The unexpected origin of Shepherds’ pie.

It is a homely thing in one or another sense of the word, depending on your point of view. The coziest comfort on a wintry night, shepherds’ pie in different guise looms ugly along with sadistic classmates and hungry vampires in the nightmares of old English schoolboys or graduates of American boarding schools. Comfort comes from fresh ingredients selected for the very purpose of assembling the pie: The resort to manky leftovers can create bad dreams.

Shepherds’ pie is made from ground lamb ( not beef; that would be cottage pie) and winter vegetables seasoned in the British style, then baked under a potato topping. It is a cheap and simple dish.

It is a good one as well. They serve it at the Ivy in London, haunt of the wealthy and celebrated, but then they would; nursery food shares the menu with more ambitious offerings. Not just habitués of the Ivy share the conceit. According to Glyn Lloyd-Hughes, who has cataloged over 3,000 dishes in The Foods of England , “Tory grandee Jeffrey Archer was noted for serving shepherd’s pie and Krug champagne at his receptions.” (Lloyd-Hughes 107) Our own Bob Brooks, fastidious about his food, serves up his version laced with Worcestershire at raucous dinner parties featuring Labour luminaries and visitors from abroad. In Caledonian style he drinks Claret instead of Champagne with his pie.

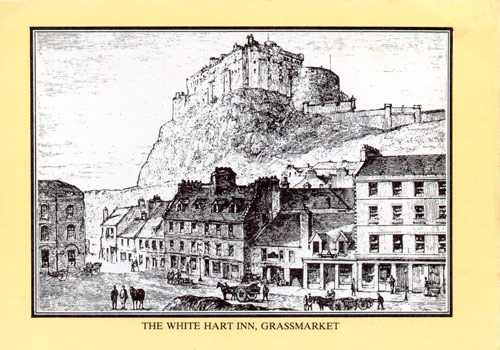

This last is a genuine manifestation of the Auld Alliance, for by the seventeenth century Scottish merchants had become prominent traders in Bordeaux. They kept watch on the vineyards from their outposts in the city, transshipping great quantities of wine through their vast warehouses in Leith, the port of Edinburgh.

To return to shepherds’ pie, its source remains mostly unexamined despite its ubiquity on both sides of the Atlantic. Lloyd-Hughes represents a lonely outlier, one of the few writers to address the origin of the dish. He betrays no compunction about claiming haggis, Scotch eggs and other reputedly Scottish dishes for England. In contrast, he ascribes the origin of shepherds’ pie, routinely associated with England and ignored by nearly all Scottish authors for over four centuries, to a book from 1854. It is The Practice of Cookery and Pastry by a Mrs. I. Williamson and was printed in Edinburgh.

According to the capsule history that Lloyd-Hughes has written, shepherds’ pie disappears “before about 1920 when it begins to appear in USA cookbooks, sometimes with potato underneath, or the top only partly covered.” Lloyd-Hughes agrees with The Oxford English Dictionary “ that mention cannot be found in England of Shepherd’s Pie before the 1960s.” (Lloyd-Hughes 107)

Things then get a little confusing, when he goes on to say that a “slightly later version” appears in Kettner’s Book of the Table , ghostwritten by the rakish and troubled E. S. Dallas: It was published in London during 1877. (Lloyd-Hughes 107)

E. S. Dallas

The confusion may be more apparent than real, due to a careless patch of prose by Lloyd-Hughes. He might have explained that Dallas compared the pie, which he did not much like, to Irish stew, and confined its presence to the Celtic fringe: “In Scotland they produce exactly such a stew, cover it over with a crust, and call it shepherd’s pie.” (Lloyd-Hughes 107)

In any event, Lloyd-Hughes and the OED are wrong. Elizabeth Craig for one leads her section of “Left-Over Meat Dishes” from the 1939 edition of Cooking With Elizabeth Craig with cottage pie, cross-referenced in her index as shepherd’s pie. The book first was published in London seven years earlier and became a bestseller in Britain for the next thirty years. Her recipe, based on leftovers and plain to the point of poverty, is not particularly appealing.

Craig was a Scot who spent her adult life in England but chose not to place a recipe for shepherds’ pie in The Scottish Cookery Book: The Classic Guide to All Things Best in Scottish Fare , which first appeared, also in London, in 1956. So she did not consider the pie Scottish at all.

Nearly no other references appear in Scotland, but in 1932, the anonymous author of The Edinburgh Book of Plain Cookery Recipes does include a shepherds’ pie that also calls for leftovers like the one from the perennially frugal Craig. The Practice of Cookery follows suit if, temporally at least, in reverse.

Its publisher found enough demand to run The Practice of Cookery through multiple editions all the way into the twentieth century. In a remarkable if predictable turn, it has become nearly impossible to find outside a handful of research libraries or in traduced and unreliable ‘print on demand’ versions.

The Editor’s fifth edition from 1862 is a mess, badly rebound, foxed and tattered, but serviceable enough all the same and its recipe for shepherds’ pie is unchanged from 1854. In it, Mrs. Williamson does not recognize the modern distinction between shepherds’ and cottage pie. Instead she is willing to use “cold dressed meat of any kind, roast or boiled” and sliced. She breaks the bones from the meat to make something like a rich demi glace;

“put them on with a little boiling water, and a little salt, boil them until you have extracted all the strength from them, and reduce it to very little, and strain it.” (Williamson 77)

Meat and stock get a dose of mushroom ketchup, some salt and pepper, nothing more, under their blanket of mashed potato. This is simplicity that sings to the essence of lamb, which is the meat you should choose for this pie.

Mrs. Williamson does not identify shepherds’ pie as Scottish but that omission should not deter anyone from considering it such. She does not identify much of anything else (only collops, haggis and pancakes) as Scottish either, including recognizably Scots creations like oatmeal pudding, which is actually sausage; she includes an instruction in the recipe to ‘fill the skins’ with her seasoned oatmeal mixture. It would appear that the practical Mrs. Williamson was no lyrical nationalist like Isobel Christian Johnstone some three decades earlier, although the two women may have shared a first name.

If The Practice of Cookery is forgotten, cookbooks more generally are not. In this age of unskilled cooks and convenience food, culinary voyeurism on the screen as well as on the page consumes the United Kingdom and the United States. Books for ‘cooks’ represent one of the dwindling categories that publishers consider strong.

Most successful cookbooks try to play on the aspirations of their readers. Anything written by a celebrity chef, especially one with a television tie-in, is a pretty safe bet. So, it seems, is shepherds’ pie. Celebrities like Tom Parker Bowles, famous chefs from Gary Rhodes to Tom Aikens in Britain, and Alton Brown to Emeril Lagasse in America, have published their own takes on the humble classic.

These figures are English and American, not Scots, and modern Scottish writers including Catherine Brown, Sue Lawrence and Christopher Trotter neglect shepherds’ pie. It is the reverse of haggis, something originally Scottish that has become associated with England instead. Each dish is something of an emblem of the Union.

Shepherds’ pie ought to cast a British if not Caledonian spell so it is bizarre of Parker Bowles to go all Cosmopolitan on it with red onion, olive oil and Thai chilies. Then again the Editor’s clipping of the recipe has been torn from a long lost glossy womens’ magazine.

Maybe the worldly Parker Bowles cannot help himself. Talk about an aspirational avatar for the social set; he is the Dutchess of Cornwall’s son, and so stepson to the Prince of Wales, was educated at Eton and Oxford, and has traveled the world “in search of culinary extremes.” Whether or not you agree with Goldwater that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice, it has no place in shepherds’ pie.

Rhodes tends to overwork his food to little purpose. The recipe for shepherds’ pie he has posted with the BBC, at once timorous and overwrought, is no exception. You must keep the ground lamb in lumps, or ‘nuggets:’ “Do not break the meat down in the pan but allow it to retain nuggets to retain the juice.”

Try not to drown the pie. And where is my palette knife?

Miniscule amounts of incompatible seasonings--thyme, rosemary both fresh and ground, cinnamon--get drowned in three glasses of wine that you must allow to evaporate half a glass at a time. Both ketchup and tomato sauce, but not too much, and an undetectable dollop of Worcestershire also will swim unseen in your ‘veal jus ,’ which seems more than fussy for comfort food, to irrigate the pie. Then finish the potato top by smoothing it with a palette knife (!) making sure not to mix it with the mince before you “make shapes in the potato.” At least Rhodes has not reached for the blue dye to summon a saltire.

Most of the others are simpler than this, worn retreads patched with a gimmick ingredient, but not Aikens’. By the simple expedient of adding turnip to the lamb he has emphasized the Scottish cast of his pie. Better yet would be mashing the turnip with potato to top the pie with clapshot, essential twin to haggis as the national dish of Scots.

Of all people it is Martha Stewart, or more likely a minion toiling away in the depth of her imperious enterprise, who has in fact stumbled upon the idea with a recipe from The Martha Stewart Living Cookbook in 2000 . It has good and bad points. On the positive side the recipe avoids extraneous abominations like corn and peas often added to the pie by other American recipes. On the negative side the recipe calls for beef as an option, as we have seen an inauthentic interloper, and does not mince the meat. In fact the recipe omits any instruction to do anything at all with its two pounds of meat, an editing oversight because back in 1994 the Stewart website included the instruction to cut the meat into one inch pieces.

In case anyone wonders, Stewart is not drawn to the Scottish through ethnicity. Despite the connotation of the name, her ancestry is Polish, which may or may not explain her affiliation with Kmart.

The best recipes for shepherds’ pie keep things simple and season the dish with abandon. If using an herb stick to one and choose a lot of it; use up your Worcestershire; load the clapshot topping with shards of shredded Cheddar. Forego false finery and choose the britishfoodinamerica pie indebted to Mr. Brooks.

Sources:

Peter Brears, “Introduction” to Elizabeth Cleland, A New and Easy Method of Cookery (Edinburgh 1755; Prospect Books facsimile Totnes, Devon 2005)

Elizabeth Craig, Cooking with Elizabeth Craig (London 1939)

Elizabeth Craig, The Scottish Cookery Book (London 1956)

E. S. Dallas, Kettner’s Book of the Table (London 1977)

Glyn Lloyd-Hughes, The Foods of England (Adlington, England 2010)

Martha Stewart, The Martha Stewart Living Cookbook (New York 2000)

Mrs. I. Williamson, The Practice of Cookery and Pastry (Edinburgh 1862)