Saveur roasts six turkeys; we weigh in with two

1. American turkeys--or maybe not.

Each November, Saveur magazine runs an article about the best way to roast a turkey for Thanksgiving. This year’s is called “The Perfect Bird;” other headlines have included “How to Roast the Ultimate Thanksgiving Turkey,” “The Ultimate Turkey,” “Step-By-Step Guide to Perfect Roast Turkey” and another “Perfect Bird.”

Turkey matters. Thanksgiving is a favorite holiday and the subject is both dear and germane to britishfoodinamerica. The ‘first’ Thanksgiving at Plimoth was not, as Sandra Oliver points out in Giving Thanks (New York 2005), really a first at all, but rather an adherence to tradition. By 1620, harvest feasts already enjoyed a long history in England. The colonists clung to their English culture in food as in other things during the initial struggle to survive an unfamiliar climate, and turned to native crops like corn only after attempts to grow familiar grains like barley and wheat failed.

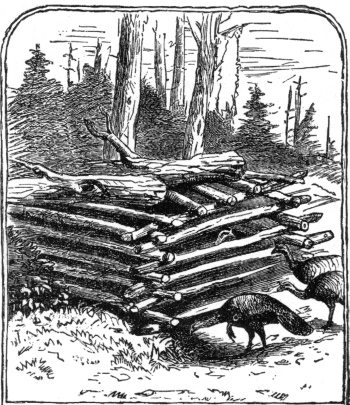

The settlers were familiar with domesticated turkeys and hunted their abundant wild cousins in New England. They brought no turkeys with them on the initial voyages, however, and may or may not have enjoyed wild ones at their first harvest table.

Contrary to common belief, domesticated turkeys would first arrive in North America from Britain. English poulterers had transformed the little birds imported from South America via Spain over a century before the first English settlements in the future United States. Norfolk turkeys had become prized as early as the seventeenth century, and drovers herded thousands of them on the roads to London for each Christmas season. The English breeds were bigger and hardier, the stocks from which North Americans would create their own distinctive turkeys, the bronze, buff and Narragansett among them.

2. Cooking the big bird…

Roasting a turkey was the technique of choice until the early nineteenth century, when boiling the bird enjoyed a vogue that would disappear in the twentieth. The Editor is an outlier; she boils one turkey and roasts another every Thanksgiving.

Saveur offers its readers a number of alternatives to roasting a turkey. The magazine’s contributors braise it with Riesling or mole; grill it; stew it with collards; pot roast drumsticks in beer; spice and tomatoes; deep fry it and more. This, however, is Thanksgiving so our immediate interest lies in roasting our turkey.

Does precedent matter to Saveur? In other words, has the magazine demonstrated consistency in the advice that it offers its readers? Saveur may be the most enjoyable of the mainstream food glossies, so here at britishfoodinamerica we decided arbitrarily to track the last six years of Thanksgiving articles in the magazine. All of the authors who published recipes disapprove of stuffing a turkey, three of them brine the bird and a fourth dry cures it overnight under salt. Otherwise we found a certain amount of variation.

3… is easy…

“The Centerpiece” from 2006 includes the unremarkable observation from Rita Williams that in her family “Thanksgiving prep always started with a shopping list” and a straightforward enough recipe for “Brined and Roasted Turkey.” (Saveur no. 97, 62, 64) It keeps the oven at a steady 325° and recommends removing the turkey once a thigh stabbed by a thermometer reaches 165°, while noting that others “cook their turkey to 175° or above,” which, we think, would destroy the white meat. (Saveur no. 97, 62)

4… or not?

The following year Saveur turned to the hosts of a radio program broadcast from Minnesota called “The Splendid Table.” Lynne Rossetto Kasper and Sally Swift present another recipe that uses a brine but otherwise bears no resemblance to the prior version. They must have hoped to earn a premium for novelty.

The radio hosts do not lack confidence. According to Swift, “[w]ith a scientific rigor that would impress Charles Darwin, Lynne has arrived at the definitive brine…, the definitive cooking temperature (higher than called for in most recipes, so the skin stays crisp and the flesh stays juicy) and the definitive pan gravy (made with stock, apple cider, and calvados for a richer foundation).” (Saveur no. 106, 68) We do not find out how Kasper got there, and no matter, but Darwin?

The 2006 recipe brines its turkey in a solution of salt and sugar flavored with sage but for 2007, Kasper and Swift also throw brown sugar, ancho chile powder, cider, 35 cloves of garlic and a couple of Granny Smith apples along with half as much salt into the pot. Then the turkey goes into the oven upside down over a soup of more Grannies, carrots, celery, onion, a lot of fresh basil and a quart of white wine. As promised, the process is a hot one at 450°, but in fact Kasper is steaming her turkey in all that wine for a considerable part of the unspecified cooking time. She provides no estimate of duration; the bird is done once a thigh registers 165-70°, and Kasper flips the bird after an hour to crisp the breast.

It is too much. The recipe is a mash-up and we cannot taste much of turkey, especially when bathed in definitive gravy behind all that apple and spice, chile and garlic. Perhaps the Editor may be forgiven for suspecting that the project was intended as showy and aspirational rather than realistic. In any event, the definitive brine, definitive heat and definitive Darwinian recipe have sunk like a rock from the pages of Saveur or anyplace else.

5. Or not so bad…

All this fuss appears to have provoked a reaction among the editors of Saveur. For the next Thanksgiving (2008), the recipe they chose to publish was simplicity squared, “Leah Chase’s Roasted Turkey.” Chase is a wonderful figure, the grande dame of Creole cooks in New Orleans. Jessica B. Harris, who seems to know everyone in the world of southern food, writes in the magazine that the recipe produces “astonishingly tender and juicy breast meat,” a phrase typical of her awkward and effusive style. (Saveur no. 115, 47)

The recipe is another steamer, this time enveloping the turkey in a seal of aluminum foil. Chase sheds the shell to bronze the breast for the final half hour, when she cranks the heat from 350° to 500° for the purpose. In this iteration, the roasted thigh also should reach 165-70°. No stuffing here but happily no brine either. The result is excellent if silly to consider astonishing.

Saveur carried simplicity into 2009 with a recipe for “Herbed Roast Turkey” that is not actually related to “Turkey Translated,” the article it illustrates. It is another brineless and simple preparation that gets an assist from steam. Let the oven reach 500° while you slather the bird with a sludge of butter, brown sugar, paprika, sage and thyme, then shove chopped carrot, celery, lemon and onion into its cavity. Rack the turkey over two cups of water for half an hour, reduce the oven temperature to 350° and baste the bird with more of the melted sludge a few times during the 2 ½-3 hours it should take for the thigh of a 12 pounder to reach the favored 165° temperature. A good recipe but, as noted, deficient in its absence of stuffing.

6… or tough enough.

A couple of years of common sense must have bored the people at Saveur; the magazine reverted to culinary rococo in 2010. “Consider the Turkey” featured four recipes better suited to pork including a classic choucroute garni, a mole and a roulade with spiraled boudin, along with a fifth for “Sage-Brined Roast Turkey with Oyster Dressing” from Jonathan Waxman, the erstwhile celebrity chef.

Waxman is one of those Old Boys from Chez Panisse who cunningly convinced fashionable New Yorkers to pay a premium for plain food in the flash eighties. His first and biggest splash hit town at Jams on the Upper East Side, where his line cooks grilled everything over mesquite. We never really warmed to it or him.

To make amends for minimalism, Waxman concocted a dressing (properly named; it never sees the inside of a turkey) for Saveur that requires considerably more than the single modifier to describe. This salamagundi includes bread and bacon and butter and garlic and hazelnuts and onions and oysters, both wild and white rice, and sage and stock and wine. It is ridiculous.

Waxman does not take as much interest in the bird. After brining in what amounts to a 2006 Saveur solution, a 12-14 pound bird lodges upside down in a flat 350° oven for an hour and a half and gets flipped for about 2 more, or until a thigh reaches the rather radically low level of 160°.

7. Perhaps it is perfect.

This year’s version of “The Perfect Bird” is a sort of nuptial hybrid; we get something old and something new, and some sound advice from Molly Stevens too:

“… shop for a fresh, humanely raised bird, ideally not more than 15 pounds; the gargantuan, industrially raised fowl sold by the truckload around the holidays are bland (at best) and, because they’re so big, impossible to cook evenly.” (Saveur no. 142, 27)

Then, however, she needlessly complicates things by making stock for gravy from separately purchased turkey parts ahead of time. Stevens contends that this saves time and reduces stress on the day. It does not. Simmering wingtips, neck and giblets from your turkey seasoned with herbs and aromatics need not cause concern and will perfume the house for your guests. Brown the parts before throwing them into the simmerpot; entirely unnecessary.

On to the bird. Stevens cures hers overnight but not in brine: she simply spreads it with a sensible two Tablespoons of coarse salt. She likes kosher; we like Maldon. Pat the turkey dry before salting, give it a dose of pepper too, and put it naked in the fridge. Stevens also leans on steam, but not as much as some of her predecessors at Saveur. She sets the turkey right side up--no fripperies of flipping for her--over a cup and a half of her stock; you could use yours. She drops the oven temperature from 450° to 350° as soon as she hangers the bird.

Once again some good advice followed by bad. With false precision, Stevens estimates a cooking time of “about 13 minutes per pound” but adds the sage directive to

“pierce the meaty part of the thigh with a sharp knife, and check that the juices run mostly clear with only a trace of pink--don’t wait for them to become completely clear, a sign that the turkey is overdone.” (Saveur no. 142, 28)

Done, she says, is at the point when a thermometer stabbing the thigh reads 170 which, we think, signals the same thing as those crystalline juices.

8. Stuff it.

We have done the rounds for six years; now to diagnoses. On brine and brining, britishfoodinamerica remains constant; we did not like it in our First Thanksgiving Number and do not like it now. While a salted solution will prevent a sawdusty breast, the tradeoff for the insurance is severe; mushier than tender meat, and a sharp salty tang that goes too far.

On the internal temperature that signals time to remove the turkey from the oven, Saveur quite obviously stands inconstant, decreeing variously that 160°, 165°, 165-70°, 170° and 175° perform the semiotic trick. Bet the low number to give your turkey the Stevens Test for Pinkish Juices; you always can cut a second probe but never can undo the overdone.

On the conventional wisdom about stuffing, this year Stevens articulates, if without elegance, what has gone before: “I am a firm believer in not stuffing the turkey.” (Saveur no. 142, 28) She has a point. It is true, as she says, that a bird “roasts more quickly” unstuffed, which helps prevent the white meat from drying, but we have never found, as she also says, that it “roasts more… evenly.”

It is, however, possible to produce superb turkey that is neither brined nor bereft of stuffing, and stuffing manifests an existential consequence on Thanksgiving day. The turkey flavors its stuffing and the stuffing flavors the meat, and all is well with the world, if only for an hour or few. For most of the Editor’s diners, it is the favorite dish on the table.

You will not fit enough stuffing within your turkey to satisfy a Thanksgiving crowd and need not try. Make lots of stuffing, loosely stuff your turkey with a little of it; do not forget the crop. Once your turkey has thrown some juices after an hour or so of roasting, siphon some into the remaining majority of stuffing. Bake it for no more than an hour, keep it warm and then combine it with the stuff spooned from your bird while it rests for a good half an hour.

9. Department of Education.

What have we learned from our look at six years of advice from Saveur about our Thanksgiving turkeys? ‘Nothing’ is the tempting response, but that is, just, unfair. We do know that no consensus can emerge about a foolproof method for roasting turkey (but boiling, that is another story). In reality it is not that easy, a reason other than temporary national neurosis why so many cooks find Thanksgiving a stress test and look for shortcuts and guarantees. There are none.

Other than the recipe from Leah Chase, which basically uses delicatessen technique for making succulent sandwich meats (they cook top round of beef or pastrami the same way for slicing), we do not much like the way that Saveur recommends cooking turkey.

Fortunately, however, help is to hand. The britishfoodinamerica recipe for roasting a stuffed turkey and for gravy appear this month on our front page as well as in their customary homes in our recipes and our archive. We do not pretend that the recipe is easy, but we represent that it works.

Our recipe for boiled turkey, which is easy, and approaches absolute foolproof (like absolute zero, the goal cannot be met; some cooks can wreck anything) appears in the same locations.

Happy Thanksgiving.