Further thoughts on sea pie in North America provoked by the Editor’s glance through an exemplary little Canadian cookbook.

In Number 20, we discussed the origin and evolution of sea pie with an allusion to the Canadian branch of the culinary family. Further notes, some more recipes and a correction appear in order as we celebrate the foodways of Atlantic Canada.

1. We blew it.

First the correction. In reliance on The Concise New Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English, we noted in Number 20 that the term cipaille, the Francophone phonetic equivalent of sea pie, first appeared in print in 1998. Our reliance was foolhardy. Instructions for “Cipaille (Sea Pie)” appear, in French, in a predominantly Anglophone and entirely enchanting compilation of recipes from the Gaspé peninsula called The Black Whale Cook Book by a Mrs. Ethel Renouf. It appeared in 1948, a full five decades before the New Partridge Dictionary dates the origin of the term.

2. Some people we wish we could have met.

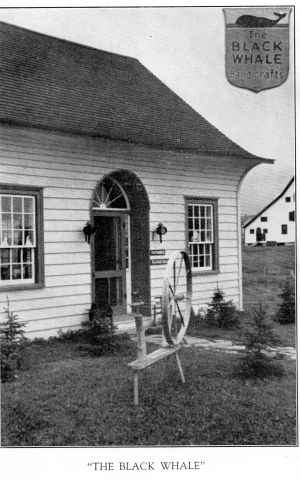

The Black Whale Cook Book is named not for a cetacean but instead for what must have been a wonderful exercise in historic preservation and revival in the little town of Perce. There, a number of thoughtful people had become concerned about the erosion of traditional material culture:

“As in many other places, the old arts were dying out. Not so noticeable during the restless speed of the summer months, the loss of these left a dreary blank through the long days of winter. It seemed inevitable that future generations would be the poorer. To prevent this something would have to be done. A local committee was gathered and the work of rescue begun…. Lectures, competitions, and exhibitions were organized, until the seed, carefully watered, had struck deep enough roots to grow by itself. Looms, spinning-wheels, rug-frames and carving tools were put into use again, and old skills revived.” (Black Whale 3)

Theirs is a worthy manifesto, and pretty good prose too.

These industrious people produced enough quilts, rugs and ship models with the help of a group called the ‘Canadian Handicrafts Guild’ to open a shop that they named the Black Whale. The goods must have been good, because the shop expanded and generated sufficient profit to fund both a dental clinic in town and “a most needed chain of Dental Caravans” for its remoter environs. (Black Whale 3)

These Whalers surpassed their helpers in pushing past craftwork. They saw their remit as historical, and became compilers and catalogers too. In 1937, the Black Whale published a book by a professor from McGill University on birds in Perce, followed of course eleven years on by the Cook Book. The publications reflect the group’s “policy of gathering and preserving the rich lore of the district;--this time the cherished recipes handed down from mother to daughter, often through many generations.” To the people of the whale, the endeavor was central to their aims, because in their judgment “cookery ranks as, probably, the oldest craft of all.” (Black Whale 3) The Cook Book gives credit to over eighty contributors, including two restaurants, Mrs. Renouf herself and the enigmatic “Irish Town.”

3. More on cipaille…

Those generations of Gaspé mothers and daughters practiced the craft with aplomb based on their recipes. Before turning to them, however, cipaille merits a little more discussion, if only to dispel a number of misperceptions. The Editor keeps finding additional assertions that sea pie contains fish, with or without meat, in both the earliest versions and Quebec variations. None of these writers cite any source; presumably the ‘sea’ in the name of the pie induced writers to assume that the word was a reference to seafood. But at least in Britain something called sea pie before the Second World War would have been most unlikely to include fish.

In 1935, A. C. Baugh and Thomas Cable asserted in The History of the English Language that the term ‘seafood’ was unknown, even “positively incomprehensible,” in England as a description of edible creatures from the ocean, and according to The Diner’s Dictionary it “does not seem to have become completely naturalized in British English until well after the Second World War.” (Ayto 315)

As britishfoodinamerica noted in Number 20, some Quebecoise have argued that cipaille emerged fully formed from the pots of Habitants, if not even earlier from those of trappeurs, before the cataclysm of 1763. These speculations informed a lively if inconclusive and friendly exchange in Tom Jaine’s indispensable Petits Propos Culinaires during 1991. We should note that the lack of resolution reflects the integrity of the correspondents rather than any dearth of skill. One of them, Gary Gillman, makes a forthright request for someone to provide “the true English or French antecedent to this Quebec specialty” that he notes is “variously called cipaille, six-pates, ci-pate, cinque pates and sixpates.” (Gillman 66, 67)

Two readers of PPC did respond to his query, although they found less reference to sea pie than the Editor did in bfia Number 20. Karen Hess finds no early reference to cipaille per se. As to ‘sea pie,’ she cites the 1755 edition of Mrs. Glasse and the American Mary Randolph from 1824 but neither Amelia Simmons (1796) nor Captain Crawford of the Regency Royal Navy. (see bfia No. 20, “Sea pie”) Hess figures that both sea pie and another “sea dish,” chowder, reached North America “by way of the English” but hedges her bet: “the idea of parallel English and French versions having come to Quebec is not to be absolutely ruled out.” (Hess 66)

Jennifer Stead tentatively states that “sea pie seems to be shipboard food” but her citations from both land and sea are more than a little puzzling and date from the late nineteenth century at the earliest. (Stead 66-67)

Elizabeth Driver also sent a response, but neither she nor the others mention The Black Whale Cook Book, which must be an oversight because Driver describes it in her extensive not to say exhausting survey of Canadian cookbooks.

The problem with all of this is the absence of any written evidence that cipaille has a Francophone origin, although, as Marc Lafrance and Yvon Desloges explain, cooking manuscripts “are practically non-existent in Quebec insofar as the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries are concerned.” (History 3) Nothing like sea pie, cipaille “or any recognizable variant,” however, appears anywhere in the vast culinary literature of metropolitan France. (Gillman 67) Nor, unlike the Royal Navy sources, has the Editor found reference to something like a sea pie (or a pudding for that matter) in any French naval record from the age of sail. These facts contrast with the many print and manuscript references, in English from both Britain and North America, to sea pie at least as early as the eighteenth century.

More generally, as Lafrance and Desloges also note, “[t]he English, whether it be true or false, claim to have invented the pie more than six hundred years ago. In any case, pies and tarts are fundamental to English cuisine.” (History 79) That is just not the case when it comes to France, which has virtually no tradition of the savory pie.

Another factor, admittedly further afield, also supports the conclusion that the antecedent of cipaille is English rather than Quebecoise or French. The absence of early Canadian kitchen manuscripts has a certain parallel. In comparison to British North America, the range of foods cooked by colonists in New France was limited.

Lafrance and Desloges maintain that oysters were a rarity in Quebec under French rule, but after the ‘Conquest’ the province was, like the entire seaboard south to the Carolinas, awash in them. (History 79) Perhaps even more of a surprise, not a single pork butcher or sausagemaker appeared “[u]nder the French regime in Canada” and in contrast to the English of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries “the French did not often eat prepared meats.” (History 45)

Perhaps this relative dearth of culinary diversity explains what Gillman, citing Lafrance and Desloges, calls the ‘surprising’ fact that in what had been French Canada “the influence of English and American writers and practices was very strong after the Conquest in 1763.” (Gillman PPC “Book Reviews” 61) That ‘strong influence’ provides another strong inference that cipaille descends from sea pie. Furthermore, it is hard not to notice in our immediate context that, while The Black Whale Cook Book includes a chapter on “FAMOUS OLD FRENCH CANADIAN RECIPES in the original French,” cipaille does not appear there, but rather shows up in the same section as English stalwarts like bubble and squeak, curry, potted meat, Yorkshire pork pie (with sage and apples) and boiled turkey.

Finally there is logic. In common with a number of French Canadian culinary terms (fricot, pot en pot, poutine rapee), cipaille does not exist in the metropolitan French language. Those other terms modify French words to alter their meanings, but cipaille does not. It is strictly the exact phonetic equivalent of sea pie. Perhaps the obvious ought to outweigh all else.

Nonetheless the Parti Quebecoise and other provincial chauvinists (double meaning intentional) can take solace, even derive satisfaction, from the inescapable notion that derivative Canadian cooks have taken an English dish and made it something grand.

On a slightly discordant note, not every author considers cipaille central to the heritage of Quebec. Neither Jehane Benoit in La Cuisine canadienne nor Marielle Cormier-Boudreau and Melvin Gallant in A Taste of Acadie (“a culinary tour of Acadie… from the Gaspé Peninsula to Cape Breton” and beyond) mention the dish.

4… and back to the Whale.

Neither of these more recent books is nearly as good as The Black Whale Cook Book. Nor is any other publication that covers the cooking of Gaspe. Elizabeth Driver describes the Cook Book as “remarkable for the detail it provides on local lore, customs associated with specific celebrations such as weddings or New Year, and the region’s traditional foodways.” (Driver 271) The remarkable little volume remained in print until 1962: It is more than passing strange that virtually nobody else refers to the book, which remains so obscure, and undervalued, that you can find it online for as little as $4.98.

A reference does appear in Julian Armstrong’s Taste of Quebec, but only briefly and to summarize a recipe for salt cod fritters which, as the assiduous reader of britishfoodinamerica will recall, also are found throughout both the Caribbean and coastal New England. Her book is good, although the index is terrible, and incidentally notes that “British cooking is part of the culinary mix in the Gaspé…. ” (Armstrong 183)

The Black Whale Cook Book is, however, of more than historical interest to the Editor, and for recipes past cipaille, although the Whalers’ version (submitted by the exquisitely named Mrs. Agnes Fennel, which makes its French usage seem a little incongruous) is a good one, and relatively simple to boot.

Those recipes are robust rather than stodgy, which befits the rugged region where they traditionally were cooked. The Gaspé juts through the galeswept Gulf of St. Lawrence at some 47 degrees of latitude, a terroir of great climactic extremes and not least of cold winters. There is much of Britain here, but also much that is distinctively Canadian; braised moose, ‘super cod tongues’ or maple syrup pie anyone?

A recipe for “cured beef ham” owes more than a little to the spiced beef that once was traditional in England at Christmastime (two versions appear in our recipes) and the bread sauce that the Whalers like with their partridge is unknown in France. Parkins, a dense dessert cake of spiced oatmeal and molasses, sounds, looks and tastes a lot like ‘Thick Perkins’ from the North of England; cretons could be haslet by another name; “an old fashioned fish pie” is the English classic topped with mashed potatoes and molten cheese; and it is hard to imagine a plum pudding or pork fruit cake (“an old time Gaspé recipe, very very good… ”) for the holidays emanating from France. We could go on.

Even if you never cook, try to find a copy of The Black Whale Cook Book. The interspersed essays on everything from “The Butcher’s Dog” to “Deep Sea Fishing” and “The Iron Pot” are as brisk and lively as the little manifesto in the preface. Besides, at a price point south of five bucks you have (almost) nothing to lose.

Notes:

- The New, as opposed to original, Partridge Dictionary covers words created beginning in 1946. The ‘old’ Partridge sweeps within its scope all that passed before.

- Despite its reference exclusively to “mothers’ and daughters” recipes, Phillip Banister, William Duval and Oliver Medsger each snuck one into The Black Whale Cook Book, as well as a captain and an Henri Labrie, whose instructions for smoking 100 pounds of salmon with brown sugar and bay (page 19) sound sensational. Among other things you will need “a barrel or a large vat” and should suspend each fish by its tail over “a very thick smoke.” M. Labie can write; his detailed description is engaging and informative.

Sources:

Julian Armstrong, A Taste of Quebec (New York 2001)

John Ayto, The Diner’s Dictionary: Food and Drink from A to Z (Oxford 1993)

Jehane Benoit, La Cuisine canadienne (Montreal 1979)

Marielle Cormier-Boudreau & Melvin Gallant, A Taste of Acadie (Fredericton, New Brunswick 1991)

Tom Dalzell & Terry Victor, The Concise New Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English (London 2007)

Elizabeth Driver, Culinary Landmarks: A Bibliography of Canadian Cookbooks, 1825-1949 (Toronto 2008)

Gary M. Gillman, “Les Cretons and La Cipaille,” Petits Propos Culinaires 37 (May 1991) ‘Notes and Queries’ 65-67

“La Cipaille/Sea Pie,” and ‘Book Review,’ Petits Propos Culinaires 38 (August 1991), 61, ‘Notes and Queries’ 65

Karen Hess, “La Cipaille and Sea Pie,” Petits Propos Culinaires 38 (August 1991) ‘Notes and Queries’ 65-66

Marc Lafrance & Yvon Desloges, A Taste of History: The Origins of Quebec’s Gastronomy (Westmount, Quebec 1989)

Mrs. Ethel Renouf (ed.), The Black Whale Cook Book: Fine Old Recipes from the Gaspé Coast Going Back to Pioneer Days (Montreal 1948)

Jennifer Stead, “Sea Pie,” Petits Propos Culinaires 38 (August 1991) ‘Notes and Queries’ 66-67