In search of the elusive but resilient Snaffles mousse with an Appreciation of Lady Mollie Cusack Smith.

1. Some stars align in Dublin.

Back in the 1970s, fashionable Dublin, or at least what then passed for fashion there (the decade predates its entry into the twentieth century), flocked to Snaffles. Its patrons included foreigners, some of them famous, who were eager to pay a premium for good food in what remained for the most part a culinary desert.

The place was an innovative hybrid, particularly in the Irish terms of the time. Snaffles served seasonal foods; game, roasted small birds a specialty; fish: and shellfish, to honor the Anglo-Irish tradition, but also blow-ins like ratatouille and its chefs’ own creations.

According to Martin Dwyer, who worked in the kitchen during its heyday, diners included John and daughter Angelica Huston, and Ryan O’Neil with Tatum, who would make “long reverse charge telephone calls from the phone in the kitchen to her pals in LA. A brat of the first order.” (Dwyer)

They had been filming on location in Ireland. Fellow patrons Stanley Kubrick and Marisa Berenson, like the elder O’Neil engaged in the production of “Barry Lyndon,” showed up, but not Paul Newman; he had assumed the restaurant was closed because entry past its locked door required ringing a bell. (Dwyer)

Athletes, Irish and otherwise, appeared in Snaffles, including Virginia Wade “being snogged by someone in the corridor” (louche Ascendancy ways lived on in Dublin) and politicians too, including Taoiseaches and even Edward Heath from over the Irish Sea.

The crew at Snaffles

2. Good golly.

Then there was the Lady Mollie Cusack Smith, stunning beauty, “frequent customer and a loyal fan.” (Dwyer) She sounds like the best of the bunch; quick-witted and colorful, a woman who could swear like a sailor as well in Gaelic as in English, and did. Once she happened upon a senior clergyman of the (protestant) Church of Ireland at Bermingham House, her grand and dilapidated seat near Tuam in north Galway. He had arrived early for a party. The chatelaine promptly told him to “get the fuck out of here” while she completed her preparations, this in an age of considerably greater politesse than our own. (O’Toole)

It was no isolated incident. One inhabitant of north Galway commented that “you know you are accepted when Molly [sic] has told you to “Fuck Off.” (Cooney)

Burke via Gilray

Unlike most Big Houses, Bermingham had survived both the arson of the IRA and the Republic’s punitive taxation; Lady Mollie would live there until her death in 1998. Like Burke before her, Lady Mollie straddled the sectarian divide. Her father The O’Rorke of Breffni headed one of the great Gaelic families “who for centuries paid obedience to the Anglo-Norman monarchs largely to safeguard their succession rights, which was not possible under the Irish clan system.” (O’Toole)

She became a Lady upon marriage to a baronet, Sir Dermot Cusack Smith, whom she met at a cocktail party in wartime London. “He was very rich and had a title,” the Lady later explained. “We got engaged because it seemed a good idea but it wasn’t.” (O’Toole) She would take their divorce in stride.

An only child who cheerfully confessed as an adult that she had been “thoroughly spoiled,” the future Lady Mollie rode to hounds with her father at the age of ten. Her prowess in the saddle was peerless and she would become the first (and only) female Master of the North Galway Hunt for a period of some four decades. (Irish Independent; O’Toole)

One day the Master returned to her stables astride a blown and sweaty horse. Said the groom: “Jassus Maam you have him in a terrible lather.” Said the Lady: “So would you my good man if you had been between my thighs for the last four hours.” (Dwyer; O’Toole)

Before then she had quarreled with her father over the horses and followed the path of the Wild Geese to France, ostensibly to study opera. Instead she became a cordon bleu cook and prospered in Paris as a designer in the cutthroat world of haut couture. The Lady sat for Augustus John, possibly, or possibly apocryphally, naked as well as clothed. He called her “The Tulip of Tuan.” (“Tulip”)

John’s crony ‘Fireball’ McNamara called Lady Mollie a “great friend’ of them both. Apparently nothing made the Fireball happier than sailing an improvised schooner in turbulent waters with terrified young women onboard. The seventeen year old Mollie, however, was not scared. She was, he said, “a wild one,” an intrepid sailor who steered the boat up thirty foot swells “like a cat climbing a wall, in Molly’s words.” (“Tulip”)

Her postwar dinners were legendary affairs, not least for her flair, which could include rousting tardy diners from the bar with a blast from her hunting horn. (O’Toole) The grandest of all was the annual hunt ball. It was “a free-for all that [took] over every room in sprawling Bermingham House. Unrestrained by concierges or curfews, it ha[d] all the ferocity of an unsaddled hunt.” (Cooney) The ball would rage on for days, “ending in Paddy Burke’s, Clarinbridge, for oysters.” (“Tulip”)

This formidable woman did more than entertain on the grand scale. She was a “sacred monster” who ruled her corner of north Galway as if the Ascendancy still held sway. And she charmed everyone. Writing in 1995, when Lady Mollie was eighty-nine years old (but “aged anywhere from 84 to 94 depending on her mood”), Patrick Cooney explained:

“She is still beautiful, and defies the years of hard living and tough hunting…. With a tongue like a hatchet and a cruel wit, she is both loved and feared; and, at an age when, frankly, most people are dead, she is still lording it over the locals, who adore the abuse and wonder what it will be like ‘when Molly is gone.’” (Cooney)

This was all the more remarkable because it was based on bluff. Like generations of Ascendancy grandees, Lady Cusack Smith lived in straitened circumstances.

“There wasn’t much money, but she lived with a certain Spartan style. When money was particularly scarce, she would retire to the gatelodge, and rent the house. There was a sensation when Mick Jagger and Marianne Faithful stayed there in the 1960s. She drove a noisy Volkswagen Beetle into Tuam for provisions, and large gins in Brown’s pub.” (“Tuam”)

3. Fearless folks.

The Lady knew no fear in circumstances large or small. She once stood her ground as a farmer, irate over the path the path that hunters took across his land, tried to stone both her and horse. “A member of the part who stayed to give her support was rendered speechless by the ferocity of her attack.” (O’Toole) One time at Snaffles during the 1970s she intervened to allay the disgust of a tablemate. Her guest had found a fly in the gravy so Lady Mollie downed the contents of the jug, swimmer and all, shouting “More Gravy John!” to the waiter. (Dwyer)

Lady Mollie herself.

Back then, Snaffles and a mere couple of competitors operated in the best, that is to say innovative, amateur tradition. As the Firuskis, husband and ex-wife, have said of the great Marcel Boulestin:

“He did not know the tricks of the trade. But he knew food and he knew how to cook. In other words, the problem was approached from the point of view of the client. The professionals regarded him as a talented amateur, with a half-contemptuous and ‘half-pitying tolerance.’ Little did they realize the value of the word amateur.” (Firuski xvii)

With so few choices for decent food in Dublin, they owned its market. Their chefs were able to cook what they liked and neither stinted on convenience nor limited themselves to luxury ingredients. You could get away with that in the seventies, before palates could ferret out every flavor or test a dish for its constituent parts in a laboratory something like a culinary CSI.

4. A secret at Snaffles.

And so was born the legend of Snaffles mousse. Its recipe was secret, and before relenting with the publication of The Good Food Dinner Party Book and then Countryhouse Cooking, the restaurant ostentatiously refused all entreaties to disclose it.

Diners at Snaffles found its mousse beguiling and attempts to reverse engineer the recipe consumed obsessive customers. According to Dwyer, the competing critics, each authoritative, described its contents in contrasting ways:

“A creamy froth of smoked fish;

Like a savoury Guinness, smooth creamy and garlicy [sic];

Seafood, probably mainly lobster or crab, very light and airy, exquisite

and unobtrusive; and

Soft, cold with liver and other flavors.” (Dwyer)

The flavor of Snaffles mousse is elusive.

In fact the restaurant kept its secret out of fear. As Dwyer confesses, “[t]he truth of the matter was that its ingredients were an embarrassment to us.” (Dwyer)

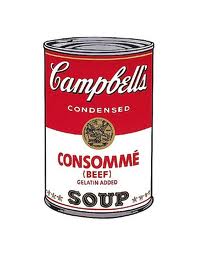

They consisted solely of canned Campbell’s consommé, a pinch of commercial curry powder, a little crushed garlic and a slab of Kraft’s own Philadelphia cream cheese. We wonder what they charged at Snaffles for this humblest amuse. If all of this, or what little there is, invites disdain or spins the head of any new traditionalist, however, she has not tried the mousse.

The people who ate at Snaffles during the 1970s were neither antediluvian primitives (remember that Shakespeare could write) nor seized with a collective culinary dementia. Snaffles mousse is not only superb, it also is one of the few genuine Irish contributions to human cuisine.

5. Italian interlude.

The combination of ingredients tastes different from and more complex than its parts, much like the recipe for Pollo alla Toscana by Valentina Harris. Her pollo, found in Recipes from an Italian Farmhouse, is a dinner party staple of the Editor. The dish is very nearly foolproof and guests never guess what goes into it, which becomes the foundation for an amusing parlor game. The preparation requires nothing more than the chicken, some dried porcini, a little tomato sauce, white wine and roux, but people insist variously that it also relies on ground almonds, anchovy, bacon, brandy, garlic, onion, turmeric, even paté.

6. The secret shared.

Unlike the foolproof pollo preparation, the elusive froth from Snaffles can be problematic. The recipes published in Dinner Party and Countryhouse Cooking do not work, or at least work no more. Our mousse based on them never set; it remained watery and tended to separate. Dwyer claims that the consommé in question “no longer has the requisite gelatin to set this mousse” and so passes on a successor recipe. It changes the original proportions, substitutes curry paste for the powder and adds a leaf of gelatin. This one works.

Before the food snobs scoff, they ought to know that the alternative recipe reputedly comes via one of their gods, and a powerful one, the revered Simon Hopkinson. Dwyer and various websites maintain that Hopkinson wrote about the mousse in his column at The Independent during 2000, but the paper’s search engine will not allow the Editor access before 2003 and no such article emerges from any other online source.

In a rare lapse of rigor, however, the Editor will take Dwyer’s invocation of Hopkinson on faith. The original Master of the Mousse would have no incentive to betray culinary religion and perpetrate a hoax. Dwyer describes the uprated version as “an improvement” on his own while giving Hopkinson complete credit for the change, not only to compensate for the reduction in Campbell’s viscosity but also for enhancing the flavor of the final product. Dwyer likes the substitution of curry paste for his original powder and adds the generous comment that Hopkinson “also says to serve with hot buttered toast, which we never did at Snaffles but sounds like a nice addition.” (Dwyer)

7. A mousse by any other name….

The story could end there as a good one but wait, there is more. Snaffles mousse has enjoyed a humble if often anonymous afterlife in print and online. An undated entry at www.soupsong.com, for example, provides a modified recipe for Snaffles mousse disguised rather lumpishly as “Solid Soup.” It was, according to the site, “a favorite of socialite Marylou Vanderbilt Whitney.” Was she amongst the glitterati infesting fashionable Snaffles back in the day? We do not know, and ‘soupsong’ gives nobody other than the socialite a nod for the recipe, but its lineage is obvious.

Notwithstanding this element of plagiarism, the anonymous introduction at ‘soupsong’ is of value to both cook and thespian:

“It sounds like it should be easy to make and awful to eat. In fact, it’s the reverse. Very tasty above and beyond the eyebrow-raising presentation… but pretty tricky to get right. Serve cold, obviously… but before sweeping them [your guests of course] into the dining room. The whole point, I think, is a sophisticated conceit: instead of moving into the drawing room after dinner to take a demitasse of coffee, you begin in the drawing room with what LOOKS like demitasse coffee as a prelude to the dinner.” (emoting emphasis in original)

Of course this makes the unwarranted assumption that all of us have both drawing and dining rooms but no matter; britishfoodinamerica grants its readers the indulgence to serve Snaffles mousse at table, and not necessarily in a demitasse. A small glass or ramekin works better anyway.

Gourmet picked up the recipe in 1972, allegedly from a reader but probably from the Dinner Party, and published it as “Curried Cream Cheese Spread (Snaffles Mouse).” The defunct magazine’s version, inferior to ours, remains available online at www.Epicurious.com.

8. An enduring nexus.

Molly O’Neill unwittingly discussed Dwyer’s creation in The New York Times during the 1996 holiday season. She had interviewed Lee Smith, a writer whose novels focus on the daily lives of southern women. Cooking is a major theme in Smith’s life as well as work, a means of keeping faith with her family and their past. “Indispensable” Christmas dishes in the Smith household include some kind of roast bird, her grandmother’s cheese biscuits, “garlic mashed potatoes that her step-daughter perfected, the cranberry chutney that has just always been around” and “the curried mousse that Smith once sampled at a Florida animal farm.” (O’Neill)

This last is Snaffles mousse travelling under an alias; Smith admittedly did not know its provenance. Maintaining holiday traditions is important to people, even if their sources are not, and Smith’s Christmas dinner tells us something about both southern food and its pedigree.

The recipe appended to the article by O’Neill indicates that the cheese biscuits are cheese straws, which as britishfoodinamerica has noted, arrived from Britain to become a southern icon more beloved there than in its place of origin. Chutney is another staple that the south has made its own by modifying the British model. And then the Snaffles mousse, as far as Smith knows a Floridian product but instead something that emigrated out of a rowdy Dublin kitchen from the swinging sixties.

In O’Neill’s original rendition, however, the recipe has lost a lot in translation. It calls for ‘beef stock’ without gelatin and therefore fails even more miserably than Tinne’s Countryhouse decomposition. O’Neill must have figured that out; four days later she issued a correction in The Times to meliorate if not rectify the problem by switching the stock to consommé.

Then in June 2008 the recipe appeared in the South Florida Sentinel-Sun, a daily based in Fort Lauderdale that trafficks primarily in local news. Perhaps the mousse had found its way to the city from the animal farm. The flack who presented the dish gave Snaffles no credit and apparently did not actually prepare it either.

In this cloying incarnation saddled with the dreaded ‘half-and-half’ the dish is called “Chilled Beef Consomme with Curry Accent” (what a wordsmith) and described as “a distant cousin of the clear consommé we generally associate with the name.” Distant indeed with all that cheese and the curry, but the Sentinel-Sun does concede, if not speculate, that “it has much more flavor and consistency” than the light broth.

Finally for purposes of this essay a blogger at ‘The Greasy Spoon’ wrote about our subject three months after the Sentinel-Sun. “The Fabulous Snaffles Mousse” notes the juxtaposition of its “hilarious” constituents and “sophisticated” taste, a fair point.

He also offers his own version based on the AWOL Hopkinson essay. It owes an apparent debt to Dwyer, who is not cited but who himself had posted the recipe in January of the same year. After all, Hopkinson is the object of ‘The Greasy Spoon’s’ admiration, “my number one culinary hero and what he says and does, in my eyes can do no wrong.” The god abides.

So Snaffles mousse lives on, at least in the kitchen of the Editor and, perhaps, in yours.

Recipes for Lady Mollie Cusack Smith’s Bermingham chicken, for Snaffles mousse and for Pollo alla Toscana appear in the practical.

Sources:

Anon., “Death marks the end of a flamboyant era,” The Irish Independent (18 February 1998)

(author unknown), “The Tulip of Tuan and other flowers,” Galway Advertiser (14 January 2010)

Patrick Cooney, “A Passion For Hunting,” The Independent (18 March 1995)

www.martindwyer.com/m/archives

Elvia & Maurice Firuski (ed.s), The Best of Boulestin (Kingswood, Surrey 1952)

Valentina Harris, Recipes Rom an Italian Farmhouse (New York 1990)

http://lukehoney.typepad.com/the_greasy_spoon/208/2009/snaffles_mousse.html

Molly O’Neill, “Molly O’Neill”[otherwise untitled], The New York Times Magazine (22 December 1996)

Michael O’Toole, “Obituary: Molly Cusack Smith,” The Independent (21 February 1998)

http://soupsong.com/rsolid.html

Rosie Tinne, Irish Countryhouse Cooking (New York 1974)