The Financial Times & the Art of Eating, or Good Taste is No Fun.

At the last New Year the weekend edition of the Financial Times featured Edward Behr and his quarterly journal, the Art of Eating, as the subject of a lengthy article on the front page of the paper’s “Life & Arts” section. The article is excellent and portrays Behr and his journal--he does most of the writing--with sympathy and admiration.

Behr started the Art of Eating in 1986 and continues to run the operation from his rural redoubt in the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont (“no postal delivery at this address” according to the journal’s information banner). It is not clear why its title begins in lower case, but the nonstandard usage is typical of Behr’s quirks. The journal started as little more than a sheaf of papers; eventually it evolved into its current, more professional incarnation. The journal is bound, the artwork attractive and, as the FT notes, the layout is both austere and beautiful. Behr has integrity; he has kept true to his independent vision in refusing offers of advertising or expansion, and has ruled out a website; he likes the craft of words on paper, and we admire him for that.

Behr started the Art of Eating in 1986 and continues to run the operation from his rural redoubt in the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont (“no postal delivery at this address” according to the journal’s information banner). It is not clear why its title begins in lower case, but the nonstandard usage is typical of Behr’s quirks. The journal started as little more than a sheaf of papers; eventually it evolved into its current, more professional incarnation. The journal is bound, the artwork attractive and, as the FT notes, the layout is both austere and beautiful. Behr has integrity; he has kept true to his independent vision in refusing offers of advertising or expansion, and has ruled out a website; he likes the craft of words on paper, and we admire him for that.

The Art of Eating has garnered an enviable subscription list that includes Dan Barber, Belinda Chang (who describes the journal as “PhD level food writing”), Charlie Trotter and Alice Waters, among others. Each issue leads with a lengthy article that addresses a discrete subject in depth. This brew of praise from the FT, a reputation for good writing, high production values and the enthusiastic testimony of the magazine’s luminous acolytes intrigued us, and made us curious whether the Art of Eating had ever addressed British food. We found that it had: The lead article of number 61, from July 2002, is called “English Food.”

The first subtitle of the article is “And how good is English food?,” a promising start that does not, however, describe the contents of the first section. Instead it repeats the standard premise that English food is horrible, based upon an anecdote of Behr’s from the 1980s and writings from the 1930s by the Francophile Sir Francis Colchester-Wemyss and P. Morton Shand. Shand offers only the tiresome dogma that excellent meat and produce are brutalized in English kitchens. Subsequent sections of the article do, however, offer a more contemporary assessment.

.jpg) The article oscillates from the overly general (“Overall, there’s a strong liking for sugar” AoE 6) to the pointlessly detailed. Its tone is encapsulated in the coy section titles: “The raw materials,” “The fate of the raw materials,” “A possible explanation for why there isn’t more good cooking,” “Real Cornish saffron buns” (an obsession of Behr’s that hardly illuminates his larger subject), “Local beer,” and, portentously, “The meaning of Heston Blumenthal and the Fat Duck” follow “How good is English food?”

The article oscillates from the overly general (“Overall, there’s a strong liking for sugar” AoE 6) to the pointlessly detailed. Its tone is encapsulated in the coy section titles: “The raw materials,” “The fate of the raw materials,” “A possible explanation for why there isn’t more good cooking,” “Real Cornish saffron buns” (an obsession of Behr’s that hardly illuminates his larger subject), “Local beer,” and, portentously, “The meaning of Heston Blumenthal and the Fat Duck” follow “How good is English food?”

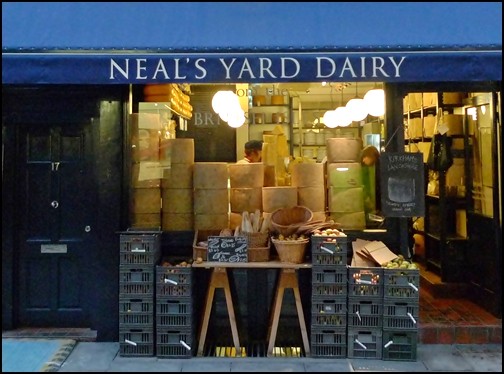

Behr takes himself seriously in the extreme, but he is an unusual mix of the thorough and slipshod. To address his subject, he traveled to England where he spoke with numerous people, including a food writer who organizes “Food Lovers’ Fairs,” a cheesemaker, a Cornish baker, a craft brewer, Heston Blumenthal (whom, “it may go without saying, is Britain’s most inventive chef” AoE 16) and several customers of his restaurant. These conversations follow no format or method; instead they are nearly random.

Behr takes pains to establish his bona fides. He is careful to mention that he knows Harold McGee and stayed with Tom Jaine (the publisher of Prospect Books and Petit Propos Culinaire) during his visit to England. In what sounds like a painful and implausible exchange with the Cornish baker, Behr confides that he

“promptly asked me if I knew Harold McGee, an American who is the best-known writer about the science of food (As it happens, I do know him.) And when I said I was staying with a friend in Devon, he asked if that were Tom Jaine. It wasn’t that [the baker] had had any contact with Jaine or McGee; he knew their names from reading.” (AoE 10)

This kind of passage ought to demonstrate an author’s willingness to poke fun at himself or his celebrity, but in this case is profoundly unironic.

Behr visited the Notting Hill farmers’ market and Borough Market in London, some dairies, the bakery and the brewery. He ate at Blumenthal’s Fat Duck, the Merchant House in Ludlow (the little town of restaurants with big ambitions and many Michelin stars) and a “well-regarded” but unnamed establishment in Lancashire that served him a soufflé with “the most bland sweet taste” he had “ever met [sic] in any restaurant with aspirations to quality.” In London, Behr dined at five restaurants: the Fox, Lindsay House (since closed), J. Sheeky (“Seats are not especially comfortable;” again unironic), St. John and The Square (an odd choice; it is formal French). Other than the dessert in Lancashire, Behr liked the food but did not seem to have much fun eating it; the business at hand was too serious for that. Incongruously, his reader gets no information about either the produce on sale in the markets or its quality; and except for the Fat Duck, discussion of the restaurants that the article identifies is relegated to abrupt endnotes. It is entirely cursory.

Behr has done some reading, but to describe it as ‘research’ would imply that he followed any systematic methodology. For example, he writes awkwardly of English sausages that they are “made tender with bread but not too much in good sausage--perhaps once a good sausage seldom had any.” (AoE 7) A cursory look at a butcher’s counter or reference to any number of authors would have provided Behr with a legitimate lawyer’s answer; it depends. Cumberland sausage is “the only traditional 100 per cent meat sausage of the British Isles.” (Reekie 28) Most of the rest traditionally include widely varying amounts of cereal, for flavor and texture rather than filler.

In addition to Colchester-Wemyss and Shand, Behr takes passing glances at Elizabeth David (of course), Dorothy Hartley, Florence White and others, but offers no real analysis and displays no understanding of their work: He only is dropping names.

The writing itself is weirdly primitive, like outsider art, when it is not merely weird (that in itself is surprising; according to the FT, Behr attended Phillips Exeter, but then so did Dan Brown; perhaps the academy is trying to develop a distinctive School of Bad Writing):

“The appreciation of eel is dying, though eel remains available and is famously prepared as jellied eel (once a favorite of Cockneys), the clear jelly containing parsley. Jellied eel is much maligned, but it can be very good.” (AoE 7)

Behr is deliberate, not to say ponderous; he seems like someone who chews his food slowly and for a long, long time. He can be thoughtful, but his thought process is strange. In discussing the Fat Duck, Behr muses that “[m]aybe also the English accept serious food more readily if it’s presented as a joke. Making one or two food jokes is fashionable in top Western restaurants, but Blumenthal uses jokes with abandon.” (AoE 19)

In discussing the wine lists in English restaurants, which in reality are not much different in format from those found in the United States, Behr muses:

In discussing the wine lists in English restaurants, which in reality are not much different in format from those found in the United States, Behr muses:

“Maybe moral disapproval explains the organization of wine lists in nearly all English restaurants. The wines are in ascending order of price, as if you selected first of all by that rather than by taste (the two having no direct relationship), or maybe to underline the cost of your sin. Food, happily, is listed in the conventional way.” (AoE 8)

This juxtaposition of the inane and the obvious is typical of “English Food” and it may not be without interest to other people. Digressing about roast pigeon in his loopy prose, Behr treats what seems painfully obvious as a revelation that food pedants probably will enjoy:

“Good old roasting, once typical treatment for a pigeon, gives a variety of delicious cooked qualities. To roast, strictly, is to cook a whole bird or a large piece of meat by intense radiant heat (if from a fire, then not over but before it because too much smoke would flavor the meat by the time it was done). A pigeon, for instance, acquires a richly browned exterior with crisp skin and luscious melting fat in contrast to the rare, tender, juicy interior accompanied by a range of other flavors, including those of the desirably well-done legs.” (AoE 17)

Whether or not anyone is dense enough to require this kind of description, the presentation of it makes the reader cringe on behalf of its author.

Behr is good on beer. He describes the brewing process, including the difference between top and bottom fermenting yeasts, the regional variations in English ales and the significance of the Real Ale movement, although the narrative characteristically includes iteration of the obvious and the unrelated (The brewer “worked in the company of his two dogs, a reminder of his earlier calling of shepherd;” this revelation too is rendered with the utmost gravity).

Behr is good on beer. He describes the brewing process, including the difference between top and bottom fermenting yeasts, the regional variations in English ales and the significance of the Real Ale movement, although the narrative characteristically includes iteration of the obvious and the unrelated (The brewer “worked in the company of his two dogs, a reminder of his earlier calling of shepherd;” this revelation too is rendered with the utmost gravity).

Elsewhere his logic is impenetrable. After noting the (debatable) view of cookbook author Peter Brears that English cooking declined after it became considered uncouth to discuss food in “polite society,” Behr adds that Brears “himself didn’t go so far as to suggest that the food in his book was in any way delicious.” (AoE 8) That non sequitur (one of many) precedes the casual comment that Jane Grigson “was largely Francophile.” Mrs. Grigson, however, wrote some ten books involving English food, including, aptly enough, the titles English Food and The Observer Guide to British Cookery, and strove above all to restore the reputation of her native foodways. As her daughter Sophie writes, “[s]he was chauvinistic about English food, but only in the most intelligent and unblinkered sense of the word.” (English Food x)

Beyond these lesser infelicities, “English Food” is flawed because Behr has chosen to accept the piñata of received wisdom about his subject. Behr declares, without citation, that “French haute cuisine descends from court cookery, but the highest English cookery came from private houses; it wasn’t public and showy.” (AoE 6) As Gilly Lehmann has demonstrated, however, “French court cookery was being widely imitated” in England during the 1600s, and while its significance gradually waned, vestiges of its influence remained discernable among the Quality into the eighteenth century. The food consumed in the upper reaches of society was not, however, coincident with French practice; by the end of the seventeenth century, “the ‘food hierarchy’ was different in England. Pies and puddings, for instance, fell outside the rules of French menu-planning.” (Lehmann 53)

English food was in fact ‘public and showy’ as well, until the return of a robustly native tradition during the eighteenth century: “[T]he idea of magnificence and display, so important in the cookery books of the early eighteenth century” lasted past mid-century. (Lehmann 374-75) Public dining remained socially important not only to reinforce the cultural bonds within social elites, but also in the festival feasts that grandees and the gentry served to their retainers, tenants and agricultural laborers. Internationally renowned taverns in London were places to see and be seen amongst an urban smart set. (Lehmann 373-74) English people did not hole up in their houses to eat in furtive isolation.

During this period, in an actual contrast to France, women became prominent as cookbook writers and professionals in the English kitchen. “Perhaps the most striking aspect, comparing England to other countries, notably France, is that authors and readers were often women.” (Lehmann 61) These facts are lost to Behr.

Behr also writes of the English that “[u]nlike the French, they don’t have a strong gastronomic tradition” (AoE 19) A cursory glance at any number of publications would have disabused him of this canard; for example, British Food, edited by Lizzie Boyd, runs to over five hundred dense pages and includes literally thousands of traditional and distinctive British recipes.

That's why the lady is a chef.

Once again, Lehmann’s research buttresses the observation; for example, by about 1750:

“The triumph of the women authors can be read as the triumph of the native English tradition…. The culinary style of the last third of the eighteenth century marks the reassertion of English tradition…. With Elizabeth Raffald and her followers…. English cookery was reinvigorated.” (Lehmann 286-87)

Despite the mythology recycled by many writers, that tradition never disappeared; “the history of good English food did not end cataclysmically with the outbreak of the Second World War.” (English Food x) The Editor can recall eating superb, even revelatory English dishes in Cheshire, Lincolnshire and elsewhere during the 1980s: roast chicken with bacon and bread sauce, stuffed chine, devilled kidneys, steak and kidney puddings, sherried marmalade trifle.

If there is a discernably English tradition, what is it? Somewhat inconsistently, Behr identifies one after all; it is plain to the point of banality. “In English cooking, perhaps even more than in French, meat overshadows vegetables, with fish falling in the middle. [Huh?] The cooking of all three is plain. Seasoning, apart from salt and pepper, is limited…. ” (AoE 6)

Once again, a little research would have gone a long way toward disabusing him of a common misperception. Back at any English butcher shop, Behr would have found those Cumberland sausages, and he would have found them seasoned with cayenne, nutmeg, rosemary, thyme and white pepper; their pedigree goes way back and they remain prevalent.

Behr’s oversight is all the more strange because he cites Elizabeth David, whom he credits with unearthing some historical if, in his mind, disused recipes during the 1970s. Behr does not identify David's particular work, but it began as a number of articles that appeared during the 1960s (not the 70s), mostly in the Spectator, but also in the Daily Telegraph, the Sunday Times (of London), British Vogue and elsewhere. These were assembled and published in 1970 under the title Spices, Salt and Aromatics in the English Kitchen along with some 50 pages of new copy on the raft of seasonings traditionally used in the English kitchen.

If the title itself is insufficient to make the point, David opens the book with this statement: “For some two thousand years, English cookery has been extremely spice conscious” and adds on the first page that “the English people have a natural taste for highly seasoned food” and “trade with the Near East and southern Europe brought us early in the evolution of our cookery considerable opportunities for indulging the taste….” (David 7)

Hannah Glasse, famously, included a recipe for curry in her 1747 bestseller and David catalogs the persistent use of herbs, seasonings and spices in English cookbooks and manuscripts written from the sixteenth through twentieth centuries. Kate Colquohon points out that “Glasse adored using nutmeg, mace and cloves, and for her sauces she reached for anchovies, horseradish, lemon, shallots, oysters and lots of cream” and highlights “the pugnacious bite of cayenne pepper, the taste of empire.” (Colquohon 209, 202) She explains that fish was “simmered in barely bubbling water or a court boullion of wine, stock and herbs and presented whole… sauced with mixtures of shrimp, oyster, anchovy and lobster and garnished with oysters, cockles, butter, wine or lemon.” (Colquohon 204) Other examples of robustly seasoned English dishes abound in the primary and secondary literature.

Nor is the Art of Eating particularly good in its rendition of English recipes. In offering his take on English fennel sauce, Behr notes that it is based on ‘English butter sauce.’ He actually is referring to ‘melted butter,’ the English version of Hollandaise thickened with flour rather than egg yolk and sometimes incorporating cream, but his recipe bears no resemblance to it. As Behr incongruously explains, he omits the flour and uses plain water to make--a French--beurre blanc. His recipe for a sauce piquante includes an introduction unaccountably fixated on whether to avoid processes requiring a strainer; strainers, however, do not seem to be in short supply and are not difficult to manipulate.

Based on “English Food,” the Art of Eating is an idiosyncratic but unreliable journal that reflects its creator’s unusual sensibility. That sensibility does not include any discernable sense of humor. Food and its flavors are addressed with solemnity but hardly with relish or delight. There is a nod toward historical research, but “English Food” contains less actual scholarship than meets the eye, and it is neither the author’s strength nor his real focus.

Based on “English Food,” the Art of Eating is an idiosyncratic but unreliable journal that reflects its creator’s unusual sensibility. That sensibility does not include any discernable sense of humor. Food and its flavors are addressed with solemnity but hardly with relish or delight. There is a nod toward historical research, but “English Food” contains less actual scholarship than meets the eye, and it is neither the author’s strength nor his real focus.

Apparently Behr is a bit of an autodidact, and the Art of Eating also reflects that fact, with the strengths and weaknesses that it implies; fresh insights counter a tendency to get historical questions terribly wrong. None of this, however, identifies the biggest problem we have with Behr’s periodical. The problem with the magazine is its insistence on taking itself so seriously: It sucks the fun out of food.

Gary Giddins has said of Louis Armstrong, as great a genius as we have had in any age or field, that he felt impelled to create great art but did not want his art to be ‘homework;’ it should engender joy. Reading “English Food” is like slogging through the homework assigned in an uncongenial course.

All of this may be unfair or misplaced: Squadrons of eminent chefs and bloggers may not be wrong in lionizing the Art of Eating. Perhaps the subject of English food, shrouded in so much cant, has simply defeated Behr as it has so many others.

Sources.

Edward Behr, “English Food,” the Art of Eating, no. 61 (July 2002)

Lizzie Boyd, ed., British Food (Woodstock, NY 1979)

Joshua Chaffin, “No artificial sweeteners,” Financial Times Weekend (10-11

January 2009)

Kate Colquohon, Taste: The Story of Britain Through its Cooking (New York 2007)

Elizabeth David, Salt, Spices and Aromatics in the English Kitchen (London 1970)

Hannah Glasse, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (London 1747)

Jane Grigson, English Food (London 1992); Introduction by Sophie Grigson;

The Observer Guide to British Cookery (London 1984)

Gilly Lehmann, The British Housewife: Cookery Books, Cooking and Society in Eighteenth Century Britain (Totnes, Devon 2003)

Jennie Reekie, British Charcuterie (London 1988)