The global wanderings of marmalade featuring a melancholy note on American Exceptionalism.

The global wanderings of marmalade featuring a melancholy note on American Exceptionalism.

In 1985, C. Anne Wilson wrote a short book about jam. It is what may be considered a ‘small’ one too; The Book of Marmalade makes no pretense of searching for the social or political importance of the product, or of finding any greater significance in it than its flavor. The book is only a straightforward narrative about the history of an unlikely British commodity with appended recipes, and none the worse for that.

Wilson is a good writer and The Book is fun to read. Some needless repetition ought to have been caught by an editor, but no matter. It passes by the reader with minimal irritation, overshadowed by the erudition of the author and her enthusiasm for the subject. Later writers of single subject food histories might have done well to model themselves on Wilson’s work instead of drafting their bloated and portentious efforts.

But once again we digress. Did you know when marmalade first appears in print in Britain, and how it got there? We had no idea before reading The Book. The first orange marmalade recognizable as such appears in 1681, when Rebecca Price wrote down the formula for “marmelett of oringes: my mother’s receipt” in her own kitchen manuscript. It would, according to Wilson, “have been equivalent to the thickest orange marmalades made today, and perhaps thicker still,” which sounds quite good. (Wilson 47)

Earlier marmalades did not resemble the preserve as we know it. They initially were akin to membrillo, the Spanish quince paste for cutting into slabs to accompany cheese. Early Europeans ate it for dessert. Quince was in fact the earliest and, for the Romans, only marmalade. Wilson explains that other fruits could ripen while preserved in honey, so Roman cooks had no incentive to cook them and therefore failed to discover the thickening properties of their pectin. Not quince; it remained unpalatably unripe in its honey bath and an early version of marmalade ensued when the Romans heated the combination. (Wilson 19)

The earliest marmalades made in England set citrus peel in a thin apple jelly, often flavored with beaten fennel seed, cinnamon water, lemon juice and rosewater, separately and in various combinations. (Wilson 44) The first recipe in print for a “pippin-free orange marmalade” appears in 1714; it is a less modern version than the one in the Price manuscript, pounded in a mortar to a uniform thickness. (Wilson 48)

The first landing of oranges in Scotland appears at the Edinburgh port of Leith in 1497; the first Scottish recipe for marmalade was not printed until 1736, another ‘beaten’ preserve recorded by Mrs. McLintock in her Receipt for Cookery and Pastrywork. The Scots, however, already had made up for lost marmalade time. They were the first people to eat marmalade for breakfast instead of dessert, earlier than the appearance of Mrs. McLintock’s recipe, at the outset of the eighteenth century, and they never looked back. (Wilson 58)

By 1797, James Keillor had established the first commercial marmalade operation, at Dundee, and immediately began shipping the product both to Edinburgh and English cities; various brands already would become widely available in London during the early 1800s. Commercial producers, some now lost, proliferated in both nations. (Wilson 60, 61, 64-65)

Crosse & Blackwell sold marmalade from its foundation in 1830; W. P. Hartley followed suit during the 1850s; James Robertson started making ‘Golden Shred,’ a good product that remains on the market, at Paisley in 1864; and Baxter’s, originally a grocer in Fochabers, Morayshire, in 1868.

The Baxters, husband and wife, had been servants at a Big House; its owners and their guests provided the first, ready, market for conserves made by Mrs. Baxter. The Robertsons started out the same homely way, he marketing her marmalade to eager local buyers before expanding the operation to reach the all of Britain and beyond. (Wilson 70-71)

Three Scottish brands survive but only Baxter’s is produced there; three family firms unfettered by multinational food factories, Baxter’s along with Wilkin of Tiptree and Duerr’s, remain in Britain. (Wilson 72, 104)

Meanwhile, however, Wilson has guided us through the Victorians and their marmalade, factory production on the grand scale, and the impact of wartime and austerity rationing on this most British of foods.

She takes us abroad too, to Africa, India, Australasia and of course North America. It became big throughout the empire but, alas, we remain blighted in the United States. Marmalade never caught on outside a few outposts like the Editor’s house; her favorite may be Wilkin’s Tiptree Tawny, a dark preserve loaded with thick slabs of peel that has the added appeal of ‘tawny’ typeset in the shape of a lion on its label.

The Scots got Canada a better deal than Americans:

“Further north, in the Canadian provinces, British food traditions became dominant among the English-speaking population after 1761. Scottish settlers ensured that orange marmalade arrived as a breakfast food and it was the Seville orange marmalade familiar in Britain,” none of the sickly sweet and pallid stuff passed off by American makers. (Wilson 121)

Get a copy; read the book. Meanwhile, the earliest recorded shipment of marmalade, quince, arrived from Portugal, the oldest ally, back in 1495. (Wilson 11)

Prospect Books reissued The Book of Marmalade in a second revised edition as part of its ‘English Kitchen’ series during 2010; a first Prospect revision preceded it in 1999. Both books are aptly illustrated and, like everything Prospect prints, have exemplary production values.

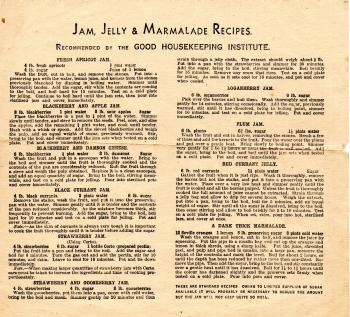

Some recipes from The Book that feature marmalade appear in the practical.