Two Museum Exhibits & The Ministry of Food by Jane Fearnley-Whittingstall

The Museum of Modern Art and the Imperial War Museum seldom appear in the same sentence, but these contrapuntal institutions do share some common ground. The IWM too has an important collection of twentieth century art courtesy of the army War Artists program along with its trenches, tanks and planes; MoMA’s collections include industrial objects, even a helicopter, and both museums recently have mounted exhibitions about kitchens and food.

With these exhibitions we return to the notion of counterpoint.

MoMA visitors care in a rarefied way about the Importance of Art and in an obsessive one about their appearance. It is all a most serious business. The older urbanauts glide through cramped galleries in Armani; the younger crowd regards itself warily through the lens of self-conscious cool. If stylishly skirted art history students in cardigans coolly assess paintings at the Metropolitan Museum, at MoMA tattooed art students with breasts bobbing precariously amidst torn T-shirts slouch toward anomie, or perhaps a rave.

Its kitchen show, entendred ‘CounterSpace,’ purports to survey the development of modernist design as it relates to cooking, and the exhibition website devotes a workmanlike essay to the challenges that beset British housewives under rationing during the middle of the twentieth century. We were intrigued and therefore put aside longstanding prejudice to visit the font of modernist dogma on East 53d Street.

In reality, however, the exhibition gives the museum an opportunity to liberate something special from storage for the first time since its inception. It turns out that CounterSpace is not much more than a vehicle for displaying the Frankfurt Kitchen.

The little room is, as the notes to the exhibition indicate, compact and ergonomic but that hardly matters; as presented by MoMA the kitchen is not so much workspace as minimalist sculpture. No notes tacked to corkboard, no pictures on the fridge (no fridge), no onions on the counter or food of any kind, no dishes in the sink, no pots on the stove; no clutter here. Any artifacts, mostly dishes posted sparsely in cabinets, are props more than tools.

The little room is, as the notes to the exhibition indicate, compact and ergonomic but that hardly matters; as presented by MoMA the kitchen is not so much workspace as minimalist sculpture. No notes tacked to corkboard, no pictures on the fridge (no fridge), no onions on the counter or food of any kind, no dishes in the sink, no pots on the stove; no clutter here. Any artifacts, mostly dishes posted sparsely in cabinets, are props more than tools.

This reminds the Editor of her art history textbook, in which a prominent professor described nineteenth century architecture in terms of art but not purpose. He did not assess the impact of technology on design and, for example, scoffed at the Victorians’ unfathomable addiction to the glazed brick facade. They, however, had realized something that he did not; glaze is not porous, and you therefore can wipe from it the soot of industrial cities that blackens everything else.

The Frankfurt Kitchen has remarkable elements (no glaze), not least its inbuilt bank of fifteen aluminum storage containers, each dedicated to a discrete ingredient, that alone would be worth MoMA’s dizzying tariff.

They are descended from World War I cartridge boxes; both implements were made by the same company, which pushed out and opened one end of the box and affixed a handle to the other, modifying its military design for domestic use as a storage scoop.

The kitchen has many such delights, including a window counter that doubles as desk (but who would have used it for that in so small a space to cook?) and walls of soothing deep grey to help hide the dirt (but that is not noted). It is stunning design, and stunning that Weimar mass produced thousands of these rooms for installation in housing projects between the wars. It would be nice to see what people actually did in, and to, them.

MoMA approves of their creator’s credentials. Grete Schutte-Lihotzky was one of the first female architects to practice in Germany and something of an iconoclast, mistrusted by Nazis, Reds and Red Baiters alike. She did not do much after the war because the Communists did not let her. Her gender is a stated trope of the show and we are not to forget that the domestic kitchen is the woman’s sphere:

“Prominence is given to the contribution of women throughout the exhibition, not only as the primary consumers and users of the domestic kitchen, but also as reformers, architects, designers and as artists who have critically assessed kitchen culture and myths.”

All of this would be a bit of a bore, if in fact CounterSpace did any such thing, and outside of the Frankfurt Kitchen, the exhibition does not work. Many artifacts are not the creation of women; the paintings and reels of performance art have scant relation to the stated theme; and the museum fails to make its case that the film Point of No Return featuring a sexpot assassin addresses this ‘culture’ and these ‘myths’ simply because a gunfight rages through the commercial kitchen of a restaurant. MoMA might as well have cited Jurassic Park, but never would stoop so low, artistically speaking: Doesn’t a velociraptor romp through a similar room trying to eat children?

Objects in the exhibition are shelved in rough chronological order, but randomly; fanciful items jostle workaday implements because MoMA used what it had on hand from its collection, which while formidable hardly focuses on the kitchen arts. There are jewellike salt and pepper shakers by William Lescaze of PSFS fame (not a woman) and an ingenious counterweighted French measuring spoon from 1955 that fits on its stand to form a fulcrum scale (designer and manufacturer unknown). We wanted one.

The curators, however, are not cooks. A pair of steel darioles from the 1930s, for example, is described instead as “cups,” and the exhibition never does tell us what all those Frankfurter housewives thought of their little modernist kitchens. Do any remain in use?

One wall holds a handful of propaganda posters printed by the British Ministry of Food in World War II to justify rationing and decry waste. They are spectacular and do not fit in this show. To the Editor’s surprise, no cookbooks appear, not even the Futurists’ surreal manifesto nor anything molecularly modern. The slight exhibition catalog is a disappointing afterthought.

If MoMA peers from on high, the Imperial War Museum plays in the mud, quite literally; it has that squalid, scary trench from the Western Front. The crowd here in Southwark is different from the one in Midtown Manhattan. Fashion is not to the fore. Children tear through the big galleries and touch the big artifacts, tanks and field guns among them; they can sit in the cockpit of a Lancaster and the shop is full of toys. Families visit the museum together. There are young couples too, and geezers in rumpled sweaters. This is an unpretentious and vibrant place despite the fact that its name encompasses three of the more unpopular words in the contemporary lexicon.

If MoMA peers from on high, the Imperial War Museum plays in the mud, quite literally; it has that squalid, scary trench from the Western Front. The crowd here in Southwark is different from the one in Midtown Manhattan. Fashion is not to the fore. Children tear through the big galleries and touch the big artifacts, tanks and field guns among them; they can sit in the cockpit of a Lancaster and the shop is full of toys. Families visit the museum together. There are young couples too, and geezers in rumpled sweaters. This is an unpretentious and vibrant place despite the fact that its name encompasses three of the more unpopular words in the contemporary lexicon.

Perhaps its wonderful but politically incorrect name explains the plangent new motto of the museum, its none too subtle argument for relevance: ‘War Shapes Lives.’

The IWM by no means limits its programming to the implements of war. The art collection is extensive and superb, displayed in serene galleries at the top of the building which, as nobody can resist noting, once housed Bedlam, the hospital devoted to depravity. The collection includes paintings by Nash, Spencer and other British luminaries who served as official War Artists, but few of them glorify combat. Instead they depict suffering and fear; gassed Tommies at the front, Londoners sheltering from the Luftwaffe in the Underground.

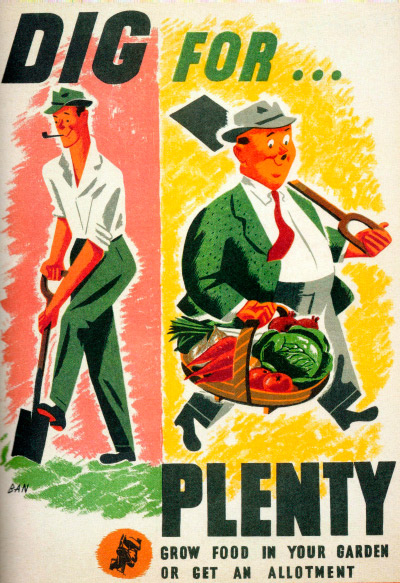

The Imperial War Museum’s own culinary exhibition, “The Ministry of Food,” just concluded. Like MoMA, the IWM included brilliant British wartime posters exhorting people to eat indigenous foods, innovate in the kitchen, in part by trying unfamiliar items, and cut waste. IWM had a lot more of the posters, however, and they were considerably more than an afterthought in an exhibit designed “to show how the British public adapted to a world of food shortages” created by war and its aftermath from the imposition of rationing in 1939 until its repeal in 1954. Unlike “CounterSpace,” this exhibit succeeds in its stated purpose by including austerity recipes, ration coupons, official “Dig For Victory” leaflets and little “War Economy Standard” cookbooks among the artifacts.

In something akin to period rooms, the displays also included a wartime grocery shop, greenhouse and kitchen with its stocked larder. A typically middle class house as it stood during the Second World War remains on permanent display within the museum. The kitchen is worlds away from its Frankfurt counterpart in New York: It does not aspire to art; instead it is full of the mess of life. This is how they lived, in the foreign country of the past, in the time of peril. There are scraps of food and ration books and aprons and the implements of daily life.

Of course there is film, now obligatory for all installations, but unlike at MoMA the selection is apt. Newsreels set the era and short features on making do from the Ministry of Food that were seen by millions touch the heart of the exhibit’s purpose. The mission here is hardly MoMA’s, and it is not as if either one is more worthy or appropriate. It is just that the Southwark museum fulfills its particular mission better.

The Imperial War Museum considers its remit to encompass not only the preservation of artifacts, an important enough purpose in its own right, but also to convey the experience of war both at home and in the field since 1914, and the institution takes its educational function seriously. It is a teacher of popular history, but popular history in the best rather than debased sense found on the History Channel.

The book of the same name by Jane Fearnley-Whittingstall published in conjunction with “The Ministry of Food” reflects both the strengths and weaknesses of that approach. It is, according to the museum’s publicity release, “a practical guide to help modern families survive the credit crunch.” Historians, however, should not strive too much for relevance. When they do so, their judgment may be influenced by current preoccupations more than sound analysis, and the effort to link the past to the present often becomes strained.

In Ministry of Food the effect is jarring. For example, Mrs. Fearnley-Whittingstall ends her otherwise excellent chapter that describes the successful wartime effort to grow more food in Britain by forcing an analogy that trivializes the experience of conflict: “In the 21st century our wars are against obesity in children and adults, against waste and against financial constraints.” (Ministry 20) Elsewhere she explains that “[t]oday we still need to be as flexible in our shopping as wartime housewives” before undermining her premise: “The difference is that today we don’t suffer from rationing or scarcities.” (Ministry 128)

Other attempts to draw parallels sound strained. The revivalist recipe for stuffed lamb is not so retro after all: It is “a far cry from the wartime version.” Offal was not rationed and therefore became an expedient, but a recipe for kidneys relies on red wine and canned tomatoes, both unavailable to wartime cooks. (Ministry 115, 159) Fearnley-Whittingstall also includes a recipe for carrot cake because she likes it, but “British wartime cooks seem not to have known about carrot cake.” (Ministry 124)

Other attempts to draw parallels sound strained. The revivalist recipe for stuffed lamb is not so retro after all: It is “a far cry from the wartime version.” Offal was not rationed and therefore became an expedient, but a recipe for kidneys relies on red wine and canned tomatoes, both unavailable to wartime cooks. (Ministry 115, 159) Fearnley-Whittingstall also includes a recipe for carrot cake because she likes it, but “British wartime cooks seem not to have known about carrot cake.” (Ministry 124)

Fortunately these infelicities are in exceptions to the point of The Ministry of Food. It is not much of a guide to modern thrift but rather an engaging social history of how rationing and the victory garden affected ordinary people. Fearnley-Whittingstall was a good choice to undertake the project; she remembers the experience herself, demonstrates an easy grasp of her subject and writes in a style at once authoritative and accessible. All of us should aspire to it.

If someone were to tell the Editor that a story of agricultural management could be thrilling, she would scoff and would be wrong. Fearnley-Whittingstall has an eye for fascinating facts too. Despite the failure of the Royal Navy to plan for fighting the submarine threat to Britain’s dietary lifeline, civil servants elsewhere were ready. Before the day that the nation declared war ended, “every War Ag committee had received a telegram from the minister of Agriculture. Each county was set a target” for increasing the production of food. (Ministry 17) Flowers disappeared in favor of food crops, “huge tracts of bog, fen and moorland, never before cultivated, were brought into production” and ancient grazing commons ploughed up for the first time in a millennium. (Ministry 19-20)

“Between 1939 and 1944, 6.5 million new acres had been ploughed, and although 98,000 farm workers had been called up, 117,000 women had replaced them. Between 1939 and 1945 food imports were halved and the acreage of land used to grow food crops increased by 80 per cent.” (Ministry 20)

Footnotes or other access to the sources of this kind of information would have been nice, especially because the bibliography is inadequate but the index is superb, a rarity these days.

The concise chapter on “How Rationing Worked” is among the best that has been written on the subject, whether by a popular or academic historian, and fortunately the attempts at currency are frequently tacked like an afterthought to the end of a section of good analysis and therefore not overly intrusive. There is not a shred of posing or pretence; Fearnley-Whittingstall has chosen her reminiscences well and without sentimentality. She likes Spam.

The layout of Ministry of Food is as striking as its prose, the recipes are clear and good, and the calendar of instructions for growing all kinds of produce is so straightforward and enticing that even the Editor is tempted to get her hands dirty.

We’ll take a leek...

We’ll take a leek...

The reproductions of wartime posters (including the handful at MoMA), pamphlets and other graphics, most of them from the IWM collections, are both comprehensive and superb. The publisher even has gotten the color tints, so different in the 1940s from today, right. As all of this indicates, however, The Ministry of Food is not an exhibition catalog. It is better than that. The recipes, history and artwork reinforce one another and enhance the authenticity of the experience. Wartime songs and jokes from Punch also help set the scene. And by tying the show’s displays to a larger theme, the book exemplifies the kind of living history pioneered so successfully by James Deetz at Plimoth Plantation.

Cook the authentic recipes to comprehend that foreign country a little better, and cook the inauthentic ones too, just for fun. Read the text of this book before you cook and revel too in its visual delights, for the illustrations alone are worth the price notwithstanding its considerable other strengths.

The catalog to “CounterSpace” is available at the MoMA shop on West 53d Street in Manhattan and online from the museum and various internet retailers. The Ministry of Food unfortunately is not published in the United States, but both new and used copies are for sale at www.abebooks.com and other online sources.