More notes on potted foods, this time toward the onset of winter.

As winter looms, our thoughts have returned to traditional means of preserving foods. One of the oldest English techniques involves potting pulverized food, usually but not always proteins, under a protective cap of clarified butter.

As we observed back in bfia Number 25, you can pot just about anything. The Master Book of Fish by Henry Smith from the mid-1940s has recipes for potted carp as well as lamprey. To prepare the lamprey you first would need to “free them from slime” and then bake the suckers with beef dripping before they are suitable to pot. As this charming anecdote might indicate, the topic of potting is a potential evergreen for the food writer.

1. A welcome new Company that Pots Game.

In these days of revived interest about traditional British foodways, at least in Britain if not the United States, at least not yet, you no longer need to make your own pots. Alone among potted foods, shrimp never disappeared and has been available storebought from a number of good producers in the United Kingdom without interruption. Now, however, the Potted Game Company also offers a number of other potted foods at a fair price.

For centuries, British cooks have (or, until recently, had) potted any number of ingredients to preserve them but the Potted Game Company itself dates only to 2011. It is a small operation run by its two founders, Rory Baxter and Jemima Palmer-Tomkinson, who both have worked as private chefs to the wealthy. They operate out of Gloucestershire, and so far only four shops, all of them in the pretty Cotwolds, currently stock their pots.

The company also has regular stalls at the peerless Borough Market in London, where the Editor purchased her pots, and at the Stroud Farmers Market where our own Charles Burling, sometime compiler of Notes From the Edge (of the Forest of Dean) has been spotted shopping with some frequency.

Baxter and Palmer-Tomkinson currently produce six pots (we also have seen pictures of a seventh, grouse, which must be seasonal) and sell four of them online. We have tried two, a potted pheasant with bacon and hazelnuts, and rabbit with cider and mustard. These are fresh products packed in little plastic tubs, preserved only in a fleeting sense; shelf life is no more than a couple of weeks.

The pheasant holds lots of well-spiced and yet delicate gamey flavor but was, as pheasant can be, a little dry. That is not the end of the proverbial world, however, and it is painful to fault these cooks who do not scrimp on expensive meat (between bird and bacon 71% of the pot; the nuts account for another six) or overcharge. Each little 65 gram (roughly 3 oz) pot costs £3.50, excellent value for money if not actually cheap.

We are happy to report that we have virtually nothing to say about the rabbit. It was faultless, even flawless and we wished for more. We are sad to report that none of the Company’s potted crayfish [sic] with cayenne and mace (so traditional!) was available during the Editor’s visits to Borough Market.

No shipping outside the United Kingdom so Americans must visit to taste their pots.

2. Potted duck from Canteen.

A recent starter of potted duck at Canteen in Spitalfields was so good that the Editor decided to try her hand at a variation on the recipe, one of three that appears in a booklet the proprietors place on each table at all four of their London locations. It is a handsome little publican, as we should expect; a design team owns the Canteens and it shows. It must cost them a relative bomb; stock is hefty, production values high and it runs to 32 pages. This is promotional material to be sure, but it is an interesting promotion, provides information about ‘What to do close by’ each of the restaurants and includes those recipes.

They gain an advantage from starting their potted duck from scratch, because frugality moved the Editor to use the legs from a good roast. Canteen braises the duck for its pot with ale, bay, garlic and sage, which adds a lovely layer of flavor to the finished pot; the Editor’s duck tasted a tinge of bacon, which covered her (duck’s) breast in a hot oven; not bad either. What makes the Canteen pot, however, is the finish; they mash it with Madeira and mace and so did we; sublime.

3. A related digression on ‘mechanically separated chicken.’

‘Pink slime’ has been much in the news because people finally tumbled to the fact that the food we routinely serve children in the United States is loaded with the stuff. Mechanically separated chicken, or ‘white slime,’ is the same thing, made with poultry instead of meat.

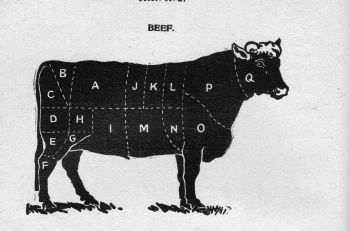

This is the kind of substance that could be created only by the bottom line: Nobody who cares about food possibly would have dreamed it up. If you assume that the terms ‘chicken’ and ‘meat’ are synonymous in terms of what you eat then ‘mechanically separated chicken’ is utterly deceptive. It includes connective tissue--ligaments and tendon--marrow, fat, skin, bits of bone and a few scraps of meat.

Whence the slime?

To make the slime, for that is what it is, the carcass stripped of breast, legs, thighs and wings is crushed and, together with skin, rammed through a sieve under extremely high pressure. Jamie Oliver has described the result as “hideous and disgusting.” It is no exaggeration: As one website observes, foods containing white slime literally are “[m]ade by, for and with assholes.” (www.thesneeze.com)

A similar substance, “partially defatted fatty tissue,” is created from cows or pigs (we explicitly refrain from using ‘beef’ or ‘pork’) by a different process. The Code of Federal Regulations defines the slime created from pigs as “[f]resh pork fatty tissue, excluding skin, that has been rendered at a temperature not more than 120 degrees Fahrenheit and is pinkish, fresh-looking and tasting.” Again, not very nice.

It is not that we object to butcher’s cuts, offcuts or offal; we relish them all, but these edible industrial artifacts are not that. They are dangerous vessels of cholesterol and fat that are devoid of taste, so the factories juice them with artificial flavorings, sugar and salt.

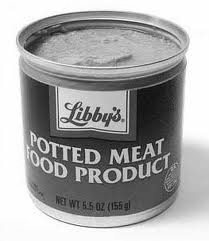

4. An American abomination: Commercial ‘potted meats’ to avoid…

This section requires an immediate warning and disclaimer: The products described are not recommended. All of them are called potted meat, all of them come in cans and none of them has the faintest connection to a potted food that would be familiar to anybody, English or American, from the eighteenth century. And if this is what contemporary Americans think when they think of potted meat, then it is scant wonder that British food remains a tough sell across broad swathes of the population.

Armour, Brunswick, Bryan, Hormel, Ralph’s and other soulless companies sell ‘potted meat’ in the United States. All of them are cheap, 59¢ or so for a little can, and bad. The Food and Drug Administration requires them and everyone else to post the ingredients of any product in descending proportion on the label, but it is easy to subvert the rule.

Armour Potted Meat, for example, lists our ‘mechanically separated chicken’ first, followed by tripe, salt and spice, so like the pheasant from the Potted Game Company the substance is composed predominantly of two ingredients. There all similarity ceases. We might believe that the Armour product is primarily made from meat but it is not. Of the 120 calories per serving, 80 come from fat. Tripe is not at all fatty, so that mechanically separated chicken is schmaltz, and Armour Potted Meat is in fact a can of gushy pink fat masquerading as something less deadly. At least Armour no longer includes partially defatted fatty tissue in its potted meat; other factories do.

Some unhealthy foods taste pretty good but not any of these. The texture is predictably unpleasant, the color foul and the flavor… actually the flavor is nearly nonexistent but for its salt. There is no reason other than grating poverty or sheer perversity for eating these things unless you are deficient in cholesterol, sodium or saturated fats.

This is no elitist rant. Cheap canned products can be good. Anchovies and sardines are good food, so are canned beans and the Editor has a demonstrated fondness for the guilty pleasure of Underwood Devilled Ham, which includes nothing mechanically separated or partially defatted and provides the tasty base for a quickly potted food, as we noted in Number 25.

5 …but it is not hard for anybody British or American to make their own good pots.

With a food processer, blender or Old School meat grinder it is easy to make potted foods; fun too, if you like that sort of thing, and we do. As an added benefit they last for weeks refrigerated under their essential clarified buttercap, which allows you to make a big batch for later eating.

Preservation of course was a potted food’s most important characteristic before the 1920s and not just for dainties. Cooks even would pot whole birds in big crocks for keeping over the bleak winter months or a long voyage at sea. Pots did excellent duty onboard ship by breaking the monotony of salt food although, a bit of a surprise, we do not find potted items in Royal Navy inventories from the age of fighting sail.

6. Pots at sea.

That is not the case for civilians. In her eccentric and indispensible Food of England, first published in London during 1954 and now available in a new edition, Dorothy Hartley makes a case that potting originated as a technique for concentrating as well as preserving foodstuffs for consumption at sea. “As to the medieval custom of killing stock before winter we owe our knowledge of salting and curing,” she contends, “so to the early sailing ships we owe our knowledge of potted and dried meats.” (Hartley 345)

The Editor has not encountered the assertion elsewhere, so it may be worthwhile considering Hartley’s evidence. She explains that an aunt of hers “was one of the first women travelling to the West Indies in sailing ships” and ate potted foods onboard, but provides no date for the transit. Much of the shipboard food does not help to set the time; the live animals and preserves, the dried, potted and salt foods that the aunt describes could have been carried at any time from the seventeenth through the nineteenth century, but there are clues.

A diagram for ‘close-packing’ chicken, another preservation technique, bears the somewhat curious legend “Export 1890.” Even though the aunt was no exporter, at least as we understand the term, and as Hartley uses it elsewhere in the same chapter, she claims that the aunt drew the picture. In fact, however, it shows the hand of the same artist who gave Food in England all of its illustrations.

The aunt, who “had the minute memory and zestful interest of her period,” was not a settler; “she remembered voyages of several months’ duration.” Note the plural usage; the aunt went back and forth.

She and other passengers on these trips shipped “watercress growing in jars” in addition to the preserved foods, which implies knowledge of its prophylactic effect as an antiscorbutic. They also dined at the captain’s table, so we likely are dealing with sometime in about the middle of the nineteenth century, and Hartley provides a further clue when she cites a technique for potting ducks.

It was used by an aunt of Hartley’s, but whether or not she is the same woman as the one discussed in a different section of Food in England is undisclosed. Despite the uncertainty, this reference provides considerably more support for her theory that pots arose from seaboard necessity, because Hartley reproduces the “sixteenth century recipe for shipboard storage” that the aunt used to make the potted ducks she brought with her on a voyage to West Africa in about 1850. (Hartley 343)

Preservation may have been essential but concentration was in itself useful because it saved valuable space and weight for cargo, passengers or other stores on land as well as at sea:

“The best parts of the meat were cooked in the pots; it was essentially a condensing process used to compress extra food value for seamen and travellers--and it is significant that the luxury potted meats, the luxury potted salmon, potted hare, and so forth, are still found around the old sea-port towns and posting inns.” (Hartley 347)

For some reason chemical or alchemical, the process of potting concentrates flavors as well as dimensions and nutrients, so that pots will impress any guest at your table with their rich intensity.

Hartley made the observation about potted foods at seaports and inns in 1954; by the 1970s it no longer held true, although the circle is turning once again. In New Orleans, to cite a single example, the recently opened R’evolution includes a section of ‘potted meats’ on its extensive dinner menu. The restaurant is the creation of John Folse, author as well as chef and authority on the evolution of Louisiana foodways. Folse likes to cite the ‘seven nations’ that have contributed to the creation of the state’s distinctive cuisine: England is one of them.

On the question whether the historical impetus behind English potted foods is maritime or landed, however, the proverbial jury remains in deadlock.

7. Pots past and present.

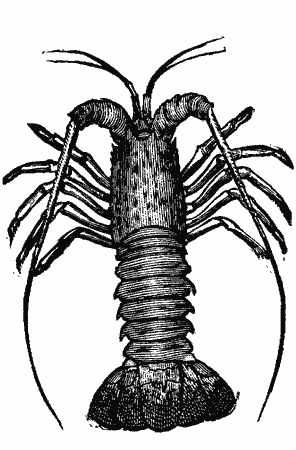

Potted foods that we have produced since Number 25 other than Canteen duck include bluefish (in a recipe for mackerel; the fish are interchangeable), crab, crawfish, lobster and scallop.

The lobster recipe arrives at britishfoodinamerica from the redoubtable Elisabeth Ayrton via a manuscript compiled in Reading (England) during 1760. As she points out in The Cookery of England (London 1975) it and other recipes from the compilation “are quite clear and specific and need no translation or annotation, and are… very good indeed…. ” (Cookery 147) See for yourself:

“Boyle the lobsters till they come out of the shells then take the tailes and claws and season them with mace, salt and peper then put them into a pott and bake them with sweet butter and when they come out of the oven take them out of the pott and put them in a long pott and clarifie the butter they were baked in with as much more as will cover them very well and set them by for use.” (Cookery 147)

Miss Hartley does not confine herself to ocean voyages. Her discussion of potting more generally may be brief but is characteristically good. She offers her readers a number of traditional recipes, including one for ‘shrimp paste,’ a bit of a misnomer because the tiny shrimp go into the pots whole. This is a pot as much as any other, but gets its own name because the shellfish is set in a paste of butter and seasoned cod (cayenne, mace, anchovy sauce) instead of butter alone; a lightened pot from the 1800s for the fastidious twenty-first century diner.

That ‘paste’ in this context refers to a kind of pot is corroborated by other sources.

In her landmark article in the April 1965 number of Nova, “English Potted Meats and Fish Pastes,” (then three years later in pamphlet form and finally in the anthology of her essays, An Omelette and a Glass of Wine, during 1985), for example, Elizabeth David includes a recipe for ‘Salmon Paste’ that she describes as a “more ordinary version of potted salmon.” She has a recipe for the pot too, and for salmon butter. David also published recipes for sardine, smoked salmon and ‘tunny fish’ butters in “English Potted Meats.”

Not all fishy pots, however, become paste. The older sources cite potted crab and lobster but neither crustacean gets pasted or becomes butter either. This is simply another example of English idiosyncrasy; the culinary lexicon also makes a similar kind of exception for fish pie. Other pies case or top their fillings with crust, but not fish, which in common with shepherd’s and cottage pie gets a topper of potato instead.

Neither David nor, apparently, anyone else has addressed the reason why potted fish but not meat historically may be called a paste. Then again James Beard published recipes for beef paste during the 1960s, but his usage appears to have been descriptive rather than traditional, or coincidence instead of scholarship. With her customary lack of historical rigor, David does not address the origin of potting, much less the maritime theory.

As paraphrased by Miss Hartley, here is the recipe for shrimp paste, which belonged to a Betsy Tatterstall who served it for “Shrimp Teas” during the early twentieth century at her little house in the North of England. It is hardly an ‘ordinary’ alternative to potted shrimp but rather more complex and completely delightful.

“Weigh the shrimps, and take an equal quantity of fine flaked white fish. Shell the shrimps, and put heads and shells to boil in enough water to cover. Drain, remove the shells and heads, and now cook the flaked fish in this shrimp water till soft. Let it cool, and pound to a smooth paste with a careful seasoning of powdered mace, cayenne and one single spot of anchovy sauce. Now measure, and add an almost equal quantity of butter. When smooth, stir in all the whole shrimps, make all piping hot, press into pots, and flood with melted butter on top.

The effect was a solid potful of shrimps, cemented together with a soft, delicately seasoned pink butter.” (Hartley 282-83)

Shrimp heads will do that.

8. Perfidious France.

In Number 25 we remarked on the dearth of British recipes for potted liver, and found it strange that we then had found only one. Mrs. Ayrton, however, has two more, each for some reason disguised as pate. It is an odd affectation for so meticulous a writer, for as she herself points out:

“The French word pate means ‘paste’: in fact the meats concerned have been reduced to the consistency of a paste. The English equivalent is potted meat: meaning that meats have been reduced to a form convenient for keeping in a pot; i.e. to a ‘paste’”. (Cookery 125)

Plus ca change; as with Crème Brulee, the French once again have been getting credit for things not at all theirs, and have been abetted by an ordinarily reliable author. So, as Mr. Vonnegut said, it goes.

Recipes for potted duck, liver, lobster, salmon and scallops, along with shrimp paste and sardine butter, which are really pots, appear in the practical.