Sea pie: A saga of innovation & transformation

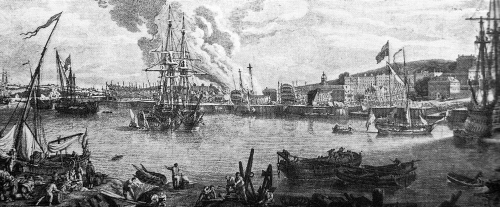

Sea pie, a staple in the Royal Navy of Quiberon Bay, Trafalgar and the Nile, always has been assembled from earthly components. It was a dish originally for eating at sea rather than one utilizing fish, except possibly for the occasional cured anchovy, a seasoning for meat much beloved of both landbound and seaborne Georgian cooks.

Before the advent of canning or refrigeration, preserved food was dried or salted food. Early versions of sea pie therefore consisted of salt beef or pork, ship’s biscuit and little else except for some hard cheese or a precious onion, which did not keep for long onboard humid ships, to zap things up.

None of this has prevented food writers from conflating the original sea pie with seafood, further evidence of our recurring observation that much food historiography is bad.

In the otherwise exemplary Au Pied de Cochon-The Album, Jean-Francois Boily describes with misplaced authority

“the original English ‘sea pie’… which, as the name implies, was made with various types of fish and seafood. The evolution of this dish did not, however, stop there. It began to include all sorts of farm meats and local game,” at least in Quebec, but more on that later. (PDC 70)

To paraphrase M. Boily, the evolution of sea pie did not start there either, for there is no evidence of an early dish with that name based on fish.

Mark Morton in Cupboard Love: A Dictionary of Culinary Curiosities, claims that the pie is made “by alternating layers of meat, fish and vegetables with broken biscuits” and that it “does not really have anything to do with the sea or pie.” (Morton 273) He is wrong on all counts but the biscuit. The Editor never has found reference to combining meat with fish in any of the many sea pie recipes ranging from eighteenth century England to twenty-first century Canada; has not always seen the inclusion of ‘vegetables’ other than onion and the occasional potato; and believes most emphatically that sea pie did originate as a maritime dish, a covered pie that could be steamed on a ship unequipped with an oven as well as baked on a bigger sailing vessel that featured one.

Most researchers date the first printed recipe for sea pie to Hannah Glasse in 1747. It is from her chapter “For Captains of Ships” in The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy and called “A Cheshire Pork Pye for Sea.” Here it is:

“Take some salt pork that has been boiled, cut it into thin Slices, an equal Quantity of Potatoes, pared and sliced thin, make a good crust, cover the Dish, lay a layer of Meat, seasoned with a little Pepper, and a Layer of Potatoes; then a Layer of Meat, and a layer of Potatoes, and so on till your Pye is full. Season it with Pepper; when it is full, lay some Butter on top, and fill your Dish above half full with soft Water. Close your Pye up, and bake it in a gentle Oven.” (Art 125)

This, however, is not the Royal Navy’s sea pie, and perhaps not the true antecedent of the pie in general. The navy was among the first European institutions to successfully convince its people to eat potatoes, but again the dearth of evidence linking the tuber to something originally called ‘sea pie’ is striking. Nor does Glasse use either biscuit or suet pastry, and sea pies were not necessarily baked while at sea.

Another writer explains that during the Georgian era, sea pie was something that

“can be made in a saucepan to cook on top of the stove, or in a casserole for the oven. It consists, quite simply, of a good rich stew with a suet pastry crust… (ie basic duff mix).... ” (Macdonald 190)

Now we are getting somewhere, piloted by the capable Janet Macdonald. To backtrack for a moment, the essential suet pastry of what the Editor recognizes as sea pie evolved as ships’ stores eventually included suet during the eighteenth century to make ‘duff,’ the staple pastry used for all manner of sweet as well as savory puddings to boil in ships’ stoves or bake upon pies. Stores of suet became standard in United States Navy manifests later, by 1813. (Macdonald 142)

Fueled by sea pie.

Macdonald stands on firm ground in broadening the definition of sea pie to include all manner of ingredients, fresh and varied as well as cured and limited, if we are considering what Nelson’s navy actually ate. When ships’ pursers could obtain fresh meat and vegetables at sea, and Macdonald is convincing in her conviction that they frequently could, those ingredients went into pies, as they did in Britain proper. In culinary terms, however, what sets the sea pie of the eighteenth century apart is the relatively limited range of ingredients carried within the wooden world when the equivalent of marine forage was unavailable.

As an aside, this unavailability did not extend to fresh fish, even though the standard ration jettisoned the unpopular salt fish as unhealthy over the course of the eighteenth century. Royal Navy warships carried skeins and orders to fish with them whenever possible, and Macdonald also is convincing in her assertion that ships’ crews did sup on fresh fish, so an absence of them does not explain the absence of evidence for a fishy sea pie.

Standard Admiralty issue included meat and stuff for duff (flour and suet) of course, beer and cheese; dried herbs and spice (at least for the officers) also frequently shipped in galleys. Ships’ logbooks ‘most commonly mention’ cabbages, onions and leeks among fresh vegetables acquired at sea “when opportunity permitted.” (Macdonald 36-37) An authentic sea pie therefore ought to include a filling of beef or pork and onion or leek, thickened with flour, seasoned with dried herb and sauced with beer under a lid of duff made with some gratings of the cheese mixed into its suet.

That is the dish that Theodora FitzGibbon, one of the best food writers of any age, considers sea pie. Janet Macdonald has noted that onions feature more than any other fresh vegetables in ships’ logs from the Georgian navy, and observed that cheese was standard Admiralty issue. “Those onions would brighten any savoury dish, as would cheese.” She also explains that the officers at least had “plenty of varied meats” onboard ship. (Macdonald 134) Mrs. FitzGibbons’ recipe therefore is authentic in its use of beef and onions; the beer is porter, the most popular of eighteenth century brews in England; and britishfoodinamerica chooses dried bay and thyme. Ships carried bottled sauces and ketchups too, and cayenne, so in they go beneath a spongy suet cap spiked with sharpest Cheddar.

Other pies also deserve the marine appellation (but should not contain fish), because sea pie slipped the bounds both of Britain and its fleet. The dish “was soon found serviceable for hungry landlubbing families as well” as sailors, and Amelia Simmons includes a version in the first cookbook published in America by an American author, her American Cookery of 1796. (Northern Hospitality 260) It exhibits flexibility and an adaptation to New England conditions with the inclusion of mutton, pigeon, turkey, veal “or birds” along with the salt pork.

Sea pie has proven versatile. In 1936 the Fianna Fail department of Agriculture published a recipe for sea pie in Ireland. It is, according to Regina Sexton, “originally not of seafood but of meat, vegetables and potatoes, baked with a suet pastry lid.” Sexton finds the name “curious” while incongruously, and properly, noting that “[t]he name arose because it was often served at sea to sailors.” (Sexton 32) Her own recipe from A Little Book of Irish Food omits the potato despite Sexton’s attempt to nationalize the dish by substituting a less satisfactory top crust of soda bread, adding stout and renaming this most British preparation “DeValera’s Pie.” This inadvertent invocation of irony is typical of an irritating book, for DeValera was nothing if not an Anglophobe and champion of cultural autarky.

Back in Britain, sea pie resurfaces as a ration book recipe during the Second World War. According to Nicola Humble, wartime exigencies and attitudes tore recipes from their historical moorings. “Only significant as a way of using the available foods as efficiently as possible, the instructions for individual dishes began to lose their cultural meaning. So historical specialties like Glamorgan sausages are recast as Semolina Cheese Sausages (in Mrs. Arthur Webb’s 1939 War-Time Cookery)…. ” (Humble 93) The Editor is not so sure. As Jane Grigson notes, “[t]here are many recipes for Glamorgan sausages. The ingredients are always the same, but the proportions vary.” (Grigson 30) The reason why Mrs. Webb ‘recast’ her recipe is obvious; its ingredients are not the same as the traditional ones for Glamorgan sausages, particularly its substitution of semolina for scarcer breadcrumbs and addition of milk to stretch the single egg in her recipe: Under rationing the traditionally more extravagant proportion of eggs became impossible.

At other times when Mrs. Webb renames a modified traditional recipe, we find it more plausible that she was attempting to do what other wartime food writers and the Ministry of Food itself were doing. They made every effort both to encourage improvisation--as Mrs. Webb did in her substitution of semolina--and to excite palates numbed in monotony by recasting the old as new. A preparation modified to meet wartime shortages may acquire a new name, but not necessarily an a-historical one, so her sea pie becomes disguised, most thinly, as a “Mariner’s Casserole.” It is not, strictly speaking, a sea pie by our lights only because of its overloaded potato content, six of them intended to stretch a mere 12 ounces of combined beef and pork. There is less an element of rootlessness, more one of honesty, to War-Time Cookery.

Mrs. Webb’s reliance on the potato does have an antecedent from the 1920s. Richard Bond’s recipe from The Ship’s Baker, designed for an institutional scale galley, is positively parsimonious in its use of fifteen pounds of potato to “3 or 4 lbs. beef or mutton,” and his pastry is striking in its low proportion of suet to flour, one to five, rather than the more usually encountered ratio of one to three or two. (Bond 351)

The reference to mariners by Mrs. Webb may be closer to original usage than first appears, and perhaps playful, for, as Lizzie Boyd notes, sea pie also was “known as sailor pie, possibly because this was the nearest sailors at sea came to a traditional beef suet pudding.” (Boyd 320) Her version simmers on the stove but may as easily bake in an oven.

The most striking transformation of sea pie, in etymology and substance, has occurred in an unlikely place. Sea pie had acquired the phonetically congruent name of cipaille and variously six-pate by 1998 in anti-Anglophone Quebec, where the British roots of the dish are not only unmistakable but, somewhat surprisingly, also acknowledged. It is a dish that is embedded in the folk memory and contemporary kitchens of the province and, as noted by M. Boily,

“The variations in spelling are nonetheless not as numerous as are the variations in the recipe. It is common knowledge that there are as many ‘official’ recipes as there are ancestral Quebecois families, each of whom have been handed down their own true version from a venerable forefather lost in the mists of time.” (PDC 70)

The Quebecois recipes for sea pie are good ones, even richer than their hearty British cousins and bearing the stamp of the colder north. As its alternative ‘French’ name indicates, it sometimes appears inter-layered with six sheets of pastry rather than a single topcrust. Cooks in the Royal Navy sometimes did something similar in constructing ‘tripledeckers’ for hungry crews, but the Editor has not found the first recorded instance of that improvisation.

Captain Abraham Crawford dined on a “‘three-decked sea-pie’ much enhanced with onions” at some point in the first half of the nineteenth century (Macdonald 135), and a “three-decker” “made on nautical lines” features in the fiction of Patrick O’Brien. (Far Side 83) In Lobscouse and Spotted Dog, “Which It’s a Gastronomic Companion to the AUBREY/MATURIN NOVELS,” however, the authors mistake a multicrusted raised pie made with “hot water paste” for the real thing made with suet sponge. (Lobscouse 21)

Cipaille too has lost the suet pastry of its forebears; not surprising since the preparation is not known in France, where the language has no word equivalent to ‘suet.’ Versions in Quebec use pate brisée instead.

Gisele Beaulieu’s good recipe uses beef, chicken, fresh and salt pork, onions and potatoes, seasoned with the characteristic ‘mixed spice’ of both Britain and Canada; allspice, cinnamon, clove and nutmeg (or, in Britain, mace). Other cooks along the St. Lawrence prefer a combination of game in the guise of pheasant and venison when they can get it. (Armstrong 26)

The best and most difficult cipaille to cook may belong to Martin Picard, the chef and proprietor of Au Pied de Cochon in Montreal and M. Wells Diner in Long Island City. It also may be the richest despite its single layer of topcrust.

The best and most difficult cipaille to cook may belong to Martin Picard, the chef and proprietor of Au Pied de Cochon in Montreal and M. Wells Diner in Long Island City. It also may be the richest despite its single layer of topcrust.

Picard is a maniac in the best way, a devoted and innovative cook utterly lacking in political correctness or pretense. His restaurant in Montreal “revels in extremes, from the seasonal changes in the menu, to the gut-defying volume of the portions served and the joyous chaos which pervades the place…. ” No décor but Picard’s own subversively witty drawings, no linens on tables, no uniforms: “Professionalism at Au Pied de Cochon stands in no need of such vain trappings.” (PDC 11)

His cipaille includes duck, hare, pork, quail and venison; onions and potatoes; both pork stock and onion soup; cinnamon, clove and savory. Best of all, he stands a vent of marrowbone in the center, to help crisp the crust and to roast, an enhancement to any hot pie that we feel stupid not to have considered ourselves. Some of the marrow oozes to enrich the pie and the rest makes a silken bonus scoop. Now, thanks to Picard, we are adding marrowbone to many pies at britishfoodinamerica.

And now that sea pie has landed in Quebec, it is time to reintroduce this most comforting food to Americans. As Janet Macdonald says preceding her own recipe, “Eat like a sailor.” (Macdonald 184)

Recipes for sea pie appear in the practical.

Sources:

Julian Armstrong, A Taste of Quebec (Toronto 2001)

Richard Bond, The Ship’s Baker (Glasgow 1923)

Lizzie Boyd (ed.), British Cookery (Woodstock, NY 1979)

Hannah Glasse, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (London 1747)

Anne Chotzinoff Grossman and Lisa Grossman Thomas, Lobscouse and Spotted Dog (New York 1997)

Nicola Humble, Culinary Pleasures: Cookbooks and the Transformation of British Food (London 2005)

Janet Macdonald, Feeding Nelson’s Navy: The True Story of Food at Sea in the Georgian Era (London 2004)

Mark Morton, Cupboard Love: A Dictionary of Culinary Curiosities (London, Ontario 2004)

Patrick O’Brien, The Far Side of the World (New York 1992)

Martin Picard et al., Au Pied de Cochon-The Album (Montreal 2006)

Regina Sexton, A Little Book of Irish Food (London 1998)

Amelia Simmons, American Cookery (Hartford 1796)

Keith Stavely & Kathleen Fitzgerald, Northern Hospitality: Cooking by the Book in New England (Amherst, MA 2011)

Mrs. Arthur Webb, War-Time Cookery (London 1939)