It left a bad taste: The Editor considers The Taste of War: World War Two & the Battle for Food by Lizzie Collingham

A psychiatric disability called Stockholm Syndrome often afflicts hostages, particularly those who have suffered torture or other mistreatment at the hands of their captors. These unfortunate prisoners become besotted with their tormentors.

Writers, and particularly writers of history, are at risk of a similar syndrome in which they become sufficiently immersed in their chosen subject to endow it with undue significance. That is understandable, for after spending years to research a topic they lose perspective on its relation to the wider world. The Taste of War is a cautionary example of the malady. In it, Lizzie Collingham insists that concern about the supply of food caused the Second World War, and the success or failure of the belligerents to meet that concern determined the outcome. Her thesis is not convincing.

This failure is all the more disappointing because Collingham’s previous book, Curry: A Biography, is an insightful and delightful meditation on the development of Raj cuisine. Slivers of the politically correct in the form of obligatory jabs at imperialism mar Curry as a minor irritant but do not much impact the overall appeal of the text. Collingham properly accepts the notion that what we understand as authentic Indian food is in fact a synthesis of east and west that would not have been possible without the British and their fascination with the food they found on the subcontinent. As a bonus, she intersperses her analysis with a number of lively and workable recipes.

We have no such luck with The Taste of War. Collingham attempts to advance her thesis by forcing and repeating the argument, and her examples of how food preoccupied military strategists fall flat. For example, Collingham argues that an overarching concern about feeding the German population always had obsessed the Nazi hierarchy and drove its decision to launch Barbarossa into the Soviet Union. She cites the “overlooked Herbert Backe” and the “Hunger Plan” he formulated to starve the population of the Ukraine and repopulate the region with Germans as proof, while conceding not only that the plan “was never fully implemented” but also that both Hitler and Goering were bored by Backe and discussion of agricultural planning for the conquered eastern territories. (Taste 32, 34) It simply was not that important to them.

A corrosive racial theory rather than the food supply dictated Nazi policy on the eastern front. The Nazis could just as easily have contemplated the same fate for the French, but they were not Slavic and therefore not ‘subhumans’ who deserved extinction according to Nazi doctrine. And it is belaboring the obvious to declare that “[n]either Backe nor the National Socialist attitude toward food was harmless” when their attitude about everything was harmful. (Taste 32)

Collingham writes that “[t]he National Socialists began the Second World War well aware that a short war was essential for success and that only during a short war could adequate civilian rations be guaranteed.” (Taste 34) In fact, the Germans required a short war for manifold reasons, not least their inability to match the industrial capacity of the United States, lack of natural resources including petroleum and the failure to develop a strategic air arm to complement the formidable tactical skills of the Luftwaffe.

Hitler himself dominated the decision to wage war, and left logistics, including the supply of food, to others or ignored logistical realities altogether, with predictably disastrous results for his armies. Ideology trumped everything. It made no military sense to tie down so much manpower to exterminate ‘undesirables’ or to garrison Norway. It made no strategic sense to divert divisions from their drive on the priceless oilfields of the Caucasus to besiege a city on the Volga, and if the city had borne any name other than Stalingrad Hitler would not have decided to invest it. He simply wanted to gain a moral advantage from destroying a place named for his enemy.

Food ran short during the siege of Stalingrad, and the surrounded German Sixth Army suffered for it, but everything else ran short too, including fuel, ammunition, artillery, air support and supply, even the armor required to break through in relief. Soldiers who began their attack in summer denim never received winter clothing; vehicles were never modified to operate in the extreme cold. The Sixth Army did not starve but soldiers died of exposure and it did cease to function as an operational formation. Nor did the German population lack for food during the war. Millions of Russians and their subject peoples did starve, however, and they won it.

Collingham also claims that the British prevailed in defending India and retaking its other Asian possessions from the Japanese in large measure because they learned to destroy their own food supplies during retreat instead of allowing them to fall into the clutches of Japanese troops. This too is at best a debatable point that belabors the obvious. All forces seek to deny giving resources to their opponents; the French scuttled a fleet at Toulon rather than surrendering it to the Kriegsmarine. British forces concentrating at Imphal and Kohima in 1944 did not learn to destroy the supplies they could not carry; unlike the hapless defenders of Malaya three years earlier, who did inadvertently feed their opponents, they retained their operational coherence.

Far from harboring an obsession with food as a military necessity, the high command of the Japanese Imperial Army disdained bothering with its provision. Totalitarian regimes seldom consider the welfare of their own people, and the leadership of wartime Japan was no exception.

Japanese doctrine relied on the capture of enemy provisions to sustain campaigns. The undersupplied armies marching on Imphal and Kohima in what one historian has called the longest and largest suicide raid in history lacked not just food for a potential retreat but just about everything else required for a military operation. If they failed to take the British strongholds and supply dumps as ordered, then they deserved to die.

The problem with The Taste of War runs deeper than its determinative bias. Collingham is no military historian, and proves neither conversant nor comfortable with the complexities of mechanized warfare, which can cause difficulty in chronicling the progress of a global twentieth century conflict. She is heavily reliant on secondary sources for her military narratives and, ordinarily an assured writer, gives descriptions of campaigns and battles that come across as canned.

Military exigencies do not fire Collingham’s imagination and strike her primarily as impositions on civilian populations, which in reality were reliant on military success for their survival. It bothers her that the United States diverted shipping from the carriage of food to Britain for the invasion of North Africa, a campaign that she appears to consider little more than window dressing carried out to appease Stalin, when in fact it then was the largest, and longest range, amphibious operation ever attempted.

Problems arise even in the realm of food itself. Collingham does not much like the British War Cabinet and, at least in The Taste of War, loathes the British Empire. She therefore has appointed herself a scything revisionist determined to impair the reputation of iconic figures, not least Woolton and Churchill.

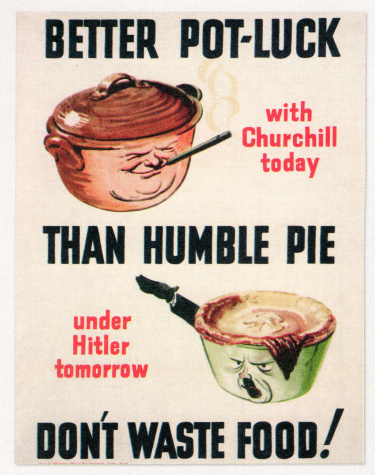

By other accounts Lord Woolton is a fascinating and sympathetic figure with “a strong social conscience.” According to Nicola Humble, for example, “April 1940 saw probably the defining moment in the story of food and the war: the appointment of Lord Woolton as Minister of Food.” (Humble 84) Woolton took speaking lessons and broadcast a series of radio talks called the “Kitchen Front” over the BBC. One of his “major achievements was the great affection he seems to have aroused in a large section of the British public.” (Humble 92) As Jane Fearnley-Whittingstall notes, imposing and enforcing the restrictions of rationing “are unlikely to endear one to the public, yet he was universally trusted and regarded with affection. He became known to the public as Uncle Fred.” (Ministry 85)

These are not isolated views. According to the DNB, Woolton’s

“biggest triumph was getting people to accept rationing as not only necessary and patriotic but also equitable and efficient. He soon became, next to Churchill, the most popular and identifiable cabinet minister. Woolton took the opportunity to implement positive social reform when he began the provision of milk to schoolchildren and orange juice to expectant mothers.”

Collingham takes a different slant. She gives Woolton grudging credit but in her hands he also is an arrogant bungler who referred “condescendingly” to his radio audience and “failed to pay attention to actual food availability in America.” His “inflated food import quota” from the United States was a “definitely unwise” decision. It went unmet and therefore “did nothing to improve the protein content in the British diet” although Collingham dissonantly concedes that he made up the difference “by increasing imports from Argentina.” (Taste 108-09, 366) The rapid expansion of wartime agriculture is dismissed as “a modest success” even though yields of staple crops doubled. (Taste 96)

Collingham dismisses Woolton’s concern over U-boat sinkings and minimizes the threat to British survival posed by the Battle of the Atlantic, yet also describes a resultant “shipping crisis.” (Taste 105, 115) His rationing system, which others (including, as noted, the DNB) have credited with an egalitarian cast and a dramatic improvement in the diet of the poor, was “deeply inequitable.” His memoirs are self-aggrandizing. (Taste 115, 362)

We do not see much about Churchill from Collingham but what we do glimpse is not pretty. She decries his unwillingness “to feed European civilians behind German lines” and quotes with approval Herbert Hoover’s assessment that he was “a militarist of the extreme school who held that incidental starvation of women and children was justified.” (Taste 167, 177) Postwar food shortages “made something of a mockery” of a speech that he gave--in the considerably different conditions of 1940.

Churchill (like American strategists) was so “determined to achieve victory” in the North African campaign that “he was prepared to compromise the quality of civilian imports arriving in Britain (Taste 105),” which would not seem a prohibitive price considering the fact that nobody went hungry eating the admittedly monotonous diet that developed under rationing. “He is said to have claimed” and “said to have thought” terrible things about India; “[p]rejudice and dislike seem to have” determined his policies toward the Raj. (Taste 145, 151) Many of Churchill’s attitudes may have been deplorable, but so much resort to speculation does not give her reader confidence, and most historians have managed to find some redeeming qualities in him.

“The war intensified the exploitative nature of colonialism,” according to Collingham; elsewhere she declares that “groups within colonial societies… profited greatly from the growth of war industries.” (Taste 120, 121) It is both unnecessary to point out that “Britain was never as ruthless as Germany and Japan in its exploitation of its empire’s resources, nor did it engage in deliberate acts of murder or dispossession” and speculative, even contradictory, to claim that “an unspoken food hierarchy” did just that. (Taste 124)

Collingham provides considerable detail about the privation in Mauritius that was caused by the British diversion of shipping, and understandably decries the Bengal famine of 1943-44, which may have killed more than a million and a half people.

She castigates Churchill for the British response to the crisis, and yet notes that Indians themselves contributed to it. Collingham does not, however, disclose that the Ministry of Food extended rationing, which caused considerable privation to a British population that had been at war for six years, from the end of the war until 1948 in an effort to redirect foodstocks and prevent starvation in Asia.

Elsewhere in the empire, Collingham finds it astonishing that over 100,000 Australians volunteered for service following “Britain’s ignominious withdrawal from Dunkirk.” At the time, however, Dunkirk was hardly considered shameful. The small British Expeditionary Force had fought well and the extrication of the army was universally perceived as a miraculous deliverance. It caused such exhilaration that Churchill found it necessary to remind his people that “wars are not won by evacuations.”

Only Comintern could join Collingham in declaring unequivocally that a “spirit of sacrifice undoubtedly permeated the entire wartime population” of the Soviet Union when the political cadres prodding combat troops into battle at the point of a bayonet and widespread executions may have provided additional motivation. (Taste 345)

The proliferation of factual errors further undermines confidence in The Taste of War. To cite just three: Radar did not ‘deny submarines their invisibility;’ it forced them to become invisible by submerging; the United States never has had a “Ministry of Agriculture;” and North Africa was not “the only front on which the British and American armies engaged in combat with the Wehrmacht” until June 1944. (Taste 126) There was that small matter of the Italian front too on which, incidentally, Rome fell during June of 1944.

All of this said, the subject that Collingham addresses, and the creative focus on the role of food in war, are fascinating. They deserve better treatment.

Sources:

Lizzie Collingham, The Taste of War: World War Two and the Battle for Food (London 2011)

Jane Fearnley-Whittingstall, The Ministry of Food: Thrifty Wartime Ways to Feed Your Family Today (London 2010)

Nicloa Humble, Culinary Pleasures: Cookbooks and the Transformation of British Food (London 205)

Michael D. Kandiah, “Frederick James Marquis, First Lord Woolton,” Dictionary of National Biography online (May 2008; accessed)