Traditional Food in Wales from our Education Correspondent

Memories of a midcentury childhood.

1. We once all were locavores.

When I was a child growing up in Wales during the 1950s it never occurred to me that what I was eating might be different from food elsewhere in the United Kingdom. We ate what my mother and her family had eaten when she was young; my grandfather was a keen gardener and grew all of our vegetables. After he died, we had to buy them either from the local farm or the greengrocers. Some of the meat we ate came from my godmother’s farm--spring lamb, beef and pork, although most came from the local butcher and local farms. Most of my friends ate similar food as they too had parents who grew their own vegetables and bought locally produced meat. Food was never fancy: It was meant to fill you but it always had flavour.

What I did not know and only learned as I grew older was that traditional Welsh cooking derives from the diet of the workingman, the fisherman, farmer, coal miner or labourer. As with my own experience of childhood, it is often hearty and made from local ingredients and, in the home at least, always full of flavour. Fresh vegetables from the garden, fish from the rivers, lakes or sea, meat from the family pig; these form the basis of traditional Welsh cooking. Welsh lamb and beef also feature prominently as do freshly caught fish including salmon, sewin (sea trout), brown trout, crab and cockles.

What I did not know and only learned as I grew older was that traditional Welsh cooking derives from the diet of the workingman, the fisherman, farmer, coal miner or labourer. As with my own experience of childhood, it is often hearty and made from local ingredients and, in the home at least, always full of flavour. Fresh vegetables from the garden, fish from the rivers, lakes or sea, meat from the family pig; these form the basis of traditional Welsh cooking. Welsh lamb and beef also feature prominently as do freshly caught fish including salmon, sewin (sea trout), brown trout, crab and cockles.

As a family we rarely ate out; in fact I was 12 before I ate in a proper restaurant on the occasion of my sister’s twenty-first birthday, which probably was just as well, for until recently it was difficult to find good traditional Welsh cooking outside the home. I remember how disappointing my own family found the quality of the food in restaurants and public houses during a visit to North Wales in the 1970s. It was bland and even tasteless fuel for the stomach more than sustenance for the soul. More recently my husband, a keen fisherman, started going to Rhayader to fish the Elan Valley Reservoirs. Although he looked forward to the fishing, his visits hardly were enhanced by local meals stuck in the poor cuisine of the 1950s. Nowadays this is changing and traditional Welsh produce, beautifully cooked and presented, is found much more frequently throughout the country.

2. The produce of Wales.

Many speciality foods now are grown and prepared in Wales, from honey to ham, cockles to prepared sauces, white wine to whisky, and ice cream to yoghurt. My favourite food as a child was cawl (pronounced like ‘cowl’), a broth or soup. On a cold winter’s day, arriving home, frozen, from school, nothing was more welcome than a bowl of cawl. It  is a classic one-pot meal and the homely national dish, originally cooked in an iron pot over an open fire using the local ingredients: home-cured bacon, scraps of lamb, Swede [Editor’s note: turnip], potatoes plus the Welsh staple vegetables of leek and cabbage. Recipes for cawl vary by region and season in Wales, depending what is locally available. Some people use lamb but my mother always simmered beef bones with some meat on them for a couple of hours to extract their goodness; then she added shin or chuck that burbled for another hour or so, followed by all the vegetables. The soup would cook over a very low heat until we came home. While cawl can be eaten all together like a stew, in some regions (like my own) the broth is served first followed by meat and vegetables.

is a classic one-pot meal and the homely national dish, originally cooked in an iron pot over an open fire using the local ingredients: home-cured bacon, scraps of lamb, Swede [Editor’s note: turnip], potatoes plus the Welsh staple vegetables of leek and cabbage. Recipes for cawl vary by region and season in Wales, depending what is locally available. Some people use lamb but my mother always simmered beef bones with some meat on them for a couple of hours to extract their goodness; then she added shin or chuck that burbled for another hour or so, followed by all the vegetables. The soup would cook over a very low heat until we came home. While cawl can be eaten all together like a stew, in some regions (like my own) the broth is served first followed by meat and vegetables.

Leeks are the national symbol of Wales and frequently find their way into Welsh soups. If you dislike leeks you may be hard up for soup choices in Wales, for they are a favourite of Welsh cooks.

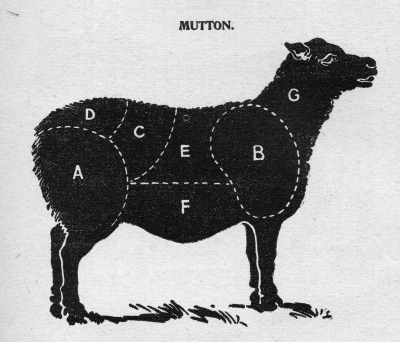

Welsh sheep are small and have a particularly good flavour when eaten young, as lamb. Salt marsh lamb, a distinctive Welsh specialty, grazes on marshland in coastal estuaries that supports a range of salt-tolerant grasses and herbs such as samphire, sparta grass, sorrel and sea lavender. In the various parts of the country where the lamb is raised as a speciality, notably around Harlech and the Gower Peninsula, the nature of the plants differs subtly by locale but all of them give the meat a buttery texture and rounded flavour that now is prized throughout Britain.

where the lamb is raised as a speciality, notably around Harlech and the Gower Peninsula, the nature of the plants differs subtly by locale but all of them give the meat a buttery texture and rounded flavour that now is prized throughout Britain.

Lamb may be the meat most often associated with Wales, but in the past it was eaten only on holidays. The pig was the source of the staple meat for a family, served fresh as pork or cured and served as bacon or gammon.

3. The Welsh prefigure the postmodern foraging movement.

In Wales, along with parts of Scotland and Ireland, an edible wild seaweed known as laver is gathered and processed commercially. The strangely named laverbread or bara lawr is sometimes called the Welsh caviar for its unique taste. When I was a child, laver used to grow on the rocks of the Gower Peninsula, especially around Penclawdd where it can be found clinging to the rocks at low tide. Laver is still gathered the old-fashioned way on the incoming and outgoing tides simply by reaching down and picking it up. Sensibly enough, it is washed and rewashed to rid it of sand, then boiled for ten hours until it resembles a pulpy mass when it is chopped into little pieces.

Even years ago laverbread was sold ready cooked in markets throughout Wales, but my mother always prepared her own from seaweed bought at either Penclawdd or Swansea market, which has the best laverbread to my taste. Stalls still sell laverbread in Swansea market (pick up a loaf of crusty Swansea bread to spread it on), and it is  available tinned. Highly prized in Europe, laverbread is a rich source of iodine, protein and Vitamins A, B, B2, C and D. It is eaten sprinkled with oatmeal, mixed with lemon juice and either spread on toast or fried in bacon fat, and also traditionally served with bacon for breakfast or supper. Its flavour is difficult to describe, a bit like salty spinach with a fishy flavour: Most definitely an acquired taste!

available tinned. Highly prized in Europe, laverbread is a rich source of iodine, protein and Vitamins A, B, B2, C and D. It is eaten sprinkled with oatmeal, mixed with lemon juice and either spread on toast or fried in bacon fat, and also traditionally served with bacon for breakfast or supper. Its flavour is difficult to describe, a bit like salty spinach with a fishy flavour: Most definitely an acquired taste!

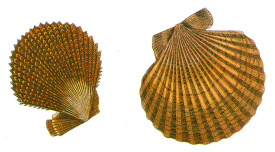

Cockles have thrived on the Gower since Roman times. They look to me like a tiny clam and taste somewhat similar. At low tide the women of the riverine villages traditionally went out on the sands carrying baskets to collect the cockles. They bent over to scrape the bivalves to the surface of the riverbed with short handled rakes and placed them in a riddle, something like a sieve, to rinse them and set the small ones back into the water. The gatherers then carried the harvest on their heads and loaded it onto donkeys for itinerant sale round the adjacent villages.

Today men who do the work use Land Rovers instead of donkeys and take their catch straight out of the water to the Penclawdd Shellfish Company’s factory right on the beach for immediate canning or pickling, but nothing else has changed. The local cockle industry in Wales would delight the newfound foraging movement.

Cockles sometimes are served with laverbread in Wales, and like the laverbread are definitely a taste that needs cultivating. My relatives from Birmingham used to come on holiday to Llangennith on the Gower, and we all used to go out at low tide to gather the cockles. We cleaned and cooked them ourselves to eat with vinegar.  Years later I am a convert to cockles and a favourite preparation may be found at Fairyhill, a superb hotel and restaurant on the Gower near Reynoldston. The kitchen deep fries local cockles as a starter and the rest of the food is equally noteworthy. They use locally produced meat, fish and vegetables including salt marsh lamb, Welsh black beef and locally caught fish and shellfish in addition to the cockles. When you visit Wales this place is a must.

Years later I am a convert to cockles and a favourite preparation may be found at Fairyhill, a superb hotel and restaurant on the Gower near Reynoldston. The kitchen deep fries local cockles as a starter and the rest of the food is equally noteworthy. They use locally produced meat, fish and vegetables including salt marsh lamb, Welsh black beef and locally caught fish and shellfish in addition to the cockles. When you visit Wales this place is a must.

The long Welsh coastline with its rocky cliffs and sandy bays supports a wide range of fish and shellfish, including prized crab, wild salmon and sewin (sea trout to the Sassenach) that is reflected in traditional Welsh recipes.

4. The loss of an iconic Welsh product.

Cheese making is an ancient tradition in Wales. Organic, unpasteurized and specialist cheeses always have been made from the milk of cows, ewes and goats. Caerphilly, a mild and crumbly white cheese, must be one of the better known Welsh varieties, along (at least within Wales) with Y-fenni from Abergavenny, a mature cheddar blended with mustard and Welsh ale. In the mountains and hills, where sheep or goats graze rather than cows, soft, creamy goats' and ewe's milk cheeses are made.

Ironically enough, true farmhouse Caerphilly, made in traditional rounds with natural rinds, survives only in the West Country of England and not in Wales, although similar cheeses are made in creameries within the Principality. Welsh readers of britishfoodinamerica, or readers who love Wales, should consider reviving the Welsh Caerphilly.

5. Specialisation (of ice cream) takes command.

With all this milk around it is hardly surprising that local ice creams are popular; most are made only in small amounts batches for local consumption. As a child it was a special treat to go for an ice cream on a Sunday afternoon at Joe's Ice Cream in Mumbles on the Gower. It has been in business since 1922. During the Second World War, they were not allowed to make ice cream due to rationing, so Joe spent his time perfecting vanilla ice cream, the only flavour that they now serve. With Joe’s own caramel, chocolate, fruit and hazelnut sauces to complement the ice cream, however, you will not lack for variety.

6. St David’s Day and traditional teas.

The Welsh and Welsh expatriots across the world remember their patron saint each year on 1 March. Fresh food traditionally is sparse at this time. The fishing season has barely started; it is too early for spring lamb, though hoggets (year old sheep) are mature and tasty; vegetables are limited, apart of course from leeks, the all season staple, and not even new potatoes are ready for the digging. A Welsh breakfast, however, was and is feasible, and a good way to start St David's Day: Sausages from the local butcher, dry-cured bacon, free range eggs, Penclawdd cockles and laverbread.  The day’s big feast should feature roast salt marsh lamb or, failing that, another good breed. The Welsh love teatime at four and St David’s Day is a good excuse for their indulgence. Traditional bara brith (the famous speckled bread of Wales); Teisen lap (pronounced tee-shen), a shallow moist fruit cake; teisen carawe, or caraway seed cake; teisen sinamon (cinnamon cake); and teisen mêl (honey cake) all are favourites for the tea table. Griddlecakes in great variety, including scones, pancakes, pikelets, cakes, breads, turnovers, oatcakes and famous spicy Welsh cakes oozing with rich Welsh butter join the baked goods for high tea.

The day’s big feast should feature roast salt marsh lamb or, failing that, another good breed. The Welsh love teatime at four and St David’s Day is a good excuse for their indulgence. Traditional bara brith (the famous speckled bread of Wales); Teisen lap (pronounced tee-shen), a shallow moist fruit cake; teisen carawe, or caraway seed cake; teisen sinamon (cinnamon cake); and teisen mêl (honey cake) all are favourites for the tea table. Griddlecakes in great variety, including scones, pancakes, pikelets, cakes, breads, turnovers, oatcakes and famous spicy Welsh cakes oozing with rich Welsh butter join the baked goods for high tea.

So whatever your ethnicity, stick a sprig of leek in your hat and take St David’s Day as a deserved excuse to brighten the gloom of muddy March with some Welsh comfort food.