of the American Madeira variations that the Editor would not buy again; not even for cooking, except, possibly, a dessert, but only in a pinch.

The producers of these products do not exhibit much pride in them; promotion and publicity are nonexistent. It also proved impossible for the Editor to determine online what grapes the vintners use to make them. Apparently a “Gibson Wine Company” produces “Cresta Bella Madeira” somewhere in California, but they seem to do their best to keep the wine a secret.

One California vineyard that makes ‘Madeira,’ however, displays no such reticence, but its wine is disqualified for our immediate purpose. The one from V. Sattui, an idiosyncratic California vineyard, is hardly cheap, even compared to actual Madeira, at something like $50 if you can find it.

According to its website, V. Sattui dates from 1885 and established its ‘Madeira’ solera over 120 years ago, making it one of the oldest in the world. The adjective bears quotations for good reason; like the Taylor product, this one does not emerge from traditional Madeiran varietals. Instead, it is “a blend of ancient port, rich Zinfandel and fine brandy” that, V. Sattui boasts, “gives it a sweet hazelnut, burnt-caramel flavor that is both intriguing and haunting.”

Their pride may be justified; we do not know, because the wine is sold only direct from the winery, but the Sattui ‘Madeira’ enjoys an ardent following online.

Before anybody rushes out to buy shares in Paul Masson, Pastene, Cribari or Opici in anticipation of the Great Boom in Cheap Fake Madeira, the Editor feels obligated to disclose a few disclaimers. People do not appreciate sweeter wines these days, or at least try to convince themselves that they do not, and anyone who dislikes good Madeira will not like the fake stuff any better. As the Editor’s friend the investment advisor warily notes, the ersatz variations are not subtle wines, and exhibit none of the complexity of most Madeira, although they do stack up pretty well against ‘Rainwater,’ a dryish blend of grapes at considerably lower cost.

Most authentic Madeiras are made from the single varietal that gives each one its name, from Sercial (driest) up the scale to Malsey (sweetest), a variation on Malvasia. The origin of both the term ‘Rainwater’ and the style itself remain obscure, along with the reason why the blended variant reaches market only in the United States. That, however, is the subject for another essay, in the lyrical.

Recipes for food and drink in which cheap fake Madeira is a suitable ingredient appear elsewhere in the practical.