Our annual roundup of noteworthy books.

It was a good year for cookbooks and other publications addressing British foodways. In a breakthrough of sorts, three of the ten cookbooks recommended as holiday gifts by The New York Times Book Review come from British authors and include recipes that use British technique to create dishes with innovative as well as traditional characteristics. Our own selections follow. Rather than rate the titles, we have discussed them in alphabetical order by author. Each of these books merits purchase.

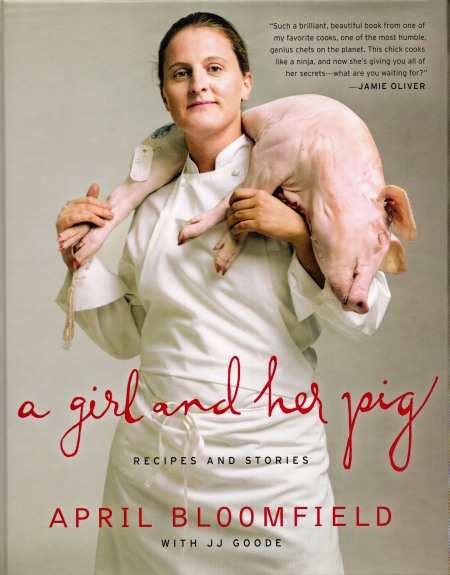

April Bloomfield with J. J. Goode, A Girl and Her Pig: Recipes and Stories.

It is nice to note that the current ‘it’ chef in the perfervid culinary world of New York is a quiet and modest working class girl from Birmingham, England. If Bloomfield’s book is more aspirational than practical, and if she ventures beyond the traditional British idiom in many of her complicated recipes, that is fine with us. As our review of the book in bfia Number 28 noted, innovation breeds the new classics and British foodways have a lively history of promiscuity.

It is nice to note that the current ‘it’ chef in the perfervid culinary world of New York is a quiet and modest working class girl from Birmingham, England. If Bloomfield’s book is more aspirational than practical, and if she ventures beyond the traditional British idiom in many of her complicated recipes, that is fine with us. As our review of the book in bfia Number 28 noted, innovation breeds the new classics and British foodways have a lively history of promiscuity.

This lovely book humbly requests the best of its readers, who will enjoy the stories and pictures. The braver sort may even give some recipes a turn.

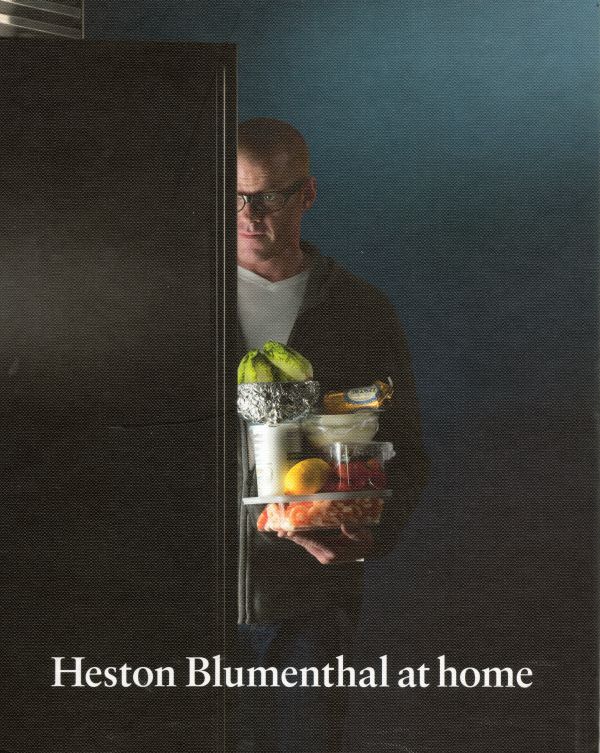

Heston Blumenthal, Heston Blumenthal at home.

With all the pyrotechnics that alight the dishes at the Fat Duck and Dinner, we might expect impenetrable prose and impossible recipes from their proprietor. We would be wrong. Blumenthal’s cookbooks always have been good; accessible despite long lists of ingredients and unorthodox methodology. Blumenthal writes with a clarity of style and purpose that should make all of us jealous.

At home is his best book yet; also his most recognizably British in derivation. Its recipes explain why he champions those unorthodoxies and guide the home cook to a culinary promised land without misstep. The Editor has a fondness for Blumenthal’s Marmite consommé and the recipe for chicken braied in Sherry with cream alone justifies the cost of At home. Blumenthal has some surprises in store beyond his use of agar agar and deionized water.

At home is his best book yet; also his most recognizably British in derivation. Its recipes explain why he champions those unorthodoxies and guide the home cook to a culinary promised land without misstep. The Editor has a fondness for Blumenthal’s Marmite consommé and the recipe for chicken braied in Sherry with cream alone justifies the cost of At home. Blumenthal has some surprises in store beyond his use of agar agar and deionized water.

For one, this acolyte of the avant-garde likes prawn, or shrimp, cocktail; as he says,“confession time, my secret vice.” It is the Old School kind sauced with nothing but cayenne, ketchup, lemon juice, mayonnaise and Worcestershire. “Being such a prawn cocktail addict,” Blumenthal is “deeply resistant to attempts to muck about with the ingredients,” although he would countenance some basil and tarragon. Blumenthal even beds his cocktail on the derided but, for this dish, indispensible iceberg lettuce.

A beautiful edition from Bloomsbury; perhaps the cookbook of the year.

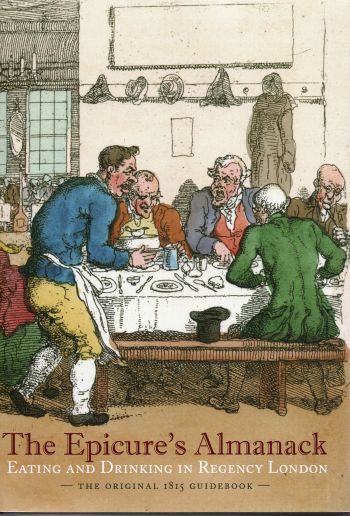

Janet Ing Freeman (ed.), The Epicure’s Almanack: Eating and Drinking in Regency London.

In 1815 Longman’s published the Almanack, written by Ralph Rylance. It was the first comprehensive guide to establishments where a reader could “dine well, and to the best advantage.” Over 650 entries describe everything from cheap oyster bars and tripe shops to elegant chop houses and the first Indian restaurant in London.

It bombed. Sales were so slow that the publisher wound up pulping most of the copies. Freeman has done considerably more than rescue a fascinating artifact from oblivion. An intimidating amount of research gets a deft reflection in the running footnotes (You need not constantly flip to the back of the book!) amplifying Rylance’s original entries. She provides histories for buildings or their sites (many of the structures Rylands visited no longer exist), divulges the contemporary reputation of various establishments and describes the nature of their clientele.

It bombed. Sales were so slow that the publisher wound up pulping most of the copies. Freeman has done considerably more than rescue a fascinating artifact from oblivion. An intimidating amount of research gets a deft reflection in the running footnotes (You need not constantly flip to the back of the book!) amplifying Rylance’s original entries. She provides histories for buildings or their sites (many of the structures Rylands visited no longer exist), divulges the contemporary reputation of various establishments and describes the nature of their clientele.

A comprehensive introduction sets the context by describing antecedent guidebooks to London (they did not much discuss food), the dining mores of the Regency city, its food markets and poor Rylance himself, a failed playwright and novelist who suffered bouts of insanity, probably battled bipolar disorder and died young.

Freeman’s achievement goes beyond the historical asset that it represents. The Almanack provides any number of fascinating details: It is fun. At the Telegraph Eating-House across from the Cross Keys Inn, for example, a basin of mock turtle soup made with calf’s head cost more than roast beef and nearly twice as much as a pork chop. Things, as they say, have changed.

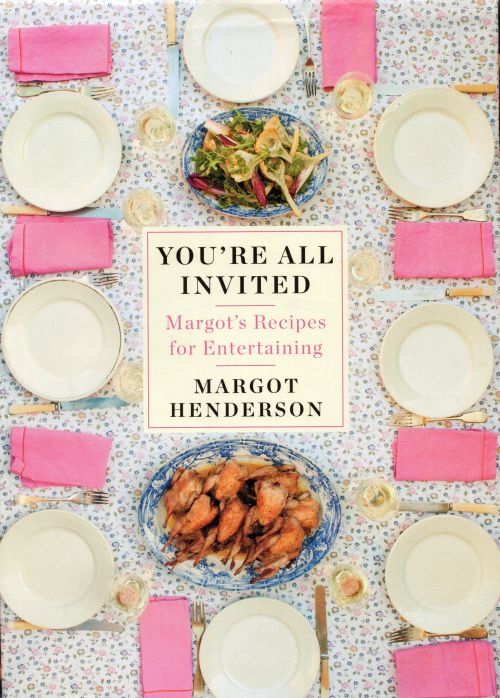

Margot Henderson, You’re All Invited: Margot’s recipes for Entertaining.

As its title indicates, the putative premise of this book is producing successful dinner parties and other culinary gatherings at scale. It is not quite so. Some of the recipes do indeed envision as many as twenty or thirty diners but others feed as few as four. No matter. The recipes, mostly of a simple sort, are a joy to cook and eat, and if the emphasis is less emphatically British than the other titles on this list, who cares? Things like sausages in parsley liquor hoist a triumphant union flag and Mrs. Henderson has written a book that would provide an excellent introduction to the modern British idiom.

As its title indicates, the putative premise of this book is producing successful dinner parties and other culinary gatherings at scale. It is not quite so. Some of the recipes do indeed envision as many as twenty or thirty diners but others feed as few as four. No matter. The recipes, mostly of a simple sort, are a joy to cook and eat, and if the emphasis is less emphatically British than the other titles on this list, who cares? Things like sausages in parsley liquor hoist a triumphant union flag and Mrs. Henderson has written a book that would provide an excellent introduction to the modern British idiom.

Tristan Hogg and John Simon, pieminister: a pie for all seasons.

The title is misleading in a grammatical sense, for pieminister contains many pies. Its cartoon graphics are hyperkinetic; the slogans that accompany each recipe jokey and sometimes labored. Not our style but not so laddish or enthusiastic! as Jamie Oliver either. Bad portents? Maybe, but the proof is in the pie and we have lusted after the ones from pieminister since first encountering them at the cozy Portcullis, high above the port of Bristol.

The title is misleading in a grammatical sense, for pieminister contains many pies. Its cartoon graphics are hyperkinetic; the slogans that accompany each recipe jokey and sometimes labored. Not our style but not so laddish or enthusiastic! as Jamie Oliver either. Bad portents? Maybe, but the proof is in the pie and we have lusted after the ones from pieminister since first encountering them at the cozy Portcullis, high above the port of Bristol.

Now we need not travel to England to slake our desire; we can make the pies, or reasonable facsimiles of them, with this exemplary cookbook: The authors admit to keeping some secrets close but divulge more than enough of their magic.

With pieminister you can, as the endpaper notes, make “lip smacking mouth watering belly filling gravy slurping pastry crunching flavour bursting big pies small pies breakfast pies family pies fruit pies pies that make you go oooooh!”

And that is not hype.

Eric Landlard, Tart It Up!

Eric Landlard, an English celebrity chef, wears the obligatory if now dated Miami Vice stubblebeard that is endemic to a certain caste. According to his garish website, “Eric has four TV series (totaling fifty episodes) to his name;” theirs are things like ‘Baking Mad’ and ‘Glamour Puds.’ These, we are told, have taken “the audience on a journey of his awe-inspiring work as well as his favourite locations that inspire his craft.” Now that is stylin’.

The site adds that his 2010 publication, Home Bake, “is undoubtedly the only baking book you’ll ever need;” so much for Jane Grigson and Julia Child. A fatuous promotional video shouts that Landlard has a “clientele that boasts the likes of Madonna, Elton John and the Beckhams.” So far, so horrible (except for Mr. John).

And so to his latest, predictably emphatic title, Tart It Up! (Get it?) It is bit of a shock that notwithstanding all this irritation the recipes--the book has lots of them--are for the most part good. The ‘spring garden tart’ laden with asparagus and peas looks like food porn at its most enticing (true to its pedigree Tart It Up! sports a multitude of lavish illustrations) and pies filled with black pudding and apple cannot go wrong. The book will help allay a phobia for many novice cooks because it includes good instructions for forming various kinds of pastry. In the end a useful gateway to what Elisabeth Ayrton has called the British “tradition of the savoury pie;” sweet ones too.

Jamie Oliver, Jamie Oliver’s Great Britain.

Oliver ‘describes’ one of his recipes, the bizarrely named, “baby yorkshire [sic] puds (creamy smoked trout and horseradish pate):”

Oliver ‘describes’ one of his recipes, the bizarrely named, “baby yorkshire [sic] puds (creamy smoked trout and horseradish pate):”

“I can’t lie…. Each mouthful is an outrageously delicious bit of heaven that anyone sensible won’t be able to resist…. This is dead quick, so easy and absolutely perfect for a starter--just whack it right in the middle of the table…. Your guests will be fighting for it, I promise… To. Die. For.”

This kind of thing breaks every rule of elegant discourse. Overwritten? I promise. Overcolloquial? O aye mate, know wot I mean? Lumbered with teenage mannerism? I can’t lie.

It would seem to get worse. Jamaican jerked pork somehow emerges, according to Oliver, from the city of Bristol, which he doubtless pronounces in estuary mode as ‘Bwistoe.’ The rabbit Bolognese [sic] sounds suspiciously Italian and a pate quite obviously is not British.

And yet… all is forgiven. No, that is not quite right. It is all, in the argot of Acadiana, good; tout va bien. Great Britain does include British recipes, updated and tweaked by Oliver in useful ways. The purple prose is genuine, for that is how he talks. Oliver is fun, Oliver is smart. He exudes a generosity of spirit and can cook. More important for our immediate purpose, he (or his ghost?) can draft a recipe that is easy to follow and may indeed produce a dish To. Die. For. And besides, that paté is no such thing but rather an authentic English potted fish paste in disguise.

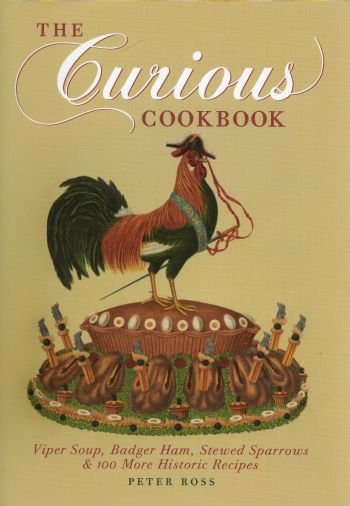

Peter Ross, The Curious Cookbook: Viper Soup, Badger Ham, Stewed Sparrows & 100 More Historic Recipes.

At first it is hard to place this book. Is Ross, Principal Librarian at the Guildhall Library in London, making fun of our forebears? He should be too serious an author for that. Does Ross advocate a return to some of these dishes with strange ingredients and stranger names? Maybe not; recipes are transcribed, and translated from archaic English, but not adapted to current practice. Perhaps the exercise is but a trifle or lark (Ross includes recipes for both). It is not a scholarly text: This compilation comes with neither index nor bibliography. The slim volume (162 recipes) leans heavily on a handful or so of sources but ranges across more than five hundred years.

At first it is hard to place this book. Is Ross, Principal Librarian at the Guildhall Library in London, making fun of our forebears? He should be too serious an author for that. Does Ross advocate a return to some of these dishes with strange ingredients and stranger names? Maybe not; recipes are transcribed, and translated from archaic English, but not adapted to current practice. Perhaps the exercise is but a trifle or lark (Ross includes recipes for both). It is not a scholarly text: This compilation comes with neither index nor bibliography. The slim volume (162 recipes) leans heavily on a handful or so of sources but ranges across more than five hundred years.

Ross himself offers little guidance. His introduction summarizes the development of cookbooks from Medieval court manuscripts to publications with recipes designed to cope with the rationing and shortages of the Second World War--all in only twelve pages. He does nod toward the notion that the past is a foreign country, and justifiably reminds readers that cultural relativism is real; “one culture might consume dog with gusto and without sentimentality and yet feel physically sick at the thought of eating that rotting, mouldering lump of fermented cow’s milk known as blue cheese.” Why, however, not identify Korea?

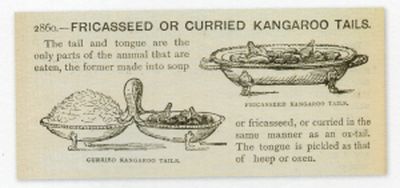

In the end this is a book for beginners and browsers, something more than fit for the bathroom. On those terms it is a bit of a gem. The Editor did not know, for instance, that the first recipe book printed in England, This is the Boke of Cokery, appeared only in 1500; The Forme of Cury, which dates to 1390 and often gets cited as earliest, was in fact a manuscript. Nor did she know that later additions of Mrs. Beeton included recipes for kangaroo soup and curry, roast wallaby and parakeet pie.

Ross does let us down, or perhaps tries too hard. He cites Horse Artillery Pudding, Gun Troop Sauce and Beef Trifle as examples of recipes “given fanciful names to make them sound more attractive,” but it is hard to see how reference to the military would glamorize food. Most such names do in fact have their genesis at the point of reference. Over the years, however, the particular troop got lost as the recipe migrated from author to author, often without attribution.

Ross does let us down, or perhaps tries too hard. He cites Horse Artillery Pudding, Gun Troop Sauce and Beef Trifle as examples of recipes “given fanciful names to make them sound more attractive,” but it is hard to see how reference to the military would glamorize food. Most such names do in fact have their genesis at the point of reference. Over the years, however, the particular troop got lost as the recipe migrated from author to author, often without attribution.

The trifle is a reference to what the word originally meant, something of little value, not to something fanciful or even curious, and not to a bizarre savory dessert. The 1917 recipe uses leftovers and cheap additions of egg, horseradish, margarine and onion; handy enough in wartime. It sounds quite good, like an Ongar ham cake but made with whatever cold meat is to hand.

Then there is the mystery of lasagna, or, at least in fourteenth century England, ‘losyns’ or ‘lozenges.’ Ross interprets the recipe, from The Forme of Cury, as instructing the cook to dry until hard thin sheets made with flour and water, boil them in broth, then layer them with cheese, spices and sugar. He notes that this “remarkably modern sounding dish [ ] is clearly the ancestor of our modern lasagna.” Or is it? Does ‘lasagna’ mean ‘lozenge? Did the English invent it? Or is ‘losyns’ an outlier? The Curious Cookbook provides no clues.

Buy the book without great expectations. It will get you thinking but not necessarily give you answers. A spry introduction by Heston Blumenthal, who confesses “with some embarrassment, that up until a decade ago I had given little thought to British culinary history,” provides added appeal.

Nigel Slater, The Kitchen Diaries II.

Slater represents one of the more refreshing figures in the culinary landscape. At the outset of this second set of Diaries he stakes his turf:

“I am not a chef and never have been. I am a home cook who writes about food. Not even a passionate cook (whatever that is), just a quietly enthusiastic and slightly greedy one…. Sharing recipes. It is what I do. A small thing, but something I have done for a while now.”

Anyone who writes that well about anything demands our attention in his quietly authoritative way.

The Diaries are in a sense misnamed; the two books do not arise from any unitary notebook but rather from “a scruffy hotchpotch, a salamagundi, of anything and everything I need to remember.” They vary “from neat essays” written with a fountain pen to “almost illegible scribbles on any bit of paper that was handy.” He is, in other words, cursed with a writer’s restless compulsion.

A natural writer devoid of pretence, his musings are at once wistful and whimsical. An iPad has usurped those scribbles, “[a] decision I now rather regret.”

Slater is self-aware but not self-involved, confessional but never maudlin:

“We have never been what you might call a ‘close’ family. A mother and father dead by the time I reached my late teens a brother who emigrated; an uncle distanced by his obsession with religion. The family member I was closest to was a mischievous, twinkly-eyed aunt whose diet consisted solely of Cup-a-Soup, Bailey’s Irish Cream and a regular swig of Benylin. She lived to be a hundred, which puts the healthy-eating lobby in its place.”

In fact his childhood was loveless and horrible, redeemed in later years by runaway success and a happy home life. These themes will be familiar to devotees of Slater, and serve the larger purpose of explaining the grip of food on his psyche. The mischievous aunt would bring him along to her mother. She was “[n]o jolly granny;” condensation marred the windows of her dark, dank kitchen, which smelled of boiling ham and coal smoke. As a wry Slater notes, “the scene was less than welcoming.”

And it may have set the foundation for his redemption. Devotees will remember that Slater loves boiled ham. Its smell still reminds him of that “tired old lady.” Now, however, it “comes with a welcome,” the promise of companionship and of caring for others, something Slater contentedly cooks “to feed the hordes.”

By now the reader knows. The stories set the stage for the recipe, “an unabashedly old-fashioned dish of boiled ham” and, Slater might have added, an unabashedly British one, with “a new sauce”--but not too new. Slater has added Jerusalem artichokes (they were lying around), mustard and lemon to the traditional napping of white parsley. An old dish, a new twist and even, perhaps, an evocation of love. You want to give this man a hug.

Cita Stelzer, Dinner With Churchill: Policy-Making at the Dinner Table.

Nobody will mistake her for Janet Freeman, but Stelzer has written an enjoyable book despite its considerable flaws. The premise of the subtitle is artificial and strained, facts are misstated (clam chowder by no means is a complicated dish), any semblance of analysis is shallow and speculation pollutes the narrative.

Nobody will mistake her for Janet Freeman, but Stelzer has written an enjoyable book despite its considerable flaws. The premise of the subtitle is artificial and strained, facts are misstated (clam chowder by no means is a complicated dish), any semblance of analysis is shallow and speculation pollutes the narrative.

After describing the food served by FDR to his White House guests during a visit by the Prime Minister, for example, Stelzer declares without evidence that “Churchill surely would have been sufficiently sensitive to the suffering of his countrymen to have compared the lush dinner with the thin fare available in Britain under the rationing programme in which he was so heavily involved.”

According to Jane Fearnley-Whittingstall in The Ministry of Food, however, this was the same ‘heavily involved’ grandee who, “[w]hen shown a week’s ration” in response to complaints about the small amount of meat, “said it would be quite enough for him. He thought it was a ration for a single meal.”

Anachronism crashes the party too. Stelzer registers surprise that before and during the Second World War, Churchill drank blended whisky. She apparently is unaware that bottling single malts for retail sales is a postwar innovation.

But if Dinner With Churchill is marred by mistakes, and if it is more hagiography than history, it also discloses delightful details and represents a refreshing corrective to all the revisionist studies portraying Churchill as a racist if not genocidal warmonger. Churchill liked British food; dressed crab, roast beef, apple pie, Stilton and particularly Irish Stew were favorites. He did pay close attention to the dinners mounted by the British delegation at the great wartime summits; he really did relish Champagne; and the White House menus presented during Churchill’s several extended visits indicate that the foodways of upperclass Americans had not yet diverged much from those of their counterparts in Britain, although Stelzer does not seem to notice.

Do not read this book as history: Read it for fun.

Tim Wilson & Fran Warde, Ginger Pig Meat Book.

Wilson runs Grange Farm and some retail shops called, suitably enough, Ginger Pig. He raises heritage breeds of chickens, cows, pigs and sheep. Although Wilson ‘teamed up’ with Warde to write the book, she or they have done well to convey his own voice. Ginger Pig is what it claims, “a meat manual for the inquisitive domestic cook.”

Wilson runs Grange Farm and some retail shops called, suitably enough, Ginger Pig. He raises heritage breeds of chickens, cows, pigs and sheep. Although Wilson ‘teamed up’ with Warde to write the book, she or they have done well to convey his own voice. Ginger Pig is what it claims, “a meat manual for the inquisitive domestic cook.”

The book includes recipes of course, but also contains other useful information presented in a clear, down to earth style. Ginger Pig explains how to joint, bone or spatchcock a bird and describes the characteristics that distinguish meat, for example, from different breeds of pig along with lots more. Photographs are descriptive and useful rather than pornographic and distracting.

The recipes themselves--many but by no means all British--are superb. Wilson has one of the best ones we have found for roast goose, with stuffing and roasted fruit, and excellent versions of homely classics like Lancashire hot pot, sausage rolls and toad in the hole.

We never much like a seasonal presentation of recipes; if you want to explore, say, a range of pork recipes you must consult the index rather than flip consecutive pages, but seasonality is justifiably au courant and other people enjoy the format. The people at Lyons Press in Guildford, Connecticut deserve thanks: Ginger Pig has beautiful production values including a place ribbon built into the spine.