British Charcuterie by Jennie Reekie

A Review

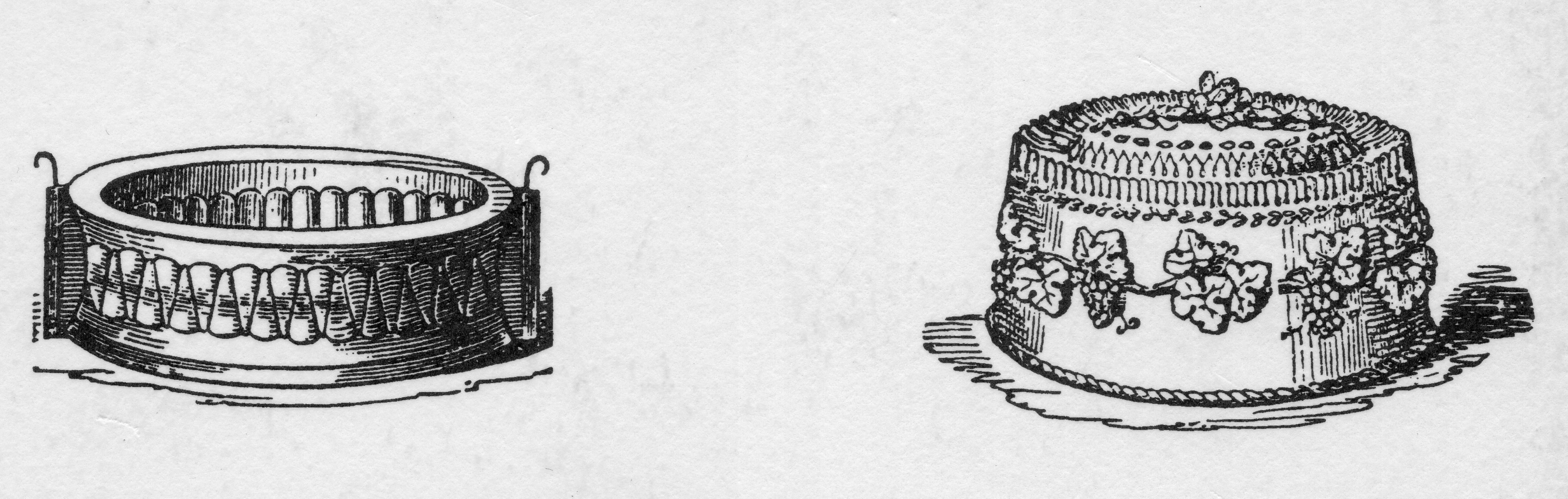

Jennie Reekie published British Charcuterie in 1988, apparently the product of someone’s promotional effort; a disc superimposed on the cover has a slogan surrounding the picture of a raised pie that reads “Discover the Farmhouse Flavours of Britain.” A cursory glance relegates this book, with its cartoonish illustrations, slightly oversized format and scant 135 pages of text, to the heap of coffee table potboilers. A closer look reveals that the first impression is unfair. This is an informative book on a neglected subject that wears its scholarship with grace and verve. Perhaps even better, depending on your point of view, are the recipes.

Jennie Reekie published British Charcuterie in 1988, apparently the product of someone’s promotional effort; a disc superimposed on the cover has a slogan surrounding the picture of a raised pie that reads “Discover the Farmhouse Flavours of Britain.” A cursory glance relegates this book, with its cartoonish illustrations, slightly oversized format and scant 135 pages of text, to the heap of coffee table potboilers. A closer look reveals that the first impression is unfair. This is an informative book on a neglected subject that wears its scholarship with grace and verve. Perhaps even better, depending on your point of view, are the recipes.

‘Charcuterie’ is not usually a term associated with Britain, but its definition after all is just “pork products, as hams, sausages, and pates.” (at www.Dictionary.com) In this respect the book’s title is a little misleading; it is a stretch to include things like Cumberland sauce, pea soup and trout under the rubric merely because the preparations complement or incorporate a little pork but the recipes are welcome anyway.

In any event, however, the term ought be associated with Britain because the Islands have an ancient tradition of rearing heirloom breeds like Gloucester Old Spot and Tamworth pigs. The great regional hams with their distinctive cures and flavors rival the best that France, Italy, Vermont and the American south have to offer. Sausages are a staple, and Britain also developed its own characteristic galantines (which originated there), terrines and potted meats. In this context it therefore is surprising that so little print has been devoted to the subject, and if British Charcuterie is hardly definitive, it makes a sound start.

Reekie introduces her subject with a short historical essay that is a little folksy, but not too bad, followed by a quick survey of hog husbandry before leading off the recipes with a chapter on “Fresh Meat Products.” The next seven chapters each consider the preparations of a particular region before the text concludes sensibly enough with a penultimate one entitled simply “British Heritage” because “[i]n a book such as this it was inevitable that there would be some recipes which were commonly made throughout the British Isles but did not have any regional bias” (Reekie 124) and a final section on (then) contemporary and original restaurant preparations.

Reekie introduces her subject with a short historical essay that is a little folksy, but not too bad, followed by a quick survey of hog husbandry before leading off the recipes with a chapter on “Fresh Meat Products.” The next seven chapters each consider the preparations of a particular region before the text concludes sensibly enough with a penultimate one entitled simply “British Heritage” because “[i]n a book such as this it was inevitable that there would be some recipes which were commonly made throughout the British Isles but did not have any regional bias” (Reekie 124) and a final section on (then) contemporary and original restaurant preparations.

This last chapter is entitled “Looking Ahead;” it is entirely appropriate for, as Reekie reminds us, [f]ood and cookery does not stand still but is perpetually changing and developing.” (Reekie 136) Some recent writers go so far as insisting, in direct opposition to the great Elisabeth Ayrton, that we cannot possibly recreate the food eaten by our ancestors due to the evolution of husbandry, methodology and technology over the centuries no matter how carefully we consult the old manuscripts or laboriously we utilize archaic equipment. That debate, however, would be the worthy subject of another essay.

The regional basis of organization that is so irritating and inaccessible to nonspecialist recipe hunters in general cookbooks actually is appealing in British Charcuterie because the only subject is pork and the regional variations on the food are noteworthy. It is, however, somewhat arbitrary; recipes for items like Cambridge, Cumberland, Oxford and other sausage varieties appear in the chapter on ‘fresh’ products along with Melton Mowbray and Yorkshire pies, Lincolnshire brawn and other recipes that ought logically to appear in the regional sections.

The book is imperfect; the discussion of those regional hams is cursory and there are lacunae: Reekie writes, for example, that

“Twenty years ago I remember hearing about how wonderful the sausages from Epping were, doubtless due to the large herds of pigs the forest used to support. Unfortunately, little is heard of them these days.” (Reekie 29)

Putting aside the obvious lack of causal connection between herd size and sausage quality (industrial pork farms produce lots of crap in both senses of the word), we get no description of an Epping sausage: What was it made from and why was it distinctive? Did the style vanish when the pigs left Epping? Not necessarily; The Editor makes Melton Mowbray pies in Rhode Island. A little research on this and other subjects would have improved British Charcuterie.

For instance, Reekie skirts a subject of great mystery. Alone among European based cuisines, Britain has no tradition of hard, smoked or cured sausages that do not require refrigeration; we have yet to find an explanation for the anomaly. Reekie tantalizingly writes about “some of the delicious smoked sausages” she found in Suffolk but does not otherwise describe them (she does compare them to “Polish cabanos,” whatever those are). Are these Suffolk smoked sausages a unique traditional specialty, inauthentic impostors or a recent innovation? Are they the product only of an individual smokehouse or butcher? It would be good to know more.

We decided to find out. Reekie got her smoked sausages from Emmett’s of Peasenhall, logically enough in Suffolk, during the 1980s. Happily they still are going strong and, occasionally, still smoke sausages. They smoke a number of other pork products too, and make the estimable black ham of Suffolk.

Emmett’s is a wonderful place and Mark Thomas, the proprietor, is engaging and personable. He also is generous with his time, so we were able to learn more about his smoked sausages. The word ‘his’ is a deliberate choice; he decided to maximize the exploitation of his smokehouse years ago by smoking some of his bangers. It is not a traditional method in Britain.

Mr. Thomas takes his basic sausage recipe to make the smoked variant; sometimes he adds additional seasonings to the basic mix; sometimes he uses lavender, which goes into a number of his other products too. The sausages lose about half their volume during the smoking process; they are snack food for dipping in mustard and munching with beer. They are not the missing hard sausages of Britain after all, not an English salami; they are not hard at all. They sound delicious.

Mr. Thomas does not know of any traditional hard-cured English sausage, and it remains an abiding puzzle why, apparently, the British have not developed one. Even tiny Rhode Island has an indigenous cured sausage, called soupy, an obvious derivation of the Italian sopressatta. Soupy, however, is emphatically not sopressatta. It does not incorporate pure fat; no white flecks dot the filling and it also uses smaller casings so it has a lesser circumference. Because it is such lean sausage, soupy becomes almost rock hard after curing, which adds to its originality. Soupy is salty enough not to require refrigeration, although Rhode Islanders store it under an oil bath to preserve it.

A bedrock characteristic of authentic soupy is heat; commercial producers as well as home cooks make versions laced with an almost unimaginable amount of cayenne (not the traditional southern Italian dried red chili flakes and seeds). Sliced thin to the point of transparency and eaten with nothing but good bread, plenty of red wine or good beer and perhaps some olives, soupy is terrific.

It also is a Rhode Island institution. Each winter home cooks all over the state hold soupy parties to lay down the annual batch of sausage and it is a welcome gift for those of us uninitiated in the ritual. The soupy that the Editor’s friends Robert and Robyn White make annually is particularly good, although it does vary in heat. Commercial versions in several grades culminating in ‘nuclear’ hot are available from several reputable producers; Fortuna’s for one has a thriving mail order business. (Fortuna's)

Soupy from Fortuna's

Someone in Britain ought to shoot this gap in the market and develop a spice mix and cure, smoky or dry, for a characteristically British hard sausage.

Back to British Charcuterie, the recipes themselves--which really are the point--more than offset any research omission or categorical confusion. They are clear and concise, they work, and range from quick, simple preparations and good recipes for homemade sausage (sprightly Oxford sausages include a hint of citrus and do not even require casings) to an accessible method of home curing salt pork and brining the meat with robust spice to make pickled pork.

Some of the recipes are unique variations on traditional themes, or at least had been unfamiliar to The Editor before reading this book. Two examples: Reekie makes delicious skuets (skewers of meat and vegetables, usually made with sweetbreads) out of pork and kidney seasoned with ground coriander, ginger and mace, and includes a mittoon (or stuffed rib of pork) laced with brandy and layered with forcemeat.

This is a worthy little cousin to Jane Grigson’s Charcuterie and French Pork Cookery and deserves a revived print run.