Three Men, a Diary & a Dog or riverine & pooterish fare from our Rural Correspondent, being the return of our occasional series on food in books.

1889. What a year for comic fiction: A Connecticut Yankee in the Court of King Arthur, Three Men in a Boat and The Diary of a Nobody. No space here, at least not yet, for Twain, who liked his food, liked the fare at home better than what he found in Europe and wrote it all down. For now I’ll concentrate on the English authors Jerome K. Jerome and the Grossmith Brothers, mainly in the food context of course.

First, something about them; Jerome K. Jerome (1859-1927) was born in Walsall but spent most of his life in London. He left school at the age of 14 and initially worked as a railway clerk. He then tried his hand at acting, journalism, teaching and secretarial work before settling on a literary career. He wrote plays, essays and sketches, some of which were humorous and some not. He enjoyed much success but also suffered a good many flops, partly owing to his desire for recognition as a serious author by a reading public that pigeonholed him as comic. Three Men and a Boat. To Say Nothing of the Dog (to give the full title), was Jerome’s runaway success and the book by which he will always be remembered. It has been translated into many languages and repeatedly adapted for stage, radio, cinema and television.

George (1847-1912) and Weedon (1854-1919) Grossmith were both born and educated in London. Both had successful stage careers, George in light opera and Weedon as a comedy and character actor. But for all their achievements in the theatre, as writers and, in Weedon’s case, an artist, the Grossmith brothers will be remembered forever for one work. The Diary of a Nobody first appeared in instalments in Punch during 1888-89 before being published, with additions, in book form in 1892. The Diary, written mainly by George and illustrated by Weedon, was instantly “recognized as one of the most amusing novels in the English language”. (DNB) It too has been much translated and adapted. It also has spawned many pastiches, not least Keith Waterhouse’s Mrs Pooter’s Diary (1983).

Three Men in a Boat describes a boat trip between Kingston-upon-Thames and Oxford, and part of the way back, undertaken by three friends: J, George and Harris, accompanied by Montmorency the dog. Apart from recording the humorous incidents that befall his hapless voyageurs, usually in deadpan and sardonic tones, Jerome supplies historical, cultural and geographical digressions (not always comic or intended to be so) about the localities through which his characters pass, and asides about previous river trips. Though some of the comedy is forced and the book not without occasional longeurs, the Glasgow Herald of September 1889 was right to warn prospective readers against reading Three Men in Boat in any location where they could not openly laugh long and loud.

Near Oxford, by the river.

Diary of a Nobody purports to be the diary of Charles Pooter, who has just moved into ‘The Laurels’, Brickfield Terrace in the London suburb (as it then was) of Holloway. It covers a period of some fifteen months in the life of Pooter, his wife Carrie, their go-getting adult son Lupin and various friends. Pooter is a staid city clerk who knows his place but never quite appreciates what is going on around him. He is a figure of fun because of his pomposity, determination to stand on his dignity, and refusal to recognise his own foolishness. George Orwell regarded him as a modern, Anglicised and sentimentalised version of Don Quixote who ‘constantly suffers disasters brought upon him by his own folly, and surrounded by a whole tribe of Sancho Panzas’. (Orwell 787) Still, Pooter’s faults are mild, his disasters slight and motives good. Not unlike Punch itself, the Grossmith’s satire is gentle. As Orwell says, the authors ‘take pity on poor Pooter’ and, not necessarily convincingly, almost everything turns out well for him.

And so to food, which occupies a modest portion of the Diary. Although Pooter loves to potter about his house and garden, knocking in the odd tack, dabbing on a little paint, straightening the occasional picture and sowing some mustard and cress, he sets foot in the kitchen only once. He sits there one evening with his friend Gowing to avoid the séance that is proceeding in the parlour. The kitchen is the domain of Carrie, Sarah the downtrodden servant and Mrs. Birrell, the truculent and bibulous charwoman. Pooter is more ‘front of house’ but his attempts to deal with the local food purveyors who knock on his door in search of custom do not turn out well. His dignity is compromised by doorstep confrontations with an irate butcher, a drunken ‘butterman’ and several tradesmen’s boys, none of whom treat him with the respect he thinks a city clerk deserves.

Pooter likes to eat early and simply. When Lupin moves into a Bayswater flat and invites his parents and other guests for dinner at 8.00pm, his father objects to the lateness of the dining hour. Famished, he has some bread and butter at 6.00pm (when he “could have eaten a hearty meal”), and spoils his appetite. When dinner eventually arrives, after champagne and twenty minutes late, it proves “a little too grand”. To his embarrassment, all the guests other than Charles and Carrie have donned evening dress.

Though Pooter occasionally dines out on lobster (at a Mansion House function for Representatives of Trade and Commerce) and oysters (with the American journalist Hardfur Huttle), at home he and Carrie prefer plain fare such as cold mutton, chops, stewed apples and custard. For breakfast he enjoys a hard-boiled egg, an item that Sarah is incapable of cooking properly. He also likes streaky, though not ‘cushion of’ bacon, and complains about the difficulty of obtaining breakfast sausages that are not either ‘full of bread or spice, or…as red as beef’.

When Carrie prepares ‘a little extemporised supper for friends’ she serves the leftovers of a cold joint, a small piece of salmon (which her husband agrees to forego lest there is insufficient to go round), blancmange, custard and jam puffs. To celebrate Lupin’s engagement she makes little cakes, jam puffs (again) and jelly. Sandwiches, cold chicken, ham and some sweets also are provided. On the sideboard, ‘for the more hungry ones to peg into if they liked’, are a ‘nice piece of cold beef and a Paysandu tongue’.[1] The blancmange must have had few takers for its remains, to Pooter’s annoyance and disgust, are re-served on several occasions after the party. In the end he is obliged to tell Carrie (shades of Oscar Wilde) that either it goes or he does.

*******************

There are no maids, charwomen, wives or local tradesmen to support J and his friends for their fortnight afloat between London and Oxford. They are on their own except when putting up at public houses and hotels in inclement weather. Food features prominently in the book from the moment they start discussing their need for a break from the imagined rigours of their ‘demanding’ lives. Having concluded that they are all victims of serious diseases brought on by overwork, J’s landlady knocks to enquire about supper: “We smiled sadly at one another, and said we had better try to swallow a bit”. They then tuck into steak and onions followed by rhubarb tart. But J’s poor state of health means that he loses interest in food after half an hour or so and (“an unusual thing for me”) even declines the cheese course.

The travellers agree to take copious supplies on their journey; eggs, bacon, cold meat, tea, bread, butter and jam for breakfast, and pretty much the same for lunch with the exception of the egg and bacon. But when the time comes to pack, they choose pies, cakes, tomatoes, melons, grapes and so many other items that the greengrocer’s boy believes J is moving his place of residence. For his part, “the gentleman from the boot-shop” observes that: “They ain’t a-going to starve, are they”? Other neighbours wonder if they are planning a transatlantic crossing or African expedition.

Their first meal is lunch under the willows near Kempton Park. We do not discover exactly what is consumed, only that the third course consists of bread and jam. Neither do we ascertain the contents of their first supper, eaten on the river bank at Runnymede. Next morning Harris offers to prepare scrambled eggs for breakfast. By his own account he is famous for them:

“People who had once tasted his scrambled eggs, so we gathered from his conversation, never cared for any other food afterwards, but pined away and died when they could not get them.”

But Harris encounters numerous troubles in preparing the dish, from failing to get the eggs in the frying pan to burning himself. The result is “a teaspoonful of burnt and unappetizing looking mess” for which Harris blames the stove and pan. They are ready for their cold beef lunch when they reach the vicinity of Monkey Island, near Windsor but discover they have no mustard to accompany it:

“I don’t think I ever in my life, before or since, felt I wanted mustard as badly as I felt I wanted it then. I don’t care for mustard as a rule, and it is very seldom that I take it at all, but I would have given worlds for it then… I grow reckless like that when I want a thing and can’t get it.”

At least they have the consolation of an apple tart and when George extracts a tin of pineapple from the hamper “felt that life was worth living after all”.

George’s discovery of the pineapple cues the funniest episode in the book. They have canned pineapple but no can opener. They try various implements in its stead including a penknife, scissors, a sharp stone, the spiky end of a “hitcher” (boat hook) and their mast:

We beat it [the can] out flat; we beat it back square; we battered it into every form known to geometry--but we could not make a hole in it.

In the end Harris flings it into the river where it sinks to the noise of loud cursing.

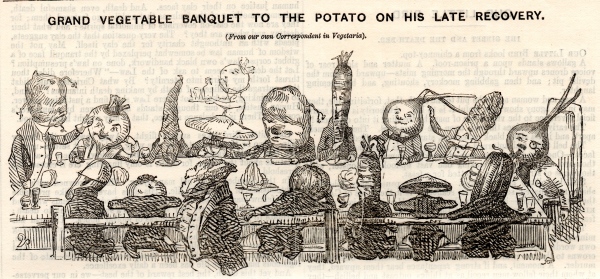

At Marlow it is time to reprovision, and our heroes do not hold back. George thinks they are not eating enough vegetables so they buy 10 pounds of potatoes, a bushel (8 gallons) of peas and a few cabbages. Other purchases include a beefsteak pie, two gooseberry tarts, a leg of mutton, fruit, cakes, bread, butter, jam, bacon and eggs.

At Shiplake George, keen to demonstrate “what could be done up the river in the way of cooking”, proposes an Irish stew. While he gathers wood for a fire Harris and J peel the potatoes. Their incompetence is such that they end up with a mass of peel and cleaned potatoes the size of peanuts. They are no better at scraping so most of the potatoes go into the pot with their skins. A cabbage and half a peck (1 gallon) of peas follow. Since the pot remains quite empty they search their provisions for further ingredients. They add half a pork pie, some cold boiled bacon, half a tin of salmon, two eggs, and other ingredients though, after some discussion, not the dead water rat Montmorency proffers. Harris was all for tossing it in but George “said he had never heard of water-rats in Irish stew, and he would rather be on the safe side, and not try experiments”.

The stew is a great success. At least, J thought so; he had never enjoyed a meal more. The peas and potatoes could have been softer and the gravy a little less rich but altogether it had “a taste like nothing else on earth”. Cherry tart and tea follow. After supper Harris became disagreeable. J thinks the stew has upset him because he is not used to high living.

The book also describes a supper of cold veal pie and cold beef

(without mustard) on the boat near Day’s Lock. At this point they are heading back to London in persistent rain. J starts yearning for whitebait and a cutlet; Harris dreams of sole and white sauce and even Montmorency rejects the remains of Harris’s pie. Before long they decide their odyssey is done. The boat is abandoned at Pangbourne and it is back to London by train followed by supper and a bottle of Beaune in a French restaurant. It is a welcome change from the cold meat, cake, bread and jam that had formed their staple diet for the previous ten days.

********************

Dickens is said to have used food in his fiction as metaphor, symbolising the inequality rife in Victorian society. Jerome and the Grossmith brothers used it mainly as a vehicle for comedy, though for the Grossmiths food, and even more so drink, also serve as a signifier of social class.

Diary of a Nobody will long be read not only for its gentle humour but its insights into the domestic manners of the lower middle classes in late Victorian England--an England where the bicycle is cutting-edge technology, cabbage, eggs, meat and butter are delivered to the door, mutton is standard fare and a letter posted in the morning can not only be delivered but also elicit a reply on that same day.

Three Men in a Boat probably will not be consulted as the definitive guide to boating on the middle Thames or as a guide to al fresco dining but will live as a classic example of English irony. A first edition can now cost some £500 ($750) which is rather more than the cost of the Grossmiths’ classic.

Instructions for Irish stew that include peeled potatoes but not pork pie, canned salmon, egg or water rat appear in our recipes.

Sources:

George & Weedon Grossmith, The Diary of a Nobody (London 1885)

Jerome K. Jerome, Three Men in a Boat (London 1885)

George Orwell, Essays (New York 2002)

[1] Paysandu in Uruguay was famous for its potted beef tongue. The British Army supplied cans of it to troops in the nineteenth century and during the First World War. Explorers in Rider Haggard’s She ate it for breakfast and dinner in the absence of fresh meat.