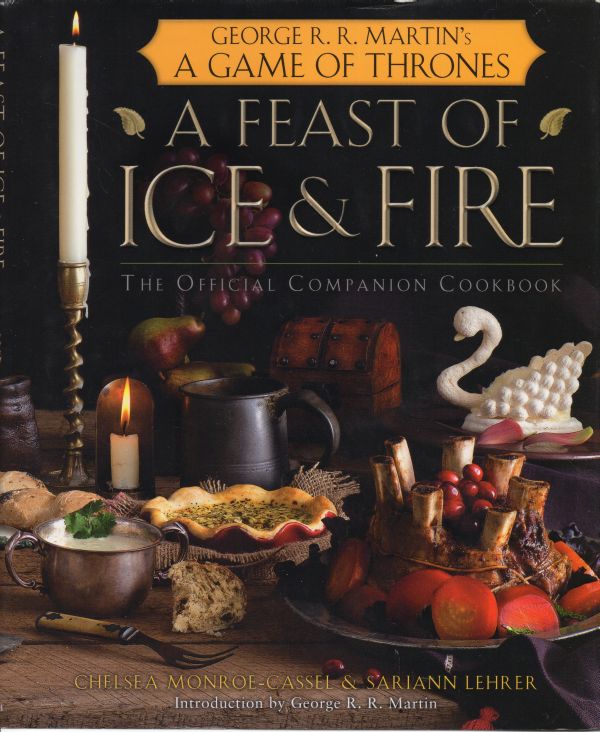

A Feast of Ice & Fire: The Official Companion Cookbook to George R. R. Martin’s A Game of Thrones by Chelsea Monroe-Cassel & Sariann Lehrer

With the imminent arrival of the fourth season of A Game of Thrones, the HBO TV series based on George R. R. Martin’s fantasy novels, I thought I would take a look at this “companion cookbook” co-written by a couple of Boston-based food bloggers. Cookbooks that seek to replicate the foodways and recipes of a fictional or historical world have become something of a meme. Thus we have a cookbook based on Downton Abbey, The Jane Austen Cookbook, The Unofficial Harry Potter Cookbook and, most strangely, not one but two cookbooks based on The Hunger Games. It is difficult to understand why no one has written The True Blood Cookbook, or potentially more interesting to followers of bfia, The Ripper Street Cookbook.

But putting aside the silliness factor, not all of these books are without merit. The authors of A Feast of Ice & Fire were inspired by Martin’s meticulous exposition of the pseudo-Medieval dishes that his characters enjoy to conduct research about early European recipes that mirror the foods described in the novels. Unfortunately much of what passes for food description in A Game of Thrones boils down to lists:

“There were great joints of aurochs roasted with leeks, venison pies chunky with carrots, bacon, and mushrooms, mutton chops sauced in honey and cloves, savory duck, peppered boar, goose, skewers of pigeon and capon, beef-and-barley stew, cold fruit soup.” (A Clash of Kings)

But the authors have worked hard to find recipes, many from early English sources, that might be served together and include ingredients that make sense given the climates of the fictional regions.

The book’s format starts with an original recipe, often Medieval but always old, with substitute ingredients which either are no longer available or have more accessible modern equivalents that do not alter the flavor. This is followed by a modern version of the recipe, which tends to reduce or eliminate the stranger spicing found in the early recipes and introduce additional ingredients more recognizable to the modern palate.

A good example is the entry for Pease Porridge from “The Wall” section of the book:

“They ate oaten porridge in the mornings, pease porridge in the afternoons, and salt beef, salt cod, and salt mutton at night, and washed it down with ale.” (A Feast for Crows)

This quotation (another list) from the novel is followed by a recipe literally transcribed from The Forme of Cury, a fourteenth century cookbook often described as the first printed in English. It is pretty indecipherable--“Take and seep white peson and oute p perrey”--but the authors provide instructions in modern English, including cooking times and measurements, to make the porridge in a Medieval manner “characterized by a surprisingly sophisticated undercurrent of herbs and spices.” A number of recipes for these spice combinations appear at the front of the book including poudre douce, which would have been essential to a Medieval cook’s larder but have since disappeared.

Moving on to the modern Pease Porridge, the authors (or at least Ms. Lehrer, who, according to her biographical sketch is “something of a British cultural history enthusiast”) demonstrate an appreciation for current British cooking.

“This modern version is more subdued than the medieval recipe. It is best served warm and goes well with meats, cheeses, and other light lunch foods. Pease porridge is a traditional British side dish, and is still prepared today in one of two ways. The peas can be boiled in a pudding cloth, resulting in a moister and softer porridge, or baked in the oven. The baked peas will be dryer, with delicious crispy bits on the top and around the edges.” (Feast)

There are many interesting recipes with British roots throughout the book, especially in the sections for “The North”, “The South”, “King’s Landing” and “The Wall”. They include pies of pork and beef (with an innovative bacon lattice crust), mutton in onion-ale broth, and a number of lovely sweets like applecakes and Elizabethan buns with raisins, pine nuts and apple. The recipe for Aurochs with Roasted Leek comes with the helpful suggestion to substitute beef or bison for the long extinct aurochs. I kind of knew I would not find any aurochs at the Stop & Shop, but I probably won’t find bison either.

The sections on “Dorne” and “Across the Narrow Sea” veer toward the Mediterranean and Arabic world, and even include a recipe for “Honey Spiced Locusts” (substituting freeze-dried crickets), a nod to the enthusiasm for sustainable home farming currently in vogue. I have not tried that one but, if you choose to give it a shot, there is an incubator for breeding grasshoppers at home called “Lepsis” which recently won Mansour Ourasanah, a Chicago industrial designer, the $35,000 Vilcek Prize for Creative Promise. It looks something like a DNA helix dropped inside an electrified salad spinner and should activate the libido of crickets too.

A love nest

To return to the seven kingdoms, this surprisingly useful cookbook is a lot of fun for fans of the books, the HBO series and indeed anyone interested in food history.

-Stephanie Dearmont