Reflections on Snapper Soup: Philadelphia Preserves Old Foodways

1. The taste of Philadelphia.

No dish with the possible exception of pepperpot or perhaps scrapple shares a closer association with Philadelphia than snapper soup. The name is relatively recent but the soup itself is not, for the dish as we know it originates in the early eighteenth century City of London. No Lord Mayor’s Feast was complete without its centerpiece of turtle soup, the most potent signal of elegant dining during the ‘long eighteenth century’ from the Glorious Revolution until the ascent of Victoria.

2. Its English origin.

This was an archetypally English dish. According to Sharon Stallworth Nossiter, Escoffier observed that “[t]urtle soup is seldom appreciated in France and therefore rarely found on the menu.” The dearth of French historical sources for any recipe bears him out. Escoffier himself did include a detailed recipe for the soup in his Guide Culinaire, but then he was working in London at the time. (Tucker 93)

3. All the rage.

It did not take long for Philadelphians to acquire a taste for their own version of turtle soup. In general, the Quaker city looked to London as the “measure of good taste” in all things culinary as well as fashionable. (Larder 19) According to Mary Anne Hines et al.,

“turtle meat has been a highlight of Philadelphia’s cuisine since prerevolutionary days. Delicious soups were made from the large green sea turtles caught in the Atlantic and brought back by ships returning to port.” (Larder 50)

During the 1750s turtles “of a size it took a man to carry” abounded in the Philadelphia market, and John Adams recorded eating turtle soup a number of times while attending the First Continental Congress. (Schweitzer 39) It was so popular that taverns advertised the arrival of turtle meat in the newspapers; demand was so great that some places required diners to buy tickets in advance. (Larder 50)

Pass the soup.

Fanny Kemble, the English actress and celebrity, disliked “stewed oysters and terrapins” but could avoid neither dish in the Philadelphia of 1832, where she found them “the refreshments invariably handed round at an American evening party.” (Schweitzer 39)

It was this popularity and the short season when the big turtles appeared in the Caribbean that “led Philadelphians to the discovery of an economical substitute in the traditionally Black dish of terrapin. Terrapins were common marsh turtles found locally in the Delaware and Chesapeake Bays and while much smaller than their ocean-going counterparts, had much the same flavor. By the late 19th century ‘the bird’, as it was called, had moved from the realm of slave food to the highlight of most catered dinners and banquets.” (Larder 50) Rarity has accelerated toward near extinction to the point that since enactment of the Endangered Species Act in 1971 it is illegal in the United States to kill a sea turtle. Terrapin took Philadelphia by storm. During 1879 in his book The Epicure, Colonel John Forney claimed:

“Terrapin is essentially a Philadelphia dish. Baltimore delights in it, Washington eats it, New York knows it; but in Philadelphia it approaches a crime not to be passionately fond of it.” (Schweitzer 45

4. An excursion to Hoboken.

New York may have known turtle soup, but New Yorkers streamed across the Hudson to get it, at the Hoboken Turtle Club. Founded in 1796 as one of the first clubs of any kind in the United States, it cooked the many members and their guests turtle steaks as well as soup and survived for over a century.

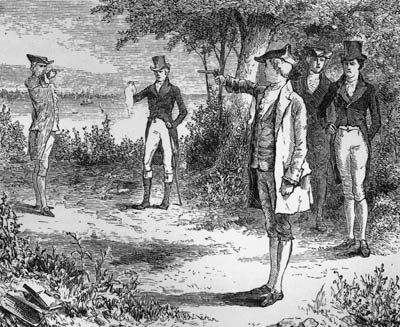

Early members of the turtle club included Burr, Hamilton and other luminaries from the revolutionary generation. (Schweitzer 39) “And,” according to E. B. White, “the middle ages had such names as Boss Tweed, Jim Fiske, Governor Sulzer, Colonel Ruppert, and George Bell they named Pelham after. All turtle-eaters.” (White 18)

Couldn’t we settle this amicably over soup at The Turtle Club?

5. A soup by any other name….

Turtle soup may not be quite so ubiquitous as once it was in eighteenth and nineteenth century Philadelphia, but the city has eclipsed London as its epicenter, and along with New Orleans wins credit as the keeper of this culinary flame. Today the dish has disappeared from British tables while it continues to flourish, if always in the guise of snapper soup, at any number of restaurants and clubs in Philadelphia. New Orleanians, however, never call it that. The evolution of the term ‘snapper soup’ as common usage in Philadelphia has received scant comment. According to Teagan Schweitzer, “recipes for snapper soup are, by and large, absent from cookbooks in the 18th and 19th centuries” even though snapping turtles were plentiful in Philadelphia at the time. While it would be more accurate to observe that the term ‘snapper’ was absent--recipes involving snapping turtle, terrapin, sea turtle and other species are interchangeable--Schweitzer is right to point out that snappers, “for whatever reason, did not receive the same level of press as the other varieties.” (Schweitzer 43)

It would be logical enough to assume that ‘snapper soup’ became accepted usage after snapping turtle rather than one of its cousins became the featured ingredient, but unsupported assumptions can be dangerous and this one fits the pattern. Schweitzer’s “zooarchaeological data” indicates that during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, Philadelphian households most commonly chose snapping and box turtles (but never have referred to ‘box’ soup or otherwise specifically to the species) for making their soup, which incidentally Schweitzer speculates was a simpler affair than the recipes followed at taverns and banquets. That makes sense. Sea turtles were huge enough to be unmanageable in a domestic context and the era of the terrapin may not yet have begun. So the twentieth century usage of snapper soup, confined almost exclusively to Philadelphia, remains a puzzle.

Size matters.

6. The American scene.

Regardless of name, the soup as we still know it makes an early appearance in North American printed sources; in fact it appears in the first American cookbook, Amelia Simmons’ American Cookery, published in Hartford during 1797. Her recipe is elaborate, the longest in the book, but is less jarring to modern readers than other eighteenth century versions like the English one from Hannah Glasse. Hers is the first one that appears in print anywhere, but only in 1751, not in her first edition of 1747.

The recipe from Mrs. Glasse would have been familiar to Philadelphians. Eighteenth century books, including cookbooks with their recipes for turtle soup by her, ‘John Farley,’ Eliza Smith, William Verral and others, could reach Philadelphia bookstores within a month of their publication in London, and the New World city itself supported a robust printing industry. Philadelphia presses published their own editions of books by English authors, helping to maintain the English cast of the city’s cuisine until the great waves of nineteenth century immigration transformed so much of its popular culture.

Enter the English.

Not, however, that many people are likely to have prepared turtle soup at home after the early nineteenth century.

7. Arduous enterprises.

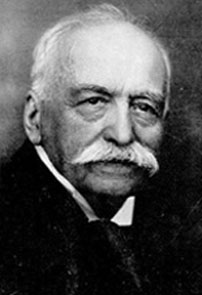

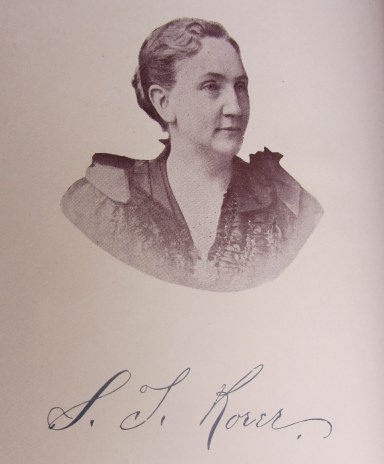

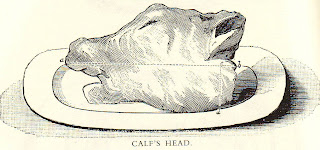

Despite its rampant popularity in her city at the time Sarah Tyson Rorer first published the influential Philadelphia Cook Book in 1886, turtle soup makes no appearance there. Mrs. Rorer does, however, include mock turtle soup, which takes a long time and a lot of ingredients to prepare.

The intrepid home cook would need to clean, dress and simmer a whole calf’s head (Mrs. Rorer recommends having “the butcher unjoint the jaws and take out the brains”), add heart, liver, vegetables and seasonings including those English standbys mushroom ketchup and Worcestershire, all in the service of approximating the texture and flavor of turtle. (Rorer 17) Why go to so such Byzantine lengths rather than reach for the real thing?

At first the absence of the traditional turtle from Mrs. Rorer’s treatise appears strange. And a treatise it is; the book runs to nearly six hundred pages, includes over a thousand recipes (some seventy-six of them soups) along with doses of stern domestic advice. She is considered the first American nutritionist, and subsequent authors like Margaret Yardley Potter found her preachy. Not that Mrs. Rorer lacks a certain style; we should at least hope that calling a recipe “Bouillon for Parties and Germans” evinces a sense of humor.

A preacher

Incidentally, Mrs. Potter includes a recipe for “IMITATION CLEAR GREEN TURTLE SOUP, and a fine one” in her own cookbook, published to no acclaim in 1947 but happily salvaged from obscurity by her granddaughter and reprinted with annotations this year. The soup leans heavily on canned consommé and includes only five other ingredients; hardboiled egg, lemon, parsley, dry Sherry and, surprise, avocado.

Mrs. Rorer and Mrs. Potter are typical of their times in their omission of recipes involving actual turtle, and a number of reasons account for its absence from most cookbooks then and now. Overfishing had rendered the economical terrapin rare and other species of turtle always have been expensive and so impractical to use as everyday ingredients. (Larder 50)

People like turtles, and if the idea of eating one is not so repulsive as cooking up Rover, it will not sit well with most contemporary Americans, or Britons either.

It is hard to dress a turtle. Eliza Leslie, the otherwise undaunted Philadelphian cookbook author of the mid-nineteenth century, offered her readers instructions for preparing mock turtle soup but not the “real” article because, she explained, “when that very expensive, complicated, and difficult dish is prepared in a private family, it is advisable to hire a first-rate cook for the express purpose.” (Nossiter 93; Schweitzer 39)

A sea turtle could weigh hundreds of pounds; in comparison a calf’s head, helpfully disjawed by the butcher, was convenience food. Once killed, the process of sorting the innards of the turtle was not without its complications, and not for the faint of heart. The descriptive instructions that Mrs. Glasse provides are nothing short of grisly.

The easier option.

A century and a half later, Escoffier observed that “[t]urtle soup is very rarely prepared in the kitchen of catering establishments. It is more generally obtained ready-made, either fresh or preserved….” He does, however, offer the ambitious reader a recipe for turtle (not ‘snapper’) soup “in the event of its being desirable to prepare it oneself.” His instructions for the ‘slaughtering and dismemberment’ of a turtle--“the simplest and most practical for the purpose”--are graphic, messy and involved. At that point we have not yet even arrived at the stove. No wonder that even this master of technique warned devotees of turtle soup that “it is best to buy it ready-made.” (Escoffier Cook Book 221)

Eliza Acton and Elisabeth Ayrton elaborated on Miss Leslie’s sentiment. Writing over a century apart (Acton in 1845; Ayrton in 1975), they each advise their readers not to attempt the soup at home due to the awkward and unpleasant process of butchering the live animals. A year after Mrs. Ayrton, Lizzie Boyd also omitted turtle soup, but without explanation, while including two recipes for mock turtle soup from the encyclopedic guide to British foodways that its publisher hoped would exert as much influence on the nation’s cooking as “‘Escoffier’ and ‘Larousse.’”

Sheila Hutchins, a contemporary of Mrs. Ayrton, was squeamish to the point of phobia about preparing turtle soup. In 1967, she described the process as ‘dreadful,’ ‘gruesome’ and ‘complicated.’ During the sixties, bottled and canned turtle soup that only required a cook to cut the meat into dice apparently was available in Britain and Hutchins advises cooks to use it. (English Recipes 38)

8. Back to the domestic kitchen.

There is an outlier. In 1999, Walter Staib, the proprietor of the historic City Tavern in Philadelphia, included a recipe for turtle soup in his cookbook (since recast with a few additional recipes and heavy doses of glossy food porn), but then Staib himself is a restaurateur and anyway skips the butchering process altogether in specifying “skinless and boned turtle meat.” He claims that this item “is sold fresh at some seafood stores” (maybe, but not at any the Editor has visited) “or it’s available frozen or canned.” (Staib 30) If the preserved stuff is not much in evidence at the typical brick and mortar, you can obtain turtle online, at sources including www.exoticmeatmarket.com and www.louisianabestseafood.com.

Turtles within…

To make a more than serviceable facsimile of turtle soup, you need not go to the expense and trouble of buying turtle or embark upon the earthy experience of wrestling a cow head. Gamier cuts of beef, like skirt, work fine.

Our recipe for ‘snapper’ soup made with beef that would fool a colonial Philadelphian duly appears in the practical. Margaret Yardley Potter’s recipe for clear mock turtle appears there too. It will not fool anybody but has genuine appeal; quick, easy, light and refreshing.

Sources:

Eliza Acton, Modern Cookery for Private Families (London 1845)

Elisabeth Ayrton, The Cookery of England (London 1975)

Auguste Escoffier, The Escoffier Cook Book (New York 1941)

Hannah Glasse, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (London 1751)

Mary Anne Hines, Gordon Marshall & William Woys Weaver, The Larder Invaded: Reflections on Three Centuries of Philadelphia Food and Drink (Philadelphia 1987)

Sheila Hutchins, English Recipes and others (London 1967)

Sharon Stallworth Nossiter, “Turtle Soup,” in Susan Tucker et al., New Orleans Cuisine: Fourteen Signature Dishes and their Histories (Oxford MS 2009)

Margaret Yardley Potter, At Home on the Range (San Francisco 2012)

Sarah Tyson Heston Rorer, Philadelphia Cook Book: A Manual of Home Economies (1886; Applewood Books facsimile, n.d. Bedford MA)

Teagan Schweitzer, “The Turtles of Philadelphia’s Culinary Past: An Historical and Zooarchaeological Approach to the Study of Turtle-based Foods in the City of Brotherly Love ca. 1750-1850,” Expedition vol. 51 no.3 (Winter 2009)

Walter Staib, City Tavern Cookbook: 200 Years of Classic Recipes from America’s First Gourmet Restaurant (Philadelphia 1999)

E. B. White, “Essenfest,” The New Yorker (3 October 931) 17-18