A note on Sandra Sherman’s Fresh From the Past, eighteenth century abundance, including further thoughts on pudding & Jeri Quinzio’s Pudding.

1. Enlightened British food in eighteenth century America.

Readers who take issue with the Editor’s emphasis on the continuity of British foodways in America might consider Sandra Sherman. She is a professor of literature and history at the University of Arkansas who has written on Defoe, poverty in eighteenth century London and the (British) origin of the modern cookbook. To complete this circle, she also has herself written a cookbook, Fresh From the Past: recipes and revelations from Moll Flanders’ kitchen.

There is not much of Moll in Fresh From the Past, but even so the conceit is welcome and useful. Our resourceful eighteenth century heroine lived in America as well as Britain, and in every stratum of society. Sherman has taken those ‘facts’ as the springboard for a synthetic study of the evolving cuisine that the two interlinked Enlightenment cultures shared.

She considers the food of ‘the long eighteenth century,’ which she dates to the 1660 restoration of Charles II, “a real surprise” in two ways. While the food, its flavors and textures now are unknown to most people,

“this food was America’s food: settlers in the new colonies imported British seeds, raised animals from British stock, and cooked from British recipes. In a sense, ‘authentic’ American cuisine--the cuisine that we started with--is British, reflecting what the colonists knew, liked and sought to recreate.” The irony of the ‘exotic’ cuisine that we offer” in Fresh From the Past “is that it’s as American as apple pie--which in turn is British.” (Fresh 1)

2. A phrenzy for culinary Improvement and experiment.

The long eighteenth century, which ended at Waterloo in 1815, was a serendipitous time for culinary transplantation. Britain, Sherman says, “exploded with culinary potential.” It was an age of inquiry and improvement, in agriculture, husbandry and a burgeoning array of processed foodstuffs.

Even in the center of London, enterprising farmers harvested a variety of foods. Orchards and dairying dotted the landscape of Highgate and Hampstead to supply the city’s expanding population. (Inglis 318) At Vauxhall, growers raised foods nobody now considers British, produce like apricots and melons in special ‘pits,’ pineapples and sprouting purple broccoli. Hothouses harbored pineapples too, along with every imaginable citrus, which also traveled well enough for importation. (Inglis 151)

The intersection of Enlightenment and Empire transformed the culinary culture of colonial as well as metropolitan Britain. As Sherman explains, legions of inquisitive cooks gained access for the first time to “ ….varieties of East and West Indian pepper, cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves in abundance.” Cayenne, it has been remarked, was the pungent taste of empire. “There was chocolate, vanilla, and an increase in available sugar. Cooks experimented with this variety, creating new dishes, enhancing old ones… and writing cookbooks.” (Fresh 2; second set of ellipses in original)

The Age of Enlightenment “was bursting with culinary texts--men’s and women’s, classy, classic, and funky; urban and rural, Scots and English.” (Fresh 2) The reading public devoured them. The Art of Cookery Made Plain & Easy by Hannah Glasse went through countless editions and, other than erotica and the Bible (evergreens to this day), became the bestselling text of the eighteenth century on any subject.

In an age obsessed with reputation and stature, food was a potent means of cementing social eminence. It was fashion, then as now. Host and hostess alike vied to impress their guests with culinary fireworks. The mania was by no means confined to the domestic sphere, at least not in the capital.

3. The primacy of London.

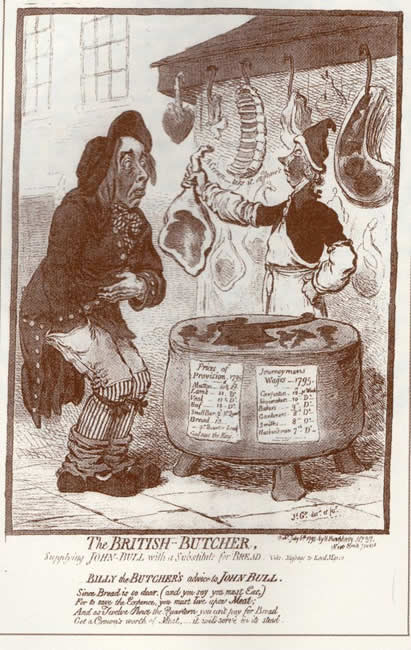

London might justifiably lay claim to the title culinary capital of Europe; continental tourists headed to the city for the specific purpose of visiting John Farley’s London Tavern, and it was not alone.

“By late Georgian times, London was a siren of steaks, chops, sausages, veal, hams, tongues, cutlets, kidneys, ragouts and meat pies. The Epicure’s Almanack (1815) reports that the ‘raised pie of huge dimensions’ at Mr. Smith’s Eating House is ‘built with alternate layers of ham and veal, the interstices filled with a highly flavored, well-seasoned transparent jelly.’ Who could resist?... Food was constantly available, constantly on exhibit.”

Sherman seems surprised that even “Parliament itself sometimes smelled like an eating house, and its private dining room was famous for its steaks, chops and veal pies” (Fresh 57) but the Palace of Westminster still smells that way and its dining rooms retain their fame.

4. We did not get here first.

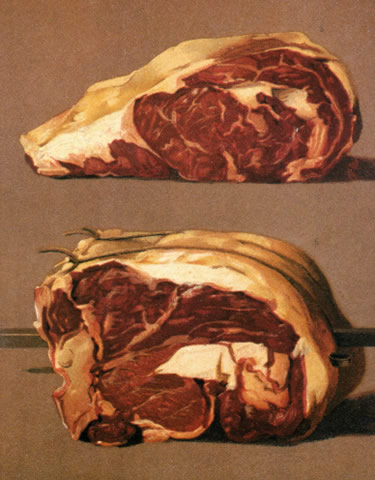

We should be rash to underestimate the expertise of these people from the past. The hipsterized denizens of Portlandia and Brooklyn have tumbled to the notion that the treatment of animals matters, in terms of ethics as well as taste, something that the industrial producers and supermajority of consumers had ignored across the length of the twentieth century. Not so our Enlightened forebears. As Sherman notes, they knew better:

“Because meat was not packaged, and was cut off a haunch at the customer’s request, it was possible to imagine it as it was on the hoof, eating and running around. How animals were raised--their food and conditions--was a lively topic in cookbooks, since care affected quality.” (Fresh 57)

Sherman contends that all these books, all this food and spice, “animate Anglo-American cuisine as legacies of Britain’s empire. Cooks experimented with these foods, and wrote cookbooks for an imperial power that cooked from scratch every day.” (Fresh 2)

This last point merits attention in an era when the percentage of any population in the western world that ever cooks from scratch begins to approach absolute zero. Our culinary skills erode faster than our attention spans in this era of instant--but fleeting--gratification. And yet the worriers among us might take solace from the theory that no number can quite reach the absolute void. If mathematics governs foodways, the currency of cooking skills should not plummet to extinction, but perhaps we digress.

The point about the decline in cooking merits attention, not, at least not now, for advocating a return to the stove, but rather because those without kitchen skills tend to assume that nobody else has had them either. The misperception may be fueled by the numbing variety of readymade tomato sauces, ‘hamburger helpers’ and other shortcuts from the chemical laboratory that line the shelves of any supermarket.

This fall of the cook and rise of convenience distort our perception of what people in the ‘primitive’ past might have eaten. As Lucy Inglis notes in Georgian London, “[m]any labour under the misapprehension that Londoners of the past ate nothing but meat, with no fresh vegetables, or they ate no meat at all and lived upon bread and cheese.” (Inglis 151) That is anachronistic.

“Salads and tomatoes seem to have been universal. In the cooler seasons Londoners resorted to cooked vegetables, and Frenchman Henri Misson de Valberg remembered his roast beef ‘besiege[d] with five or six Heaps of Cabbage, Carrots, Turnips, or some other herbs or Roots, well pepper’d and salted and swimming in Butter.’” (Inglis 151-52)

Out in the country, Parson Woodforde cultivated artichokes, cauliflower and cucumbers. He brewed beer and raised pigs. His confluence of enterprise caused a certain inconvenience because the inquisitive animals appreciated the brewer’s art:

“Brewed a vessel of strong beer today. My two large pigs, by drinking some beer grounds out of one of my barrels today, got so amazingly drunk by it, that they were not able to stand and appeared like dead things almost…. I never saw pigs so drunk in my life…. ” (Grigson 43-44, quoting Woodforde)

The effect of the binge lasted into the following day when, Woodforde noted, the inebriates “tumble about the yard and can by no means stand at all steady yet.” (Grigson 44, quoting Woodforde)

5. Globalization of the locavores by revolutionary means.

Turning from the liquid back to the solid, an astounding variety of affordable foodstuffs became available in Britain during this preindustrial age. Its merchant fleets had been importing great quantities of goods for decades before the long eighteenth century. To list but a celebrated few, anchovies, capers and Parmesan, along with wines from all over Europe, were prominent fixtures in the British larder and cellar.

Then as now, London dominated the global wine trade, while warehouses in Leith, the port of Edinburgh, held some of the biggest stocks of Bordeaux on the planet. Caribbean production on an industrial scale brought bigger and cheaper shipments of sugar as the century progressed, but the shipment of staples was by no means confined to the sealanes.

The long eighteenth century stoked financial, commercial and transportation revolutions in Britain hardly less transformative than their industrial successor.

At this juncture, as at others, Sherman loses her way. Her claim that “Britain’s varied terrain and poor roads” explain “the astonishing regionality of eighteenth-century British food” is a recitation of received wisdom, not an indication of historical acuity. (Fresh 18)

Regional foodways in Britain survived the railway boom too, and as Tim Blanning demonstrates in his magnificent Pursuit of Glory, although the roads of Europe had endured neglect since Roman rule, they were overhauled on a grand scale during the eighteenth century. Acts of Parliament financed a system of turnpikes that, coincidentally, created the romance of the highwayman. The confluence of cash required to raise the tollgate and wealthy travelers made for easy pickings and a kind of economy of larcenous scale.

Travel times decreased at what seemed an astonishing clip. A newspaper advertiser in 1754 found it prudent to explain that “[h]owever incredible this may appear, this coach will actually arrive in London four days after leaving Manchester.” In 1700 it took 90 hours on average to travel between the two cities; by 1750 the trip took 65 hours and, by 1800, 33.

The construction of an efficient road network during the eighteenth century did more than spur the creation of a rapid post, the epistolary novel and highwaymen. It not only allowed people to traverse the country in record time, but in conjunction with an emergent system of canals also mobilized the market in any number of goods, including food. During the 1740s, English roads could support wagons carrying at most three tons; by 1765, sturdier roads could take improved wagons drawn by the same number of horses to haul six tons.

Enterprising entrepreneurs cashed in. The increase in efficiency lowered the price of food from relatively afar and facilitated the trade in perishables. Fresh fish found their way inland for the first time, some carried live in tanks designed for the purpose.

6. Preservation in coexistence with innovation.

As Sherman reminds her readers, the innovations of the age did not include refrigeration. Particularly in the winter months, the population relied in great degree on foods preserved by drying, pickling, salting and smoking, singly or in combination. Cookbook authors therefore took pains to find an innovative formula for the best bacon, brawn, blood puddings, potted meats, pickled tongue, sausage or spiced beef.

Sherman thinks the British cookbooks of the eighteenth century reflect that reality because their recipes for preparing preserved foods predominate. It is a dubious proposition. In any age a cookbook will recommend a single way to roast beef or boil chicken; processed foods did, and do, require more technique for transformation. Eighteenth century English diners had cultivated a craving for complex, robust flavors, as their mania for spice attests, and all those recipes may simply reflect that fact.

7. Historical infelicities and culinary omission.

Elsewhere Sherman recycles the unsubstantiated myth that British sailors carved their petrified stores of meat into sculpture; as N.A.M. Rodger has demonstrated, and the Editor’s essay “Food at Sea in the Age of Fighting Sail” reminds our readers, the Royal Navy took pains to procure the finest victuals for the fleet at considerable cost, and tars typically enjoyed a better diet than their social equals ashore.

The essay on pudding in Fresh from the Past does not appear until the eighth chapter and looks like an afterthought. That is more than passing strange in a book devoted to the cooking of eighteenth century Britain, because its puddings were ubiquitous and repeatedly remarked upon as such by contemporaries.

Like an American League pitcher in a National league ballpark, Sherman takes a feeble wave at her target. She lists the usual suspects on pudding--Barlow, Misson, Rumford--and adds a dissonant reference to Jefferson. After citing Barlow’s “Hasty Pudding: A Poem in Three Cantos,” Sherman confides that “[t]here is no record of whether Thomas Jefferson, a francophile gourmet, hailed Barlow as a hero.” (Fresh 210)

There is no record whether Vladimir Putin has hailed Barlow for his paean to pudding either, but the odds are equally long.

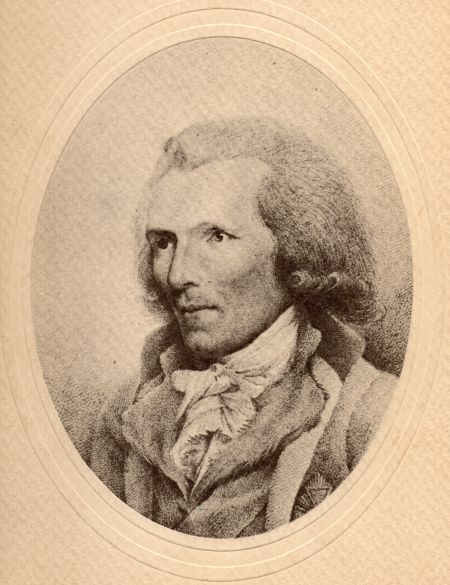

8. Wrong on Rumford.

Her treatment of Rumford is just wrong, as bad as Jeri Quinzio’s. After noting that Rumford recommended hasty pudding to the poor (fair enough), Sherman claims that his advocacy “delivers a crushing blow to the grandeur of pudding” even though his recipe “is not so different from Barlow’s.” It lacks his “sunny spirit” and “insults the poor” who “predictably… ignored it.” The campaign for hasty pudding therefore “was Rumford’s undoing.” (Fresh 211, 212)

In case our readers find the previous narrative disquieting, it is as risible as it appears. Rumford was an amoral, autocratic and humanitarian genius, one of the most complicated and contradictory figures of the age. He did not insult the poor but rather insulted everybody; if the Enlightenment had identified Tourette’s syndrome, Rumford would have been diagnosed.

The pudding recipe delivered no crushing blow. As Sherman contradicts herself in saying, nobody took much notice of Rumford’s recipe and British kitchens kept pumping out puddings in every other guise for over another century following its publication.

Nor did it prove Rumford’s undoing. He would go on to proverbial fame and fortune, publishing pathmark studies about the nature of heat, improving the comfort of housing worldwide through the invention of his efficient fireplace, serving as de facto dictator of the Bavarian principality, transforming poor relief in both continental Europe and the British Isles and much else.

He also spied against his American countrymen for the British, spied against them and the French, slept with anyone of either sex who might advance his ambitions and alienated just about anyone he ever met. Sherman’s thumbnail of him gives no perspective on the man himself.

If, however, she is not the most rigorous historian, Sherman knows how to craft a cookbook. Her format for the historicist Fresh From the Past is, ironically enough, the same as the fantasy-fueled Game of Thrones Cookbook. She pairs a quotation from the original source with her modernized version on the facing page, and it is a lovely transposition. The selection of recipes is varied and good, the omissions other than pudding inoffensive.

Our appraisal of Benjamin Thompson, Reichsgraf von Rumford, appears in the lyrical; recipes derived from Sherman’s cookbook appear in the practical.