A tale of two critiques: Our Rural Correspondent considers Tender by Nigel Slater.

Nigel Slater has worked in kitchens but does not operate a restaurant and describes himself as a home cook rather than chef. He is a prolific writer on food and has had a column in the Observer magazinesince 1993. Slater also has written for many other publications and produced ten books. His acclaimed memoir, Toast: The Story of a Boy’s Hunger, has won several awards, including ‘British Biography of the Year’. It has been filmed, with Helena Bonham-Carter in a lead role, and read on BBC Radio 4. Slater is a regular presence on television, most recently with Simple Cooking (2009) and Simple Suppers (2010-11) for the BBC. His uncomplicated approach to cooking has won him a host of admirers.

Tender, now available in paperback, fills two chunky volumes running to a combined 1226 pages. Volume I, A Cook and his Vegetable Patch, recounts the pleasures (home-grown, fresh, organic produce) and pitfalls (urban foxes, slugs and backbreaking labour) of city gardening. After a brief introduction on the origins of his interest in vegetables and establishment of his garden, Slater runs through the alphabet of common and not-so-common vegetables suitable for a cool, temperate climate.

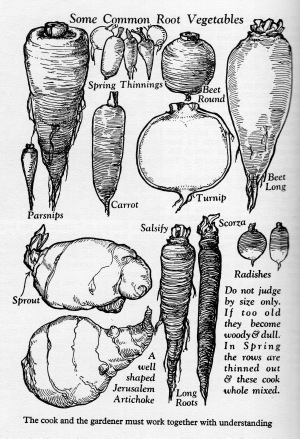

These range from asparagus (even though, in this reviewer’s opinion, it requires too much space for the small garden) and aubergines (or eggplant; not really suited to the UK except under glass) to tomatoes (not a vegetable but a fruit and, anyway, unreliable outdoors in a normal British summer) and turnips. He finishes with a short section on “a few other good things”, namely, globe artichokes, cucumber, radishes, spring onions and fennel. Most chapters include sections on seed selection, methods of cultivation, seasonings and other kitchen suggestions. Every chapter ends with recipes.

Slater has grown vegetables since boyhood, starting with watercress on wet blotting paper. As a student he grew his own tomatoes. Though not a vegetarian, he has become increasingly interested in vegetable cookery; partly out of guilt and environmental concern; partly for reasons of taste; and partly from a desire to source locally, growing his own where possible. He now allocates “veggies… the starring role” in his kitchen; meat and fish have been relegated to the supporting cast. When, on the eve of the millennium, Slater moved to a terraced house with a walled garden in North London, he took the decision to dig up a scrubby lawn and replace it with a vegetable patch. The garden is too small for self-sufficiency, but large enough to fulfil Slater’s urge to grow and supplement the offerings of local street and farmers’ markets.

There is much to admire in Slater’s writing, the culinary advice he dispenses and the recipes he provides. Has anyone ever described a simple baked potato more seductively?

“A baked potato can be a perfect thing, brought rough-skinned from the oven between warm oven mitts, its crust sparkling with salt like a pearlescent frost, its interior the texture of deep snow.” (Slater 465)

Whether serious vegetable growers or even ‘townies’ with small gardens will turn first to Tender for growing advice is another matter. By his own admission, Slater has never grown asparagus, celery or even the prosaic parsnip and some of his gardening notions are eccentric. For example, he appears to grow potatoes in profusion (seemingly as many as five different varieties) yet the ‘spud’ is a vegetable that gardeners pressed for space should eschew. Not only do potatoes take up considerable room but, with the exception of early varieties, home grown crops have no special advantage in terms of flavour. There are even stronger reasons to avoid spring broccoli, whether purple or white sprouting, another vegetable Slater recommends. Although freshly picked broccoli does taste wonderful, a parent plant demands even more space than the potato. Furthermore, unlike potatoes, which can reach maturity in three to four months, broccoli plants take almost a year to crop.

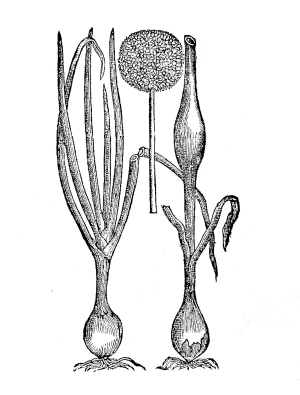

Strangely, Slater ignores garlic notwithstanding its importance in the kitchen and the fact that its growing season of September to June occupies a period when little else competes for space in the vegetable patch. Even odder, Slater wonders why any amateur gardener with limited space would bother with onions. (Slater 346) Based on more than 30 years of growing vegetables for home consumption, your reviewer regards onions as the key crop for the domestic grower. They are essential because they provide the basis for a vast range of dishes; are easy to grow, especially from sets; have few pests and actually deter some unwanted ‘critturs’; occupy little space; are quick to reach maturity; and can be stored for up to six months.

If Slater fails entirely to convince as a gardener, he is more persuasive in the kitchen and offers numerous tempting recipes. Many of these (for example, carrot and coriander fritters, potato cakes with chard and Taleggio, a meat-free pasty, cabbage and cheese gratin) will suit vegetarians--to whom Tender will be of much interest. Meat is not ignored: Oxtail and onion stew, a remoulade of celeriac and smoked bacon, and many others are alluring. But some chapters feature no meat recipes and it is fair to say that dedicated carnivores are not Slater’s target audience with this publication.

“And then there was fruit”, as Slater begins his second volume. Fruit, which affords Slater greater “joy” than vegetables, encompasses everything from apples to white currants by way of hazelnuts and, though it is not a fruit but a vegetable, rhubarb. The format is broadly the same as in the vegetable volume, that is, after a brief introduction, a chapter on each fruit focussing on its place in the garden and the kitchen, varieties, appropriate accompaniments, tips (gardening, culinary and miscellaneous) and, finally, the recipes. There is much reminiscence on the way, much of it about Slater’s childhood in Worcestershire and Birmingham.

Many of the recipes are for cakes and desserts but fruit as an accompaniment to savoury dishes is by no means overlooked. He features roast partridge, juniper and pears; lamb with quinces; roast leg of pork with spiced rhubarb; roast duck with damson ginger sauce--and much more. A great deal of practical advice and inspiration are engagingly dispensed. Two small reservations; first, such weighty tomes are not the easiest to use either in the kitchen or the garden; second, none of Jonathan Lovekin’s splendid illustrations carries a caption.

Finally, one thing intrigues your reviewer. Slater insists, more than once, that he has a tiny garden that is insufficient for self-sufficiency. At one point he describes it as twelve meters in length; elsewhere it is a “fifty-metre patch”: Is this so very small? Vegetables occupy “the heart and soul” of the garden (Slater 628). Yet the range of produce he manages to grow is staggering. Leaving aside all those potatoes and broccoli plants, he refers to five plum, three apple and two hazelnut trees. There are also damson, elder, quince and the mysterious medlar trees (one of each), plus assorted loganberries, grapes, red currants, rhubarb, figs, raspberries and strawberries. How he manages to accommodate such an array of food plants, let alone dispose of the produce, is never satisfactorily explained.

Take Slater on gardening with more than a grain of that pearlescent salt, but do lug a volume into the kitchen to cook; my own experience in baking a savoury carrot cake and following other recipes from Taste has been nothing less than salutary.

Source:

Nigel Slater, Tender (London 2011; 2 vols.)