College cuisine

In which our Rural Correspondent ventures into town for lunch and the Editor adds some observations on Elizabeth David and the nature of institutional food.

Can one eat badly in Britain? Not so long ago the question would have induced puzzlement, if not expletives and expostulations from Europeans, North Americans and others, including many Britons. Recollections of appalling meals in motorway service stations might have ensued. As the pages of britishfoodinamerica and other sources show, things have changed in recent years, at least in some quarters. In truth, at any given time the opening question could elicit an affirmative answer whether posed in relation to the UK, USA, France, Italy or anywhere else. In “Eating Out in Provincial France,” for example, an essay written for Alan Davidson’s Petit Propos Culinaires during 1980, Elizabeth David famously lamented the decline in French provincial restaurant standards that marked the 1970s. Like her, your Rural Correspondent has experienced some memorably dire meals in French restaurants as well as many that have been stunningly good.

The fact is that it has always been possible to eat well in Britain. It is more a case that the domestic and especially commercial default was poor to average, whereas in France, it used to be above average or better.

The purpose of this article is to report a notably awful luncheon in 2009, at an Oxford college that will remain nameless. Your Rural Correspondent was the guest of a visiting Canadian academic sentenced to a sabbatical year of dining in the college. It should be said that our arrival was somewhat late owing to some extended pre-lunch consumption of the excellent Adnams Broadside available in the Rose & Crown on North Parade Avenue only a few steps from the college entrance on Woodstock Road. As a result, several items on the lunch menu were ‘off’ (as in, no longer available). I reluctantly ‘chose’ some steamed fish of indeterminate species accompanied by corn (in July and out of a can for sure) and cauliflower in a white(ish) sauce to which the word mornay could be applied only jocularly. A lengthy stay on the steam table had led to the formation of an unappetising skin on this sauce. As an ensemble the dish lacked colour, texture and flavour. What it had in abundance was bone, large, medium and small, much of it concealed among the mealy corn and mucky cauliflower. It almost requires a perverse talent to cook like this; it was my worst meal in years. The food put me in mind of provincial school lunches in 1960s Britain, though thankfully without the presence of a harridan enjoining diners to consume every scrap in the proverbial interest of the starving children of the world.

The purpose of this article is to report a notably awful luncheon in 2009, at an Oxford college that will remain nameless. Your Rural Correspondent was the guest of a visiting Canadian academic sentenced to a sabbatical year of dining in the college. It should be said that our arrival was somewhat late owing to some extended pre-lunch consumption of the excellent Adnams Broadside available in the Rose & Crown on North Parade Avenue only a few steps from the college entrance on Woodstock Road. As a result, several items on the lunch menu were ‘off’ (as in, no longer available). I reluctantly ‘chose’ some steamed fish of indeterminate species accompanied by corn (in July and out of a can for sure) and cauliflower in a white(ish) sauce to which the word mornay could be applied only jocularly. A lengthy stay on the steam table had led to the formation of an unappetising skin on this sauce. As an ensemble the dish lacked colour, texture and flavour. What it had in abundance was bone, large, medium and small, much of it concealed among the mealy corn and mucky cauliflower. It almost requires a perverse talent to cook like this; it was my worst meal in years. The food put me in mind of provincial school lunches in 1960s Britain, though thankfully without the presence of a harridan enjoining diners to consume every scrap in the proverbial interest of the starving children of the world.

Admittedly, this was institutional food, and David among others has written at some length on its typical inadequacy. She loathed institutional food, and in particular food served by British institutions. In 1964, she wrote that British “hoteliers and restauranteurs are … behind the times. Dismayed that they can no longer get away with serving, uncriticised, the dreariest food in Europe, they turn upon the public in the furious indignation engendered by the knowledge that they are wrong.” (“A Taste of England,” Petits Propos Culinaires 66 December 2001)

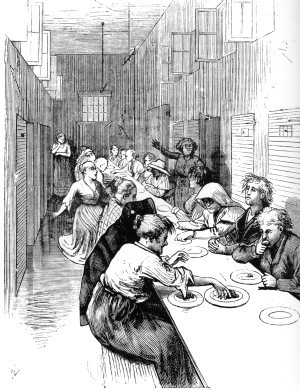

Institutional dining (at the insane asylum).

David had historical as well as personal reasons for her disdain. In 1947, holed up in a dank hotel in Ross-on-Wye (with one of her married lovers while her husband was posted to India by the British Army), David

“was finding it very difficult indeed to swallow the food provided in the hotel. It was worse than unpardonable, even in those days of desperation [rationing remained in effect in Britain until 1954]; and oddly, considering the kindly efforts made in other respects, produced with a kind of bleak triumph which amounted almost to a hatred of humanity and humanity’s needs.” (“John Wesley’s Eye,” The Spectator 1963)

This ‘unpardonable food’ included “flour and water soup seasoned solely with salt and pepper; bread and gristle rissoles; dehydrated onions and carrots; corned beef toad-in-the-hole. I need not go on.” (“Wesley’s Eye”)

The hotel in question was owned by the big, decidedly institutional Trust Houses Ltd. (later ‘Trust House Forte’) chain, and, if David is to be believed, she found damning evidence that the quality of this food was the product of institutional policy rather than negligence or scarcity. According to Artemis Cooper, David found a “very large” book “in the shadows of a bookshelf” located in her room, “and on the cover was printed CONFIDENTIAL: TO BE KEPT IN THE SAFE... It was a pre-1939 Trust House hotel cookery book, catering and food-costing manual.” (Artemis Cooper, Writing at the Kitchen Table, London 1999, 132) This volume was no less than a detailed guide to defrauding hotel diners. According to David, it included instructions for making “lobster patties for twenty-five with one lobster and I forget how many pounds of cod;” stretching “food already prepared to feed twenty hotel residents into a banquet for forty” upon an influx of unexpected diners; “a detailed instruction on how to make imitation French sauces” and more. (Cooper 132)

David later wrote that the temptation to steal the book was “truly appalling: I wish now that I had looked... for someone with a typewriter to copy out for me some of its most instructive pages. I... would have been in possession now of the secrets of Trust House.... ” (Cooper 132, citing David Papers, “early draft of ‘How it All Began’ ”) She did not steal or copy it, however, and never found another copy even though she and her then-companion “lived” from then on “in their separate lives... in the hope of tracking down another copy of this book. Both were resourceful bibliophiles.... They never found one.” (Cooper 132-33) All this may sound more than a little apocryphal and even implausible but it makes a good story and catches the flavor of much British hotel food during the postwar decades.

Times have changed over the last half century, however (or perhaps not, at least not everywhere, based on your Rural Correspondent’s experience at the college), and in any event even institutions have an obligation to provide something that is at least vaguely palatable. They have the wherewithal: Tate Britain is justifiably proud of its dining room, and scores of American colleges and universities use the quality of their food as a marketing tool to attract students.

Lest readers think that academics should have their minds on higher things than their stomachs, whether physically or philosophically, Oxford University runs an annual symposium on food: It is internationally renowned and publishes its Proceedings. Besides, many Oxford colleges now open their classrooms, residence halls and restaurants to British and overseas visitors during the summer vacation--at a price--so beware.

The college has no excuse for falling down on food, particularly when, in common with other Oxford colleges, it boasts an enviable cellar. According to one of its antagonists, the particular Oxford college that perpetrated its ‘food’ on your Rural Correspondent boasted an endowment of some £30 million as of 2006, and it gets the usual university handout from the British government. Although the college was founded only in 1950, it is, according to its website, “the most cosmopolitan of the university’s seven graduate colleges,” so it cannot be considered indifferent to subjects beyond a narrow specialist core.

The college researchers address international relations, economics, politics and history, with a decided emphasis on the eastern hemisphere and in particular the former eastern bloc, Middle East and Asian nations. Some half its fellows and students typically speak English as their second language; some of them must come from cultures that value food. Alumni who write in English include the journalists Anne Applebaum and Thomas Friedman, historians A.C. Bayly and Paul Kennedy, and statesmen Richard Haass and Gary Hart. These people are not known for slumming. What did they eat when they attended the college? How could they put up with it?

Back at the Rose & Crown, they say they cook “consistent, uncomplicated value, at honest prices.” We should have stayed for another pint (Oxfordshire’s own Hook Norton ‘Old Hooky’ also is available in cask) and ordered something to eat. The plain food leans to locally sourced, simple grills--steak (from Alden’s butcher in Oxford market), trout, ham (“with egg and/or pineapple,” which seems to be making a comeback; Rowley Leigh’s recipe in the 16-17 Weekend FT is for pineapple upside down cake) and chicken with caramelized honey--along with omelettes and sandwiches. There is a ‘pint of sausages’ available too, and hot dishes come with chips (aka fries, America). This is indeed plain, even retardataire British pub food but it is both straightforward to cook and appealing to the diner; even the kitchens of the college under discussion ought to find a way to handle it with competence and might give it a try.

Oxford colleges are, of course, singularly different institutions from the ones David excoriated, but the approach to food of at least the one at issue is indistinguishable from those that she scorned. Oxford colleges may be wonderful institutions, but who would want to eat in an institution that treats dining like a crooked hotelier or the commissary at one of H.M. prisons?

Notes.

“John Wesley’s Eye,” the Spectator essay cited in this review, is reprinted in Elizabeth David, An Omelette and a Glass of Wine (New York 1985).

The papers of Elizabeth David now are lodged in the Schlesinger Library of Harvard University; most of her collection of annotated cookbooks is lodged in the Guildhall Library, London.