Christmas Day

Thanksgiving is a good day in the kitchen, especially if yours has a television, because feasting with friends and family is the whole point of the holiday. What diversions the day offers in the form of parades, dog show and football do nothing to distract or derail the cook. You have time and, for better or worse, lots of eager helpers.

Christmas, however, is different. Christmas can be a stressful day for the cook, especially if you have small children opening lots of presents and impatient elders requiring your rapt attention. You may have spent all night assembling a bicycle or toy and if that is the case probably are hungover. The keys on the day therefore are simplicity and foresight tethered to create a kind of culinary masque worthy even of Inigo Jones and John Vanbrugh had they been cooks.

Lunch is a snap because you either have purchased some smoked salmon and brown bread for service with capers and lemon, or have taken the advice of the Editor and had prepared spiced beef, a laudable if lapsed holiday tradition, a week before the big day. Crusty bread, a few greens and some pickled walnuts complete this second lunchtime option. Whichever one you choose, drink Black Velvet but remember at any cost to pour the Champagne before the Guinness or you will get a Vesuvial eruption from your glass. You might tie a string around your finger in the mode of It’s a Wonderful Life but succeed where Uncle Billy failed by limiting yourself to a single digit.

Starters for dinner present no problem either. Terrines taste good with Champagne, a Christmas standby. They may be prepared a few days in advance and if anything their flavor improves from a little time in the fridge. Good English versions include the traditional marbled veal; an innovative combination of smoked haddock and shrimp from the peerless Phillipa Davenport; and our own terrine of oxtail. At a pinch you could buy something from D’Artagnan or Les Trois Petits Cochon, which do not sound English but might fool your guests (toss the packaging in advance).

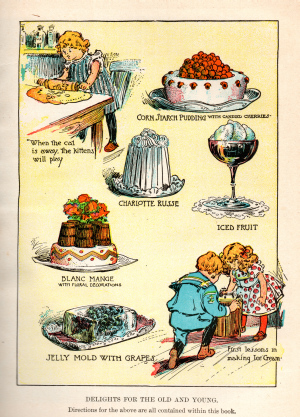

Dessert is easy too; our own bfia plum pudding is another advance job, and if you prefer a richer, fruitier version, presentable ones from Crosse & Blackwell that you can microwave in minutes appear on the holiday shelves at King’s and other upscale grocers along with festive little sixpacks of mince tarts from Walker’s, the oatcake and shortbread people.

Finish the evening with oatcakes and the sharpest Cheddar you can afford, some true Colston Basset Stilton and a few glasses of Port or India Pale Ale from an American brewer; Dogfish Head Sixty Minute, Lake Placid, Sierra Nevada Torpedo, Trinity and Victory Hop Devil vie most respectably for your dollar or pound.

Dinner itself is the dilemma. In the circumstances, a traditional roast turkey becomes a chore. It not only demands tending and takes some time, both to prepare and to cook, but also chooses when it decides to be done. No two birds are alike so you cannot hew to a rigid schedule which can get troublesome, just as your elders do after indulging in too much drink while waiting around for their food.

Compounding these problems, you may attempt a turkey only once a year so you are rusty and lacking confidence. In addition, you likely had started from behind given all the rituals of the day. There is not much margin for error either; with a roast turkey, minutes make the difference between succulence and sawdust. Roast beef is not much better; the preparation may be less arduous, and should occur on Christmas Eve, but a few minutes timing also makes the difference, in the case of beef between rosy meat and something grey.

A sturdy stew like Beef Guinness that you can prepare before the exhausting festivities therefore tantalizes the Christmas cook. Ham is never bad, and a devilled and roast shoulder of pork is amiably forgiving. The pull of tradition, however, is strong, for as the song goes, a turkey and some mistletoe help to make the season bright. It is the annual cook’s conundrum.

An agreeable expedient is to hand if only we are willing to consult the foodways of tradition, which makes pedagogical as well as pragmatic sense on this most traditional day. You must do what our English forebears did and boil your turkey.

The Editor understands that this proposal will sound radical, if not revolting, to many Americans. A vision of insipid and stringy grey gunk blots the mind. It is a mirage. Boiled, more properly simmered, turkey is tender and tasty, and to many palates superior to the roasted kind. In culinary terms, the pros and cons of each technique balance in equilibrium. You will not get crispy and addictive bronze skin from a boiled turkey; you will not get skin at all, you need to throw it away. There will not be pan drippings and therefore you will have no gravy. You will, however, have sublime oyster dressing, delicate celery sauce inflected with the shellfish and perfect meat. There will be poached salt pork to accent your bird and you will get a bonus in stock for a spectacular gumbo or soup.

As usual, however, we digress. The attraction of a boiled Christmas turkey is logistical. It does not take much time and is as forgiving as the pork. If your simmer hits a boil your turkey still will be fine. If you leave it too long, you have not harmed it, within reason of course. If it should cook faster than you want, let it steep in its liquor until you want it. Bring it back to a simmer and you are ready to go. You can extract the tithe of stock needed for celery or even oyster sauce ahead of time to eliminate the service scramble that inevitably characterizes a roasted bird and its trimmings. Mash some potatoes and serve something green and easy like bfia Brussels sprout salad or beans seared with bacon. A dryish Pinot Gris from either Alsace or the Pacific Northwest was born, or rather invented, just for all this.

oyster sauce ahead of time to eliminate the service scramble that inevitably characterizes a roasted bird and its trimmings. Mash some potatoes and serve something green and easy like bfia Brussels sprout salad or beans seared with bacon. A dryish Pinot Gris from either Alsace or the Pacific Northwest was born, or rather invented, just for all this.

It is Christmas and you are calm, perhaps almost happy. Your guests marvel, first at the novelty and then at your food. Triumph is upon you.

As we have inferred, the boiling of turkey once was no secret. In 1932, Florence White published her recipe for turkey made “Yorkshire Fashion” by replacing the breastbone with cooked tongue and boiling the hybrid stuffed with any “delicate well-made forcemeat.” She offers an entire catalog of “Rules for Stuffings and Forcemeat Balls” from an 1823 manuscript; “[p]arboiled sweetbreads and tongues are the principal ingredients” for all of them and some fifty-seven additions, alone or in various combinations as appropriate, make the supplemental list. (Good Things 184, 125-26)

Jane Grigson calls boiled turkey with celery sauce a “favorite dish of the Victorians and quite rightly so, because it is delicious--mild without insipidity.” (English Food 203) Her version simply simmers the bird upside down with aromatics of carrot, celery, onion, parsley and turnip seasoned with salt, pepper, bay and thyme.

The Reform Club chef and reformer Alexis Soyer, one of those Victorians, served his family boiled turkey for Christmas dinner. He cooked his turkey with herbs too, along with celery and onions, but added salt pork instead of the other aromatics to enrich its stock. His sauce, of celery and onion, uses the vegetables and stock that they made, thickened with a simple roux and some milk. As he wrote during 1854, “[a] turkey done in this way is delicious.” (Soyer’s Cookery 34) A light pasta soup made from the turkey stock, baked potatoes and a plum pudding rounded out the Soyer family’s holiday feast.

Neither Mrs. Grigson nor the great Soyer stuffed their boiled turkey with oyster dressing. Based on our research that puts them in the minority, for the bird and bivalve have been inextricably linked in the English tradition. In 1783 the hacks who wrote The London Art of Cookery attributed to John Farley, proprietor of the London Tavern renowned throughout Europe for its food, instructed their readers to

“grate a penny loaf, chop fine a score of oysters at least, shred a little lemon peel, and put in a sufficient quantity of salt, pepper and nutmeg. Mix these up into a light forcemeat, with a quarter of a pound of butter, three eggs, a spoonful or two of cream, and stuff the craw with it; the rest must be made into balls, and boiled.” (London Art 40)

This recipe makes a subtle stuffing that will taste lighter if you substitute shredded suet for the butter; either way the forcemeat balls may be simmered along with the turkey itself. Farley served oyster sauce with turkey and garnished it with barberries and lemon.

The iconic Art of Cookery Made Plain & Easy from 1747 by Hannah Glasse lists five recipes for stewed turkey, including a souse and an intriguing preparation that involves broth, celery, an undisclosed kind of ketchup, mace and red wine.

In the ‘best for last’ category stands our own customized recipe from britishfoodinamerica; it appears in the practical. We have borrowed and stolen elements from the older preparations to create a foolproof and harmonious whole. It is just what you wanted for Christmas.

Recipes for baked and boiled fresh ham, two festive terrines, boiled turkey, Cumberland sauce and a 17th century mustard sauce can be found in this number’s the practical. Recipes for spiced beef, Brussels sprout salad and autumn (plum) pudding can be found in our archive.

Confessional postscript:

The Editor likes to cook and eat boiled turkey so much that she bends tradition to serve one, alongside a roasted bird, on Thanksgiving too.

Sources:

‘John Farley,’ The London Art of Cookery (London 1783)

Hannah Glasse, The Art of Cookery Made Plain & Easy

(London 1747)

Jane Grigson, English Food(London 1974)

Alexis Soyer, A Shilling Cookery for the People, Embracing

an Entirely New System of Plain Cookery and Domestic

Economy (London 1854)

Florence White, Good Things in England (London 1932)