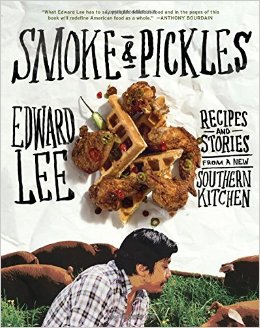

A multicultural gem that beats the odds embedded in its genre: Edward Lee’s Smoke & Pickles: Recipes & Stories from a New Southern Kitchen.

1. Faddish food and feckless ‘branding.’

In culinary terms the American south is all the rage. It seems as though more cookbooks touting southern foodways roll from the press than any other genre. Lots of celebrity chefs, and would-be celebrities, attempt to cash in on the fad, to gain publicity for their restaurant empires through publication of what amounts to promotional material as opposed to manuals for practical application in the kitchen.

Many of them are entirely aspirational. These books are exercises in “lifestyle branding,” a dreadful term and baleful practice. The ‘author,’ frequently ghosted, tells colorful stories about his upbringing, ferocious kitchen exploits and recruits famous ‘friends’ to extol the virtues of his personality, charitable work and, incidentally, food.

The formula is taken to more fevered favor if the author chef can boast an impoverished background, pronounced ethnicity or incongruous locale.

2. Beating the odds.

Oddly enough, however, despite the headlong tumble of shallow and useless food porn, some of these books, a tiny proportion, are, despite all appearances and despite all odds, pretty good. One of them, on its surface guilty of every sin just catalogued, is very good indeed.

Edward Lee is a Korean American from Brooklyn who operates a self-consciously southern restaurant in Louisville that tinges its food with Korean ingredients and technique. The results should be uncomfortably awkward, a retrograde return to the failed fusion food of the late twentieth century. The recipes can be faddish as well; lardo cornbread--cornmeal and corn much in evidence more generally--a dozen or so pickles, Kabocha dumplings, a clutch of eccentric remoulades, togarashi cheesecake and more.

Lee competed on Top Chef and likes Karaoke. He tells stories about drunken revels--Bourbon of course is the beverage of choice, and his cookbook is strewn with photographs of Pabst Blue Ribbon, the redneck Bordeaux--and slathers his book with endorsements from local heroes or b-list celebrities.

Names are dropped. Index entries include Kim Basinger, Johnny Cash, Laurie Colwin, John T. Edge, Evan Jones, Wolfgang Puck, Joe Strummer, Jeremiah Tower and Alice Waters. It is an admittedly impressive cast with scant connection to the food Lee cooks.

The title itself, Smoke & Pickles: Recipes and Stories from a New Southern Kitchen , might provoke a weary groan. But persevere; Lee is no Eddy Huang. His personality comes through his writing and it is not unpleasant or unkind. Lee writes well, if in the self-conscious style of the gonzo chef, and comes across as genuine.

3. Some visits to the big house.

His own celebrity bemuses him, and he is candid about his foibles and even about a few fears. Cash for example appears in the context of his famous Folsom Prison concert. It is a dangerous tack for Lee to take on several levels. The selection of the tracks as inspirational fits tight to the macho chef ethos, and so much has been written about the Cash prison concert that anything more risks sounding derivative or trite.

The album itself is every bit as epochal as Lee thinks, however, and in insincere hands any discussion of it would wind up fawning or mawkish, but in his it becomes a vehicle for the exercise of self-deprecation and self-awareness along with a means to understand charity as something primal instead of patronizing.

Initially the music itself was the thing, something Lee says changed his life when he first heard it as a teen. Even now that he has listened to the album “a thousand times” it still moves him. He has, he admits “always wanted to create something that crazy, that important.” (Lee 187)

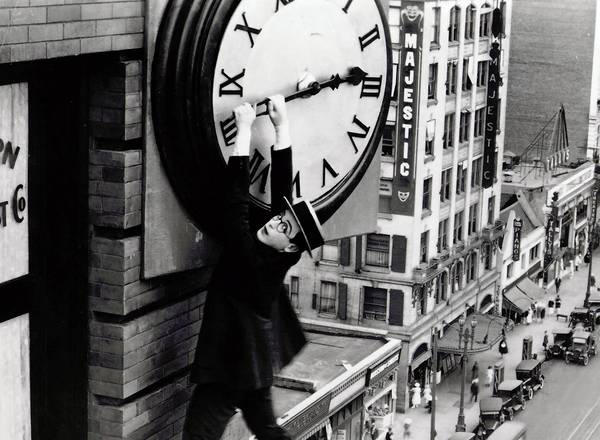

As he has gained stature and riches, however, Lee has understood that, as he puts it,

“time is our most valuable commodity. That extra night it takes to brine a pork loin, that extra hour it takes to let a dough rise, the time it requires to peel fresh garlic makes all the difference in the world,”

not least, he thinks, because “[g]ood food is a gift.” (Lee 187) This of course is the outlook that a good chef or honest cook should take, but to his credit Lee takes the conversation further.

Time, it turns out, is something precious, both to Cash and to Lee, and to convicts, for contrapuntal reasons. So Lee sought to emulate Cash and do a good deed, notwithstanding his understanding that the Folsom gig “was a publicity stunt, and, yes, the final tapes were edited to make the cheers louder,” because Cash’s

“time was a valuable commodity, but the inmates, well, all they had was time on their hands. The convergence of the two was a precious rare moment.” (Lee 188)

It was not that Lee never engaged in the charitable activities peopled by the inmates of the big money society circuit: He did, and did it a lot. He did, however, experience an epiphany following one of his celebrity fundraisers. It is not that Lee sought to engage in class warfare, but rather he

“realized that I had no fucking clue what charity I had just raised money for. This was no one’s fault but mine. I’m sure it was printed on every twenty-foot banner that floated from the ceiling right next to the tequila and wine logos…. And it made me feel both selfish and shallow that I was anything more than hired help in the organization’s fundraising efforts.” (Lee 187)

The impersonal nature of these fêtes contrasted with the intimate sacrifice that had sustained him as a child. After his family, destitute refugees from the Korean War, moved into a crowded Brooklyn tenement, they found to their surprise (and to his suspicious grandmother’s fear of poison) that by custom “the more established families” assisted newcomers with dinner deliveries.

The dishes may have been humble--“mostly vegetables, cheap older vegetables bought at a discount”--but “the charitable gesture made their food taste good, comforting even.” (Lee 187, 188) The offerings did more than that. They exposed Lee and his family (other than the grandmother) to alien foodways, from Jamaica, India and elsewhere in Asia.

Lee longed for the same connection in his own charitable work and decided to emulate Cash in choosing to comfort prisoners. While eager to burnish his testosteronal bona fides (“Now, I am no coward, and I’ve tussled my way through enough fights in my days…. ”), Lee readily admits he found the prison terrifying and horrifying in turn. (Lee 188)

He confides that “even from a distance,” the prisoners “looked like they would eat me alive if given the chance.” He found “the noxious smell of ammonia everywhere” more frightening even before encountering an example of the reason why. When he found a broad map of drying blood at the bottom of a stair, a bored guard shrugged “[i]t happens sometimes” and casually radioed the sanitation crew. (Lee 188) Lee fled.

At the suggestion of his lawyer, he decided to feed the inmates “at a correctional facility for kids nearby” instead and the experience astonished him.

The young prisoners may have committed crimes (“All these kids had made bad choices… ”) but Lee found them “inquisitive and curious and hungry. They were kids” and they loved him. “I consider myself a pretty tough guy,” Lee reminds us (back to those bona fides), “but I never thought I’d have to swallow my tears as these kids smiled and waved goodbye to me in their brown jumpsuits and slippers.” (Lee 189) How could anybody dislike Lee?

3. Three good books with bad first impressions.

In practical terms Smoke & Pickles may be the best of many recent good books of its kind. All of them feature sorghum, pickles (the south as the new Brooklyn), pimiento cheese, Duke’s mayonnaise… and an overwrought persona.

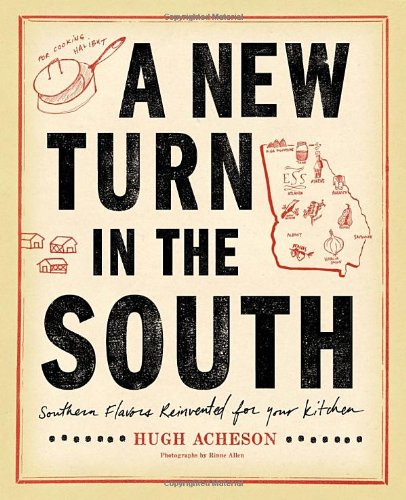

A New Turn in the South from Scott Acheson (Ottowan by birth; operates a southern restaurant in Athens, Georgia, replete with reference to R.E.M.; book endorsed by Mario Batali) takes a modernist approach to traditional southern at once accessible and refreshing.

The ghastly title of Pickles, Pigs & Whiskey: Recipes From My Three Favorite Food Groups (and then some) ” by John Currence, “James Beard Winnin’ City Grocery Ownin’ Oxford Mississippi’s Original Big, Bad Chef” (“Foreplay by” John T. Edge--there he is again) should put anyone off.

The author’s insistence on the false linkage of every recipe to intellectual bad boy bands of the sort who played Maxwell’s in Hoboken, New Jersey during its delirious heyday (Bad Brains, Hüsker Du, L7, Neutral Milk Band, &c &c), to glam bands, alternarockers, or southern immortals like Hank Williams and latterly the great C.C. Adcock’s Louisiana supergroup Lil Band O’ Gold, does not help. The forced references belie Currence’s outstanding original takes on both the southern and creole traditions.

4. But is it British?

What does any of this have to do with British food? More than Lee, or Acheson or Currance for that matter would appear to know, and for good reason. Other countries get their due. As Lee himself explains with some redundancy,

“Louisville sits at the intersection of many different cultures. There’s Southern soul food rising up from the south, a German influence coming down from the north, and country cooking spreading from Appalachia.” (Lee 108)

He might have added Appalachian folkways, and its folkways are its culture, derive from the culture of the Scots-Irish who pioneered settlement of the region. Their isolation for centuries ensured the survival of a recognizable British frontier mentality reflected in their foods.

The reputation of British cuisine remains so traduced, however, that most Americans never notice the British foodways that surround them. Even apple pie as we bake it originated there, not here.

It is instructive to cite but three examples of the unsung sensibility that lies within Lee’s superficially unBritish book.

It’s British you know.

He has two innovative ketchup recipes and Currence, by the way, has one too: The British invented ketchup. Lee bakes a good Chinatown curry pork handpie: The British created curry, and Elisabeth Ayrton has written an entire chapter on the British tradition of the savory pie in her landmark Cookery of England . And deep fried fish anyone? Lee has a recipe for that too; it uses trout.

None of this is to claim a British preponderance for Smoke & Pickles or the other branded books from butch kitchens: It is only to note that the influence lurks within, even on the southern food of an Asian-American chef enamored not just of kimchi and rice bowls but of Bluegrass, Bourbon and brine.