An Appreciation of British Soups

“Soup,” Jane Grigson tells us, “is a primitive dish…, at least as old as the making of metal pots.” (English Food 1) The word itself derives from ‘sop,’ which meant “bread dipped or soaked in water or wine before being eaten or cooked.” (Boyd 113) Pottage, however, an earlier English term for soup that left common usage only in the eighteenth century, literally means “something made in a pot.” (White 22)

Soup by any name is ideal in the winter months when our bodies are chilled, our houses dry and our dispositions fragile. It is comfort food in any cuisine.

George Orwell is unequivocal on the subject. “British soups are seldom good, and there is hardly a single one that is peculiar to the British Isles.” (Orwell 2) He adds that therefore “we can leave both soups and hors d’oeuvres out of account. Most British people are inclined to despise both…. ” (Orwell 2)

Mrs. Grigson concurs with Orwell on the subject of quantity but demurs on quality: “The best English soups are unrivalled, but one might wish there were more of them.” (English Food 1) Nonetheless she includes some thirty soup recipes in English Food and adds another dozen and a half in The Observer Guide to British Cookery. Only a handful of these soups have roots in either the Raj or in British nations other than England itself, so that distinction cannot explain her characterization of the English soup tradition as limited. Nor does she include a number of historically significant soups like turtle or staples like lobscouse, the soupy stew that gives Liverpudlians their nickname of scouser. Elisabeth Ayrton also outlines fifty different recipes In The Cookery of England alone (there is, of course, some overlap with Mrs. Grigson, but by no means congruity).

Some just can’t get enough soup

With the exception of a few misguided concoctions like pickle soup from Elizabeth David, who anyway is no devotee of British cuisine and tends to the inauthentic when she does address the subject, our experience of British soups has been uniformly congenial.

We therefore find the statements of both Orwell and to a lesser extent Mrs. Grigson puzzling. Orwell can be dismissed out of hand. As Mrs. Grigson explains in English Food, “[s]oup, or pottage as it was called, was eaten by everyone in the earlier centuries of our history.” (English Food 1) “Soup has always been important in England” according to Mrs. Ayrton, who cites an 1852 text to demonstrate “how seriously soup, and above all turtle soup, was taken by the English gourmet.” (Ayrton 311, 312) For the middling classes, and particularly for travelers dining at inns during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, “[s]oup was the proper beginning of all English dinners.” (Ayrton 313)

Farther down the social scale and back further in time, from the eleventh and into the eighteenth century, “the daily main meal for the ordinary working man consisted of a simple pottage or broth, eaten with bread.” (Boyd 127) As Andrew Boorde, the great sixteenth century traveler, observed: “Pottage is not so much used in Christendom as it is used in England.” (English Food 2) These staple dishes relied heavily on vegetables and “the imaginative use of cultivated herbs.” (Boyd 127) Sometimes, however, especially in more prosperous households, pottages included a whole game bird for each diner, a grouse or partridge, or a bigger bird or chunk of meat for the several diners to apportion at table. (Ayrton 312)

There are in fact plenty of distinctively British soups, despite Mrs. Grigson’s comment, and no paucity of good ones, despite Orwell’s. Admittedly, whether or not British cooks in a given era could execute these recipes for soup with any competence is a different question. In 1845, for example, Eliza Acton wrote in Modern Cookery for Private Families that “[t]he art of preparing good, wholesome, palatable soups, without great expense,… has hitherto been very much neglected in England,” but rather than writing off soups as Orwell would have her do, she instead provides detailed and eloquent instructions for their preparation. (Acton 22; emphasis in original)

There are in fact plenty of distinctively British soups, despite Mrs. Grigson’s comment, and no paucity of good ones, despite Orwell’s. Admittedly, whether or not British cooks in a given era could execute these recipes for soup with any competence is a different question. In 1845, for example, Eliza Acton wrote in Modern Cookery for Private Families that “[t]he art of preparing good, wholesome, palatable soups, without great expense,… has hitherto been very much neglected in England,” but rather than writing off soups as Orwell would have her do, she instead provides detailed and eloquent instructions for their preparation. (Acton 22; emphasis in original)

Here at britishfoodinamerica we have stumbled upon scores of British soups without attempting any definitive research. In 1747, Hannah Glasse published some two dozen recipes for soup (including thornback) in the bestseller of the century, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy; in Modern Cookery Eliza Acton devotes thirty six pages and sixty three recipes to soups, most of them British. Theodora FitzGibbon weighs in with seventeen more from The Art of British Cooking and her Taste of.... series includes more, regional, variations.

The inquiry on numbers takes a decisive turn upon reference to Lizzie Boyd’s British Cookery, which includes some eighty seven distinctively British soup recipes, along with descriptions of a rose hip soup thickened with cornstarch that is spiced with cinnamon, and a mustard soup made from “thickened white stock flavoured with onion juice and mustard” that appears at least as early as 1375. (Boyd 127, 136) Oddly enough, while Boyd includes several versions of mock turtle soup, the genuine article is absent from her compilation; even more surprising, Eliza Acton does the same thing a century earlier during the height of vogue for the specialty. The explanation may lie, as Sheila Hutchins notes, in the difficulty of butchering large turtles at home. (Hutchins 38: “The soup is not one that should be attempted domestically.”)

A number of Boyd’s recipes originate in Scotland, and Scottish cooks historically have had a particular affinity for soup. They have created a lot of good ones, including cockaleekie, cullen skink, partan bree, powtowtie (a former breakfast constant made with sheep’s head) and of course Scots Broth. We will discuss them along with the rest of the Scottish cooking canon in an upcoming bfia number.

What, after all, are these various soups of Britain like? Whatever their characteristics or name, the term itself has been around for a long time. According to Eileen White, who has devoted an essay to the subject:

“Soup first appeared in England in the middle of the seventeenth century, and was featured in printed recipes from the early 1700s. This means the term ‘soup’ began to be used at this time, and the recipes came to be printed in cookery books, but the dish itself has a much older pedigree.” (White 19)

Pea soup may or may not trump mustard as the oldest. A recipe for “Perrey of pesoun,” a pureed pea soup, appears in The Forme of Cury, the oldest printed English cookbook, which dates from about 1400. (Hieatt & Butler 114) It reappears as pease pottage in Robert May’s Accomplisht Cook from 1660. (May 421)

Pepys refers to “Soup made of pease” (which he liked) in a diary entry from 1668 (White 20) but the first printed use of the term soup in a cookbook, for pease or otherwise, appears to be from The Receipt Book of Ann Blencowe. Her recipe “To make peas soope” was published in 1694. (White 20) Sometime following the turn of that century, pea soup became a ubiquitous London street food, but now has faded from all but the most modest restaurant tables. It deserves revival.

Mrs. Ayrton identifies five distinct categories of English soup (clear; two types of thick soups, one made with cream and the other with roux; broths; and fish soups). One defining aspect of them all going back to the medieval period is a generous slug of alcohol, whether brandy, Madeira, Port, Sherry, wine or less frequently beer. (English Food 2, 5) Mrs. Ayrton also maintains that “[t]he traditional soups of English cooking are real turtle, mock turtle, oxtail, game soup, pea soup, hare soup, gravy soup, asparagus and mushroom soup, but many others, such as chicken, artichoke, spinach or tomato can be as good.” (Cookery 313) We should add almond, kidney (many variations), lettuce, parsnip, spiced and onion soups, and many others.

By the end of the 1700s, turtle soup had become a national mania. The great reformer and chef Alexis Soyer believed that the dish arrived in Britain at the beginning of that century, but “only at the tables of the large West Indian proprietors, from whom it progressed to those of the City companies. During the time of the South Sea Bubble,... turtle soup was the height of fashion.” (Hutchins 37)

According to Sheila Hutchins (who included two dozen recipes for soup, though none for turtle, in her English Recipes and others),

“[d]uring the Regency and for the best part of the nineteenth century the turtle was ‘esteemed the greatest luxury which has ever been placed upon our tables.’ The great English specialty, it was for long obligatory at diplomatic and ceremonial banquets and as indispensable as whitebait.” (Hutchins 37)

By midcentury, turtle soup had become the centerpiece of the annual Lord Mayor’s Banquet in the City of London, a spot it never has relinquished. Otherwise, however, turtle soup has virtually disappeared from British tables, although it remains a fixture in the traditional restaurants of Philadelphia and New Orleans. A number of Louisiana and Pennsylvania cookbooks include recipes for what amount to modern ‘mock’ turtle soups; you can substitute beef for the amphibian meat.

Traditional mock turtle soup, essentially a stew of calf’s head, is considerably rarer; so rare, in fact, that nobody at britishfoodinamerica ever has seen it on a menu, although the proprietors of Tout Va Bien in Manhattan, where a superb tête de veau is a menu fixture, are familiar with the English dish. It was particularly popular during the sixteenth century among the victors of the English Civil War: These Puritans even established a “Calf’s Head Club” where the soup “was eaten as a symbol of scorn towards the recently beheaded King Charles I.” (Boyd 121)

We cannot say enough good things about oxtail soup which, however, also is increasingly difficult to find. The tail is the perfect cut for stock, with its high gelatin content and deeply beefy flavor. The older cookbooks offer both thin and thick versions, and remarkably enough the Knorr packet of dried oxtail is more than serviceable as a base for creating a quick stone soup loosely based on the authentic rendition. Back to the past, Eliza Acton’s slow cooked version includes carrots, celery, onion and turnip flavored with cayenne, cloves, mixed herbs and ham.

Whether or not a reader reasonably familiar with English food has sampled any of these last three soups, she likely will have known of their existence before beginning this essay. That is not the case regarding a number of other traditional English soups, including the gravy, kidney, spiced and onion soups previously noted.

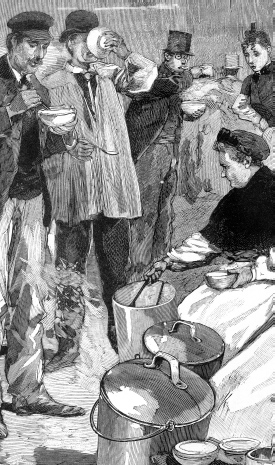

The soup is served

Gravy soup (which, despite its canonical status in Georgian and Regency cookbooks, Boyd and others also omit) may strike twenty first century readers as an oddity. It is not, however, what it may seem. The usage of ‘gravy,’ like other terms including sentiment, has changed with time.

We think of sentiment as something exclusively emotional, a word nearly indistinguishable from ‘sentimental.’ When David Hume or Adam Smith used the term, however, they meant something different, and complex:

“Sentiments were feelings of which one is conscious, and on which one reflects. They were also events that connected the individual to the larger relationships in which he or she lived (the society, or the family, or the state). The traffic or commerce of modern life was at the same time a traffic in opinions and sentiments. The ‘man of society,’ in Smith’s translation of Rousseau’s Discours sur l’inegalite[sic], is ‘always out of himself;’ he ‘cannot live but in the opinion of others, and it is from their judgment alone that he derives the sentiment of his own existence.’” (Rothschild 9)

So it is with gravy. When Hannah Glasse or Eliza Acton used the term in conjunction with soup, they did not refer to pan drippings mixed with water or stock and thickened with flour. Instead, gravy soup was something like a consommé or bouillon, usually based on beef, a clear soup distinguishable from its French counterpart by aggressive seasonings of cayenne, chili, clove, mace, white pepper, mushroom ketchup and soy or Harvey’s sauce in various combinations. (Glasse 23; Acton 28-29) This is not a little ironic given the conventional wisdom that English food is blander than its continental counterparts.

The kidney and lettuce soups are self descriptive; the other two perhaps not. Spiced soup is the byproduct of eighteenth century recipes for meat simmered with typically Georgian seasonings of mace and turmeric, and subtly delicious in its own right. The onion soup under discussion is a light white soup made with apples and cider, then finished with a little cream. It is utterly distinct from its French counterpart.

All of these soups with the exception of traditional mock turtle are straightforward, rewarding and deserving of revival. Many of them have flavors that will be unique and uniquely appealing to contemporary diners so give one or a few of them a try during these darkened wintry days.

Soup recipes appear in the practical.

Sources:

Elisabeth Ayrton, The Cookery of England (London 1974)

Eric Blair, British Cookery (unpublished ms. 1946), available at theorwellprize.co.uk

Andrew Boorde, A Compendyous Regymen or a Dyetary of Healthe (London 1562)

Lizzy Boyd (ed.), British Cookery (Woodstock, NY 1979)

Theodora FitzGibbon, The Art of British Cooking (London 1965)

Hannah Glasse, the Art of Cookery Made Plain & Easy (London 1747)

Jane Grigson, English Food (London 1974)

Constance Hieatt & Sharon Butler (ed.s), Curye on Inglysch (Oxford 1985)

Sheila Hutchins, English Recipes and others from Scotland, Wales and Ireland (London 1967)

Tom Jaine, “The English Kitchen: Introductory Remarks,” in Eileen White (ed.), The English Kitchen (Totnes, Devon 2007)

Robert May, The Accomplisht Cook (London 1685), Prospect Books facsimile (Totnes, Devon 2000)

Emma Rothschild, Economic Sentiments: Adam Smith, Condorcet and the Enlightenment (Cambridge, MA 2001)

Eileen White, “Warm, Comforting Food: Soups, Broths and Pottages,” in Eileen White (ed.), The English Kitchen (Totnes, Devon 2007)