Wartime Cookery, featuring not only imposters but also erotomania

During the Second World War, all governments worried that food shortages would cause social unrest and strategic catastrophe. Strategic setbacks related to food supply and starvation itself would in fact plague a number of combatants and their victims both during and after the war.

Britain faced a particular challenge to feed its population for several reasons. It could, or would, not control hungry masses by coercion like the Soviet Union or Axis countries, and unlike them did not loot its neighbors. Unlike the United States, Britain lacked a vastness of arable land to produce reliable agricultural surpluses.

Instead, in a classic case of comparative advantage, industrial Britain had been a net importer of food for decades before the onset of war. This wartime disadvantage was compounded because so much of its food arrived by sea. In 1939, Britain imported more than sixty percent of its foodstuffs, a number that understates the nation’s reliance on the sea lanes because farmers also relied on imports of winter feed for their animals. (Ministry 20)

1. In the country.

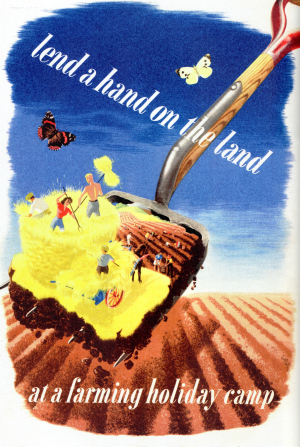

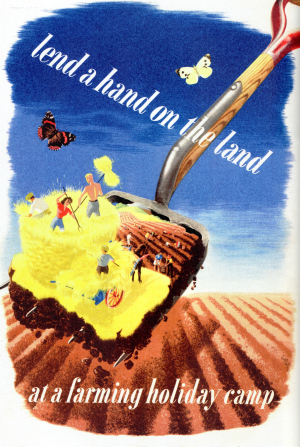

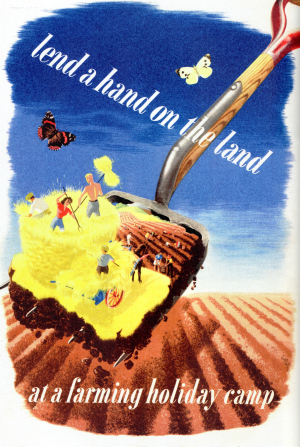

To meet the problem on the home front, Britain nationalized control and production of agriculture.  Nonessentials like flowers were plowed under, wetlands drained and scrubland cleared. The Ministry of Food set quotas for crops and livestock, imposed price controls and, in 1940, food rationing. Grains feed more people per acre than dairy herds, dairy feeds more people than meat; wartime production of grains therefore soared at the expense of livestock, and fresh milk became less plentiful.

Nonessentials like flowers were plowed under, wetlands drained and scrubland cleared. The Ministry of Food set quotas for crops and livestock, imposed price controls and, in 1940, food rationing. Grains feed more people per acre than dairy herds, dairy feeds more people than meat; wartime production of grains therefore soared at the expense of livestock, and fresh milk became less plentiful.

By 1944, Britain had added 6.5 million acres of farmland; by 1945, the amount of land under cultivation had increased eighty percent from prewar levels and imports of food cut by half. The production of oats increased by fifty eight percent; the production of barley, potatoes and wheat each doubled. (Ministry 20)

According to Lizzie Collingham, this increase was due more to long hours of sheer labor than horticultural or technological innovation, and she has an argument. (Collingham 89-90) The native agricultural workforce appears to have increased by only about a sixth between 1939 and 1944, when 117,000 recruits to the Women’s Land Army replaced 98,000 farm workers lost to conscription, but seasonal labor, mostly students and faculty during summer time, and over 50,000 prisoners of war also eventually worked in British fields. (Collingham 95; Ministry 20) Despite Collingham’s doubts, however, technology may have helped too; for example, the number of tractors employed in British agriculture increased from some 56,000 on the eve of war to 203,000 in 1946. (Wilt 226)

This increase in self-sufficiency had the side effect of decreasing the variety of fruit and vegetables available in Britain. Its climate is comparatively cold, so that while root vegetables may thrive and orchards may yield, the growing season for ‘luxury’ items like asparagus, tomatoes or fruit other than apples is short and sometimes precarious. The bumper crops harvested on a wartime footing bred a numbing monotony at the table.

Collingham, a rather strident revisionist, argues that this “restructuring of agriculture was a modest success,” nothing more. (Collingham 96) By any statistical measure, the transformation of the British landscape was in fact a considerable achievement, but she is right that imports, predominantly of processed proteins, still accounted for a little more than half the calories (as opposed to bulk) consumed in wartime. Even without battle losses, shipping space remained scarce for most of the war, so that “condensing food was the key to keeping Britain fed.” (Collingham 101)

2. On board ship.

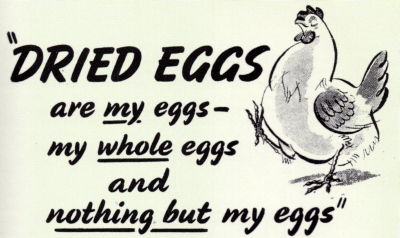

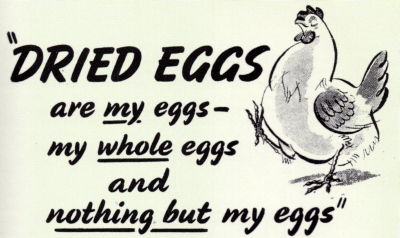

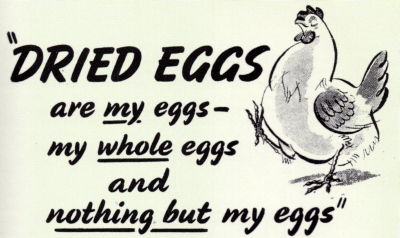

The volume of meat products was reduced by “de-boning, telescoping and canning;” dried egg powder displaced twenty percent of the volume required by the real thing and boasted an infinite shelf life along with its terrible taste. “A variety of other unspeakable powders and pastes was manufactured” as well. (Collingham 100) Many of the processed meat products (some dried, others frozen) were little better, and the processed cheese substitute from a tube was nearly inedible, “a soapy wartime product.” (Garfield quoted in Collingham 100) Despite all this, however, it is a reliable trope to observe that the British people, and in particular the poorer among them, were better fed in terms of nutrition during the war that at any time since the onset of the urban industrial revolution. As Collingham notes, however, “if the British did not sacrifice the energy content of their food they did sacrifice taste.” (Collingham 100-01) Wartime food, with few exceptions, was no fun.

The volume of meat products was reduced by “de-boning, telescoping and canning;” dried egg powder displaced twenty percent of the volume required by the real thing and boasted an infinite shelf life along with its terrible taste. “A variety of other unspeakable powders and pastes was manufactured” as well. (Collingham 100) Many of the processed meat products (some dried, others frozen) were little better, and the processed cheese substitute from a tube was nearly inedible, “a soapy wartime product.” (Garfield quoted in Collingham 100) Despite all this, however, it is a reliable trope to observe that the British people, and in particular the poorer among them, were better fed in terms of nutrition during the war that at any time since the onset of the urban industrial revolution. As Collingham notes, however, “if the British did not sacrifice the energy content of their food they did sacrifice taste.” (Collingham 100-01) Wartime food, with few exceptions, was no fun.

3. At the stove.

If expedience replaced flavor in much of wartime food, unpredictable supply added another level of dislocation. Even during the blitz, conversation on the home front therefore

“tended to turn on.... food: what was permitted, what was to be had, what was not permitted and where this was to be had and at what cost, what was not to be had and how so-and-so had had it. When bombs were not descending, or ruins being searched for household goods before the demolition men could get at them, food talk often beat bomb talk.” (Macaulay 93)

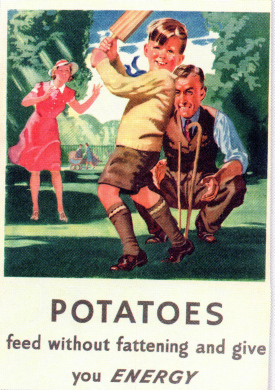

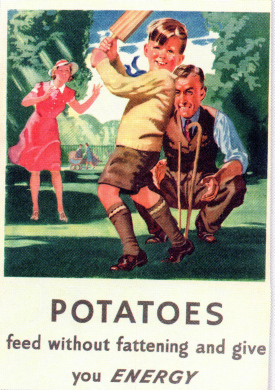

The Ministry of Food, especially in the person of Lord Woolton, whom we will appreciate in the lyrical, was neither unaware nor unsympathetic, and met the discomfiture head-on through a peculiar British combination of propaganda and homely hints. These appeared through a number of media including the famous and beautiful posters promoting healthy and frugal eating, radio broadcasts, ‘Dig for Victory’ leaflets and any number of wartime cookbooks produced “in complete conformity with the authorized economy standards.

Much of this effort entailed promotion of the war effort through shared exertion and sacrifice, but some of it attempted to meliorate the hardship. The cookbooks served both functions. They all measure less than eight inches high by five wide and seldom exceed 130 pages; their paper is thin and has become brittle seventy years on. At first it may seem dissonant to divert scarce resources to print cookbooks during a national emergency, but the government encouraged publication of the little volumes, and printed some of them itself, in an effort to help the public cope not only with unfamiliar and frequently unpalatable products, but also with the sheer dullness of wartime sustenance. Fats of all kind, for example, were scarce, and plain boiled food gets tedious fast.

4. From the books.

Many wartime cookbooks demonstrate that a certain level of imagination is a dangerous thing. Scattered throughout them you will find mock chops, duck, fish pie, flan, game, goose, whitebait, marzipan and other ersatz substances, sculpted from potatoes, artichokes, carrot, soy, even oversized zucchini and other vegetables. They are best left undescribed and, like the ‘Wild Turkey Surprise’ made from dynamite that Bugs feeds the Tasmanian Devil to blow him up, undisturbed. If, however, it is easy to mock all this wartime mockery, not much has changed, at least in some circles. Vegetarians trying to slake their bloodlust without guilt can find multiple brands of fake burgers, fake sausage, even fake bacon and “tofurkey,” frequently fashioned from soybeans. These awful substitutes would have delighted the Ministry of Food.

One of its publications, Food Facts for the Kitchen Front, opens with a blast of unabashed exhortatory propaganda:

“In these days, when we are all beginning to concern ourselves with essentials and to discard the things that do not matter, it is necessary to remember these two facts:

1. What we can get is good for us.

2. A great deal of what we cannot get is quite unimportant.” (Food Facts 6; emphasis in original)

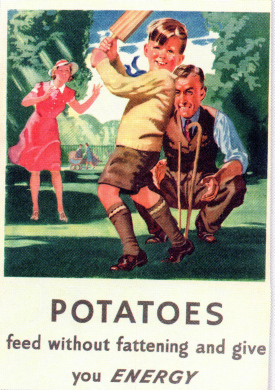

If, however, the Ministry of Food teeters on bombast, and betrays a pathological obsession with potatoes, it manages not to slip into the precipice. Its patriotism is not unbound and the Ministry cannot resist a wry joke. Thus the admission of received culinary Anglophobia: “It was once said that English cooking demanded a Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Vegetables.” (Food Facts 10) In the new dawn of healthy wartime eating, the SPVA would become superfluous because an innovative cuisine could sweep the archipelago. This novelty, however, often was more apparent than real, for as Nicola Humble has noted, many traditional dishes, both British and foreign, were simply cast from their historical tether and given new names.

If, however, the Ministry of Food teeters on bombast, and betrays a pathological obsession with potatoes, it manages not to slip into the precipice. Its patriotism is not unbound and the Ministry cannot resist a wry joke. Thus the admission of received culinary Anglophobia: “It was once said that English cooking demanded a Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Vegetables.” (Food Facts 10) In the new dawn of healthy wartime eating, the SPVA would become superfluous because an innovative cuisine could sweep the archipelago. This novelty, however, often was more apparent than real, for as Nicola Humble has noted, many traditional dishes, both British and foreign, were simply cast from their historical tether and given new names.

Food Facts imagines that a soup of cabbage, potato, milk and water--essentially colcannon thinned for a time of scarcity--may masquerade as “Creole Soup.” Similar wan attempts to render the humdrum exotic pop up throughout our genre, not least in the titillating work of Josephine Terry, who sounds like she bounces about with a coat hanger upside down in her mouth. In Food Without Fuss she includes a “New Orleans Bake” made from parsnips and beef dripping, which only could appear in the Crescent City of an alternative universe. She is, however, like the object of Ignatius’ desire in A Confederacy of Dunces, one saucy minx and, like Myrna herself, bookish.

Terry also is the Total Woman of wartime.

“To our delight we housewives of to-day find ourselves in a somewhat exalted position. Each time we serve a meal we stand in the limelight, facing an audience of men and children--with large appetites and small rations.

“We know their health and happiness depend on us, up to a point. But what a point! Everyone has become wise about the merits of a good meal, and never before have we received such wholehearted appreciation.

“We like it.” (Fuss 11)

When not busy channeling Hank Williams and Lord Copper’s stooge, would this exhibitionist greet that man wearing ought but apron, martini in hand? Perhaps not when the kids were about.

Elsewhere Terry entreats the sisterhood to persevere. In her version of ‘Lie back and think of England’, entitled “Your Bit--Well Done,” she reminds them that

“We all know that some of our good fortune has come to us through something we disliked very much at the time, through happenings, unpleasant or tragic, which proved later on to be good for us.

The present food shortage may well be such a happening. Hard to endure at times, it makes us aware of many new tastes and provides thrills which otherwise we should have missed.” (Future 7)

Terry applauds experimentation, and finds it strange “that a people as fond of flowers…. might have never paid attention to edible plants which is due to them” but for the inhibitions released by the pressure of war. (Future 40)

“I’ve got an edible plant for you.” or “Would you like to nibble my knockies?”

There is a paean to The Cosy Box, “one of those humble things in life which prove to be invaluable.” Regular use of this “nest” empowers its owner. “The Cosy Box enables us to leave the house cheerfully for a long stroll along the river, for an excursion, in pursuit of an invitation….” (Future 94-95) It also allows its owner to simmer stews with very little energy, like an improvised precursor of the crock pot.

Terry is not snobbish about her companions in the kitchen; even homely soya takes her breath away. “This little word, brief and musical, heads one of the most sensational stories of the world’s hidden treasures.” (Fuss 143)

As melancholy may follow climax, however, these little books betray an inadvertent poignancy. Terry may enjoy nibbling velvety buds, but is practical enough to recognize that sometimes a girl has no choice but to look for help from unattractive sources. Her recipe for ‘Gold Diggers’ Soup made from flour and dried egg does the nutritional trick but packs no thrill. (Fuss 143)

Sometimes she relies on fantasy to get the job done. One chapter of Food Without Fuss is devoted to “Make-Believe Dishes,” which, despite expectations, do not include the mock items, although there is a recipe for “artificial gravy.”

The Ministry of Food is frank enough to scatter recipes with little admissions of failure to satisfy its women. The instructions for a ‘Dutch casserole’ (in terms of authenticity see “Creole Soup”) call for “[a] few dried plums, if available;” others, for boiled vegetables (the ‘Autumn Platter’) call for a cover of grated cheese, “if you have it” before specifying “about 2 dessertspoons or what can be spared” and a recipe for soup suggests the addition of “a little milk when it can be spared.”(Facts 40, 41, 102)) Others follow listed ingredients with an apologetic “if possible.”

The otherwise optimistic Terry also uses “if possible” as a trailer and recognizes elsewhere that some desires may be unfulfilled. In a recipe for ‘Delicate cups’ she suggests anointing the delicate flesh with gelatin “and, if you can get it, a few drops of wine or brandy.” Her ‘Goulash Knockies’ benefit from a squirt of “meat extract” and “if you can get it, any kind of tomato sauce or juice or puree.” (Future 14, 17)

Ambrose Heath also makes allowances for scarcity in his wartime recipes. They variously recommend the addition of cheese, milk or onions, but only “if you can.” (See, e.g. Kitchen Front 30-31, 34, 35, 51-52)

5. An unfortunate future.

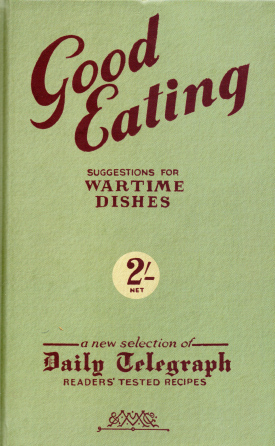

The scarcity of former staples and reliance on processed protein products encouraged authors to create ghastly recipes and cooks to acquire unfortunate habits. According to Nicola Humble, the “combination of limited ingredients and a licence to experiment meant that the cookbooks of the Second World War contained some of the most unpleasant food of the last 150 years.” (Humble 101)

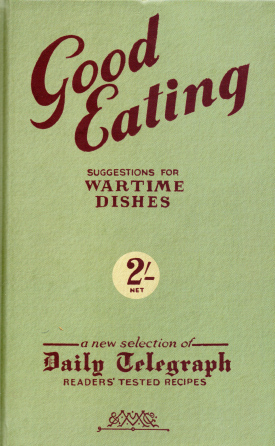

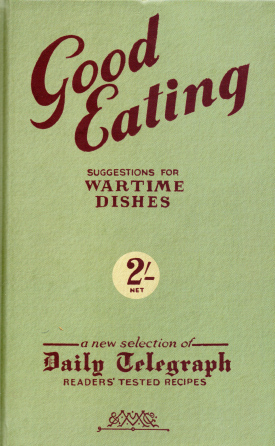

It would be difficult to argue otherwise when confronted with Terry’s “nauseating fish spread” of packing oil and oatmeal; “the repellent recipe for Winter Breakfast Spread” from the Daily Telegraph, leftover cooking fats “of different varieties” mixed with a crumbled stock cube (Good Eating 100); or the Ministry of Food’s own “savoury spread” for sandwiches made from a potato mashed with a paltry teaspoon of margarine. (Humble 98; Food Facts 121)

This was a ‘cuisine’ of expedience instead of coherence or taste; recipes were included in wartime cookbooks “because of their cheapness or their ingenious use of easily available ingredients.” Humble blames all this “improvisation” for a residual “coarsening of the national palate and a lingering suspicion of British food among those with culinary pretensions.” (Humble 93)

This was a ‘cuisine’ of expedience instead of coherence or taste; recipes were included in wartime cookbooks “because of their cheapness or their ingenious use of easily available ingredients.” Humble blames all this “improvisation” for a residual “coarsening of the national palate and a lingering suspicion of British food among those with culinary pretensions.” (Humble 93)

Once people got used to ersatz and processed products they kept relying on them: Cooks stick with the things they know. As a result, “wartime food products continued to be used for many years afterwards (Humble 104),” including custard powder, dried egg, canned fish, processed meat and instant coffee, this last a standby even of the revered Elizabeth David. Humble sounds convincing on the culinary legacy of wartime:

“Probably the furthest reaching, and most devastating, effect of the war on the standards of British cooking was in its encouragement of an increased reliance on…. more and more ways of preserving, dehydrating, packaging and generally denaturing food…. It was not so much the shortages of the Kitchen Front as its successes that were to haunt the future.” (Humble 104)

Sometimes, however, wartime recipes that strike us as bizarre served a cultural rather than gustatory purpose. These were a means of keeping faith with the past and hope for the future. If mock duck or fish tasted nothing like the unobtainable real thing, it could look like it and offer a symbol of normality. Thus, “large hollow cardboard ‘cakes’ were produced, decorated in what looked like magnificent royal icing.” It mattered not that the ‘cake’ and icing were inedible. They held a humble little fruitcake within and “appear resplendent in many a photograph of a wartime wedding.” (Humble 96)

6. Uses for the past: Outliers.

Some authors refused to join the patriotic Kitchen Front and espoused a radical rethink of making do, but their wartime impact in terms of what anybody did--or could--cook was negligible. Two of them emulated those floozies from France to extol its foodways instead of the weird new world of the Kitchen Front.

Constance Spry, who would achieve postwar prominence with the Coronation Chicken she created to celebrate the elevation of Elizabeth II and the subsequent publication of her Constance Spry Cookery Book, advocated hoarding ingredients for luxuriant creations. Her Come into the Garden, Cook from 1942 recommends piling weeks’ worth of egg and shortening rations into a single rich cake. She refuses “to paint a dim picture, to accentuate difficulties, to concentrate on leftovers and the best use of roots.” (Spry 1)

All of this, however, assumes that the reader has got a substantial garden and has not got a hungry family reliant overwhelmingly on the ration. It overlooks both the mechanics of rationing--points expired on a weekly basis--and the fact that most people lacked refrigeration to prevent eggs going rotten and fats turning rancid. It also disregards a significant component of the Kitchen Front campaign, promoting the notion that ‘we all are in this together.’ People obsessed with “what was not to be had and how so-and-so had had it” are less likely to notice the scrimping and hoarding necessary to create the special treat than the conspicuous consumption of it.

Sheila Kaye-Smith took a different approach. Instead of the Big Splurge she advocated the adoption of French and American cuisine during wartime, “the French because its methods conserve vitamins, and the American because it is economical with time and fuel, all goals that the ministry of food would applaud.” (Humble 103) Humble considers the recipes from Kaye-Smith, and Spry as well, more successful than the rest of the wartime run, but concedes that “they speak from a privileged position, and speak to others like themselves (Humble 103),” with the corrosive implications that the perspective entails. In any event it is difficult to imagine how any wartime cook could obtain access to the ingredients (roast sirloin, slices of ham, “waffles dripping with golden syrup”) that Kaye-Smith espouses without lavish resort to the black market. (Fugue 108-09)

Neither Spry nor Kaye-Smith actually did much to help the harried wartime housewife cope with the stresses of scarcity--except by offering a fantasy outlet that prefigures the work of David that began appearing with Mediterranean Food in 1950. Kaye-Smith in particular offers her reader extended meditations on the culture of eating rather than an emphasis on recipes alone.

7. Uses for the past: Simplicity itself.

With thorough research, or plain careful reading, it is possible to cull some workable, even appealing recipes from the mass of mockery and substitution. Once again, simplicity has become all the rage for busy cooks, and its principles share something with austerity. After all, wartime recipes were designed to save time as well as stretch rations, because housewives in their thousands joined the wartime labor force and consequently had little time to cook. Now that women work in the same numbers as men, we have cookbooks devoted to ‘five ingredient’ and ‘five minute’ dishes along with ‘The Minimalist’ and all manner of recipes ‘made easy.’ To tap our own busy but frugal recession market, the publisher’s blurb on the 2009 facsimile of Food Facts for the Kitchen Front from 1941 claims that it “is a fascinating, practical and very timely guide for the twenty-first century,” a time “when healthy home cooking matters more than cordon bleu.”

Food Facts intersperses a number of solid recipes with its foodbombs. Its barley broth (include a leek “if you have it”) is in reality a good rendition of the classic Scots broth; its summer pudding exactly what it purports to be, one of the great dessert courses from any cuisine, a pudding, as our Rural Correspondent says, made from ‘nothing,’ that is, from leftover bread and seasonal fruit. The white sauce contingent includes traditional, and excellent, anchovy, brain, caper, celery, mushroom, mustard and parsley variations, but please skip the version made “quickly, without fat.” (Food Facts 115; emphasis in original)

8. Over the airwaves.

8. Over the airwaves.

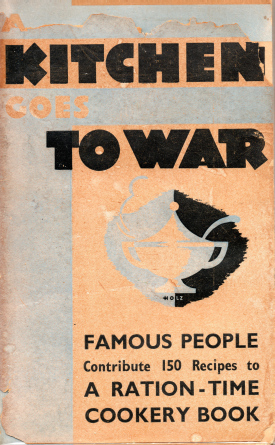

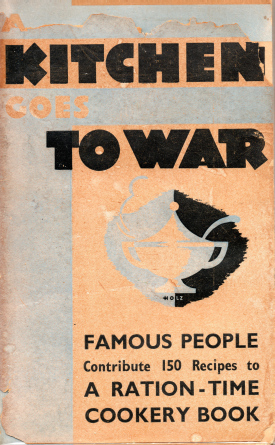

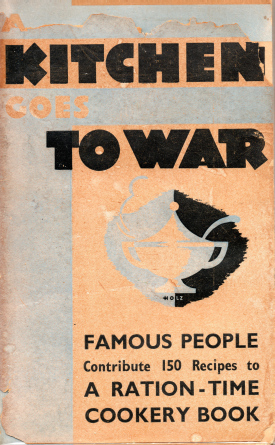

Kitchen Front Recipes by Ambrose Heath, and A Kitchen Goes to War, with recipes contributed by 150 famous or powerful people, are better books than the Ministry’s Food Facts. Heath, who has been called “one of the greatest cookery writers you.ve never heard of” (Begg), broadcast a series of early morning lectures about wartime cookery over the BBC for the Ministry of Food. Kitchen Front Recipes is a small selection of them. His approach to the exigencies of wartime cooking is precisely the approach of the Ministry, rendered with a surer touch and greater flair. Although he dutifully toes the doctrinal line (“really, there’s no end to the different sorts of potato cake that you can think of”), Heath is no culinary Spartan. Instead of treating food as a source of worry, he hopes to help his listeners, and latterly readers, to find some pleasure in hard times:

“After all, as a friend of mine said rather wistfully the other day, there aren’t a great many things to enjoy when there’s a war on, and we might as well enjoy our food. I do agree. If you enjoy your meals, I’m quite certain you’re getting far more benefit out of them than if you just sat down and… ate them. I’m sure that the difference between a human being and an animal is that the human being eats and the animal feeds: and if it hasn’t been said, it’s time somebody said it.” (Heath 13-14)

And yet reality intrudes, in the now predictable form of mock horrors, but also in a humanely constructive way. Heath concedes that “I don’t mean by this that people should eat food that takes a long time to prepare, because that would be idiotic nowadays” and offers recipes that, for example, require only “scraps of meat.” (Heath 14, 51-52) Like the Ministry and other wartime compilers of wartime recipes, he also recognizes that scarcity is constant so that flexibility is paramount. So add cheese to cabbage soup “if you can” and spread your hamburger “with a little margarine if you can spare it.” (Heath 31-32, 35)

His Sussex Blanket, a rolled suet pudding filled with sausage; bacon, liver and onion; or minced ham and seasoned with parsley and mace similar to britishfoodinamerica’s own bacon and onion pudding, is both hearty and appealing. Heath urges his audience to try the beet greens (“beetroot leaves”) beloved in the American south (a selling point he uncharacteristically omits), makes a mean meat loaf, stumbles into red flannel hash (the New England classic) and includes a thoroughly modern recipe for tomato and onion pie (without pastry).

Kitchen Front Recipes also subverts the conventional wisdom, espoused by Elizabeth David and repeated by journalists regurgitating her self-promotional assertion for decades, that olive oil was unused by English cooks until she ‘discovered’ it for them after the war. It is the foundation of Heath’s tomato sauce which, incidentally, is, as he says, “simplicity itself” and both authentic and quite good. (Heath 53)

Heath is a deft spokesman. When he engages in pure propaganda for the Ministry he is less cackhanded than the Ministry itself, so that when he suggests pooling ration tickets with friends to cook and dine together, it sounds like fun instead of drudgery.

9. Advice from the great and the good.

A Kitchen Goes to War, whose contributors include a ‘Mr. Flotsam’ and a ‘Mr. Jetsam,’ refuses to take itself or anyone else too seriously. It is both lighthearted and light fingered. Eva Turner “sends a cake that has had adventures.” It “was sent to the Front, traveled round France, chasing the owner, missed him and came back.” (Goes to War 1) Continuing the theme of mobility, a runner bean and bacon salad “[m]akes bacon go a long way.” (Goes to War 104)

Not to be eclipsed, Viscountess Hambleden offers the more sedentary Siege Cake and Dame Margaret Lloyd-George GBE stays at home and “supports home agriculture with Oatcakes.” (Goes to War 7) Agatha Christie “appropriately supplies a mystery recipe” and Jack Hobbs describes a galantine of chicken, if only because you “wouldn’t expect a duck from Jack.” (Goes to War 28, 40) (See Editor’s note following this essay)

Some of the recipes are pretty good, including an unconventional kedgeree of (unrationed) kidney and an inventive salad of shrimp and (also unrationed) sweetbreads.

Then again, Mrs. Josiah Wedgewood cannot really cook, so her “Tasty Emergency Snack” sends a roll topped with canned pilchards under the grill (that is, broiler) and Sir Kenneth Clark, director of the National Gallery, sends “a work of art” that turns out to be a ham sandwich. Best of all, the Punch columnist “Fougasse” has created the apotheosis of mockery, a Danish Frikadeller that, “when complete, is indistinguishable from chicken (or caviare or pate de foie gras or crepes suzette, or anything you specially fancy.” (Goes to War 38)

An omelette ‘Arnold Bennet’ arrives surreptitiously out of the Savoy kitchens without attribution and a traditional English recipe for skate is lifted straight from Mrs. Arthur Webb’s War-Time Cookery disguised as “Raie au Beurre Noir (Or, if necessary in wartime, Margarine Noir!).” (Goes to War 32)

War-Time Cookery had appeared in 1939 and, like the biplane fighter, was quickly proven obsolete in the conditions of war. At the time of publication, coal and other fuels already were rationed but food was not, so some of its recipes are (relatively) extravagant with ingredients that would turn out difficult to find. War-Time Cookery also strikes what would become a dissonant note in urging people to overcome prejudice toward tinned goods, which became scarce and coveted, and accept “Friendly Foods in Cans.” (War-Time Cookery 3)

It is a curious book with a beautiful cover.

A recipe for spiced liver includes no spice; “[c]orned beef turned out of the tin can be treated as a miniature joint” notwithstanding its diminutive size and absence of bone; and a ‘recipe’ for sheep’s head broth lists no ingredients and offers no instruction.

Good, traditional recipes, however, also appear, even if they would prove difficult to assemble from rations. The Mariner’s Casserole, a variation on Sea Pie, is flexible enough to utilize “[t]he elderly hen or duck, partridges or pheasants” and forcemeat balls along with the specified beef and pork; the Webb hot pot is true to Lancashire.

Our versions of Ambrose Heath’s recipes for tomato sauce, Sussex Blanket and some of his ‘Other Puddings’ that may include “finely chopped onion” but only “(if you can)” appear in the practical. Readers also will find there recipes for a bacon and mushroom pudding and pie that, like a certain salad, make bacon go a long way. An artistic ham sandwich and unconventional kedgeree also take bows along with Mrs. Webb’s “Lancashire Hot-Pot.”

10. On to the promised land.

In a good study of immigrant foodways in twentieth century Britain, Panikos Panayi notes that British recipes predominated in the publications produced by the Ministry of Food. He goes on to claim, however, that “the Ministry did not have any overt aim to develop a native cuisine.” (Panayi 14-16) We hope that the contours of this essay convince readers that such was not the case, both because the Ministry saw no need to ‘develop’ a complex weave of traditional foodways that already existed, and because the Ministry did indeed attempt to modify them, in some ways radically, in its quest for at least imperfect autarky during wartime.

If, however, the war alone cannot explain the decline in the competence of British cooks that persisted into the 1960s, it must have accelerated the declension. All those ersatz and processed products introduced as a means to increase the odds of national survival inadvertently amounted to convenience foods that precipitated the erosion of kitchen skills. And yet, despite the ravages of wartime expediency, and worst efforts of Elizabeth David and other postwar exponents of continental cuisines, the folk memory of a British cuisine never did quite die. Those risible mock dishes and substitute foods may not have been so bad after all, not in a certain respect. Perhaps, in the contemporary resuscitation of the British culinary tradition, we are witnessing their good works as keepers of the flame.

Editor’s note for American readers: Jack Hobbs was the greatest opening batsman in the history of English cricket. He would not duck a ball.

Sources:

anon. [Daily Telegraph ‘Home Cook’], Good Eating: Suggestions for Wartime Dishes (London 194?, 2006 facsimile)

anon. [United Kingdom Ministry of Food], Food Facts for the Kitchen Front (London 1941, 2009 facsimile)

Peter Begg, “A Man for All Seasons,” Jamie Magazine (August-September 2009)

Lizzie Collingham, The Taste of War (London 2011)

Jane Fearnley-Whittingstall, The Ministry of Food (London 2010)

The great and the good (150 contributors), A Kitchen Goes to War (London 1940)

Ambrose Heath, Kitchen Front Recipes (London 1941)

Nicola Humble, Culinary Pleasures: Cookbooks and the Transformation of English Food (London 2005)

Rose Macaulay, Life Among the English (London 1942, 1996)

Panikos Panayi, Spicing Up Britain: The Multicultural History of British Food (London 2008)

Josephine Terry, Food for the Future (London 1941)

Food Without Fuss (London 1944)

Mrs. Arthur Webb, War-Time Cookery (Letchworth, England 1939)

Alan Wilt, Food for War: Agriculture and Rearmament in Britain Before the Second World War (Oxford 2001)

During the Second World War, all governments worried that food shortages would cause social unrest and strategic catastrophe. Strategic setbacks related to food supply and starvation itself would in fact plague a number of combatants and their victims both during and after the war.

Britain faced a particular challenge to feed its population for several reasons. It could, or would, not control hungry masses by coercion like the Soviet Union or Axis countries, and unlike them did not loot its neighbors. Unlike the United States, Britain lacked a vastness of arable land to produce reliable agricultural surpluses.

Instead, in a classic case of comparative advantage, industrial Britain had been a net importer of food for decades before the onset of war. This wartime disadvantage was compounded because so much of its food arrived by sea. In 1939, Britain imported more than sixty percent of its foodstuffs, a number that understates the nation’s reliance on the sea lanes because farmers also relied on imports of winter feed for their animals. (Ministry 20)

1. In the country.

To meet the problem on the home front, Britain nationalized control and production of agriculture.  Nonessentials like flowers were plowed under, wetlands drained and scrubland cleared. The Ministry of Food set quotas for crops and livestock, imposed price controls and, in 1940, food rationing. Grains feed more people per acre than dairy herds, dairy feeds more people than meat; wartime production of grains therefore soared at the expense of livestock, and fresh milk became less plentiful.

Nonessentials like flowers were plowed under, wetlands drained and scrubland cleared. The Ministry of Food set quotas for crops and livestock, imposed price controls and, in 1940, food rationing. Grains feed more people per acre than dairy herds, dairy feeds more people than meat; wartime production of grains therefore soared at the expense of livestock, and fresh milk became less plentiful.

By 1944, Britain had added 6.5 million acres of farmland; by 1945, the amount of land under cultivation had increased eighty percent from prewar levels and imports of food cut by half. The production of oats increased by fifty eight percent; the production of barley, potatoes and wheat each doubled. (Ministry 20)

According to Lizzie Collingham, this increase was due more to long hours of sheer labor than horticultural or technological innovation, and she has an argument. (Collingham 89-90) The native agricultural workforce appears to have increased by only about a sixth between 1939 and 1944, when 117,000 recruits to the Women’s Land Army replaced 98,000 farm workers lost to conscription, but seasonal labor, mostly students and faculty during summer time, and over 50,000 prisoners of war also eventually worked in British fields. (Collingham 95; Ministry 20) Despite Collingham’s doubts, however, technology may have helped too; for example, the number of tractors employed in British agriculture increased from some 56,000 on the eve of war to 203,000 in 1946. (Wilt 226)

This increase in self-sufficiency had the side effect of decreasing the variety of fruit and vegetables available in Britain. Its climate is comparatively cold, so that while root vegetables may thrive and orchards may yield, the growing season for ‘luxury’ items like asparagus, tomatoes or fruit other than apples is short and sometimes precarious. The bumper crops harvested on a wartime footing bred a numbing monotony at the table.

Collingham, a rather strident revisionist, argues that this “restructuring of agriculture was a modest success,” nothing more. (Collingham 96) By any statistical measure, the transformation of the British landscape was in fact a considerable achievement, but she is right that imports, predominantly of processed proteins, still accounted for a little more than half the calories (as opposed to bulk) consumed in wartime. Even without battle losses, shipping space remained scarce for most of the war, so that “condensing food was the key to keeping Britain fed.” (Collingham 101)

2. On board ship.

The volume of meat products was reduced by “de-boning, telescoping and canning;” dried egg powder displaced twenty percent of the volume required by the real thing and boasted an infinite shelf life along with its terrible taste. “A variety of other unspeakable powders and pastes was manufactured” as well. (Collingham 100) Many of the processed meat products (some dried, others frozen) were little better, and the processed cheese substitute from a tube was nearly inedible, “a soapy wartime product.” (Garfield quoted in Collingham 100) Despite all this, however, it is a reliable trope to observe that the British people, and in particular the poorer among them, were better fed in terms of nutrition during the war that at any time since the onset of the urban industrial revolution. As Collingham notes, however, “if the British did not sacrifice the energy content of their food they did sacrifice taste.” (Collingham 100-01) Wartime food, with few exceptions, was no fun.

The volume of meat products was reduced by “de-boning, telescoping and canning;” dried egg powder displaced twenty percent of the volume required by the real thing and boasted an infinite shelf life along with its terrible taste. “A variety of other unspeakable powders and pastes was manufactured” as well. (Collingham 100) Many of the processed meat products (some dried, others frozen) were little better, and the processed cheese substitute from a tube was nearly inedible, “a soapy wartime product.” (Garfield quoted in Collingham 100) Despite all this, however, it is a reliable trope to observe that the British people, and in particular the poorer among them, were better fed in terms of nutrition during the war that at any time since the onset of the urban industrial revolution. As Collingham notes, however, “if the British did not sacrifice the energy content of their food they did sacrifice taste.” (Collingham 100-01) Wartime food, with few exceptions, was no fun.

3. At the stove.

If expedience replaced flavor in much of wartime food, unpredictable supply added another level of dislocation. Even during the blitz, conversation on the home front therefore

“tended to turn on.... food: what was permitted, what was to be had, what was not permitted and where this was to be had and at what cost, what was not to be had and how so-and-so had had it. When bombs were not descending, or ruins being searched for household goods before the demolition men could get at them, food talk often beat bomb talk.” (Macaulay 93)

The Ministry of Food, especially in the person of Lord Woolton, whom we will appreciate in the lyrical, was neither unaware nor unsympathetic, and met the discomfiture head-on through a peculiar British combination of propaganda and homely hints. These appeared through a number of media including the famous and beautiful posters promoting healthy and frugal eating, radio broadcasts, ‘Dig for Victory’ leaflets and any number of wartime cookbooks produced “in complete conformity with the authorized economy standards.

Much of this effort entailed promotion of the war effort through shared exertion and sacrifice, but some of it attempted to meliorate the hardship. The cookbooks served both functions. They all measure less than eight inches high by five wide and seldom exceed 130 pages; their paper is thin and has become brittle seventy years on. At first it may seem dissonant to divert scarce resources to print cookbooks during a national emergency, but the government encouraged publication of the little volumes, and printed some of them itself, in an effort to help the public cope not only with unfamiliar and frequently unpalatable products, but also with the sheer dullness of wartime sustenance. Fats of all kind, for example, were scarce, and plain boiled food gets tedious fast.

4. From the books.

Many wartime cookbooks demonstrate that a certain level of imagination is a dangerous thing. Scattered throughout them you will find mock chops, duck, fish pie, flan, game, goose, whitebait, marzipan and other ersatz substances, sculpted from potatoes, artichokes, carrot, soy, even oversized zucchini and other vegetables. They are best left undescribed and, like the ‘Wild Turkey Surprise’ made from dynamite that Bugs feeds the Tasmanian Devil to blow him up, undisturbed. If, however, it is easy to mock all this wartime mockery, not much has changed, at least in some circles. Vegetarians trying to slake their bloodlust without guilt can find multiple brands of fake burgers, fake sausage, even fake bacon and “tofurkey,” frequently fashioned from soybeans. These awful substitutes would have delighted the Ministry of Food.

One of its publications, Food Facts for the Kitchen Front, opens with a blast of unabashed exhortatory propaganda:

“In these days, when we are all beginning to concern ourselves with essentials and to discard the things that do not matter, it is necessary to remember these two facts:

1. What we can get is good for us.

2. A great deal of what we cannot get is quite unimportant.” (Food Facts 6; emphasis in original)

If, however, the Ministry of Food teeters on bombast, and betrays a pathological obsession with potatoes, it manages not to slip into the precipice. Its patriotism is not unbound and the Ministry cannot resist a wry joke. Thus the admission of received culinary Anglophobia: “It was once said that English cooking demanded a Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Vegetables.” (Food Facts 10) In the new dawn of healthy wartime eating, the SPVA would become superfluous because an innovative cuisine could sweep the archipelago. This novelty, however, often was more apparent than real, for as Nicola Humble has noted, many traditional dishes, both British and foreign, were simply cast from their historical tether and given new names.

If, however, the Ministry of Food teeters on bombast, and betrays a pathological obsession with potatoes, it manages not to slip into the precipice. Its patriotism is not unbound and the Ministry cannot resist a wry joke. Thus the admission of received culinary Anglophobia: “It was once said that English cooking demanded a Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Vegetables.” (Food Facts 10) In the new dawn of healthy wartime eating, the SPVA would become superfluous because an innovative cuisine could sweep the archipelago. This novelty, however, often was more apparent than real, for as Nicola Humble has noted, many traditional dishes, both British and foreign, were simply cast from their historical tether and given new names.

Food Facts imagines that a soup of cabbage, potato, milk and water--essentially colcannon thinned for a time of scarcity--may masquerade as “Creole Soup.” Similar wan attempts to render the humdrum exotic pop up throughout our genre, not least in the titillating work of Josephine Terry, who sounds like she bounces about with a coat hanger upside down in her mouth. In Food Without Fuss she includes a “New Orleans Bake” made from parsnips and beef dripping, which only could appear in the Crescent City of an alternative universe. She is, however, like the object of Ignatius’ desire in A Confederacy of Dunces, one saucy minx and, like Myrna herself, bookish.

Terry also is the Total Woman of wartime.

“To our delight we housewives of to-day find ourselves in a somewhat exalted position. Each time we serve a meal we stand in the limelight, facing an audience of men and children--with large appetites and small rations.

“We know their health and happiness depend on us, up to a point. But what a point! Everyone has become wise about the merits of a good meal, and never before have we received such wholehearted appreciation.

“We like it.” (Fuss 11)

When not busy channeling Hank Williams and Lord Copper’s stooge, would this exhibitionist greet that man wearing ought but apron, martini in hand? Perhaps not when the kids were about.

Elsewhere Terry entreats the sisterhood to persevere. In her version of ‘Lie back and think of England’, entitled “Your Bit--Well Done,” she reminds them that

“We all know that some of our good fortune has come to us through something we disliked very much at the time, through happenings, unpleasant or tragic, which proved later on to be good for us.

The present food shortage may well be such a happening. Hard to endure at times, it makes us aware of many new tastes and provides thrills which otherwise we should have missed.” (Future 7)

Terry applauds experimentation, and finds it strange “that a people as fond of flowers…. might have never paid attention to edible plants which is due to them” but for the inhibitions released by the pressure of war. (Future 40)

“I’ve got an edible plant for you.” or “Would you like to nibble my knockies?”

There is a paean to The Cosy Box, “one of those humble things in life which prove to be invaluable.” Regular use of this “nest” empowers its owner. “The Cosy Box enables us to leave the house cheerfully for a long stroll along the river, for an excursion, in pursuit of an invitation….” (Future 94-95) It also allows its owner to simmer stews with very little energy, like an improvised precursor of the crock pot.

Terry is not snobbish about her companions in the kitchen; even homely soya takes her breath away. “This little word, brief and musical, heads one of the most sensational stories of the world’s hidden treasures.” (Fuss 143)

As melancholy may follow climax, however, these little books betray an inadvertent poignancy. Terry may enjoy nibbling velvety buds, but is practical enough to recognize that sometimes a girl has no choice but to look for help from unattractive sources. Her recipe for ‘Gold Diggers’ Soup made from flour and dried egg does the nutritional trick but packs no thrill. (Fuss 143)

Sometimes she relies on fantasy to get the job done. One chapter of Food Without Fuss is devoted to “Make-Believe Dishes,” which, despite expectations, do not include the mock items, although there is a recipe for “artificial gravy.”

The Ministry of Food is frank enough to scatter recipes with little admissions of failure to satisfy its women. The instructions for a ‘Dutch casserole’ (in terms of authenticity see “Creole Soup”) call for “[a] few dried plums, if available;” others, for boiled vegetables (the ‘Autumn Platter’) call for a cover of grated cheese, “if you have it” before specifying “about 2 dessertspoons or what can be spared” and a recipe for soup suggests the addition of “a little milk when it can be spared.”(Facts 40, 41, 102)) Others follow listed ingredients with an apologetic “if possible.”

The otherwise optimistic Terry also uses “if possible” as a trailer and recognizes elsewhere that some desires may be unfulfilled. In a recipe for ‘Delicate cups’ she suggests anointing the delicate flesh with gelatin “and, if you can get it, a few drops of wine or brandy.” Her ‘Goulash Knockies’ benefit from a squirt of “meat extract” and “if you can get it, any kind of tomato sauce or juice or puree.” (Future 14, 17)

Ambrose Heath also makes allowances for scarcity in his wartime recipes. They variously recommend the addition of cheese, milk or onions, but only “if you can.” (See, e.g. Kitchen Front 30-31, 34, 35, 51-52)

5. An unfortunate future.

The scarcity of former staples and reliance on processed protein products encouraged authors to create ghastly recipes and cooks to acquire unfortunate habits. According to Nicola Humble, the “combination of limited ingredients and a licence to experiment meant that the cookbooks of the Second World War contained some of the most unpleasant food of the last 150 years.” (Humble 101)

It would be difficult to argue otherwise when confronted with Terry’s “nauseating fish spread” of packing oil and oatmeal; “the repellent recipe for Winter Breakfast Spread” from the Daily Telegraph, leftover cooking fats “of different varieties” mixed with a crumbled stock cube (Good Eating 100); or the Ministry of Food’s own “savoury spread” for sandwiches made from a potato mashed with a paltry teaspoon of margarine. (Humble 98; Food Facts 121)

This was a ‘cuisine’ of expedience instead of coherence or taste; recipes were included in wartime cookbooks “because of their cheapness or their ingenious use of easily available ingredients.” Humble blames all this “improvisation” for a residual “coarsening of the national palate and a lingering suspicion of British food among those with culinary pretensions.” (Humble 93)

This was a ‘cuisine’ of expedience instead of coherence or taste; recipes were included in wartime cookbooks “because of their cheapness or their ingenious use of easily available ingredients.” Humble blames all this “improvisation” for a residual “coarsening of the national palate and a lingering suspicion of British food among those with culinary pretensions.” (Humble 93)

Once people got used to ersatz and processed products they kept relying on them: Cooks stick with the things they know. As a result, “wartime food products continued to be used for many years afterwards (Humble 104),” including custard powder, dried egg, canned fish, processed meat and instant coffee, this last a standby even of the revered Elizabeth David. Humble sounds convincing on the culinary legacy of wartime:

“Probably the furthest reaching, and most devastating, effect of the war on the standards of British cooking was in its encouragement of an increased reliance on…. more and more ways of preserving, dehydrating, packaging and generally denaturing food…. It was not so much the shortages of the Kitchen Front as its successes that were to haunt the future.” (Humble 104)

Sometimes, however, wartime recipes that strike us as bizarre served a cultural rather than gustatory purpose. These were a means of keeping faith with the past and hope for the future. If mock duck or fish tasted nothing like the unobtainable real thing, it could look like it and offer a symbol of normality. Thus, “large hollow cardboard ‘cakes’ were produced, decorated in what looked like magnificent royal icing.” It mattered not that the ‘cake’ and icing were inedible. They held a humble little fruitcake within and “appear resplendent in many a photograph of a wartime wedding.” (Humble 96)

6. Uses for the past: Outliers.

Some authors refused to join the patriotic Kitchen Front and espoused a radical rethink of making do, but their wartime impact in terms of what anybody did--or could--cook was negligible. Two of them emulated those floozies from France to extol its foodways instead of the weird new world of the Kitchen Front.

Constance Spry, who would achieve postwar prominence with the Coronation Chicken she created to celebrate the elevation of Elizabeth II and the subsequent publication of her Constance Spry Cookery Book, advocated hoarding ingredients for luxuriant creations. Her Come into the Garden, Cook from 1942 recommends piling weeks’ worth of egg and shortening rations into a single rich cake. She refuses “to paint a dim picture, to accentuate difficulties, to concentrate on leftovers and the best use of roots.” (Spry 1)

All of this, however, assumes that the reader has got a substantial garden and has not got a hungry family reliant overwhelmingly on the ration. It overlooks both the mechanics of rationing--points expired on a weekly basis--and the fact that most people lacked refrigeration to prevent eggs going rotten and fats turning rancid. It also disregards a significant component of the Kitchen Front campaign, promoting the notion that ‘we all are in this together.’ People obsessed with “what was not to be had and how so-and-so had had it” are less likely to notice the scrimping and hoarding necessary to create the special treat than the conspicuous consumption of it.

Sheila Kaye-Smith took a different approach. Instead of the Big Splurge she advocated the adoption of French and American cuisine during wartime, “the French because its methods conserve vitamins, and the American because it is economical with time and fuel, all goals that the ministry of food would applaud.” (Humble 103) Humble considers the recipes from Kaye-Smith, and Spry as well, more successful than the rest of the wartime run, but concedes that “they speak from a privileged position, and speak to others like themselves (Humble 103),” with the corrosive implications that the perspective entails. In any event it is difficult to imagine how any wartime cook could obtain access to the ingredients (roast sirloin, slices of ham, “waffles dripping with golden syrup”) that Kaye-Smith espouses without lavish resort to the black market. (Fugue 108-09)

Neither Spry nor Kaye-Smith actually did much to help the harried wartime housewife cope with the stresses of scarcity--except by offering a fantasy outlet that prefigures the work of David that began appearing with Mediterranean Food in 1950. Kaye-Smith in particular offers her reader extended meditations on the culture of eating rather than an emphasis on recipes alone.

7. Uses for the past: Simplicity itself.

With thorough research, or plain careful reading, it is possible to cull some workable, even appealing recipes from the mass of mockery and substitution. Once again, simplicity has become all the rage for busy cooks, and its principles share something with austerity. After all, wartime recipes were designed to save time as well as stretch rations, because housewives in their thousands joined the wartime labor force and consequently had little time to cook. Now that women work in the same numbers as men, we have cookbooks devoted to ‘five ingredient’ and ‘five minute’ dishes along with ‘The Minimalist’ and all manner of recipes ‘made easy.’ To tap our own busy but frugal recession market, the publisher’s blurb on the 2009 facsimile of Food Facts for the Kitchen Front from 1941 claims that it “is a fascinating, practical and very timely guide for the twenty-first century,” a time “when healthy home cooking matters more than cordon bleu.”

Food Facts intersperses a number of solid recipes with its foodbombs. Its barley broth (include a leek “if you have it”) is in reality a good rendition of the classic Scots broth; its summer pudding exactly what it purports to be, one of the great dessert courses from any cuisine, a pudding, as our Rural Correspondent says, made from ‘nothing,’ that is, from leftover bread and seasonal fruit. The white sauce contingent includes traditional, and excellent, anchovy, brain, caper, celery, mushroom, mustard and parsley variations, but please skip the version made “quickly, without fat.” (Food Facts 115; emphasis in original)

8. Over the airwaves.

8. Over the airwaves.

Kitchen Front Recipes by Ambrose Heath, and A Kitchen Goes to War, with recipes contributed by 150 famous or powerful people, are better books than the Ministry’s Food Facts. Heath, who has been called “one of the greatest cookery writers you.ve never heard of” (Begg), broadcast a series of early morning lectures about wartime cookery over the BBC for the Ministry of Food. Kitchen Front Recipes is a small selection of them. His approach to the exigencies of wartime cooking is precisely the approach of the Ministry, rendered with a surer touch and greater flair. Although he dutifully toes the doctrinal line (“really, there’s no end to the different sorts of potato cake that you can think of”), Heath is no culinary Spartan. Instead of treating food as a source of worry, he hopes to help his listeners, and latterly readers, to find some pleasure in hard times:

“After all, as a friend of mine said rather wistfully the other day, there aren’t a great many things to enjoy when there’s a war on, and we might as well enjoy our food. I do agree. If you enjoy your meals, I’m quite certain you’re getting far more benefit out of them than if you just sat down and… ate them. I’m sure that the difference between a human being and an animal is that the human being eats and the animal feeds: and if it hasn’t been said, it’s time somebody said it.” (Heath 13-14)

And yet reality intrudes, in the now predictable form of mock horrors, but also in a humanely constructive way. Heath concedes that “I don’t mean by this that people should eat food that takes a long time to prepare, because that would be idiotic nowadays” and offers recipes that, for example, require only “scraps of meat.” (Heath 14, 51-52) Like the Ministry and other wartime compilers of wartime recipes, he also recognizes that scarcity is constant so that flexibility is paramount. So add cheese to cabbage soup “if you can” and spread your hamburger “with a little margarine if you can spare it.” (Heath 31-32, 35)

His Sussex Blanket, a rolled suet pudding filled with sausage; bacon, liver and onion; or minced ham and seasoned with parsley and mace similar to britishfoodinamerica’s own bacon and onion pudding, is both hearty and appealing. Heath urges his audience to try the beet greens (“beetroot leaves”) beloved in the American south (a selling point he uncharacteristically omits), makes a mean meat loaf, stumbles into red flannel hash (the New England classic) and includes a thoroughly modern recipe for tomato and onion pie (without pastry).

Kitchen Front Recipes also subverts the conventional wisdom, espoused by Elizabeth David and repeated by journalists regurgitating her self-promotional assertion for decades, that olive oil was unused by English cooks until she ‘discovered’ it for them after the war. It is the foundation of Heath’s tomato sauce which, incidentally, is, as he says, “simplicity itself” and both authentic and quite good. (Heath 53)

Heath is a deft spokesman. When he engages in pure propaganda for the Ministry he is less cackhanded than the Ministry itself, so that when he suggests pooling ration tickets with friends to cook and dine together, it sounds like fun instead of drudgery.

9. Advice from the great and the good.

A Kitchen Goes to War, whose contributors include a ‘Mr. Flotsam’ and a ‘Mr. Jetsam,’ refuses to take itself or anyone else too seriously. It is both lighthearted and light fingered. Eva Turner “sends a cake that has had adventures.” It “was sent to the Front, traveled round France, chasing the owner, missed him and came back.” (Goes to War 1) Continuing the theme of mobility, a runner bean and bacon salad “[m]akes bacon go a long way.” (Goes to War 104)

Not to be eclipsed, Viscountess Hambleden offers the more sedentary Siege Cake and Dame Margaret Lloyd-George GBE stays at home and “supports home agriculture with Oatcakes.” (Goes to War 7) Agatha Christie “appropriately supplies a mystery recipe” and Jack Hobbs describes a galantine of chicken, if only because you “wouldn’t expect a duck from Jack.” (Goes to War 28, 40) (See Editor’s note following this essay)

Some of the recipes are pretty good, including an unconventional kedgeree of (unrationed) kidney and an inventive salad of shrimp and (also unrationed) sweetbreads.

Then again, Mrs. Josiah Wedgewood cannot really cook, so her “Tasty Emergency Snack” sends a roll topped with canned pilchards under the grill (that is, broiler) and Sir Kenneth Clark, director of the National Gallery, sends “a work of art” that turns out to be a ham sandwich. Best of all, the Punch columnist “Fougasse” has created the apotheosis of mockery, a Danish Frikadeller that, “when complete, is indistinguishable from chicken (or caviare or pate de foie gras or crepes suzette, or anything you specially fancy.” (Goes to War 38)

An omelette ‘Arnold Bennet’ arrives surreptitiously out of the Savoy kitchens without attribution and a traditional English recipe for skate is lifted straight from Mrs. Arthur Webb’s War-Time Cookery disguised as “Raie au Beurre Noir (Or, if necessary in wartime, Margarine Noir!).” (Goes to War 32)

War-Time Cookery had appeared in 1939 and, like the biplane fighter, was quickly proven obsolete in the conditions of war. At the time of publication, coal and other fuels already were rationed but food was not, so some of its recipes are (relatively) extravagant with ingredients that would turn out difficult to find. War-Time Cookery also strikes what would become a dissonant note in urging people to overcome prejudice toward tinned goods, which became scarce and coveted, and accept “Friendly Foods in Cans.” (War-Time Cookery 3)

It is a curious book with a beautiful cover.

A recipe for spiced liver includes no spice; “[c]orned beef turned out of the tin can be treated as a miniature joint” notwithstanding its diminutive size and absence of bone; and a ‘recipe’ for sheep’s head broth lists no ingredients and offers no instruction.

Good, traditional recipes, however, also appear, even if they would prove difficult to assemble from rations. The Mariner’s Casserole, a variation on Sea Pie, is flexible enough to utilize “[t]he elderly hen or duck, partridges or pheasants” and forcemeat balls along with the specified beef and pork; the Webb hot pot is true to Lancashire.

Our versions of Ambrose Heath’s recipes for tomato sauce, Sussex Blanket and some of his ‘Other Puddings’ that may include “finely chopped onion” but only “(if you can)” appear in the practical. Readers also will find there recipes for a bacon and mushroom pudding and pie that, like a certain salad, make bacon go a long way. An artistic ham sandwich and unconventional kedgeree also take bows along with Mrs. Webb’s “Lancashire Hot-Pot.”

10. On to the promised land.

In a good study of immigrant foodways in twentieth century Britain, Panikos Panayi notes that British recipes predominated in the publications produced by the Ministry of Food. He goes on to claim, however, that “the Ministry did not have any overt aim to develop a native cuisine.” (Panayi 14-16) We hope that the contours of this essay convince readers that such was not the case, both because the Ministry saw no need to ‘develop’ a complex weave of traditional foodways that already existed, and because the Ministry did indeed attempt to modify them, in some ways radically, in its quest for at least imperfect autarky during wartime.

If, however, the war alone cannot explain the decline in the competence of British cooks that persisted into the 1960s, it must have accelerated the declension. All those ersatz and processed products introduced as a means to increase the odds of national survival inadvertently amounted to convenience foods that precipitated the erosion of kitchen skills. And yet, despite the ravages of wartime expediency, and worst efforts of Elizabeth David and other postwar exponents of continental cuisines, the folk memory of a British cuisine never did quite die. Those risible mock dishes and substitute foods may not have been so bad after all, not in a certain respect. Perhaps, in the contemporary resuscitation of the British culinary tradition, we are witnessing their good works as keepers of the flame.

Editor’s note for American readers: Jack Hobbs was the greatest opening batsman in the history of English cricket. He would not duck a ball.

Sources:

anon. [Daily Telegraph ‘Home Cook’], Good Eating: Suggestions for Wartime Dishes (London 194?, 2006 facsimile)

anon. [United Kingdom Ministry of Food], Food Facts for the Kitchen Front (London 1941, 2009 facsimile)

Peter Begg, “A Man for All Seasons,” Jamie Magazine (August-September 2009)

Lizzie Collingham, The Taste of War (London 2011)

Jane Fearnley-Whittingstall, The Ministry of Food (London 2010)

The great and the good (150 contributors), A Kitchen Goes to War (London 1940)

Ambrose Heath, Kitchen Front Recipes (London 1941)

Nicola Humble, Culinary Pleasures: Cookbooks and the Transformation of English Food (London 2005)

Rose Macaulay, Life Among the English (London 1942, 1996)

Panikos Panayi, Spicing Up Britain: The Multicultural History of British Food (London 2008)

Josephine Terry, Food for the Future (London 1941)

Food Without Fuss (London 1944)

Mrs. Arthur Webb, War-Time Cookery (Letchworth, England 1939)

Alan Wilt, Food for War: Agriculture and Rearmament in Britain Before the Second World War (Oxford 2001)

Nonessentials like flowers were plowed under, wetlands drained and scrubland cleared. The Ministry of Food set quotas for crops and livestock, imposed price controls and, in 1940, food rationing. Grains feed more people per acre than dairy herds, dairy feeds more people than meat; wartime production of grains therefore soared at the expense of livestock, and fresh milk became less plentiful.

Nonessentials like flowers were plowed under, wetlands drained and scrubland cleared. The Ministry of Food set quotas for crops and livestock, imposed price controls and, in 1940, food rationing. Grains feed more people per acre than dairy herds, dairy feeds more people than meat; wartime production of grains therefore soared at the expense of livestock, and fresh milk became less plentiful. The volume of meat products was reduced by “de-boning, telescoping and canning;” dried egg powder displaced twenty percent of the volume required by the real thing and boasted an infinite shelf life along with its terrible taste. “A variety of other unspeakable powders and pastes was manufactured” as well. (Collingham 100) Many of the processed meat products (some dried, others frozen) were little better, and the processed cheese substitute from a tube was nearly inedible, “a soapy wartime product.” (Garfield quoted in Collingham 100) Despite all this, however, it is a reliable trope to observe that the British people, and in particular the poorer among them, were better fed in terms of nutrition during the war that at any time since the onset of the urban industrial revolution. As Collingham notes, however, “if the British did not sacrifice the energy content of their food they did sacrifice taste.” (Collingham 100-01) Wartime food, with few exceptions, was no fun.

The volume of meat products was reduced by “de-boning, telescoping and canning;” dried egg powder displaced twenty percent of the volume required by the real thing and boasted an infinite shelf life along with its terrible taste. “A variety of other unspeakable powders and pastes was manufactured” as well. (Collingham 100) Many of the processed meat products (some dried, others frozen) were little better, and the processed cheese substitute from a tube was nearly inedible, “a soapy wartime product.” (Garfield quoted in Collingham 100) Despite all this, however, it is a reliable trope to observe that the British people, and in particular the poorer among them, were better fed in terms of nutrition during the war that at any time since the onset of the urban industrial revolution. As Collingham notes, however, “if the British did not sacrifice the energy content of their food they did sacrifice taste.” (Collingham 100-01) Wartime food, with few exceptions, was no fun.

If, however, the Ministry of Food teeters on bombast, and betrays a pathological obsession with potatoes, it manages not to slip into the precipice. Its patriotism is not unbound and the Ministry cannot resist a wry joke. Thus the admission of received culinary Anglophobia: “It was once said that English cooking demanded a Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Vegetables.” (Food Facts 10) In the new dawn of healthy wartime eating, the SPVA would become superfluous because an innovative cuisine could sweep the archipelago. This novelty, however, often was more apparent than real, for as Nicola Humble has noted, many traditional dishes, both British and foreign, were simply cast from their historical tether and given new names.

If, however, the Ministry of Food teeters on bombast, and betrays a pathological obsession with potatoes, it manages not to slip into the precipice. Its patriotism is not unbound and the Ministry cannot resist a wry joke. Thus the admission of received culinary Anglophobia: “It was once said that English cooking demanded a Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Vegetables.” (Food Facts 10) In the new dawn of healthy wartime eating, the SPVA would become superfluous because an innovative cuisine could sweep the archipelago. This novelty, however, often was more apparent than real, for as Nicola Humble has noted, many traditional dishes, both British and foreign, were simply cast from their historical tether and given new names.

This was a ‘cuisine’ of expedience instead of coherence or taste; recipes were included in wartime cookbooks “because of their cheapness or their ingenious use of easily available ingredients.” Humble blames all this “improvisation” for a residual “coarsening of the national palate and a lingering suspicion of British food among those with culinary pretensions.” (Humble 93)

This was a ‘cuisine’ of expedience instead of coherence or taste; recipes were included in wartime cookbooks “because of their cheapness or their ingenious use of easily available ingredients.” Humble blames all this “improvisation” for a residual “coarsening of the national palate and a lingering suspicion of British food among those with culinary pretensions.” (Humble 93) 8. Over the airwaves.

8. Over the airwaves.