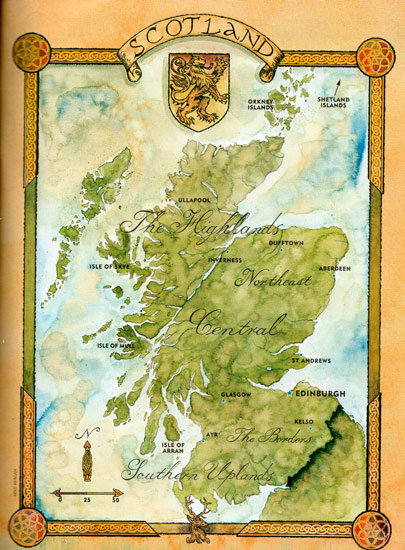

A note on the origin of Scottish foodways, featuring a southward rather than easterly gaze.

In The Oxford Companion to Food , Alan Davidson recognizes that

“Scotland, to venture an understatement, is not at all difficult to distinguish from England; the differences leap to the eye in many different aspects of the two cultures, including notably food and cookery.” (Davidson 705)

In tracing the development of this distinctive cuisine it is particularly important not to succumb to the sentimental, anachronistic and frequently anti-English nationalism that clouds some of Scottish historiography. The trap has ensnared even the ablest food historians, not least Christian Isobel Johnstone, F. Marian McNeill, Jane Grigson, Annette Hope and Catherine Brown, on the subject of the celebrated ‘Auld Alliance’ between Scotland and France. It is said to have lasted, however limited in actual extent, for centuries after the marriage of James V to Mary of Guise in 1538. The alliance receives widespread credit, from Davidson as well as those Scottish luminaries, for influencing Scottish foodways; French hachi the precursor of haggis, hutaudeau of howtowdie.

The strength of this myth is sufficient even to overcome the obvious. For example, the editor of Lady Castlehill’s Receipt Book , which reproduces a selection of recipes from a manuscript dating to 1712, claims that they “reveal a strong continental influence…. but the English influence… is not yet present.” ( Castlehill’s endboard)

The recipes themselves rebut the notion; haggis, lamb stuffed with oysters, manchets, marmalade, a number of pies, syllabub, wigs, white puddings and much more bear a recognizable English cast, while dishes with a French or any other ‘continental’ pedigree are nowhere in evidence. Elsewhere the same writer even quotes Dr. Johnson observing that “a dinner in the Western Islands [of Scotland] differs very little from a dinner in England.” ( Castlehill’s xii; brackets in original)

Whatever economic, political or social interaction Scotland and France shared, it did not extend to the kitchen. Culinary influence did not arrive in Scotland via France. Haggis in fact is of English origin and the term predates ‘hachi’ by centuries, while howtowdie is by no means recognizably French. As Peter Brears observes, “we must first debunk the Auld Alliance as a culinary influence” to understand the evolution of Scottish cuisine. (Brears xxi-xxii)

As if to preview a French connection, Annette Hope frames the cover of A Caledonian Feast , her heartfelt evocation of Scottish history through the nation’s foodways, with a quartet of fleur de lis. To be fair, she does issue the warning that “early French intervention in our kitchens, like the Auld Alliance itself, was patchy, intermittent, unevenly distributed, and very much restricted to the upper classes.” (Hope 281)

She goes on, however, to try and make the case for an eventual French influence on Scottish practice, but the argument is labored and Hope does not really display much courage for this particular conviction.

The notion that early modern French contacts distinguish Scots from English cooking is difficult to credit, when French cooking also was driving inroads into the English kitchen at the time.

Hope does identify a number of Scottish food terms derived from the French that have not been used in England (‘gigot’ remains a usage for lamb in Scotland), but as in Louisiana (anduoille, boudin) these are French terms for products or dishes, not French-inspired products or dishes. The names of other Scottish recipes and ingredients may also derive from French sources but the dishes themselves do not.

A modern chief cousin.

To her immense credit Hope discloses manuscripts and publications that damage her brief, along with an engaging eighteenth century anecdote. Foul weather and a knackered horse stranded a French chef in the service of a Scottish general outside Edinburgh. A hospitable laird found him on the road and sheltered him from the storm. “The honest laird,” who knew no French, “seized upon the expression ‘chef de cuisine’, which he translated to himself as chief cousin, or first cousin” to the officer, a “good friend and neighbor.”

Misunderstanding became the mother of acquaintance. “Refreshments were produced, and the bewildered Frenchman was introduced to the ladies in the drawing-room as their neighbour’s cousin.” In the morning,

“after indulging in a hearty Scottish breakfast, he rose to continue his journey, but to his further astonishment, he found the laird’s own carriage waiting to convey him to his ‘cousin’s’ residence.” (Hope 296 quoting Ainslie)

Unlike the general, the hospitable laird for one lacked any acquaintance with French mores, culinary or otherwise. After reading Hope’s section of some fifteen pages on the subject in A Caledonian Feast , it is easier to conclude with Brears that any significant transmission of French culinary ways to Scotland reached only as far as the kitchens of magnates, did so through printed English sources, and then at only a few of the great estates.

Citing two trustworthy sources, Mrs, Johnstone and Eliza Acton, Hope herself concludes that any such influence differentiating Scots from English practice was short-lived as well as societally shallow. “The 19th century saw a gradual merging of Scots and English cookery,” at least in terms of French influence, “until they are undifferentiated in the recipe books.” (Hope 295)

As the century wore on, both countries became increasingly Francophile in culinary terms and most of the middling sort considered anything French, especially a private chef, “the height of sophistication.” Much that was considered French by the Victorian British, however, was not, and neither Mrs. Johnstone nor Miss Acton equated the fashion with quality. Any French cultural influence “was all at a superficial level.” (Hope 295)

That, it appears, always had been the case. In attempting to determine how Scottish foodways diverged from the English pattern, it is necessary instead to consider the climate, crops and conditions north of the Border, and most of all the Scots themselves.

Sources:

P. B. Ainslie, Reminiscences of a Scottish Gentleman (London 1861)

Alan Davidson, The Oxford Companion to Food (Oxford 1999)

Peter Brears, “Introduction” to Elizabeth Cleland, A New and easy Method of Cookery (orig. publ. Edinburgh 1755; Prospect Books facsimile Totnes, Devon 2005

Annette Hope, A Caledonian Feast (London 1987)

Hamish Whyte (ed.), Lady Castlehill’s Receipt Book: A Selection of 18th Century Scottish Fare (Glasgow 1976)